Rolling Thunder Roadie Rich Nesin Talks 'Desire' Sessions and Breaking Bob Dylan's Guitar

Plus his later stints on the road with Dylan in the '80s and '90s

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

Rich Nesin has spent a lifetime in the touring business, working in various behind-the-scenes jobs for artists like Blue Oyster Cult, The Dictators, and Jim Carroll. But his very first tour gig was as a roadie for Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue. At only 24 years old, he stumbled into the gig through his work at the New York rehearsal studio the Revue booked to get ready for the tour. He ended up on the road with that motley crew all fall.

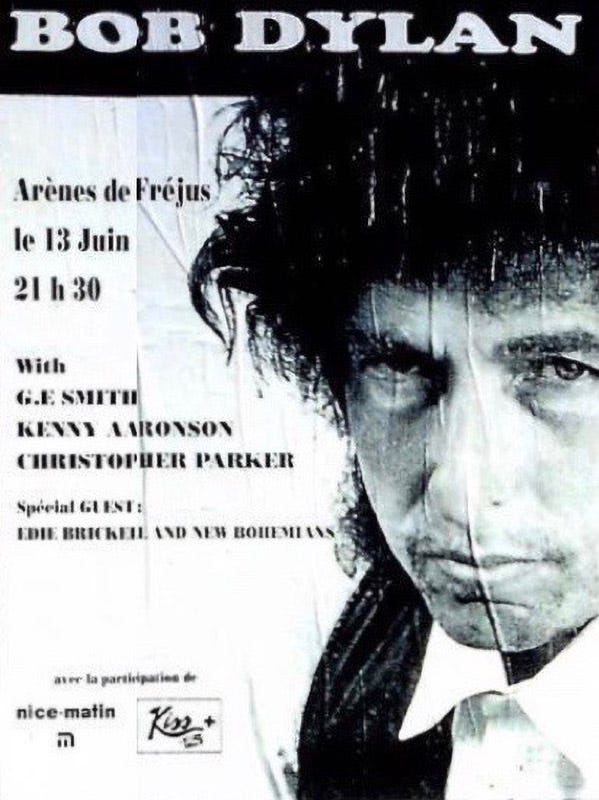

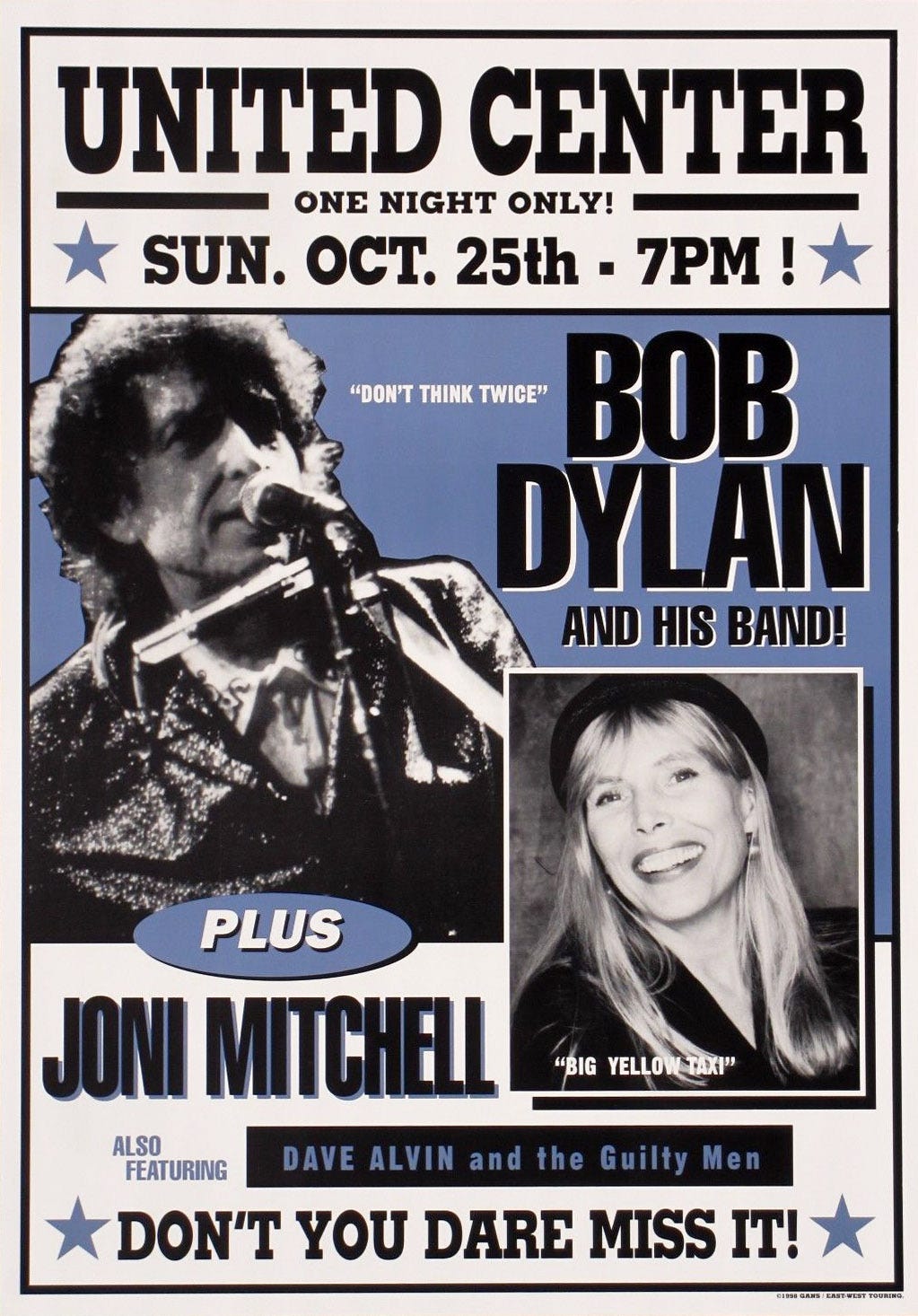

Then, over a decade later, Nesin found himself back on the road with Dylan again—and again—and again. He tour-managed three separate opening acts in the ‘80s and ‘90s: Steve Forbert (1988), Edie Brickell and New Bohemians (1989), and Dave Alvin (1998). Then, even after all that, he worked on select Dylan shows into the 2000s as production manager and promoter rep at various venues in the Northeast.

Below, Rich shares his stories of working on Dylan tours during three different decades, from eating shrimp cocktail while Dylan and Clapton recorded Desire to the time he accidentally broke Bob’s guitar onstage.

How did you first encounter Dylan?

I graduated college in 1974, and, by mid '75, I was working in Manhattan at a rehearsal/rental studio called Studio Instrument Rentals, known in the business as S.I.R.

S.I.R. comes up again and again when people tell me about Dylan, but I only vaguely know what it is. You seem to be the guy to ask.

S.I.R. began in the late '60s, early '70s, as a rental operation for recording studios. Then they built some rehearsal studios within, and it became a multi-faceted place open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week—originally in New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and then for a short time Chicago. Now they're all over the place.

They were serving the interests of studio musicians and recording studios, and bands that would go on the road and needed to rehearse or take stuff. They just molded it all into one place.

So not a recording studio itself, correct?

It is not. They are strictly a service industry. Rentals, rehearsal space. They're still going strong. They're all over the country now.

As a delivery person for them, I was always being tasked to go places. I sat in on sessions for Gaucho with Steely Dan. If Donald and Walter needed something: "Okay, call up S.I.R." Within two hours it would be in the studio. And sometimes they wanted the person to stay, because I would be the one moving it around, or they only needed it for a short while. That's how it kind of functioned.

So that's how you ended up at the first few Desire sessions?

