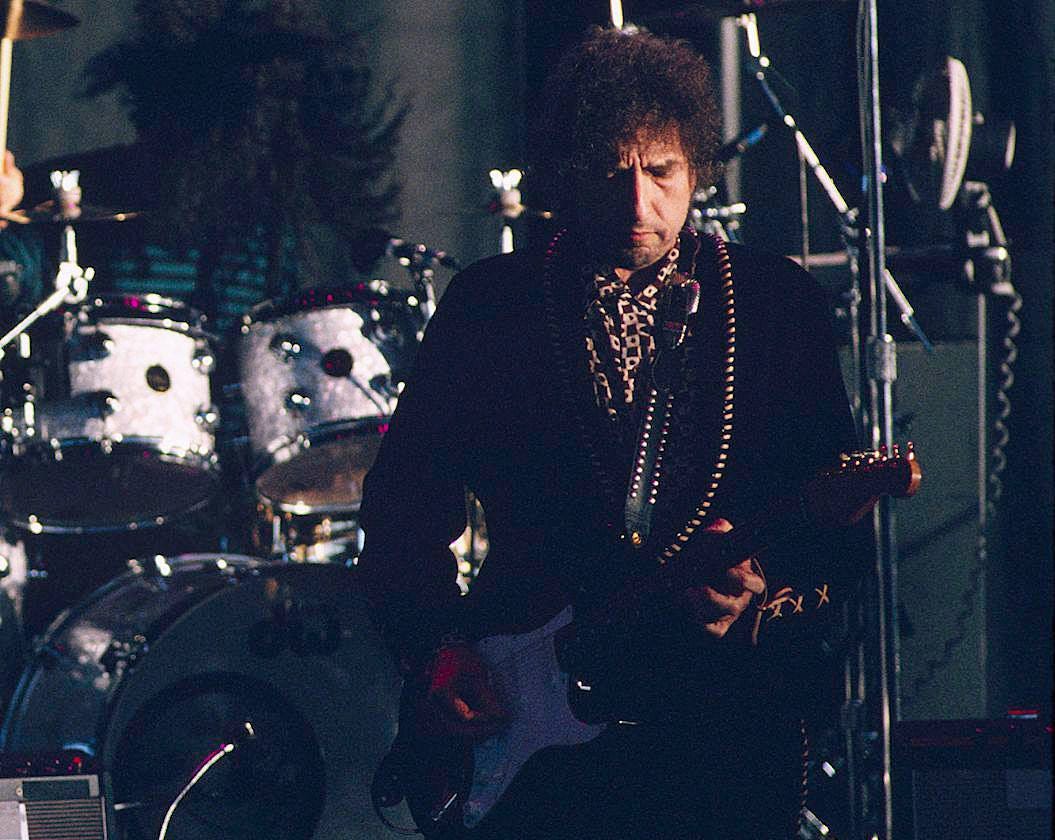

Winston Watson Talks Drumming for Bob Dylan in the '90s

"It was just the strangest of all gigs"

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Click the button below to get new entries delivered straight to your inbox. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only.

Update June 2023: This interview is included along with 40+ others in my new book ‘Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members.’ Buy it now in hardcover, paperback, or ebook here!

Winston Watson played drums for Bob Dylan during some of the best early years of the Never Ending Tour. He joined on extremely short notice in September 1992, filling in a second drum stool for a friend midway through a tour, before equally abruptly finding himself not only sticking around, but becoming Dylan’s sole drummer for almost four years.

Along the way, he played high-profile shows like Woodstock ‘94 and MTV Unplugged and behind all-star guests from Sheryl Crow to Van Morrison. He even found himself playing a bit part on Time Out of Mind, a year after he left the band. We recently hopped on the phone after his recent tour dates with the reconstituted MC5 for a long, discursive chat about all that and much more.

How’d you join the band?

I was in a little three-piece band in Los Angeles and working at a movie set company, doing a lot of side hustles because I had a two-year-old daughter. My best friend at the time, Charlie Quintana, was playing with Dylan. Charlie had played with him at the Letterman thing with The Plugz. I didn't know Charlie at the time that happened, in 1984. I would meet him three or four years later, and we became neighbors and best friends.

