The Band's Role on Tour '74 (by Annie Burkhart)

1974-01-25, Tarrant County Convention Center Arena, Fort Worth, TX

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. We’re currently looking at every show on Dylan’s 1974 comeback tour with The Band. Half the installments are free, half are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

For today’s Tour ‘74 entry, tied to a one-show stop in Fort Worth, Texas, I wanted to do something a little different. Throughout this 50th-anniversary look back, I’ve been focused primarily on Bob Dylan. But, of course, this tour wasn’t just Bob Dylan. It was Bob Dylan and The Band. Billed that way on every ad, poster, and ticket stub. And, unlike when they last toured together in 1966, The Band were now stars in their own right. They played two sets each night of their own material, big hits that the audience likely knew just as well as they did Dylan’s songs.

By virtue of being a Dylan nerd I probably know more about The Band than the average person, but I know enough real Band experts to know I’m not one. So today, a special Band-focused look at Tour ‘74 by someone who is, Annie Burkhart. Burkhart is a Ph.D. candidate in English at the University of Iowa, an essential Twitter follow (her display name “jawbone annie” a nod to her favorite Band song), and a great regular guest on the podcast The Band: A History.

Below, Burkhart offers some historical context of where The Band was in 1974 (running on fumes—and other substances—only two years away from their Last Waltz breakup). She dives deep into the ten songs they were playing by themselves just about every night on this tour, where they come from and how they fit into the show’s narrative, and explores why Dylan knew he needed Rick Danko, Levon Helm, Garth Hudson, Richard Manuel, and Robbie Robertson for his big return to the stage.

So I’ll turn it over to her…

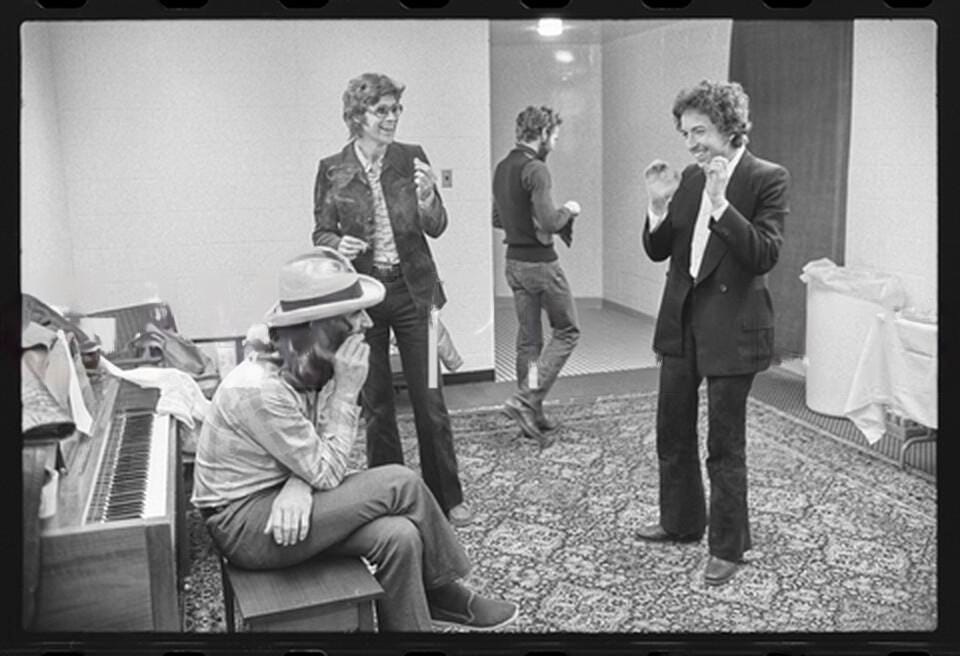

The Band seemed to be at once everywhere and nowhere in 1974. Drawing inspiration from the folky, Dylan-led vibe that soft-rocked the basement of Big Pink in 1967, The Band had spent over half a decade harnessing elements of rock, blues, jazz, gospel, and classical styles to blaze a trail now known as Americana. They noted the increasingly fast, self-conscious, and psychedelic sound of the 1960s and met it with a return to roots, invested, much like Dylan, in making music for themselves rather than a popular audience. Their first two albums are widely regarded as masterclasses in technical precision, and it seemed impossible that the group’s natural sympathy with this artistic medium could ever waver.