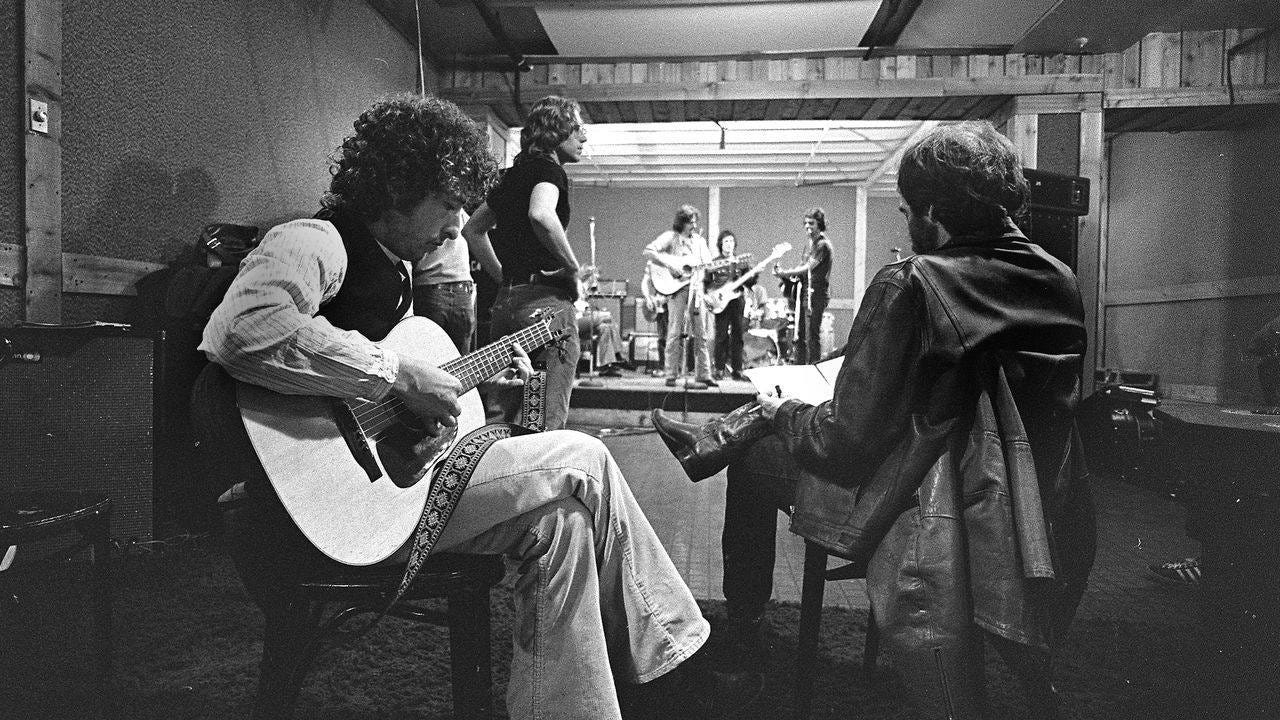

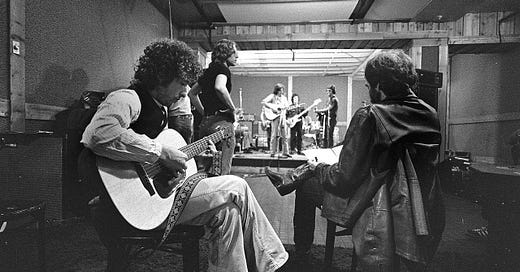

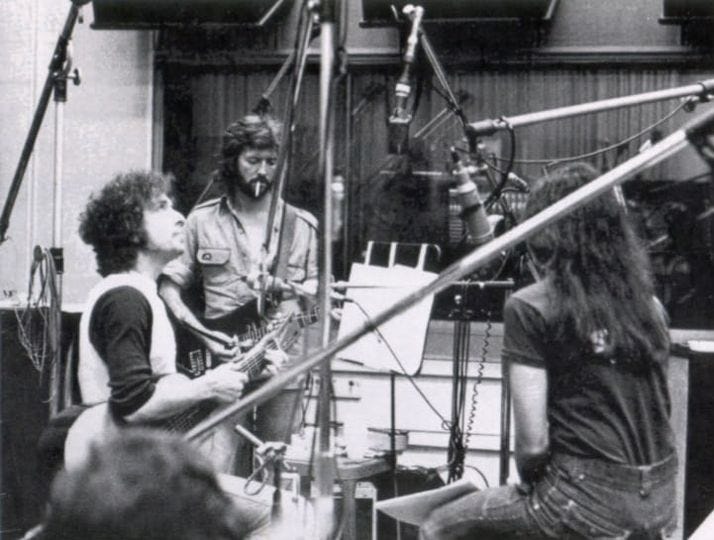

This is July of '75. What happened was, there was a show in Central Park by an English band called Kokomo, who had been born out of the ashes of Joe Cocker's old Grease Band. They got a call to come play on this Dylan session. We had rented them some gear, so I was at Central Park with them that evening, and then I had to take that gear and an additional amount of equipment over to CBS Studios on 52nd Street. The rental over at the CBS was a two-night rental. Because it was that much equipment, I had to stay there.

The first night was really a wild night. That's the night that—I mean, it's been written about a bunch—a lot of people were there. Eric Clapton was there, Emmylou Harris, many of the people who became part of Rolling Thunder. And I just sat in an anteroom that had a nice big spread of fresh shrimp cocktail. I stayed there till about four or five in the morning, maybe even later when it broke up, and then I was dismissed. The gear stayed because they were coming back the next night. So I had to come back the next evening as well. And that was my first encounter with Bob Dylan.

Are you doing anything during the session, or you're just there as the gear’s minder?

I'm just there in case they needed to move a piece of equipment or in case they wanted something different. Just like any other studio technician, but I was representing this equipment specifically.

What was your read on the sessions? The story is that there were way too many people early on; Bob eventually sent most of them packing.

You've got to understand, at that moment in time, I'm a 24-year-old kid, pretty fresh out of college. I had a brother who was almost six years older than I am, and The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan was a staple in our house. So I grew up listening to this stuff, and then to be thrust into the situation where I'm literally 30 feet from the guy, I was a wide-eyed, slack-jawed kid. I just couldn't believe I was there. But I had zero interaction with him those evenings. I didn't speak to him. Other than seeing him passing, I didn't have any contact with him at that point.

Now, you fast forward a few months. I'm still working for S.I.R. One Saturday night, I was the guy on call. I was actually at CBGB's that night. I got done about three in the morning.

Do you remember what show?

Maybe early Mink DeVille or City Lights, a pretty obscure band. I wasn't there on behalf of S.I.R., I know that. But as the person on call, I always had to go back to the studio at some point to check messages. So I get back there like 3, 3:30 in the morning. There's a message that I need to pick these two people up at JFK at seven o'clock in the morning coming in on a red-eye. The message was extremely explicit: Stay with them, do anything they want, take care of whatever it is they need. Be their guy.

It turns out the two people coming in were Barry Imhoff, who was the organizer of Rolling Thunder, and a second person. It might've been someone as high up as Jacques Levy or Louie Kemp.

They had a bunch of stuff they were taking to a place on Park Avenue. I had the van, they piled in there with the gear, and I took this stuff to Park Avenue and dropped it off. Then they were hungry, so I took them to a coffee shop on 28th Street and 6th Avenue called the Vandar Coffee Shop, which is long gone. It was a kind on unique place because it opened up at three o'clock in the morning to serve the Flower District folks, and then closed around 11 a.m. when all the flowers were out of the area. It's a McDonald's now.

