Richard Alderson on Recording Dylan's Gaslight and 1966 Shows

1962-10-??, The Gaslight Cafe, New York, NY

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Dylan shows of yesteryear. If you found this article online or someone forwarded you the email, subscribe here to get a new entry delivered to your inbox every week:

Update June 2023: This interview is included along with 40+ others in my new book ‘Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members.’ Buy it in hardcover, paperback, or ebook here!

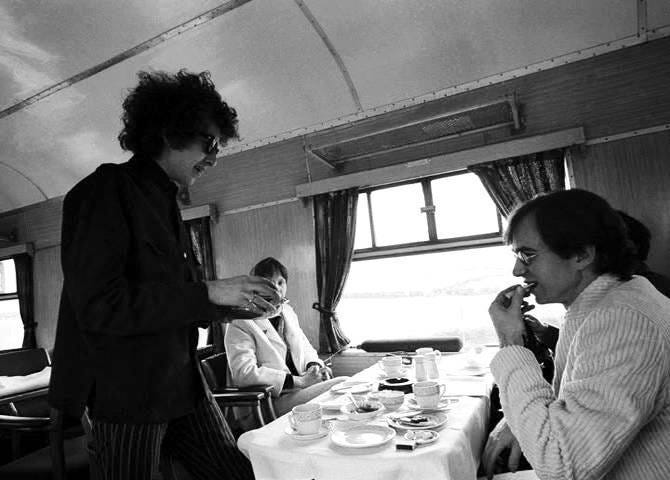

“Most people identify me with Dylan,” Richard Alderson says, despite his work with Dylan only being a blip in a long career. Two blips, actually: He first recorded the famous Gaslight 1962 show and then toured as Dylan’s sound engineer in 1966. You wouldn’t have heard “Judas!” without Richard’s recordings. Here’s a short documentary about Richard’s work there, released to promote the 1966 box set:

But, when I called him up recently, we focused mostly on that Gaslight recording, known as the Second Gaslight Tape (the first was in ‘61). Though the exact dates are unclear, Alderson says this tape combines two nights in October, after-hours showcases for Dylan to try out some new material. The first night, Alderson says, Dylan performed the traditional folk repertoire he’d been doing around the Village for a year or so. Then on the second, Dylan played early versions of new songs like “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

This recording is the earliest Dylan concert to get an official release; the album Live At The Gaslight 1962 came out in 2005. As Alderson will be quick to tell you, though, that album does not tell the complete story, compiling only ten of the seventeen songs and using bootleg versions rather than his master tapes.

Here’s my conversation with Richard Alderson about the Second Gaslight Tape and much more:

Let's start at the beginning. What was your entry into the Greenwich Village scene in the ‘60s?

I originally got there in 1955, when I was 18. I came to Greenwich Village from Lakewood, Ohio. I had been to Greenwich Village as a tourist with my parents. And I knew that's where I wanted to live. So I came on a Greyhound bus with $75 in cash in a little tiny rucksack with my books and a change of clothes in it.

I thought I knew a lot about classical music, so I went to Sam Goody's, which was his original store before it became a chain. I went there thinking I would get a job as a salesman. And of course, they laughed at me and gave me a job in the mail order department, where my classical knowledge didn't have any application. But I was glad to get a job and I stayed for a couple of years.

Then I went back to Ohio. Because I had worked in Sam Goody's, I got a job at a record store. Hi-fi was always my hobby, and I opened the hi-fi department at the record store in downtown Cleveland.

I had heard when I was in New York about a job that was coming up. Somebody called or wrote me from New York and said the job was available. And so I came [back] with my new wife, who was pregnant at the time with my first son.

What was the job?

It was installing hi-fi equipment for Thalia Hi-Fi Audio, which was originally on West 96th Street and moved to Madison Avenue and 65th Street. I installed hi-fi equipment for all kinds of rich people and well-known musicians.