Charlie had invited me to the Pantages Theater in LA. They had a long run there, seven nights in '92. The first night, I went with my wife, and the phone kept ringing. Apparently my kid was raising the roof on Charlie's wife, so we had to leave the show and go home. So the next night, I came by myself.

I didn't know anything about Dylan. I had heard the songs everybody heard, and made fun of his voice just like anybody else. It just was not my thing at all. I was into Soundgarden and Alice in Chains.

At that Pantages show, I remember nobody really being happy and everybody drinking. Charlie and I got a bite after, and I remember saying to myself, "Man, you couldn't pay me to play in that band!" It just seemed like no one was having a good time.

I was living in Studio City at the time, and Charlie would keep in contact. One day a few months later, he called me and said, "Hey, what are you doing next week?" He asked me to fly out to Kansas City to play with them. I thought he was pulling my leg. I was like, "What does that mean? Like you and I? Because I know it's you and Ian Wallace [both on drums] right now." He says, "No, it's going to be you and Ian." "Oh, I don't even know the guy, man. What the fuck am I going to do?" "You'll be fine. There's not much left in the tour and I got to go play with Izzy Stradlin." I said okay.

I flew out to Kansas City. I had to pay for my own cab with the last bit of money that I had and made my way to the hotel. I went to the room, ordered room service, had a bath. I was just laying there in the tub going, "What the fuck am I doing here?" I was terrified. I had no idea what's going on.

One of the first people I saw was [tour manager] Victor Maymudes who was preoccupied with something, not really interested in talking to me. So I went out to the buses. [Driver] Tommy Masters says to Victor, "This is the kid that's coming out to play drums." Victor turned around and had the biggest smile on his face, and he's like, "Yes, we've been expecting you." At some point, the rest of the band gets on the bus. I'm trying to ask anybody I can get my hands on, "What's going on? How does this work?"

Before the show, are you given any instruction musically? "Learn these songs, do this, or—?"

No. At one point, they had a backline kit that I could check out, and I sat on it for a minute. I thought, "Isn't there another drummer here?" I didn't meet him until later. I thought, “I don't know what I'm going to do. I'll just try not to get in the way."

We get to the venue, and there's like 80,000 people there. It was like looking at the Grand Canyon, but of people. Albert King went on before us. When he finishes, we’re admonished to go on. I stepped up behind the kit. It felt basically like strapping on a rocket pack and going forward. There’s no going back. Tony just said, "Watch me, and watch him. It'll unveil itself to you."

Luckily, I had been there at Pantages checking out what they were doing. It was a lot of shuffles and stuff that I thought I could do, but I couldn't make heads or tails of the songs arrangement-wise. It didn't sound like anything that I'd ever heard before. I just knew that people seemed to know the songs when he started singing them, whether he sang them the way that they remembered or not. When the words finally come out, you got the hoots and hollers.

When you step on stage in Kansas City, have you even spoken to Bob?

No. Hadn't met the man. Hadn't said a word to him in my life.

Oh my God

It was just the strangest of all gigs. It seemed to be over before it started. I thought, "Wow, okay, that didn't hurt so much. It wasn't as terrifying as I thought." I had Ian there to be my guide basically. I just tried to duplicate what he did and stay out of the way. Any time he wanted to do a flourish, I tried to keep it down.

What was funny was, Bob knew that someone was coming out, but he didn't know I was coming out. You know what I mean? When he stepped up to the mic to sing, he hadn't turned around and looked at the band yet. At one point, he was singing, and then he slowly turned around to his left and looked back at me — and kept looking at me. There I was, like hair bigger than Angela Davis and my California Hurley gear on. Like in between verses and choruses for like two hours or however long we played. That was a little unnerving.

What are you thinking when you're getting those looks?

I don't know. [Rob] Stoner said something once about him shooting looks and I said, "Boy, do I know that." I just remember thinking, "Is this what it's going to be like the whole show, or is it just me?" Like I said, he was expecting someone, but I don't think he was expecting me. I had just barely turned 30 years old.