They loved it and had a great breakfast, then I dropped them at their hotel, and I went my separate way. I still had no idea what this was all about.

The next afternoon, they came in for a meeting with my bosses. I got called in. "Here's what's going on: We have this project we're bringing in and it's top secret. But you really were wonderful to us. We want you to be our liaison with S.I.R. We don't want everybody walking in and out of the studio. Whatever we need, we'll go through you."

I said, "Okay, fine." I still didn't know who the artist was. Nobody had heard the words "Rolling Thunder Revue."

The next day, I was supposed to be there at like 1:30 or 2 in the afternoon. I'm in the studio with all the prescribed equipment that they wanted. Eventually, folks walk in. One of them was Bob Dylan.

That first day, it was just Bob, Rob Stoner, Jacques Levy, myself, and maybe some of the guys on the film crew. It was very sparse. They proceeded to work until almost midnight. I sat at the back of that room, and they sat on the stage with a piano and a guitar and went through every song he had written, including “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.” I mean, I got to sit in the room and listen to him sing “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” to an audience of like three!

Keep in mind that I'm a novice as a roadie. I'm just a fan at that point. I had no idea where this was taking me.

Are you having any interaction with them? Are they asking you for anything?

Not really. Bob might say something to Rob Stoner. Rob would point to me and say, "Hey, can you move that over to here?" It was indirect communication.

So that's the first day of rehearsals. Then the second day, everybody starts to come in, the people who were going to be part of this thing. Then, before the start of the third day, I got asked to come down to Barry's office. That's when he explained to me what was going on.

But amongst the explanations of how much I was going to get paid—or rather how little I was going to get paid—what my per diem would be—I had no idea what per diem was at that point— he had a couple of codicils to the whole project, which was, “Bob Dylan is not your friend. He's not going to be your friend. He's not looking to become your friend.”

Again, I can't emphasize this enough, I’m a wild-eyed young kid with stars in his eyes. “Okay, I won't talk to him, whatever you say.” I really was completely naive. I didn't have the slightest idea how to act professionally in these environments. So I took it very seriously not to bother Mr. Dylan. They said, “If he needs something from you, he'll tell you.” And there were times when he did, but it was always cryptic.

Like what?

