Tour Manager Richard Fernandez Talks Life on the Road with Bob Dylan and Tom Petty

1988-10-19, Radio City Music Hall, New York, NY

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan shows of yesteryear. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only. Subscribe here:

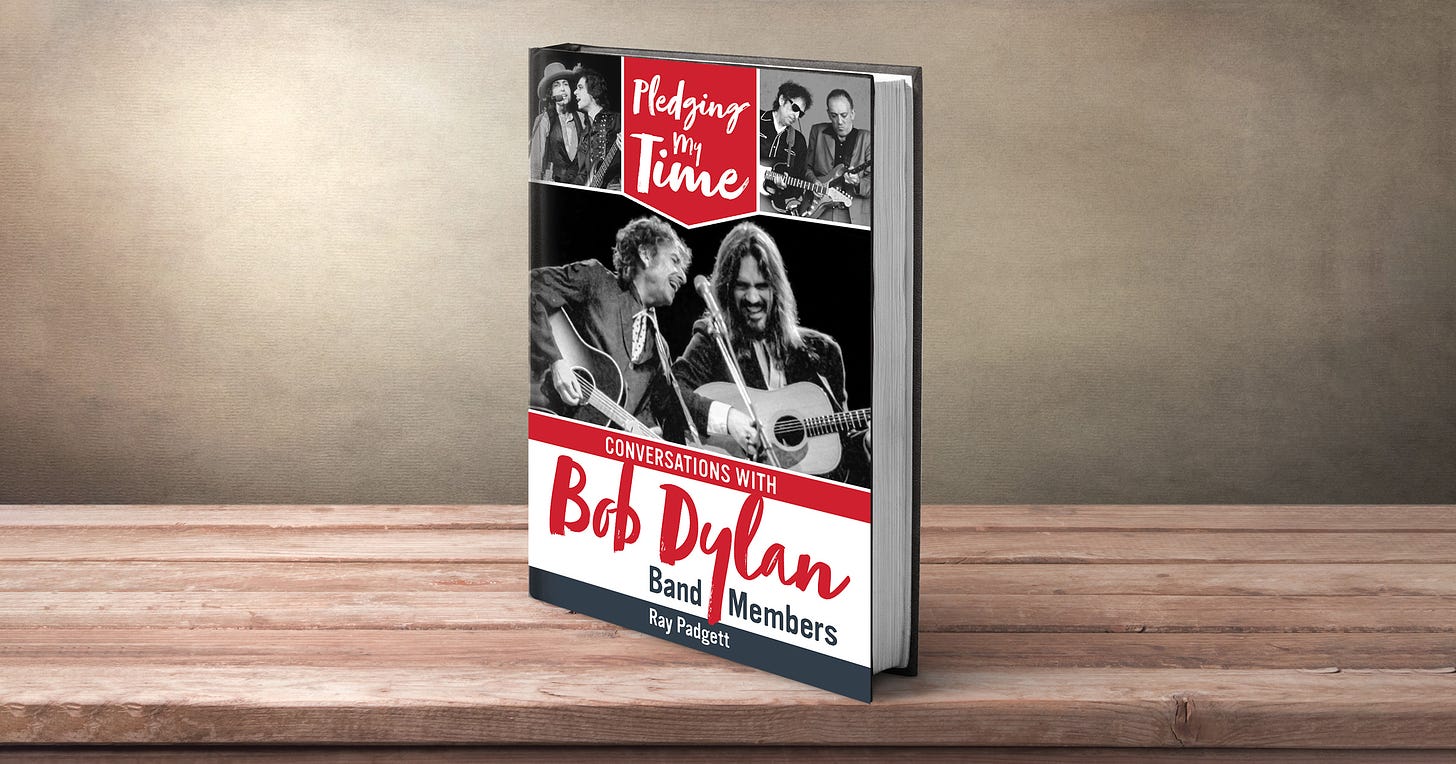

Update June 2023: This interview is included along with 40+ others in my new book ‘Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members.’ Buy it now in hardcover, paperback, or ebook!

In a career spanning five decades and counting, Richard Fernandez has served as tour manager for too many iconic artists to name. When he won the concert industry’s highest award in 2016, Graham Nash said, “When musicians are out on ‘the proud highway,’ we need all the help we can get. The secret is a good tour manager. For decades, Richard has been that lifesaver.” Ric Ocasek said, “There was chaos, but he was always calm and cool. He is good with people, and has a computer in his head. Of all the crews I ever worked with, he’s really the only one I remember!” And who should show up at the actual ceremony to present him with the award but Tom Petty, who Richard worked with from 1978 all the way until Petty’s death in 2017.