The Band’s success, however, seemed to change in time with the decades. 1970’s Stage Fright, primarily composed by an overstretched Robertson, was met with unprecedented negativity, the most memorable of which came from celebrated music critic Greil Marcus, who opined that The Band’s output was seeing a decline in creative spark and an increase in (self-) doubt, thus expressing a vague and distant lostness. Marcus set the standard for public opinion, and reception of the group’s 1971 record Cahoots seemed to be written on the wall. Around this time, The Band’s original compositions and public appearances declined dramatically. In recent decades, we’ve learned that Robertson and Hudson were in many ways carrying The Band on their backs until the group’s dissolution in 1976. It’s unclear whether this was evident to fans in that moment—or even if The Band themselves saw it as such. Music experts, however, were starting to notice. After a Toronto stop on Tour ’74, Billboard’s Jim Stephen observed that “organist/saxophonist Garth Hudson and guitarist Robbie Robertson do the bulk of the solo work and after one or two numbers it seemed as if one could actually hum the riffs along with them. Not that they were bad, just predictable.” However competent and talented Robertson and Hudson were in their own right, The Band were stellar because they were so much greater than the sum of their parts; they needed the whole five-piece ensemble to cook their magic. But watching Manuel, Helm, and Danko struggle to do more than go through the motions post-1970 is painful to witness. While Cahoots (1971) and Moondog Matinee (1973) have never gotten their proper due (hear me defend Moondog as a largely excellent covers album here), the group’s live double-album Rock of Ages (1972) manages to solidify its reputation as a top concert album of all time.