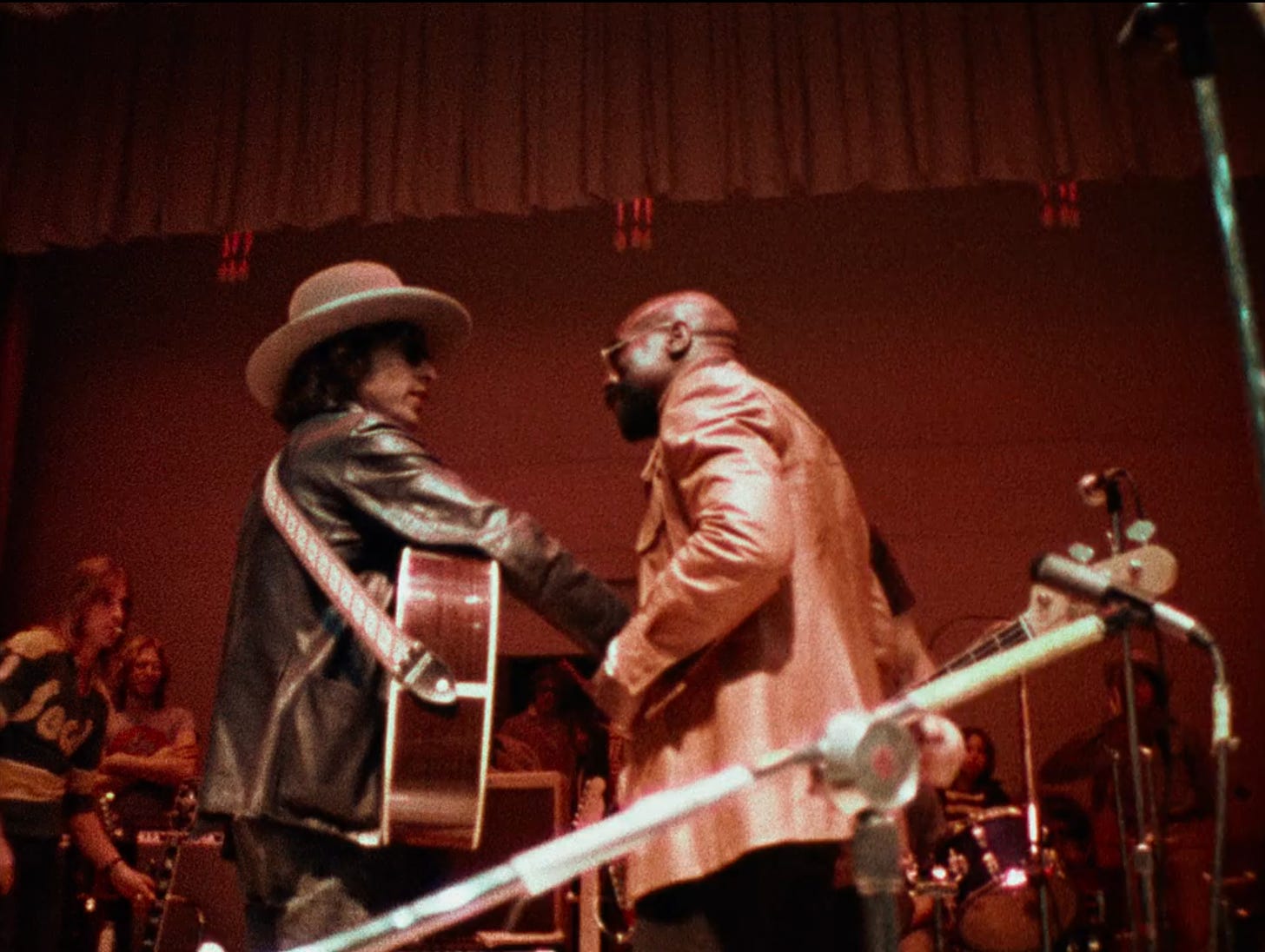

Well, the best story I can tell of him reaching out to me personally, we had done a show in Rochester, New York. This was around when, in the Scorsese film, they visited the tribe [at Tuscarora Indian Reservation]. There was a chief named Rolling Thunder, and they brought him to the show.

My position on the stage every night was stage left. I would sit right behind David Mansfield's position, just behind the PA line. Usually Ronee Blakley would be sitting next to me, or sometimes on my lap. She was very sweet.

I’m watching the stage like a hawk. That's my job. If they need something, I got to be ready to go. I'm new at all this, so it's both exciting and nerve-wracking, because I honestly don't know how to read rock and roll communication at that point in my career.

So I'm waiting for that moment when he's going to want something from me. Sure enough, in the middle of that show, he turns and he looks right at me. I go, “Okay, you got my attention.” I'm watching. Then he gets back to singing what he's singing.

He looks at me again. I'm like, “What does he need?” I'm looking around. What can I possibly be missing that he wants?

Then he turns around to me and very quickly sticks two fingers up behind his head. I figured that out with Ronee’s help. It represented Indian headdress feathers. That was the sign for, “Get the Indian.” So I went down off the stage and got him to bring him up.

That was the level of communication I had with Bob Dylan on that tour. As the years would go on, we'd have more conversations, but, I mean, we've never sat down and hung out.

Going back to Rolling Thunder rehearsals, what else do you remember about them?

There was so much music going on, and so much camaraderie and humor. I remember Roger McGuinn walking in one day with a briefcase that turned out to be the earliest version of a cellular telephone. He was into toys and technology.

There was that another incident at rehearsal that I've never seen anybody talk about. Arlene Smith, the lead vocalist of The Chantels, came into rehearsal late one afternoon. At the end of the night, Bob and Rob, I think McGuinn too, sat on the stage and sang "Maybe" with Arlene Smith.

Arlene Smith was just there to hang out?

I guess. I know nothing of any of the backstory of how she came to be in that room at that time. But I got introduced to her. With an older brother and listening to the radio in the 50s, I knew immediately who the Chantels were. To hear her and Bob dueting on "Maybe" was just mind-blowing.