It was through Petty that Fernandez entered Bob Dylan’s orbit . He worked as tour manager when Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers backed Dylan in ‘86 and ‘87 and then, as Petty took a break from the road, continued on with Bob alone for the early years of the Never Ending Tour.

I called him up a couple months ago, as he was preparing to hit the road once more with Steely Dan, for a freewheelin’ conversation about his years with Dylan in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, Tom Petty, and what life looks like for a tour manager in general.

Was your first time working with Bob the first time he worked with Tom, at Farm Aid in ‘85?

Yes. Bob came to [his and Petty’s shared manager] Elliot Roberts and said he was going to do Farm Aid and he wondered if The Heartbreakers could work with him.

We were rehearsing up at Universal Studios. Bob would come to rehearsal and he'd only talk to Tom and the band, which was cool. Nobody talked to him or anything, but the rehearsals went down well. Bob would just come in and do his thing and then he'd leave. That's about it. But when we got to Farm Aid, and they actually performed it in front of people, it was pretty amazing. They played unbelievably together. I thought it was just going to be a one-time shot. Nobody knew what was going to happen after that.

Were the Heartbreakers and Tom jazzed about it after the show, do you remember?

Yes. That's the one thing about The Heartbreakers that I didn't know when I first joined up with them, but learned. They were so respectful to the people that came before them. I took Tom and Mike [Campbell] and Ben [Tench] to see Muddy Waters at a club in Phoenix one time. During his encore, his road manager came up to me and said, "Hey, do they want to come back and meet Muddy?" We went back, and they're in his dressing room. The door opens, and here's Muddy. He's coming off the stage. He's got a towel around his neck and he's all sweaty. He looks up and the first thing he goes, "Tom Petty. How are you?" Tom was like a little kid going, "Oh my god, he knows my fucking name!" They were like puppies.

That's one thing I liked about Tom and The Heartbreakers. They respected everybody that came before them. Playing with Steve Winwood was like, “oh my god!” That's what I really dug about them cats. That's the way they were about Bob.