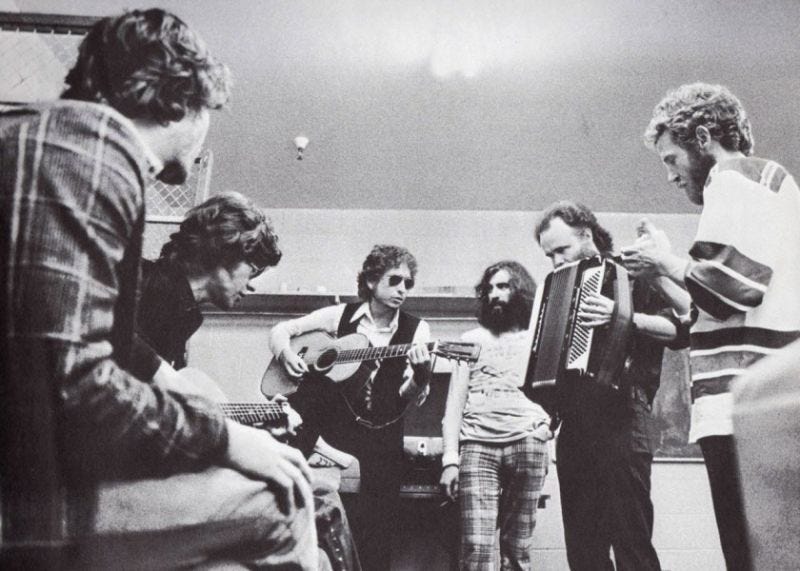

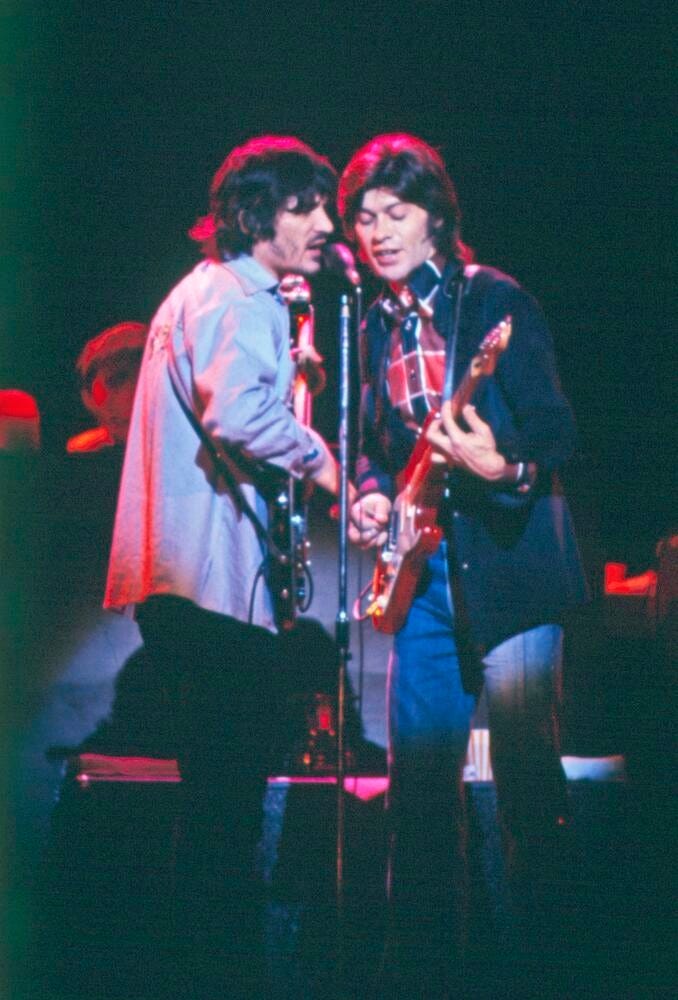

The group hit a proverbial wall between 1971 and ’72, and in some ways Tour ’74 may have been little more than a bid for survival. 1971 was widely regarded as The Band at their tightest, and they seemed to wish to remain in that year forever, to capture and preserve that magic. After all, The Band embodies a rare phenomenon: they tend to be better live than in the studio, and they excel when they have onstage immediacy. Robertson recalls their struggles with recording in isolation in Testimony, his 2016 memoir. In their early recording days, Robertson said to producer John Simon, “We have to see one another. We have to read each other’s signals. That’s how we play—to each other.” Indeed, in the small collection of live Band footage we have, knowing glances are exchanged between the five members; they speak each other’s language, and their cohesion relies on proximity.

What happens, then, when three members of the group don’t consistently show up, whether literally or figuratively? Not long before the Stage Fright sessions, The Band, like most of their contemporaries, fell into the clutches of substance abuse. These five musicians felt the weight of the world profoundly and struggled to cope. In order to stay afloat, they needed something to take the edge off. As such, Manuel—who was easily on par with Robertson with respect to songwriting skill, talent, and savvy—saw his composition credits drop substantially. To boot, Robertson was writing songs about Manuel’s demons, seen in “The Shape I’m In” and “Sleeping,” the latter a classic Manuel/Robertson cowrite. Manuel was not alone, however. Helm needed to be awoken daily from a near-comatose state on the studio couch in order to get Stage Fright tracked within an agreed-upon timeline, and Danko kept his classic “a little too drunk, a little too high” modus operandi through the ’70s. In the wake of these hurdles, the group stopped introducing new material into their live sets, as if clinging to their quasi-sober days, and more cars were crashed between Helm, Manuel, and Danko in the span of five years than many bands could claim in a lifetime. Manuel had to hang back during a live set due to punishing withdrawal symptoms. Robertson managed to keep working through a probable cocaine addiction, but perhaps only just. Hudson alone either kept his wildness and indiscretions away from the public eye or, more likely, avoided the throes of addiction altogether.