We finished the set, and he went off stage right. I thought, "Okay, I'm going home." The only thing I could think about was how the hell I was getting out of there and where my personal stuff was. Because I didn't bring any clothes. I just had an actual pilot's flight suit and some long underwear and shorts and an apple cap, like I was in Pearl Jam, which was the thing at the time.

Bob came up to me and said he liked the way I played and that he'd see me tomorrow. I was like, "What does that mean? Like, am I playing with him forever, or is he dropping me off at the airport tomorrow?"

I finally got a chance to call my wife, and she says, "Okay, so when are you coming home?" I said, "I don't know." I kept saying that for two weeks or however long the tour was.

Every night was something different. How can I describe it? All this gravity started to set in, because people were writing about it. I wasn't used to any of that. Not at least in that level. I've been in Circus and Kerrang! and all the rock magazines, but to be in USA Today? That took some getting used to. As you go back and research his history, there's no part of that that includes you. You have to step forward as if it's a minefield, and there are no footprints to guide you through.

I think all he ever wanted from me was to be myself. I immersed myself in older stuff, rootsier stuff, like Levon Helm or [Jim] Keltner, who I met before but never appreciated until I started really digging in and listening to those cuts. When I got rid of all the crap I had on stage and just pared it down to a four-piece kit, things were a lot better and more fun and not as tense.

Why did the smaller kit help you in that band?

I just thought it looked cooler. It didn't look so ridiculous, like a big Phil Collins kit. Ian had a pretty big kit, and I thought I had to compete with that, but I didn't. I was better on a Bonham-sized kit anyway. But I like two floor toms; Levon had one. The more I watched that kind of stuff and remembered what it was like to play in my mom's band, instead of being in a loud rock band, it was basically what turned the corner for me.

I’d grown up listening to country music from '55 to '76. When things started getting more pop, it's when I got off the bandwagon. Funny thing about my discography is there ain't much hip hop in there, but there's a lot of American stuff, like starting from past the Civil War up until now. That history with country music saved my butt in Bob's band.

I’m a rock player, period. I grew up playing rock and roll. That's what I am, and it’s where I move best, but I like to play a lot of other stuff too. When people call me to do singer-songwriter stuff, I try to summon guys like Keltner and Levon and Richie Hayward from Little Feat. Those guys have a certain thing that's quintessentially American. There's an unspoken swing. The more I learned about those cats, the more I learned about swing and not being so loud. Because I'm pretty loud. I play with the MC5 now. We're pretty loud, and a lot of that's my fault.

I've listened to the recordings, and you've got some songs to rock out on too. It wasn't all country stuff. You're doing “Watchtower” every night, going pretty hard.

Yeah, because he wanted to rock. Neil was out with Pearl Jam. Rock was the thing at that time. According to some of those cats that I talked to in management, it brought in a lot of the kids. The fact that we were rocking and rolling, that we could do Woodstock ’94 and Unplugged and all that stuff, that was speaking to a generation that hadn't even heard him, really.

Whatever contribution I made to that, I hope is cool. A lot of cats that I play with now who are younger, MTV Unplugged is when they first heard of me. It's like, "Wow, you’re the dude with the hair on the drums?"

Now everybody's got my hairdo 20 years after the fact. I was one of the only people who walked around with, not a tight afro like Rob Tyner, but it's like the big curly ‘fro, you know what I mean?

Yes, that thing was big. Didn’t it make you hot drumming?

No, it was like a giant heatsink. It actually drew stuff away, like how dogs have an upper and inner coat. But there were some nights we would play in places where it was heavy, like Louisiana or Alabama where there's a lot of humidity. It would not leave you alone. Tying it in a ponytail, getting by the air conditioner, even a bucket of cold water wasn't enough. I'm from Arizona, I know what the fucking heat is like, but the humidity they have in the South is just sick. It'd be like having a bear suit on while you play.

I used to complain about getting a ridiculous amount of camera time. I would always be behind him in still shots. I had to jeopardize my privacy. It’s bad enough that he has to have security. I don't need that kind of stuff.