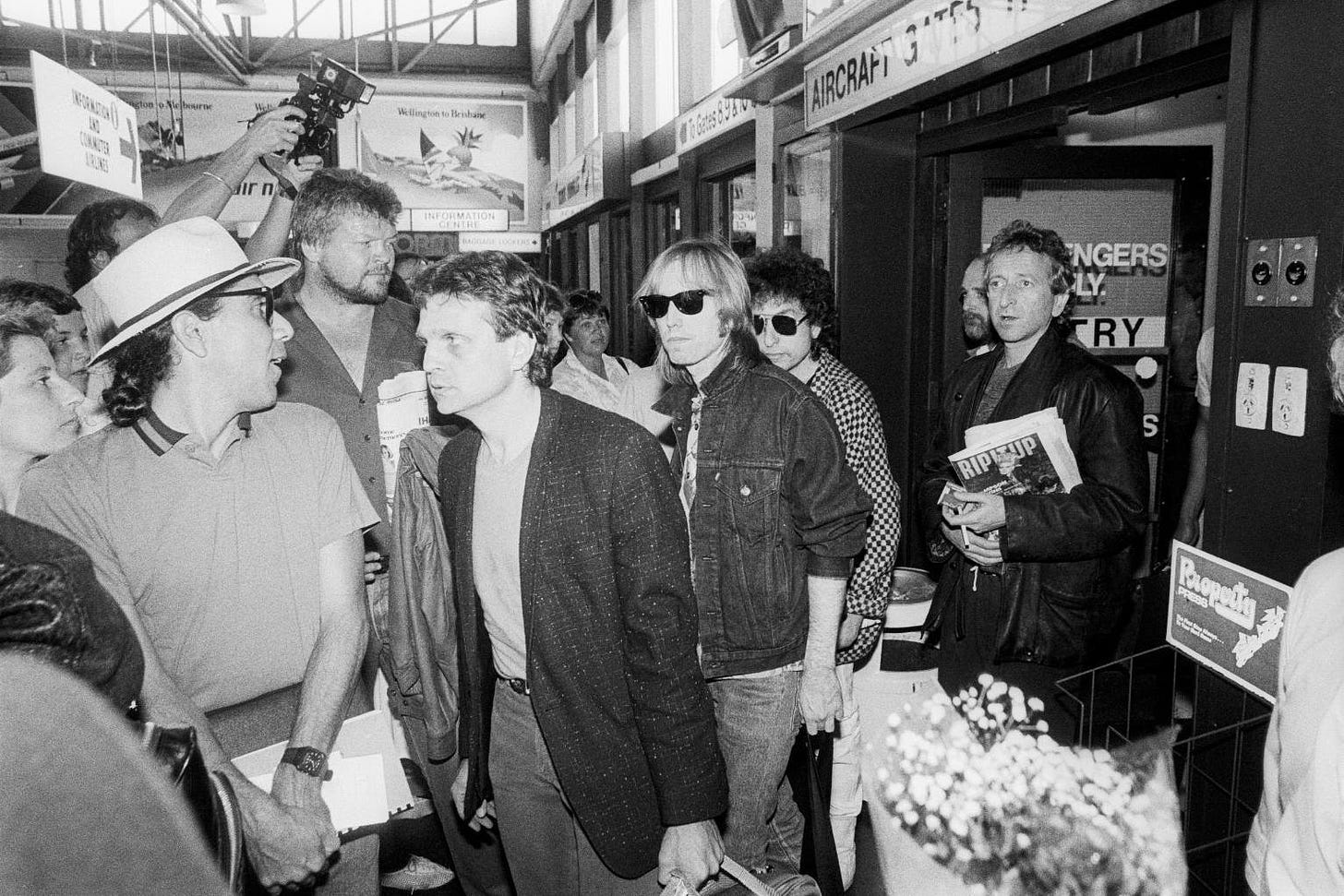

What is that first joint tour like, in Australia in ‘86?

I remember it going down very well over there. I remember promoters coming up to me and going, "Wow, this is the best band he's been with! He's actually doing the songs!"

“He's actually doing the songs”…

I mean, doing them in a way they recognized them.

The band, the Heartbreakers, they played together. Sometimes when [Bob] was singing, if he had his electric guitar, he'd be hitting the wrong chords and stuff like that. It never bothered The Heartbreakers, because they just stayed right there. “We got our rhythm section. We know where we're at.” Tom would go, "Here we are. Here we are." And [Bob would go,] "Oh. Yeah."

On that first tour, once we realized we were going to go do a tour in New Zealand and Australia, Bob would still just come to rehearsal, talk to maybe the band and nobody else, and leave. That was about it. Then we did a couple of shows.

We'd already had a few shows under our belt, we went to Sydney and it was one of the backup singers, Queen Esther Marrow's, birthday. I talked to one of the girls and said, "Listen, I'm going to set up a thing on the day off for the band and some of the crew guys. We'll set up at a restaurant, have a party for her. I'll get a cake." She said, “Oh, that'd be great. Let's not tell her.” I said, "Okay fine, don't tell her." I tell [Bob’s] manager [Jeff] Kramer. He goes, "Oh, that's a great idea." I get this restaurant, I set this party up, I sort transportation for the band and the crew to get over there and back.

I haven't even talked to Bob once yet, since before Farm Aid. I haven't spoken one word to him.

I'm sitting there in my room and it's about 11:30, something like that. We're not leaving until six. The phone rings. I pick it up, and he goes, "Hey Richard, it's Bob." I go, "Hey, hi, how are you doing?" The first thing in my mind, I pick up my itinerary, because I got a lot of new guys in the crew. I pick up my itinerary, I'm looking through going, "Bob fucking who?" He goes, "I was wondering what time the transportation is leaving for Queen Esther's party." I'm looking down, going, "Yeah, I think about six o'clock." [Suddenly] I realize, "Oh, fuck, it's Bob."

That was the first time I actually spoke to him. We'd already been through two full rehearsals and the Farm Aid thing, and that's the first time I actually spoke to him.

What would a typical show day look like on the road for you?

Well, it starts the night before. I printed out these sheets and stuck them underneath everybody's door. It says, today, you do this, this, this and this, soundcheck, whatever is happening. After the gig, this is what we're doing. Even though they have a book that says that, this gives them specific times if any changes have to happen. Tom liked it because he said in the mornings, he sees it, it's underneath his door, and he can look right over and go, "Okay, yes that's what I got going on." He leaves it there.

Then in the mornings, it's checking up, it's calling the venue. Let's say they load in at nine or ten o'clock. I'll call the venue about eleven and see how it's going. If there's any problems that have come up, if there's any problems that they foresee, whether they be technical, they can't get something in or out, or a logistical problem where there's some equipment that's [still] on its way. Just anything that might arise.

I want to know what's going on in the building, so when I talk to the artists when we get to the building, there are no surprises. Then once I've talked to building people, I start getting in touch with the people in my staff and say, "Okay, this is what we're doing today." Then check up on transportation, make sure it is going to be there when we go into the venue for the soundcheck.