When the rehearsals were over, we moved on up to the Seacrest Motel in Cape Cod. My partner in crime was really a guy named Kevin Crossley, who passed away about a year or so ago. Kevin was a keyboard guy who was brought on to take care of the piano; he ended up being the piano player in Joan Baez's band. The two of us had to drive the truck with all the equipment up to the Seacrest. In novice fashion, I took a very leisurely drive up the coast, not thinking there was any time I needed to be there. And of course, I was wrong. But we hurried up and got all the stuff up. We set up all the gear and all the towers in which the lights hung, and the roll drop that had the Rolling Thunder logo on it. We set all of that up on the indoor tennis court at the Seacrest. We started doing full show rehearsals down there.

There's that great scene in the Scorsese movie where they’re at the hotel playing for the mahjong ladies.

I knew about the mahjong ladies and all of that, I kind of remember seeing it, but I had very little to do with any of that part of it. I was really learning my craft and doing my job, which was to never leave the stage area except to go eat.

So were you also setting up and breaking down all the equipment every night when you're on the road?

Yeah, at least the equipment that was under my purview, which was the pedal steel, all the amps, Luther's drums, Howie's drums, depending on who was playing. Kevin would look after the piano. Bob had a gentleman named Arthur Rosato; he was Bob's personal guitar tech. I was stage left. Arthur was stage right. Kevin was either side.

I learned rock and roll roadie lesson number one up there at the Seacrest, which is: Never run across the stage.

Everybody else had taken a break and gone to dinner. There was something going on on stage right. I needed to get over there and get something. So I ran over. In the process of running across that stage, I got my foot tangled in the cable that was attached to Bob Dylan's new Telecaster, the brown one that's in the movie a bunch of times. I turned just in time to watch it come right off of the guitar stand and do a face-first header onto the concrete. It crushed a toggle switch and did some other minor damage.

I was obviously well panicked at that point. Arthur came to my rescue. I found him at dinner, got him back there. He fixed it long before they ever came back. Other than me telling this story, I don't think anyone other than Arthur and I ever knew about that happening.

Any other memorable interactions with Dylan in this Rolling Thunder era?