And with the big hair, you're a recognizable figure. The other guys, some of them look a little generic.

Yes, and people think you're a certain way and they project stuff onto you. Then you don't fulfill that projection, and they're either hurt or sometimes worse.

What do you mean? What did people project onto you?

Like I'm Animal in the Muppet Show all the time, I'm not. I'm the polar opposite. I would like to go back to the hotel and watch TV or whatever. I haven't raised hell in a long time. Even when I did, it was in sensible shoes.

When people want to hang out, they want to drag you out to do nightlife stuff. Go to bars, introduce you to girls. You're nothing like they expect. Sometimes they understand, sometimes they're just offended.

I didn't know how to deal with that on such a large scale, because we toured a lot. I couldn’t make people understand that the interaction I’m having with them that night, it's a one-time deal for them, but I have to repeat it over and over and over and over again. Even though I don't feel like it, or I'm heartbroken, or homesick, or have food poisoning, or whatever. But it's not in me to be rude or aloof. Because I'm no different than anybody that comes to see us. I just got really lucky.

It was different than going out and contracting to play with someone like Sheryl Crow. You knew more about that stuff because it was contemporary but gosh, his stuff reached so far back. I didn't get a break to try to digest all his stuff for the first year or so. Even then, it didn't make any difference because none of his songs were like that anymore.

If you go back and listen to the records, that might not help you play the songs now.

Yeah. How do you play darts when someone keeps moving the board?

It's like Miles Davis. I don't think he gave a shit what you were going through the night before or tomorrow, he wanted whatever the fuck it was you had that night. I understand that, more now so than ever, mainly because of Bob and someone like Howe Gelb from Giant Sand. I had initially played with Howe in the '80s, which kind of prepared me for the unpredictability of Dylan in the '90s. The two of them, they were parallel. They’re very prolific, they're very idiosyncratic, and they're really special. They're the kind of people that come around every once in a while and you take note.

A lot of the purists thought I had no business being up there, and I can understand why. I go through the same thing with MC5 people. It's like, "You people realize I was five when that band first started, right? You realize I was three months old when Dylan's first record came out, so what the fuck am I supposed to know?" I didn't go looking for anything. I was asked by Dylan's people, and I was asked by [the MC5’s] Wayne Kramer himself to join, and I said yes. There are people who talk about it, and there are people who do. I'd rather hang out with people who do.

You said the only person whose opinion mattered was Bob's. How do you tell his opinion? Because when I've talked to other people, he's not someone who is going to give you detailed notes at the end of every show. He's a little inscrutable.

My wife kind of keyed in on something at the time. We called it the Charlie Chaplin thing. He would do this movement, like he's really feeling it. When that happened, I knew that “the Bob and Winnie Show,” as some of the fans were calling it, was happening.

He has this cool and innate sense of rhythm. If he likes something at 116 BPM, he'll always play it within a beat. If he says something's too quick, I'm not arguing. He said something's too slow, I'm not arguing.

So getting back to the early days, after that first two week tour, do you know that you're going to come back?

No. He and I sat down at a restaurant near Lafayette [the last tour stop] and had a conversation and smoked some cigarettes. I told him I had a blast. Because as terrifying it was, that knife’s edge of stage terror— I don’t need to fall out of an airplane or climb Everest to feel that. There's just nothing like it.

So then what happens after that next fall run? When the tour resumes in 1993, you’re now the only drummer. Ian’s gone.

Yeah. We went over to Ireland to rehearse at U2's place at the Factory. That's when all hell broke loose, basically.

Tell me.

[laughs, sighs, long pause]

If you want to…

Ian's gear was there, but he wasn't. I didn't know why. I remember getting into a panic.

You don't know going into these rehearsals that it's not gonna be two-drummer, like the last time?

No, I didn't. His stuff was still in the hallway, and I thought he was there. I thought, okay, I'm going to have to deal with him and fight for territory.

Bob had mentioned earlier that he wanted me to not be deterred. That I was here for a reason. Because I was intimidated at first. Then when I got used to it, he basically said that I wasn't going anywhere.