I've been working with Steely Dan for many years now. Donald Fagen is a guy that does soundchecks every day, and I really respect him for it. I worked for Tom for 38 years. After the first 10 years, Tom never did a soundcheck. The only time we ever did a soundcheck is when we did the Super Bowl. He would just walk in the building, plug in the guitar. He paid everybody really good money, and he expected it to work.

That's one thing Tom cared about. He goes, "The lights are the lights, whatever, but don't ever try and save money on the sound.”

Was that what happened with the Dylan and Heartbreaker shows? The soundcheck was done by band or crew guys?

If we were doing multiple shows, Tom would go in there and do a soundcheck with the band out of respect for Bob. Even if Bob didn't show up. He just wanted Bob to know, "We're here for you. If you want to come down, let's go. You've got a full band ready to go if you want to work up something, or if you got a new tune you want to do." We were on Bob's clock. Tom understood that, and he wanted to make that apparent.

Would Bob show up much?

Oh yes, he would show up. I got a funny story about Bob at a later show. When I was working with the G.E. [Smith] band, for the whole tour, Bob wore gray sweatshirt, sunglasses, and a baseball hat. He came into every building that way. Sometimes he played on stage that way.

It was Halloween, and G.E. comes to me and he says, "Hey, I want to do something. I want to get the whole band and crew gray sweatshirts. I'm going to have them wear baseball hats and shades when he walks in the building." The band, the crew, everybody that was associated with us, the guy at the soundboard, the monitor guy. Gray sweatshirt, baseball hat, and shades.

We did the soundcheck, and Bob came up. He just looked. He didn't say nothing. Played the whole soundcheck, 20, 30 minutes. Put the guitar down. I'm leading him and his security guy to the dressing room. I opened the door, and he stops. He goes, "Hey, tell those guys I want my clothes back when this is over, huh?"

Hilarious.

I tell you, it's hysterical.

The other good thing that happened on the G.E. tour is, we were doing Radio City Music Hall for four or five nights [in 1988]. We had just played Philadelphia, and Bob was unhappy with the performance of the band in Philadelphia. He called my room the night we got into New York. It was unusual for him to call that late for anything. He goes, "I really didn't have a good time. It just wasn’t clicking." I said, "Okay, let me talk to G.E. We'll make sure they're down there for soundcheck as early as they can."

I call G.E. and G.E. goes, "Okay, we'll be at Radio City, and we'll make it happen." They got down there real early. Soundcheck usually doesn't start ‘til 4:30 or 5 because we had a eight o’clock show. They were down there at 3:00 going through everything. About four o'clock, Bob and his wardrobe lady and his security guy walk in the building.

I'm in the production office, and the production manager comes in and goes, "Bob just walked in. Oh man, he is on it." I go, "What do you mean?" He goes, "He's yelling at everybody he sees."

Then his wardrobe lady comes in. I said, "How's Bob?" She goes, "Oh, he's in a fucking surly mood. He's been screaming at me all morning. As soon as [security guard] Callaghan got there, he started yelling at Callaghan. He walked in, he yelled at Al [Santos, production manager] on the way up [to the dressing room]." I said, "Oh shit."

I call Callaghan, I says, "Callaghan, bring him down to rehearsals." [Dylan] goes out there. He's not saying much, but he's not yelling at the band. He just goes right back to his dressing room.

I go back to the production office, and I'm just sitting there. Suzi, his wardrobe lady, comes down. She says, "Bob wants to see you." I'm like, "Oh, fuck. Jesus Christ."

There’s one thing Tom Petty said when I got a lifetime achievement award a while back. He goes, "You know, the road manager is the toughest job on the whole thing, because if anything goes wrong, it's your fault." [laughs]

So I go, "Okay, just put your best game-face on, and do what you can do. Tell him you tried as hard as you can, and, I'm sorry dude."

He's gone to these long dressing rooms with mirrors on all over the side, for a chorus line or something, but he's the only person in there. As I opened the door, he's got his back to me. There's a mirror there. He's plucking away on a guitar. I didn't want to disturb him, so I opened [the door] and let it close very slowly. He sensed there was somebody there, and he looks in the mirror. He sees me. He turns around and looks at me and goes…"How about those fucking Dodgers?" [laughs]

The night before was a big night, the first night of the 1988 World Series where the Dodgers played the A's. Kirk [Gibson] goes in at the bottom of the ninth with two outs, they're down by one run, and hits a magic home-run. I'm a big Dodgers fan. I'm sitting in my room by myself watching the game, and when that happens, I just went nuts. I went yelling in my room, just hysterical.

[So at Radio City,] the door closes, he senses there's somebody there, and "How about those fucking Dodgers?" I say, "I couldn't fucking believe it!" He goes, "Yeah, what the fuck was that?"