At the end of the tour, after Madison Square Garden, they threw a party for everybody, band and crew. There were two parties actually. There was the end of tour party in the Garden, which took place in the Felt Forum where they had hot dog vendors and New York City street food. All the people who guested on that show were there. Then there was a more private one for the band and the crew at a restaurant bar on 69th and Madison called the Right Bank. It was about a half a block from the Westbury Hotel, which is where most of the band and crew were staying. At that party, Bob had himself gone out and bought Christmas gifts for members of the band. Trinkets and toys.

I was sitting with a couple of friends in a booth. I can't help but keep watching Bob. He was really nervous. They had a little Christmas tree and he's pacing back and forth around this tree. Sara's trying to get him to relax and calm down. I think that was probably more to do with the different women who populated his life being at this party, including Sara, Joan Baez and several other women whose names have escaped me, but have come to light over the years as paramours or what have you.

I can't help but keep watching him from this booth in the corner. He turns to Sara and spits out, “I feel like hitting somebody just for looking at me the wrong way.” And I kind of sank into that booth. How invisible could I make myself at that moment?

Was he referring to you?

I don't think I had anything to do with me, but I was within earshot and I was actually looking at him. Maybe it was the wrong way!

I mean, I’m 24 years old, and this is the most fascinating man I've ever seen in my life. I've been up close and personal with him for six or seven weeks now, but I was genuinely too afraid to go out of my way to talk to him.

Were you involved with any of the filming, the extracurricular Renaldo and Clara stuff?

Only once. We played a show at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, and then went on to Montreal to play The Forum. The night before the show, I got a call in my room. They needed some equipment in the ballroom; could I come down there? They were filming a scene in which Bob Dylan was going to play Robert Zimmerman, and Joan Baez was dressed up as Bob playing Bob Dylan. They were going to film Robert Zimmerman auditioning for a part in Bob Dylan's band. That was how the scene was described to me. They filmed through the night. I was the band's roadie.

Any other Rolling Thunder memories?

I did leave the tour for a few days, because I was a novice and I wasn't that good at my job. They replaced me with someone who wasn't able to go into Canada.

Does replaced mean you were fired?

Yeah, I got canned. I was not at the shows at the Cambridge Theater in Harvard Square. I rejoined the tour when they went up into New Hampshire and Maine, because it was going on into Canada and the guy who'd gone out said he wasn't eligible to go into Canada. He had an arrest record or something like that. So they brought me back two or three days later.

Was there a precipitating incident that led to your dismissal?

No. I was brand new at all of this, and, even though it was the wild west of touring, the other guys on this tour had all more experience. All of those guys were the heavyweights of their time, and I was this new kid. I was acutely aware of how little I knew and was in way over my head.

The other funny thing about it all the way we traveled. I'm sure you've heard the stories of the buses, Phydeaux and Ghetteaux, and the mobile home. As a crew, we had a bus that had seats, like your regular Greyhound bus. They built these plywood bunks over the seats. The very beginnings of what we now call a tour bus. That's how we slept. Nothing the luxuries that people associate with rock and roll tour buses nowadays.

Did you go to the gig at Hurricane’s jail?

Yeah, I'm in the movie in that in those scenes, near Mick Ronson.

I remember us going down there early in the morning and setting it all up. It was like a cross between a public school cafeteria and an auditorium. What I remember most about that was the difference in energies between Joni Mitchell and Joan Baez.

How do you mean?

Well, Joni seemed really timid and taken aback by where she was. Very shy about the whole experience. Joan just dove right in. I mean, her husband had been incarcerated, so she was familiar enough with prison life. She just embraced the opportunity to be a part of their world for a couple of hours. She got down dancing with the guys, doing the boogaloo and the whole bit. Joni was almost scared, in my memory. There was no reaction to what Joni Mitchell was doing from the audience, but the prisoners were totally down with what Joan was doing.

I do want to say one thing about the Scorsese film because I think my perspective on it is a little different. I know it's different from Rob [Stoner]'s. He and I talked about it, and he has a right to be upset with the way he was treated by the filmmakers and by the movie itself. Because he was really a key person to all of that. I mean, calling him the bandleader is almost doing him a disservice, because he was so much more in terms of how that thing came together. That band came together beautifully to support what Bob was doing, and its musicianship was really on display when Joan Baez took the stage, because they sounded like a completely different band. In all the ways that they were raw and ragged with Bob, they were stunning and polished with Joan. I think that kind of gets lost in the soup.

The other thing about the film is that people have assailed it for all of the fictions in it, but I look at it more like a Greek tragedy or comedy. All of those distractions or diversions from the documentary side of things are vehicles to move the story. You have the guy who plays the part of Barry Imhoff, the promoter, and pretty much everything he was saying about the money was actually true. And you have the Sharon Stone character who dropped in and dropped out of the tour, and of course she wasn't a part of it, but there were plenty of other people who did. They were all representative of things that actually happened within that tour.

All of what happened in that Scorsese film was true, in my view. It just didn't happen quite the way they're telling the story, and it didn't happen with the characters they're using. But it happened. You can bring up any situation that was there and I can assure you that something very close to that happened.