So I got to Ireland thinking that I was going to stand my ground, and, if Bob wanted it to feel a certain way, I was going do what I was asked. I walk in and all the backline’s set up, but it's only one drum kit. Mine. That's when I put two and two together. I remember going, "Okay, now it's up to me."

You get into a situation working with a bunch of working cats and they have a way of doing things, and you don't want to upset the herd. You want to fall in, and that didn't happen. Instead of me coming around to what they were doing, Bob played bass for a little bit with me playing drums. I remember thinking, "Jeez, he doesn't play bass. What's Tony going to do?"

He’s singing while playing bass?

No, just playing music for the most part, trying to get with my foot and my swing.

When you're doing these rehearsals, do they have a loose jam session feel, or is Bob dictating certain songs or ideas?

It started with a feel. We’d either build on that or it would go immediately into the trash. We'd have to retool, have dinner, and start something else. Drink and smoke a lot of cigarettes and get back to it.

I never thought I had to fill anyone's shoes. No one ever said, “Play like this or play like that." That is a relief, but it's also terrifying because it's all up to you to be intuitive. That's more intimidating than putting staff paper in front of me. Not being a great sight-reader, I can fake my way through a chart, but you can't fake your way through a vibe. People are like, "How can you memorize all this stuff?" I said, "Easy. You don’t play it like everybody remembers it. Just play it however he wants it today."

I will tell you, whatever came out on those early years, that was hammered out. Like all day. Fully catered, yes, I've had worse jobs, but it was a mindfuck that I wasn't prepared for. After the first night, I think we had two or three days, like all day rehearsals, just to get ready for that first show in Dublin.

That show was really important. Anybody who was famous and Irish and alive at the time was in that building. U2 was there because we're in their place all week, plus Carole King and Chrissie Hynde and Kris Kristofferson and Elvis Costello.

I can honestly say, on the last night we packed up rehearsal, he wasn't convinced we could do anything. He wasn’t happy until we started the first show at this venue across the street, the Point Depot. We lit the joint up and burned it down. Because there was nothing to lose. I played like a man being chased by wolves. They say, "one gig is worth ten rehearsals." Abso-fucking-lutely. It was ragged but glorious. There was nothing perfect about it. It wasn't like a Steely Dan song. It was rock and roll.

We then had that long run at the Hammersmith and worked out a lot of stuff there. John wasn’t GE Smith and I'm not Levon, but we weren't really aiming for that softer sound, as far as the rock part goes. Because he had that vignette in the middle where he would do the three acoustic songs. Like “Little Moses or “Boots of Spanish Leather” or “It’s Alright Ma.” So they’d do that, then I'd climb back on my kit and start making my little racket with “God Knows” or “Wicked Messenger.” The encores were fun too. It was usually “Rainy Day Women” or sometimes “Alabama Getaway” after we'd played with the Dead. That was always a riot to play.

He did a lot of stuff that I liked. We did a lot of stuff off of Oh Mercy and Blood on the Tracks and Blonde on Blonde. I didn't really know any of it, but my girlfriend after high school loved Bob Dylan. She would always put Desire on, and I would always want to throw it across the room. [laughs] She would put it on so much, and sing along to it out of key all the time, that eventually I started putting it on myself. It became a background to our romance. I think I even told Bob that story. I said, “If it wasn't for [Desire drummer] Howie Wyeth, I probably never would've listened to your music as much as I did.” Howie was tearing it up on that record.

You mentioned the quieter acoustic sections, what would you be doing during those when you weren’t playing?

When Bob plays acoustic guitar, I think it's the most beautiful thing someone could hear. Aside from Ry Cooder, I don't think I've ever met anybody do it better and sing at the same time. There was one time we were rehearsing part of the acoustic set. It was the first time I'd actually listened very closely to how they were doing “Hattie Carroll.” I was really moved by it, so much so that I didn't want to get back on my drums and play the rock part of the show. I wanted to hear more of that.

I told him that one night. I said, "I could sit there and listen to you play all night and not ever get on my drums." He says, "Do you think a room full of people would sit there and do that?" I said, "Don't give me that, man. Come on." I could talk to him like that, which was pretty cool. I was still a fan. I know you're not supposed to show that, but I couldn't help it.