As these issues continued to mount, as Tour ‘74 arrives, The Band couldn’t “play to each other” in the way they did in their early years. Love was no longer a sufficient motivator, and, as such, they locked themselves into 1970. They included just two songs from Stage Fright in their Tour ’74 set (the title track and “The Shape I’m In”) and filled the rest with songs from their first two albums. Fans and critics alike expected more of The Band. Billboard’s Stephen noted that “[i]t’s puzzling . . . why the group, one of the tightest extant, chooses to ‘play safe’ when in concert and dedicate an entire evening to songs they performed in the early seventies.” This, indeed, seemed to be The Band’s moment of stagnant limbo, and Tour ’74 may have been the final puzzle piece behind Robertson’s eagerness to call it a day (or, in this case, a cool 16 years) in 1976. In a 1974 interview, Rolling Stone writer Ben Fong-Torres asked Robertson about The Band’s contract with Capitol Records—one that promised two more albums from the group—to which Robertson replied, “Umm… I’m not sure [what to say]. I think we have our hands full with other things. I’m not thinking about that too much, really. It’s not that interesting to think about. And it will just kind of take care of itself in the next few months.” Robertson is typically anything but vague, and these comments speak volumes by virtue of omission. A deliberate and methodical planner to boot, Robertson’s inability—or perhaps unwillingness—to speak to The Band’s next album, especially after three years without a single original tune, is telling. However, the idea that this powerhouse ensemble would cease to exist appeared to be too much to contemplate, and perhaps no one felt this more keenly than The Band themselves. Instead, the group stayed suspended in time as the seventies rolled on without them.

Bob Dylan, however, still saw a spark in his old backing band. If nothing else, Tour ’74 was an opportunity to redeem this once-booed act before tens of thousands of rock ‘n’ roll converts. The Band met Dylan’s confidence with a commitment to their hits. Each night, The Band mostly committed to the same 10 original songs, while also backing Dylan on 18 of his. The Band were realistically in no place to be playing a 28-song set each night, even at their prime, and 1974 was not the time to reinvent the wheel and set it on fire. Robertson, it seems, saw this as the group’s true test of fortitude. If they could withstand this punishing commitment, perhaps they wouldn’t need to call it quits prematurely with Capitol. (The Band did manage to fulfill their contract in the end, but only just. In 1975, they released Northern Lights-Southern Cross, which featured only eight tracks, and in 1977 they released the aptly named Islands, composed of B-sides from throughout their career that just didn’t jibe as a traditional album.)

The Band’s burnout, indeed, could hardly be more evident than it was during Tour ’74. Given our remarkable repository of recordings from this tour alone, it’s bizarre to hear which recordings made 1974’s Before the Flood, at least from a Band fan’s perspective. (The question of why Asylum greenlit these tracks for official release lingers in my mind. Especially given that ten different shows were professionally recorded for the album, couldn’t they have done The Band justice with this record?) Lead vocals from Helm, Danko, and Manuel, respectively, sound unusually rough for a group with three lead singers; there’s no place to hide within their tri-harmonic melodies—once strong and solid, now wavering, if only just. Every vocal miss is amplified in spite of (or perhaps by virtue of) being on the bill alongside Dylan, a man with a famously unconventional voice. Again, fans and critics alike expected more of The Band. Typically lauded for their precision and creativity, especially live, The Band had plateaued at best, sounding more rough than ready as they played almost 30 songs per night. The tens of thousands watching were prepared—if not eager—to criticize the artists who had helped Dylan forsake the folk circuit in favor of rock ‘n’ roll eight years earlier.

On January 25, 1974, Bob Dylan and The Band ended the first half of Tour ’74 at Tarrant County Convention Center in Fort Worth, Texas. The group had rocked—hard-rocked, this time—Memphis’s Mid-South Coliseum two nights before, shaking up their usually static set with “Goin’ Back to Memphis” before an elated audience. The Fort Worth stop preceded a day of double-shot performances (afternoon and evening) in Houston at the Hofheinz Pavilion. January 25 was in no way, however, a night that fans were any less excited about than usual. Just a few hours before the show, in fact, four fans were allegedly held at gunpoint by two men outside of the convention center. After hearing gunshots, the four handed over their tickets to the gunmen. Bob Dylan fans in 1974 would apparently kill to see their favorite—or at least threaten to.