Did he know you were a big fan?

We had been to baseball games together. We'd been to some minor league games where I didn't have to sneak him in. We also had been to Yankee Stadium.

The Yankees were really nice to us. We'd get three seats in a row, one of them on the end. We'd go to the Yankees office before the game and wait there. Then before the game started, I would go down and sit on the inside seat of the three, the one that was closest to the crowd. As soon as the bottom half of the first inning ended, Bob and Callaghan would walk down. Bob had his Bob Dylan uniform on, with the hood, the shades, the baseball hat, Levis, and just a ratty gray sweatshirt with no writing on it. Everybody was watching the game because it's the first inning and stuff. They would walk down and just sit right next to me. Bob would sit next to me and Callaghan would sit on the aisle.

We’d watch the whole game like that and talk baseball. He would notice stuff and go, "How come he did that?" I go, "Because that's a decoy. He wanted them to think…” He goes, “Oh, yeah yeah yeah.

You were like his baseball whisperer. You knew all the ins and outs.

Yeah, but he was pretty hip to the game. The other thing that we did on the G.E. tour is we would go to batting cages on days off, about five or six of us. Bob started coming. So he'd get in there and start hitting the ball. I go, "Dude, you have a batting stance like Rickey Henderson, holding it straight back." He goes, "I like him!"

It sounds like you didn't talk much early on. How did your relationship develop to the point where you're talking baseball at Yankees games?

Only because I never tried to initiate any conversation, other than if it was something business-wise - “we can't go on for five minutes because there's a guitar thing” or something like that. He understood that part of it, that’s why I was there. To make sure everybody is in the place where they're supposed to be with the right things. One time he called me a wrangler.

Being a tour manager, it's a fine dance because you're the guy that communicates with the management, the artist, and the crew. You're the guy that walks that whole line. You got to go to the manager and say, "We can't do this. We're changing this, and this, and this." Then you have things with the artist: “Rehearsals are doing this. Is this going to be okay for you?” And then the crew guys: "Oh, we need to get a guitar tech. Why don't you call what's-his-name in New York, see if he's available?" There's a lot of hats and a lot of people that I talked to.

It’s just a fine line that I have to walk, especially with Bob, because, at first, there was not a lot of communication. Then, all of a sudden, he realized that if he wanted something, if he let me know, it would get done.

Those early tours even with The Heartbreakers, they had so much respect for that cat, and continue to. I remember Tom telling me a story one time. I've always liked the song “Something Big,” but I never told Tom "you should play that song." I didn't want to be one of those cats. Then one day at rehearsal, he came and said, "Hey, let's do ‘Something Big.’”

I was stoked. I was talking to Tom, I said, "Hey, you’ve decided to do ‘Something Big’.” He goes, "Yeah, I was in the studio at home and I was deciding what songs am I going to play for this tour. I'm pulling up different stuff. All of a sudden, the buzzer rings, and I go to the gate.” He goes, “Yeah?” "It's Bob." They lived close to each other, down the road in Malibu. Bob came in, and said, "What are you doing?" [Tom] goes, "I'm trying to pick out some songs that I might do during the tour." Bob’s looking at what he had and goes, "How come you don't play ‘Something Big’? That's one of the best songs that you've ever wrote."

He pulled it up and he started playing it.

How did it happen that you transitioned to doing Dylan shows without The Heartbreakers?

Well, The Heartbreakers were not working. I never missed a Heartbreakers tour. They were working opposite each other for a while. There was one year where I did a Bob tour, I did Neil Young, I did Bob [again], and I did Tom. That was a crazy one.

Damn. And with Dylan, it's not like he was going out for two months a year and calling it quits. He was touring a lot.

Yes, we toured a lot. Tom was taking hiatuses too, recording albums, doing different stuff. He did Full Moon Fever on his own, just isolated.

Then in '91, I realized we were going to have a major [Petty] campaign in '92. I told Bob, I said, "You know what? I don't think I can be here next year. Tom's got a big thing going on. I'm going to be busy all year with that."

I wasn't sure what to expect, to be honest with you, but he was very gracious. He goes, "I understand. That's where you came from. You belong there with Tom."

Were you there before the G.E. band, when Bob was doing stuff with the Grateful Dead?

Yes. Bob played with them, I think, two or three different times [on the 1986 tour where Dylan was still backed by The Heartbreakers, before “Dylan & The Dead”]. I remember especially the time in Akron at the Rubber Bowl. That was the first time they played together. I remember me and Callaghan taking Bob over to their dressing room after his set, so they could work out what they were going to do on stage. It was like The Heartbreakers, nothing but respectful of Bob. "What do you want to do? Okay, we'll do it like that, then. Yes, that's cool. Okay, how about I do this there? No, no, no." It's like you could tell that they were digging it. They wanted to be up there with him.