Right around the corner from the store lived Sherman Fairchild, who was the richest man in America, although I didn't know that. He owned the greater portion of IBM, which was willed him by his father. Sherman was a very odd duck. He was a confirmed bachelor and he was also a hi-fi enthusiast. He had his own audio company, Fairchild Audio, which never made any money. He hired me to be his personal audio assistant. He was impressed with some installations that I did for his millionaire friends. That was the beginning of my professional audio career.

Fairchild gave me a mono recorder, a Kudelski Nagra, to use. Through him, I befriended Bob Fine, who recorded all the early Mercury Living Presence records. He became my mentor and he gave me a bunch of microphones. The first Bob Dylan recording I did was with that Nagara and my microphones. And it was at the Gaslight.

When you showed up at the Gaslight that day, were you involved in the Village scene? Did you know who Bob Dylan was?

Yeah. I lived at 148 Bleecker Street and I became friendly with Edward Herbert Beresford Monck, who was known as Chip Monck. He was a famous character in the Village. He convinced everybody from Harry Belafonte to Nina Simone that I was the greatest recording engineer since Tom Edison. He convinced The Village Gate to put in a sound system of mine.

He knew the new owners of the Gaslight, who were the Hoods, and they had never had a sound system. So I put in a modest two speakers. It was a tiny little room that held 50 people at most. I mean, that room really didn't need any amplification, but the Hoods wanted to attract more people there.

There were so many folk clubs around there at the time. What was the Gaslight's reputation? Was it just one of many?

One of many, but the Hoods were very nice people. They were more idealists than businessmen. Clarence Hood was the father. He came from Northern Florida and had a fair amount of money. I think he was a millionaire. But the room never made much money. There was no admission fee when they opened it. People would perform and they would pass around the basket afterwards. The performers got a percentage of it and the owners of the club got a percentage. So nobody made a lot of money.

Were you recording a lot of different artists in those clubs or was Bob Dylan unusual?

I did some recording at the Village Gate surreptitiously. I recorded Thelonious Monk; it was issued a while back as an LP. And Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane. Those were all recorded surreptitiously with one microphone in the ceiling, so they weren't great sound.

Did you put the microphone in the ceiling when you created the sound system?

I just kind of snuck in and put the microphone in the ceiling. It was only there for about a month. I took it down because I wasn't interested in being a bootlegger or recording things surreptitiously. I wanted to stop it before somebody noticed.

So what was the story behind you recording Dylan at the Gaslight?

Chip came to me and said that Dylan had some new songs and was going to perform them. Dylan hung out at Chip's place. He had a room at the Village Gate. Dylan would come in and type away and drink red wine and opine on various subjects. He was a charming young kid who had some talent, but nobody expected him to write the great songs that he was going to write.

It was two nights in a row and I think they were one night after the other, but I can't be sure. The first concert was the old Bob Dylan and the second concert was more or less the new one. It was obvious from the second night on that Dylan was headed for fame.

What was he like as a performer? He had started writing great songs by that time, but did he have stage presence, or was he awkward?

Kind of combination of all of them. As he wrote great songs, he grew into his personality. I would rate him originally as kind of mediocre. When he started to write songs, he was the top of the heap. He went from one thing to the other.

I went there and I recorded it and I played it back for Dylan at my studio in Carnegie Hall. I gave copies to his manager, from which the bootlegs must have originated because I don't remember ever giving them to anyone else.

Do you remember Dylan's reaction?

We smoked a joint and Bob was very happy with the sound, but I felt that he was more focused on his studio recordings for Columbia. Many of the songs are better than they were [on the records]. Certainly "Hard Rain's Gonna Fall" is better on the Gaslight tapes than anywhere else.

Was there talk of releasing them as a live album then?

No. I think that Columbia didn't know much about live recording. And he hadn't voiced his originality in public. These concerts at the Gaslight in '62 were after hours, and they were more testing material than anything else.

[When Columbia eventually released Live At The Gaslight 1962 43 years later], they said they searched everywhere for the best possible recordings, but they never came to me. I had the originals all along. They just downloaded a bunch of stuff. It sounds pretty good, but my copies were one-offs directly from the master tapes.

Bob Dylan's office [subsequently] bought the original Gaslight tapes from me. They own them, but because they released them once with false album notes and claimed a lot of bullshit, unintentionally, about the recordings, they don't want to issue them again.