Now, having said all that, there's an absolute enormously valuable documentary that could be and should be produced about that whole tour. I was kind of disappointed when they put out the DVD, that there wasn't more documentary footage in there. Just put it out there. Because they told the story, yes, but they didn't give the proper players the right credit that they deserved, especially Rob Stoner.

Let’s jump ahead a large chunk of your career, to the next time you intersected with Dylan. Was tour managing for Steve Forbert in 1988 the first time you were back in the mix?

Yeah, we did a lot of shows opening for Bob. Steve had just put out the album Streets of This Town, and we were doing some solo dates.

We were in a dressing room in Pittsburgh in the old Civic Arena, just Steve and me, and Bob comes in to start talking to Steve. I’m just sitting there, part of the conversation but not in any way the focus of what was going on. But he said something that stayed with me all these years. He's talking about how he just felt really stagnant, like things just weren't going anywhere for him, and then he said [Dylan voice] “And then I got lucky. I hooked up with Tooommm Petty.”

Now what was his name on the Traveling Wilburys? Wasn't he Lucky Wilbury?

Yep. And “You Got Lucky” is a Tom Petty song too.

That's how he viewed playing with Tom Petty, as a stroke of luck that inspired him to do other things. I obviously can't say it with any authority, but I believe it to be the genesis of his character's name within the Wilburys.

Having tour-managed a few people who toured opening for Dylan, is opening for Dylan a good gig? Is the audience supportive? Is the pay decent?

I couldn't talk to you about the pay; I don't really remember whether Steve got five hundred dollars or five thousand dollars. I don't remember what New Bohemians received when Edie Brickell was opening for Bob in in Europe in ’89. I probably have a suitcase full of contracts that I could go back and look at. But, yeah, audiences were absolutely receptive. It wasn't a metal crowd. The metal crowd doesn't care who the opening act is; they just want to get the next band on.

You're gonna get beer cans thrown at you.

Right. The audiences were great for Edie especially. We went all over Europe, met Ringo Starr, met George Harrison.

How did that happen?

We did a show in the town of Fréjus in France, which is down near Nice, and Ringo came and hung out that whole day. That was great, because Bob wasn't anywhere to be seen. And with the New Bohemians, we'd had to check out of our hotel, so we were there early. All afternoon on a hot summer's day in the south of France hanging out with Ringo Starr.

It was kind of funny because that tour’s where Edie met Paul Simon. Well, she first met Paul Simon when we had done a show at the Bottom Line right after we had done Saturday Night Live in the fall of ’88. Then we're out on tour in the summer of ’89 with Bob, and Paul is on tour in Europe. Bob's chasing after Edie and Paul's chasing after Edie and I'm kind of caught in the middle as her tour manager, trying to help facilitate this, that, and the other little trysts that are going on.

Well, one of them worked out real well. It became a lot more than a tryst. [Brickell and Simon have been married since 1992]

Yeah, I think she chose wisely.

So what do you mean you're facilitating?

Like she flew off to spend a day or two with Paul, and Paul's tour manager and I helped put all that together, so it was done quietly. Just doing what a tour manager would do. Logistics.

Was Bob actually chasing after Edie?

Yeah. There was one night, in Milan maybe, when he had given Edie some some sort of embroidered coat. Maybe like a Radio City Music Hall jacket or something, I forget exactly what it was. The next night he wanted it back.

So he comes down to Edie's dressing room while they're on stage, and he's looking around. He said something to my wife at the time, like, “Uh, it's a really nice day out…” and then walks away. Then his wardrobe person came down to our dressing room a few minutes later, got ahold of me, and said, “Do you know where that jacket is that Bob gave Edie?” I pointed to Edie, who was wearing it on stage.

You mean he'd given it to her the night before when they were together?

Yeah. It was a loan, and she thought it was a gift.

So your interpretation of that first interaction was he was trying to play it cool, not make it obvious what had happened?

Yeah. He was just trying to see if it was there or whatever. Far be it from me to have any idea what went through his head.

Since we've talked about two of the three opening acts you tour-managed already, how about the third, Dave Alvin in ’98. What do you remember about that one?

I moved out to Los Angeles in 1990 and by late ’91 I was working for his then-manager Shelley Heber. Dave was putting together his first solo album Blue Boulevard. I helped out with all of that and helped get him on the road. I was managing two other bands at the time myself, a guy who'd been in The Dictators, Scott Kempner, and a band out of Missouri called The Skeletons, who were kind of an early Americana rock band. Dave couldn't really tour—there was no money in it for him—so I put together a European tour with The Skeletons backing up both Dave and Scott. That became a bit of an American tour that actually launched Dave's touring career. This is before the Dylan thing, but that's how we became friends.

As years would go on, I helped out every time I could. He called me up one day and said, “Joni Mitchell is opening for Bob, they want to throw somebody to the lions, and I need somebody out here who can help look after me. Would you do it?” Of course I did.

That was, again, just great. I got to see Joni a lot live. She was really very sweet. She actually remembered me from the Rolling Thunder stuff, or said she did.

The biggest story I could tell has nothing to do with Bob. We played again in Toronto, and the next show was Madison Square Garden. I needed to get back to the city for something the next morning, and Dave wasn't going to drive a van all night to get back. Joni said. “I’m flying. Take my bus.” So I got back to New York as the sole passenger on Joni Mitchell's bus

Did you witness any Bob and Dave interactions like you had with the other two?