It's the same vibe I got the first time walking into a building when Crosby, Stills, and Nash opened up for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. Me and Tom were walking into the building before they went on. We're walking by their dressing room, and David, Steven, and Graham were getting ready vocally. They were tuning up. Me and Tom were walking by. He goes, "Stop." He just listens for a second. He goes, "That is so cool."

There's only one cat that I can remember who was on the same plane as Bob when they would meet and talk. That's George Harrison. He respected Bob, but wasn't like in awe of him.

There were the shows Dylan & the Dead played the next year without Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers. Were you a part of the Dylan touring organization for those?

Yes. I was there.

They made a live album that Jerry Garcia later said Bob picked all their worst performances.

He thought a lot different than everybody else. His whole perspective on things was different from most people's perspective.

I remember, him and [Jeff] Kramer, his manager, were having a discussion. We were in Europe. Kramer wanted him to go on a bus somewhere. Bob didn't want that. He wanted to be in a car. I was walking by the office, and Bob called me. He goes, "Richard, come in here. Tell Kramer it's more comfortable for me to ride in a car than it is in a bus." So I’m like, "You know, Bob likes to ride in a car more than he likes to ride in a bus." Then Bob goes, “See?”

I never would question Bob, whatever he wanted to do. He's got his reasons. I don't know what they are, but he's got his reasons.

What do you typically do during a show? Are you able to actually watch any of it, or you running around backstage doing stuff?

That's the one time when I got 40 eyes watching the people that I've been watching. All these 40 eyes, the crew and the light guys and everybody, they're right there. They're making this thing happen. I'll go back to the production office, but I never missed Tom Petty [doing] “Wildflowers.” I never missed that song.

[But] if there was a problem, I was there. There was a time at the Outside Lands festival in San Francisco, where Tom was playing, and the PA was intermittently cutting in and out to the audience. The monitors were great, though, so Tom has no idea. He's having a fucking great time.

Sounds great to him, but bad to everyone else.

Yeah. I'm standing behind his amp looking at him. He's like, "What's going on?" I had to pull them off the stage. He goes, "Why? I can hear." I say, "The PA is cutting off in and out." I knew he was pissed off.

Steve Winwood was standing at the side of the stage. Before I walked up, I said, "Steve, stay right here. Don't go anywhere." Because I knew Tom would be really pissed off if he came off stage in the middle of performance. He goes off, and I lead right to where Steve is. Steve goes, "Hey, hi, Tom!" "Oh hey, hi, Steve. How're you doing?" Steve goes, "Yeah, that's okay. They'll get it fixed." Then he goes, "Yeah, I know." I was thinking, "Thank you, Steve."

Cheered him up. Smart, very clever.

The other person around who is good like that, and I've had around to help me out is Jackson Browne, who's a close friend of Tom's. I've had to pull Tom off when Jackson was around, and as soon as he sees Jackson, he just [cheers up].

Do you ever have to interrupt Bob on stage, pull him off for some emergency or other?

No, but I'll tell you something funny. At Madison Square Garden, if you go over curfew, they charge you like $5,000 a minute or some ridiculous amount. Me and Bob had talked about this beforehand. I said, "After 11:30 PM they're going to start charging you." He goes, "Okay, fine." He comes out for the encore. I said, "You got five minutes, dude, and then we're going into big time." He goes, "Okay. G.E., we're doing this but we're doing it really fast. We're only going to play like two minutes."

They only played like a minute or two into the song and then, boom, it's done. Bob walks up to the mic and goes. "I'd like to play more, but it costs too much."

Ha!

He's the same guy that, we were playing at the Greek Theatre in Hollywood, he's having a great time, they're kicking ass. He turns around to G.E. and he goes, "’My Way’, the way Frank Sinatra did it!" G.E.'s like, "Oh, okay…" [laughs] This is onstage! But they did it, and that's part of the genius. [Editor’s Note: Richard’s probably thinking of Sinatra’s “I'm in the Mood for Love,” debuted at the Greek in ‘88].

You mentioned Neil Young earlier. He was part of the band for the first few shows of the Never Ending Tour in '88. What do you remember about that?

He came to a couple of gigs. I'm not sure what happened. I don't think Neil wanted to do it. From what Elliot told Bob, Neil went down to Mexico on his boat or something.

Were there any other days or shows or events that jump out at you?