He’s at best an interesting electric guitar player, but I love that too. It's impressionist for sure. He would say this nonsense about it being math—I think he plays what he wants to play. He’s a brilliant piano player, but as far as guitar playing goes, even after all this time, there's still a naivete about it. He knows what's involved, but there's still a bit of innocence there. You're not doing it for commerce reasons, you're doing it for purely artistic sake and not caring. He's not Eric Clapton, which is great. Neither am I. The part of me that plays guitar embraces that part of him so much. Even though it may not sound pretty in some places, it still speaks to me. Now, whether we come out on the other side together, that's something different.

He's a riot. I don't think he gets credit for it, but as serious as “Masters of War” is, he's a really funny guy. He and my daughter always got along because the both of them, they're just ridiculous together. I know grown women that would kill their own relatives just to be in a room with the guy. When my kid shows up, she's like, "Oh, hi Bob."

She would come along for some of the tours or some of the dates?

Yes. He would always run off with her somewhere, and they'd have their little talks. She was two to six when I was with Bob, and then she was nine when I was with Alice Cooper. She's been on a lot of stages and back stages a lot. To her, it's just another day at dad's workplace.

I'll tell you this one funny story about them in the Warfield Theatre in 1995. We were getting ready to do the show. I'm getting my clothes on. I see my wife in the green room, and I don't see my daughter. I said, "Deb where's Marcella?" She looks at me, the color drains from her face. She's like, "Isn't she with you?" I go into a panic. At one point, one of our guys sees me and I said, "I'm looking for my kid. Have you seen her?" They're like, "No, man, we'll help you look."

Everybody helped. At one point, I'd looked everywhere except Bob’s dressing room. I go up and knock on the door real quick. His assistant opens it or whatever and there she is.

We were already five minutes late going onstage, and the two of them were holding the show up. I said, "Babe, come on. Bob's got to go to work now." She says, 'Oh, okay." He says, "I want to talk a little more about that later, okay?" She's like, "Okay, Bob." And she grabs her drink and comes out and meets my wife.

At that point, I go to stand with the band and wait for him. They bring the house lights down. Bob stops me with his arm. He says, "We got to do something about that girl."

I said, "Oh man, I'm sorry, she just loves you. I didn't want her to disturb your show." He goes. "No, that girl in art class. She's real mean. We got to do something about her."

We’d gotten Marcella these cowboy boots and there was this mean little girl in her art class who splashed paint on them. Bob asked her, "How'd you get that paint on your cowboy boots?" So while I'm looking for my daughter, she's telling Bob that story, and they're holding the show up. He stops me and says, "Hey, we got to do something about that girl." [laughs]

Did you have a favorite run from all those years in the band?

I can't even tell you what my favorite run was, but I would say '94, '95. We were really moving those years. By the time we got there, the innocence was off. It was all business. We had something.

But just when you think you start to believe that, that's when he pulls the plug.

I knew it was coming, because we had this thing that we used to do every night and he wasn't doing that for a while. I felt like I was alone sometimes. I still enjoyed it but there was less of that interaction. I wasn't doing anything different…maybe that was the problem.

Your exit must have happened fast because I think it's only like six or seven months between that ’95 run you love and you leaving in summer of '96, after those couple shows around the Olympics in Atlanta.

Yeah. During the Olympics and all that stuff in '96, he wasn't happy. His manager was talking to the band about it. I said, “Man, I'm on the verge of a divorce, we haven’t played with each other in I-can’t-remember, I could go any time. Don't feel like you have to not say anything to me. I could get on a fucking plane right now and never look back.” I’d been there a good long time; I could understand.

So what happened was, I got a call from management. I said, "Okay, who'd you get?" They're like, “What?” I said, "Obviously, you're calling me either because you want me to come back out or you got somebody else. Who did you get?"

They said it was David Kemper. I said, "He's a great player. I think it’s what Bob’s aiming for now. We’ve been loud long enough." That's how I exited that play. I knew better not to stay in Mississippi a day too long.