After their minor deviation from their usual show in Memphis, The Band played the same tight ten-song set that they relied on from mid-January to February 1974—more or less a highlight reel of original songs released between 1968 and 1970. One of the two songs that came after the 1969 self-titled album, fan favorite “Stage Fright” featured a stunning Danko lead ostensibly about Robertson falling ill prior to their first show as The Band at Winterland Ballroom in 1969. In that February 1974 Rolling Stone interview, Robertson spoke to how the song resonated with their identity as performers and the ethos of The Band itself:

“Stage Fright” is, in fact, about ourselves. We’ve never been those kind of people—not outgoing, basically shy. We’ve never been very comfortable showing off. We play music, write songs and like to play them, but we have never and never will really have it in the palm of our hand. And we don’t want to. A lot of people I’ve gone to see, it just seems to roll off their tongue. They don’t seem to sweat. You see no pain in them whatsoever. It’s just a wonderful evening of entertainment. It’s not for us. It’s turmoil.

If we view the song as implicating The Band in their own struggle as showmen, it’s difficult to see this opening number as anything less than a calculated decision. The Band were not natural performers and went out of their way to remind us of this often. Their inherent discomfort is magnified tenfold when over half of the group’s members are feeling that sweat and pain so keenly both offstage and on.

As the six musicians close out the first Dylan set of the show with “Ballad of a Thin Man,” excitement mounts for Band fans. Fong-Torres notes a genuine dearth of Band performances between their Rock of Ages performance and Tour ’74: “They’ve done as little as possible, taking a year and a half between the recorded concert in New York, December 31, 1971, to a Watkins Glen performance in July, 1973. Then nothing until the Dylan tour.” The Band are nevertheless determined to wow from the get-go with “Stage Fright,” an unusually vulnerable number that typically appears much later in Band sets. The flustered lilt of Danko “suffering so much for what he did” entreats the audience to meet The Band where they are at this moment in time, to witness their struggle for identity and survival, both public and private. To extricate yourself from the shadow of Bob Dylan is not easy—and perhaps The Band didn’t want to. Maybe this moment of being both “caught in the spotlight” and retreating behind the shadow of something bigger than themselves was necessary to their survival. This raises a question: did it really serve them to be The Band in 1974? Maybe it didn’t—and maybe we can’t fault them for feeling that way. The song’s lingering tension—the push and pull between the desire to stop (the verses) and the need to keep going (the chorus)—reads as The Band unmasking before their Tour ’74 audience, a bid for honesty in the only way they could express it. It’s not just the president of the United States who must sometimes have to stand naked.

It's hard to say whether the remainder of the set speaks quite as clearly to The Band’s 1974 reality as their opening number did. This Fort Worth 1974 performance of the anthemic “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” reads as both practice and presage. Now Helm’s most celebrated vocal number, they were performing the song with the heart and feeling on this tour necessary to retire the song after The Last Waltz two years later. (Indeed, no configuration of The Band played this song at any point after 1976. There is endless speculation as to why—ranging from worries from Helm about being regarded as a confederate sympathizer to a disdain for Joan Baez’s successful pop arrangement of the tune.) While the group served nothing less than their usual cocktail of groovy funk and technical precision in their performance of “King Harvest (Has Surely Come),” their arrangement of “When You Awake”—rock-ified and forsaking the folky, outside-of-time spirit of the song—betrays a hint of anxiety, an inability to slow down. Manuel hits the falsetto tones of “I Shall Be Released” with more force and urgency than ever, his warbling vibrato almost begging “every man who put [them] here” to release them from the pressure of being The Band. Danko, Helm, and Manuel all but yell “any day now” in pitch-perfect unison as if that day could not come soon enough. Whatever financial, artistic, and spiritual sustenance they derived from music seems irrelevant in this moment of connection to something much greater. All is just as soon forgotten, however, when The Band transport us to backroads America in “Up on Cripple Creek,” The Band’s all-time highest charting song.