No, no. Those were the days when I learned the meaning of the hood. Jeff Kramer, who’s been part of Bob's thing for a long time, and I were friends from his days as an agent back in in the early ’80. That's what Jeff explained that to me: If the hood is up, just leave him be.

And was the hood up a lot?

Yes. Most of the time. [laughs]

The famous hood. Everyone keeps telling me about the hood-code.

I was teasing my my wife last night. I was production manager at a venue upstate in Canandaigua New York called C-Mack for a long time. We did a lot of shows with him there.

We were all staying at the same hotel. My wife had dropped me off at work and was on her way back to to the hotel. Driving into the parking lot, there's some guy on a bicycle, very wobbly, with a hood on. He almost runs into the car, and he stops and he looks at her. And it’s Bob. She sort of smiles at him, and he just rode on. Then she came to me and goes, “I almost hit Bob Dylan with our car.”

I just asked, “Was it intentional?”

You mentioned these sort of miscellaneous other gigs you worked on. Lewiston, Maine [in 2008] was one I was at.

These were all part of the same the same era when I was working as a promoter rep and production manager. The Lewiston gig stands out also because of its history of boxing and Bob being such a boxing fan. I remember giving Tony Garnier some articles about the boxing stuff that had taken place in Lewiston that he brought to Bob. He then came back and said, “Bob says thank you.”

Through all of those years, from 1975 through really 2011 or ’12, I’ve always felt completely anonymous. I mean, I just I do my job. He's a busy man, a lot of people want his time and his attention, and I had no illusions. Like Barry said, he was never going to be my friend.

One day, in either 2009 or maybe 2011, it was at Canandaigua. My son had been fooling around with George Receli’s drums. I knew all the guys, so I asked, they said it’s fine. My son had been taking music lessons. George came in and heard this kid. He shows my son a couple of things on the kit. It was lovely.

Anyway, they're doing soundcheck and I was standing talking to the monitor engineer Jules, who's also since gone now. Jules and I were talking, and Bob walks over. I take a step back so I'm not in their conversation. Bob was asking Jules to pull up a recording of something they had done at a soundcheck a few days earlier. Apparently Jules recorded all the soundchecks that they did. So he goes fishing for that tape, hands him the tape, and Bob turns to walk away. He then turns back, takes his harmonica off his rack, hands it to me, and goes, “That's for your kid.”

So Bob had seen or heard about your kid running around playing drums?

Yeah, but more than that, it meant he actually knew who I was. Everybody's always told me that he was extremely observant, that he knew a lot more going on than we think. I still actually have the harmonica on my shelf. My son said, “It'll mean more to you, dad.”

I've been party to lots of great stories about him that that I wasn't a witness to. A long time ago, they were playing in Santa Barbara, and at the end of the set, Bob comes off. They have a little pipe and drape area that's called the “quick change room” where Bob can have something to drink, change his jacket if he wants to, whatever he needs to do while the audience is cheering before he goes back on stage. The only ones ever in that room usually are his wardrobe person, [stage manager] Red, and sometimes Jeff Kramer. That's where he'll sign an autograph or two. At least in those days, he would sign two things every night.

Anyway, they’re in Santa Barbara and Ringo Starr walks into the quick change room. They exchange some small talk, then Ringo said, “I’ve got to get out of here. You got this show to do.” Bob just turns to Red and said, “Who let Ringo in the quick change room?”

Like it’s someone’s fault for letting Ringo walk into the quick change room! Who's gonna stop Ringo Starr from going anywhere?

I did get his autograph on the Dave Alvin tour. I had an album flat, just the cover, of the Royal Albert Hall concert. Bootleg Series Volume 4. I had a brand new Sharpie, and I asked Jeff if if he would have Bob sign it for me. He said, “Absolutely.” I gave him the Sharpie that night, and he takes it into the quick change room. He comes back and says, “Well, he would only sign two, and I had to get these two done.” Okay, fine, we'll do it tomorrow night.

I didn't get my Sharpie back, and he kept the flat. He got it signed the next day with a crappy Sharpie. He had to do it twice. It’s the most blurry, faint autograph one could ever have, but I watched him sign it so I know it's him.

You were in the quick change room?

I was outside the quick change room, but they were getting ready to come back out so the curtain was slightly open. I was only out there waiting to get my autograph back. It hangs on my office wall now.

Thanks Rich for taking the time to talk! To hear about other parts of his career (including some great Jim Carroll stories), listen to his appearance on Roadie Free Radio.

Another fascinating interview! Ray, your interviews are collectively forming a kind of pointillist perspective of Bob that is different from any of the broad-brush biographies and critical tomes. Thanks for your service!

GREAT interview and post... these first-hand stories and context about the artists and gigs from another time and place are priceless... The observation that Dylan seems to be always acutely aware of the people and small details going on around him (while those around him detailing the story perceive they're not on his radar and invisible) is fascinating... this perhaps has relevance to his work as an artist seeing and articulating bigger, monumental truths from the small details 99% miss... He's just so aware of the world around him, absorbing the constant swirl of events, places, encounters and people.