On the DVD you did years ago, you also mention a time Van Morrison told Bob he should fire you. Was that around the same time?

That was part of it. It was at dinner. Van was visibly impaired and just blathering on about whatever. At one point I was mentioned and hung out to dry. I got up and unceremoniously put my napkin in my chair and walked out.

I almost didn't play that next day. I didn't care what anybody thought, and I didn't need anybody helping to put mines in front of me or trip me up. Especially not someone like that.

I didn't need anybody to tell me I suck. I only want to hear that from Bob, and he didn't tell me that.

You’re credited on “Dirt Road Blues,” but Time Out of Mind came out well after you left the band. What's the story there?

It was sort of a scratch idea I had done earlier. They had two guys in there, Keltner and Brian Blade, try to replicate what I did, and they couldn't do it. They couldn't duplicate the feeling, I guess, that was on mine. I called it a porch stomp. It's like you'd sit on a porch and hit spoons and stomp your foot. It was Keltner that said, "Well, why don't you just loop that? That's Winnie on there. Just loop that, and that's the song."

Was it like you were deliberately recording the song “Dirt Road Blues” and this is the part you came up with, or you were just recording a random drum track and that ended up getting used?

I don't know. I honestly don't know.

It's interesting that a little bit of drum that you played maybe several years earlier he’d remember, or that someone would dig out the file.

As I remember the story, either Lanois or Keltner himself said that they were working on that idea and Bob or somebody played the original thing, which was a cassette, from what I understand.

Mark Howard's book explains it. I think I have it here, hold on a second. Okay, here we go:

[Reading aloud:] “The song ‘Dirt Road Blues’ was created from a cassette tape Dylan had from a sound check. He asked me if we could use it, and so I made a loop of the best eight bars and the band played on top of it. Because it was a soundcheck recording, Daniel didn’t like it — he said the steel part sounded like the Bugs Bunny / Road Runner Hour. That’s why Winston Watson played drums on the album.”

So there you go. An offhand thing. I had no business playing on the record. At least that's my fragile ego saying that to me.

Well, it's one more studio recording than G.E and so many of the Never Ending Tour band members got up until that point.

Right. I'll take it.

Was there any sense in your era that his songwriting days might be behind him? He'd taken a fairly long break by the time you left, just doing the folk covers albums.

No. Not at all. Does the well ever dry up completely? I don't think someone with a fertile mind like his would ever do that.

Will he stop? Maybe at some point, but I think he needs to do it like anybody else, and he'll be the first person to tell you that. It's just something he does.

Watching him work was a lot to take in at that an apprentice age, when all the journeymen around you are questioning why you're even in the fucking room in the first place. One quote that I liked, which I agree with and disagree with in part, was that “it's interesting, but it's never fun.” I disagree. To me, it was interesting, and many times it was fun. Not all the time. It was serious business all the time, but you could have fun with it.

There were times, like I said, that were raucous enough to where we could grin at each other, all of us, where we did burn the barn down like the roadhouse band that we were. There was nothing really refined about any of it. We could have been that way, but not with me in the band.

That’s it for Part 1 of my conversation with Winston! In the second half, which will run in a few weeks, we talk about a dozen particularly notable shows from his tenure with Dylan: Woodstock ‘94, MTV Unplugged, playing “Restless Farewell” for Frank Sinatra, and more. Subscribe now to get Part 2 delivered straight to your inbox when it runs [Update: It’s here!]

1996-08-04, House Of Blues, Atlanta, GA

Update June 2023:

Buy my book Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members, containing this interview and dozens more, now!

I love this whole story but the part I won’t forget is Bob being worried about the mean girl in Winston’s daughter’s art class. Sooo great.

So entertaining, really enjoyed reading this.

Until this on-and-off series of interviews you've done of people who have played with Dylan, I'd never read so many accounts of what it's like. I had started to wonder if all these guys signed a pre-nup or something (as I've heard rumors of about Prince) - nobody seemed to give many details and anecdotes about playing with Bob.

So these are really valuable. Great stuff.