You know what always sticks out to me is the time that I played in East Berlin with Bob. We were on tour in Europe and [promoter] Barry Dickins called me up and said, "Hey, you've got a show here and you've got two days off and then you've got a show here. In between, we can do a show at East Berlin." I called up our production manager. I said, "Hey, can we do a festival in East Berlin?" He goes, "Yes, if we only pull out backline, and as long as they got some kind of lights, but if it's in the day, it really won't matter, what are they going to use for PA…” blah blah blah.

This is before the wall went down. This has been put on by the Communist Party, a free concert in the park. We get to the gig and there's 100,000 people. We’re just like, what the fuck? It was heads for miles.

I'm thinking, if the Communist Party put this on, they're trying to appease people. Why would they bring Bob Dylan here? He's singing all of his songs and these kids are just so into it. I went to the side of the stage, and am talking to this kid from Yugoslavia, all excited. "Oh, you work with Bob Dylan? As soon as we heard about it, we started driving to get here."

These are people that thought, "I never thought I'd ever see Bob Dylan." Just that alone to me was like, whoa, this is deep. This is way deep. They’re all singing their anthems back to him, and we are in a communist country.

I remember when the wall went down. We were on the road and I remember seeing Bob at the gig and he goes, "See what happened today?" I go, "Yes, I bet you one of the reasons is because of you, dude." He goes, "No, no, no." He would never take credit for anything.

Were you involved in the Grammy Awards when he played “Masters of War” in '91?

Yes. That's when he got the Lifetime Achievement thing or something. I remember we just came back from Europe. I remember Bob being up in his dressing room with Jack Nicholson and Yoko, then him coming down.

I think he gets uncomfortable and nervous accepting these kinds of things. He doesn't know how to really do it. I think it's something that makes him uncomfortable, to be the recipient of somebody putting you on a pedestal.

Both those guys, both Tom and Bob, I noticed they would get nervous at certain times. Tom would get nervous every time he walked on stage.

Really? Even after years?

After years. When we walked into the Super Bowl, it really freaked him out. Because at halftime, what happens is, the teams come in the tunnel, and we're walking out of the tunnel to go out to the stage. You're walking out of this tunnel, all of a sudden you've got 80,000 people yelling.

I'm walking on with the band. Tom is behind me. he's got his hand on my shoulder. We've got secret service guys. That's who they use for security, the secret service guys, because they don't fuck around. They talk nice and everything, but they know what the fuck is going on. I've got the secret service guy here, Tom's behind me, and he sees Tom’s hand on my shoulder. All of a sudden we get out to where there's people, and Tom puts both hands and he's like this on my shoulder [tightens grip].

[The secret service guy] looks back, and he can see that. He says, "Stop." He turns around and he looks right at Tom. He goes, "Tom, you're in the safest place you can be right now. We do this all the time. Nobody's going to get near you." I can tell Tom was thinking, "Okay. This is what I needed somebody to tell me." If I told him, I'm five foot seven and 140 pounds and I don't carry a gun. I'm like his pal. With this guy, he knew that this guy was here for us. "We're doing this now. Come on. Let's go." "Okay. Fine."

Both Tom and Bob would get nervous at certain times. Tom more so than Bob, but Bob had his moments where he would get skittish or afraid. I remember some threatening calls to Kramer's office when we were at Radio City Music Hall. Kramer had hired some extra security, the same kind of secret service guys. George [Harrison] was in Bob's dressing room, and I went up to get Bob because it was time to go on. Him and George, we walk into the elevator. George notices the guy at the elevator. George goes, "Bob, what's up with the suits?" Bob goes, "Oh, Kramer had some threatening calls and decided to call in some extra people." George goes, "Good move. Good move."

Was that generally stressful? Bob has some overly intense fans, you might say. I imagine there's a certain amount of nerves or tension. How was that for you to deal with?

Bob stayed in his rooms a lot. He'd go out for walks with Callaghan, but that would be very, very late at night. I took a couple of strolls with them late at night. We’d have to walk about 50 feet behind him.

One of the things that intrigued Bob was buskers. He would stand across the street and watch people. I think, in his mind, he goes, "I wish I could do that." He couldn't.

Those people probably never knew that Bob Dylan had been standing there.

Callaghan came to my room one time and said that him and Bob were out for a walk, and Bob had seen this busker and told Callaghan that he wanted him to open up the show. Callaghan went and got his number, and the guy goes, "Are you kidding me?" He goes, "No. Somebody's going to call you."