After another Dylan set, bookended by “All Along the Watchtower” and “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” The Band shake things up with veritable bop and chart climber “Rag Mama Rag.” This ragtime tune features Hudson on keys, Danko on fiddle, Manuel on drums, and Helm on mandolin, with only Robertson staying faithful to his native instrument. Moving next to “This Wheel’s on Fire,” a haunting and slightly sinister Danko/Dylan cowrite, The Band—albeit via Dylan’s poetic persona—put the frivolous fun of ragging behind them, demanding that we “notify their next of kin.” Whether figuratively, biblically, or literally, the end is most certainly nigh—and this comes to the fore in full force on the next number. Robertson claims to have written “The Shape I’m In” for Manuel, and it’s certainly an explanation that, while it makes perfect sense, portends a bit too much. You don’t need a PhD in literary studies to identify “save your neck or save your brother / looks like it’s one or the other” as too close to the bone within the context of Band lore. In Martin Scorsese’s 1978 concert film The Last Waltz, Robertson noted that The Band had been playing together in some form for 16 years and that he “couldn’t even discuss” 20 years on the road. Robertson supporters typically link The Band’s breakup to this moment, celebrating Robbie for identifying the point at which Manuel, Helm, and Danko needed to step back and take a chance at sobriety. Robertson detractors, on the other hand, take Helm for his word in memoir This Wheel’s on Fire, in which Helm accuses Robertson of making off with the lion’s share of Band royalties as a result of an unfair division in songwriting credits. In this spirit, Helm blamed Robertson for Manuel’s suicide, making the (dubious) claim that Manuel would not have contemplated suicide if not for Robertson’s actions. Regardless of where any of us as Band fans land within a dispute that continues to rage within the fandom, “The Shape I’m In” gestures toward a future more bleak than most Band partisans, in hindsight, can stomach.

No song could be more effective as a palate cleanser and closing number, then, than The Band’s most known and covered song, “The Weight.” Exhaustive scholarship on this number gives us an endless highway of interpretive avenues to follow, particularly lyrically, but as comfortable and commonplace the song may feel to fair-weather Band fans, the most profound meaning comes from acknowledging it as Harold Bloom does—as a song that “doesn’t quite know itself.” Indeed, we might read it most fruitfully as music writer George Plasketes does—as an “enduring, expanding, eminent mythology.” “The Weight,” for Band devotees especially, serves a recognition of our being always yet never home, keeping us—and, more important, The Band—perpetually within a Lacanian uncanny, at once nostalgic and foreign. In this spirit, The Band were indeed everywhere and nowhere in 1974, and they close their Fort Worth set reiterating the perks of being caught in the spotlight; in the shadow of Dylan; and in the infinite daydream of Americana.

Thanks to Annie Burkhart for today’s guest entry! Follow her on Twitter and her website.

1974-01-25, Tarrant County Convention Center Arena, Fort Worth, TX

Previously on Tour ‘74 (or click here for the full series):

Stories in the Press: Memphis 1974

Newspapers.com happens to have good archives of two Memphis papers, the Commercial Appeal and the Press, so there was a lot to check out about today’s one-off at the Mid-South Coliseum. We’ll go in chronological order, from the previews a few months out through the post-game coverage in the days and weeks after.

In the Ann Arbor show and on BTF, The Band played "Endless Highway". We never heard it before. After the show we were all asking each other, "what was that song.", because it blew us away.

I saw the Valentines show, 74, LA Forum and dug it a lot...I must say,personally, I think Northern Lights/Southern Cross is an excellent LP, then again often music appreciation has to do with how one associates the music with his personal life at the time, sure, but still....I think the LP is a fine effort...the entire album