Wait, so the official album was your recording, just several generations later, or a totally different recording?

They were my recordings but they were mishandled. I gave the recordings to Dylan's manager, Albert Grossman at the time. I suppose that the copies that were on the internet were copies of copies. But they were really bad versions. Not at all like my tapes.

Did you have any interaction with Dylan or Grossman between the Gaslight era and the '66 tour?

No. When it came time to do the '66 tour, Bob had already gone electric and was looking for somebody that knew amplification. I was one of the few who did. Harry Belafonte was the first person to use his own sound equipment and have it written into his contract that his sound engineer had to do all the concerts. So I got indoctrinated with Belafonte and I kind of spread it around. I did a bunch of other concerts for Grossman like Peter, Paul and Mary, but I wasn't really interested in doing live sound. I was interested in having a recording studio and being a recording engineer. The live sound was a way to make money. It was a paycheck.

I knew about the Hawks. And I liked his newer songs, certainly. I've remained a fan all along, although I've never seen Dylan's set [since].

What is it like trying to amplify a rock band in those rooms?

None of these places were designed for music, and it wasn't really loud enough for the electric band. The acoustic set was fine. Dylan and his guitar were very well amplified, but the band - the drums were loud and the guitars were loud and sometimes the organ. It was difficult to make a good balance because this stage balance wasn't good. People would play loud.

Do the recording of those shows sound better than it did to the audience at the time?

It's the very same audio. Some of them were good; some weren't. The acoustics of the room had more influence than any of the equipment, because the equipment was always the same. Some concerts were very successful. And some concerts were underamplified and, some concerts, the balance was all wrong.

Do you remember any particular rooms that were challenging?

Royal Albert Hall was a big problem, because it seated about five or six thousand people, and the average place that we performed in was just a couple of thousand at most. We would typically use some speakers that were in the hall, but Royal Albert Hall was designed for acoustic music. It wasn't designed for amplified music.

Dylan had a very good idea what he wanted, but it wasn't available at the time. There was nobody doing amplified sound for rock concerts, period, until a year later. It was started by The Who.

Did that cause tension between you two, on nights when Dylan wanted a sound that your equipment wasn't up to the task of delivering?

Yeah, yeah. But he knew that my limitations were forced on me by circumstance. He just wanted to have it better. And it wasn't. He never took it out on me.

From your vantage point from the side of the stage at all these shows, was the audience as hostile as its legend?

I would say that sometimes it was more hostile than others. Never any more than 20% of the people were hostile. Vocally hostile - maybe the others were quiet and hostile. There were very few concerts where I felt that it was all negative. There were those who thought that Dylan should stay acoustic and stay with the folk music team. They were very vocal. And they were encouraged by the press.

Do you remember if you heard the famous “Judas” yell in the moment?

No, I didn't. I didn't pay any attention to it. It all flowed together and I didn't notice it particularly.

It's interesting that capturing that moment on recording has made that specific show so legendary even compared to the others.

I always felt that Dylan was a rock and roll artist. I never felt that he was a folk artist. Most of that is my particular prejudice. But he became a folk artist because that was the only way that he could express himself. Nobody wrote serious rock and roll songs until Dylan did.

1962-10-??, The Gaslight Cafe, New York, NY

Thanks to Richard Alderson for taking the time to talk! He says he’s halfway through writing his memoir, Open the Door Richard, which he hopes will come out in about a year.

Find the index to all shows covered so far in this newsletter here.

Update June 2023:

Buy my book Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members, containing this interview and dozens more, here!

Wow. Some fascinating stuff. As you get older you appreciate great sound engineers more and more. Great connection there with Fairchild, famous in certain quarters for many things, including

Fairchild SemiConductors. Anything I can read on Richard Alderson, from his ESP days,

through Dylan and then onwards is interesting. Akin to Dylan's producer in the early days Tom

Wilson. I hope he writes a book someday.

Mostly accurate except for the misspelling of Chip’s last name-it was Monck. The rest of the errors are mine..