Callaghan gives me his number and says, "Hey, call this guy. Bob wants him to open up this show." I called the guy up. He didn't believe me. I said, "Why don't you come to the Sebel Townhouse here in Sydney? We're going to fly you with the band to--" I think it was Melbourne. I said, "We'll get you a hotel room. We'll fly you back the next day." He just couldn't believe it. He came to the townhouse and he goes, "This is really going to happen?" I go, "Yes, it's really going to happen, dude."

That's amazing.

I think in the back of his mind, [Bob] really digs that at some level. He was the most interesting cat I've ever worked with, let me tell you. Being a big jazz fan, I've seen a lot of video of Miles, and the way he handles rehearsals reminds me of Bob in the cryptic way they get things done. It's not really the normal way, but it's a little cryptic, how they get people or musicians to do what they want to do without really saying, "Play a G" or something like that. I found those similarities and it cracks me up.

I hope that Bob would find it a compliment to be compared to Miles. I always thought I wanted to work for a jazz band. I didn't really like a lot of rock and roll.

You got Steely Dan. For a rock band, they bring in more of that than some.

My father is a guy who turned me on to music and jazz and everything like that. When I did a Faces show at the Hollywood Bowl, my mom and dad came to the show. I remember after I got done, I went back and saw my pop. He goes, "Hey, that's a great blues band, you work for.” [Then] I had started working with the Eagles. He came to the show and said, "Oh, you're working for a cowboy band now." Then finally in '93, I guess this is the first Steely Dan tour after their hiatus, I brought my dad out to see one of the Steely Dan shows. He goes, "You're finally working for a jazz band."

Do you ever bring your dad to one of the Dylan shows?

I don't think so. He dug Bob. When I was listening to Bob at 16 and 17, my dad goes, "That's not bad." He was a jazz guy, but he was like, "Hey, that's okay."

Bob was, like I said, if not the most, at least the top two most interesting people I've ever worked with. I respect the hell out of him, let me tell you, to this day.

I felt really honored one time just because I was in town in LA, getting ready for something with Tom. Bob was doing a charity at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. It wasn't long after I'd left, maybe like three or four or five years after. Their production manager went, "Hey, come on down to rehearsal." Because I knew everybody. It's the same crew and everybody; I had hired a bunch of those guys.

I got there early and I'm standing at the mixing board with a mixer guy. Me and Eddie are talking and stuff, and Bob and the band walked on stage. Bob's looking around and goes, "Is that Richard out there? Get up here where you belong!"

One time I was on my way back from a Tom Petty tour. I used to have to go through Honolulu before they booked nonstops from LA into Lihue [Hawaii]. I was in Honolulu waiting for my connection to go back home. I see Sam, Bob's son, sit down. He goes, “Richard, what are you doing?" I say, "I'm going home. What are you doing?" He said, "Oh, I'm going to Lihue. I'm on my honeymoon." I went, "Congratulations. If you need anything, let me know. I'm there."

The next day [Sam] calls me. He goes, "I’d really like to go surfing." I said, "My next door neighbor has like 30 or 40 boards of all different sizes. Pick out what you want. I'll take it down there." I got a local beach about two miles down the road for me. We throw the boards in the back of the truck. Me and Sam go down there. We go out, we go surfing, and it was fun. We had a great time. He goes, "Hey, you know what, besides my wife, this made my vacation."

When I got up on stage, [Bob] shakes my hand. He shakes your hand like a gangster shakes your hand. They just put it out there and they don't grip back. Then, all of a sudden, I start to pull back and he holds it. I look at him and he goes, "I really want to thank you for taking care of Sam. He had a great time." I said, "No problem. Anything for your boy, dude."

It's funny that we have this relationship that's not a friendly relationship like, "Hey, Bob, what are you doing? What's going on tomorrow? What have you been eating?" But if we see each other it's like, "Hey, how's it going?" "Good. I'm glad." "How's your family." "Are your kids good?" "Great."

I remember him calling me the day after Tom passed, just to check in. He just wanted to call and say, "How are you doing?" He goes, "I know, it's tough, but we got to hang in there." I don't talk hardly any to him, but knowing that he called up and cared about a mutual friend that we both really loved…

Thanks to Richard for taking the time to chat! He he hosts a weekly jazz radio show Monday nights on Hawaii’s KCCR, which you can listen to online here. And if you want to learn more about his non-Dylan career, check out this great video:

Here’s one of the Radio City shows Richard mentioned, from 33 years ago today.

1988-10-19, Radio City Music Hall, New York, NY

PS. In a few days I'll run an interview with another behind-the-scenes person from the early days of the Never Ending Tour. This one will be exclusively for paid subscribers. Sign up here:

Update June 2023:

Buy my book Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members, containing this interview and dozens more, now!

A really interesting interview!

The photo is Wellington airport in New Zealand, not in Australia.