Pianist Alan Pasqua Talks "Murder Most Foul," Dylan's Nobel Lecture, and the 1978 Tour

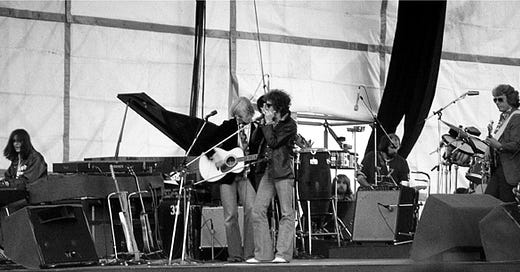

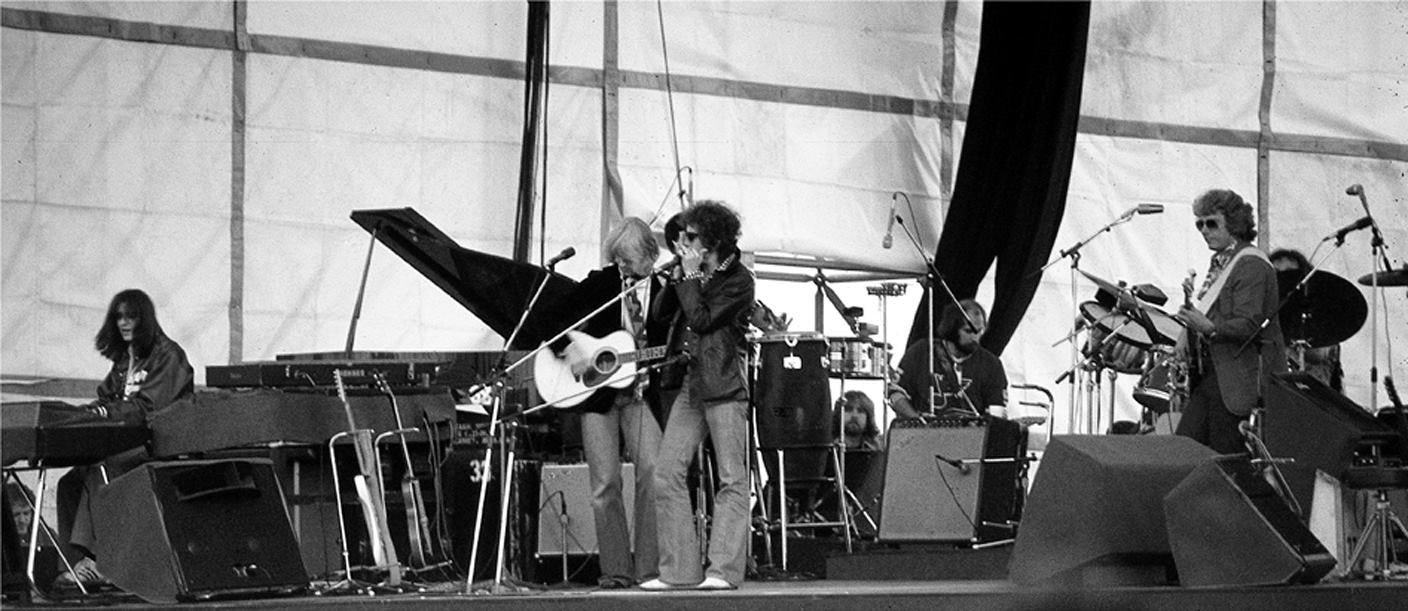

1978-03-27, Entertainment Center, Perth, Australia

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan shows of yesteryear. Free subscribers get one or two posts a month, paid subscribers get several times that (and can even assign me a show to tackle). If you found this article online or someone forwarded you the email, subscribe here:

Update June 2023: This interview is included along with 40+ others in my new book ‘Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members.’ Buy it in hardcover, paperback, or ebook here!

Alan Pasqua has one of the more unusual histories with Dylan of any of his many backing musicians. In 1978, he played 115 concerts with Dylan, Bob’s longest tour to date. When the tour finally ended, they went their separate ways.

Pasqua didn’t hear from Dylan again for 39 years.

Then, in 2017, he gets asked to record a piece of piano music for Bob. For what purpose? They won’t tell him. So he records something, sends it off, and soon after finds himself a new character in the Nobel Prize drama, as Bob recites his long-awaited acceptance speech over Alan’s recording.

Soon after, Pasqua’s actually in the studio with Bob – for the first time in 40 years – to record a gender-swapped cover of “She’s Funny That Way.” Then last year, just before lockdown, they collaborate again on “Murder Most Foul,” which was unveiled to the world exactly one year ago today.

So though I primarily called Alan to talk about that long tour in ’78 – represented today by the March 27 show in Perth, Australia – we ended up going through his entire history with Bob, from 1978 through the 2020 “Murder Most Foul” session.

I've read short versions of how you got involved in the '78 tour, but I wonder if you wouldn't mind telling me the longer version. I gather you were with Eddie Money at the time?

Yes. My first gig after college was with Tony Williams and The New Tony Williams Lifetime. When that band dissolved, I moved to Los Angeles. The guy that produced the New Tony Williams Lifetime records, his name was Bruce Botnick. When I got to LA, he was the only guy I knew, and I called him. A couple of weeks later, he called and said, "I've got this new artist I’ve been assigned to produce. His name is Eddie Money. We need a piano player to play on his record. Do you want to come over and meet him?"

I had come from a jazz background, but I had played rock as a kid, so it wasn't something that was foreign to me. I walk in and Eddie says, "Hey, Al, I don't want to hear any jazz shit from you!" [laughs] Then he sat down at the piano and played me what were going to be his two first big hits, “Baby Hold On” and “Two Tickets to Paradise.”

We went out on the road. I think we were in New York doing a rehearsal. We were on a break, and I was standing in the hall, and there's this other guy in the hall. We just kind of struck up a conversation. I forget what band he was there working with, but he said he was going to be playing with Dylan. His name was Rob Stoner. He says, "I'm going to be in LA down the road if you want to exchange numbers, I'll give you a call when I'm in town."

I did this three-month tour with Eddie that ended right before Christmas. I get home and I'm just kind of sitting on the couch, decompressing, and the phone rings. It's Rob. I was living close to Santa Monica, near the Marina, and he said, "Man, I'm in Santa Monica at Bob's rehearsal studio, and I'm putting a band together, auditioning people for next year for a tour. I'd love to get you in on it."

I was so burnt out from the last trip with Eddie. I said to him, "Man, I just got home and I think I'm going to take a break." He said, "Okay, well, good talking to you.” I hung up the phone.

Five minutes later, I just thought to myself, "Oh my God, what did I just do?" I called him right back. I said, "Hey, man, I'm feeling a whole lot better! I'd love to come down and hang out." I went about a mile away from where I was living, down to Bob's rehearsal place. It's a big room with tape recorders, nothing super fancy, just stuff to record music on. Rob was the only one in there.

We just started playing some blues and shuffles. He thought he heard something that might be a good fit. He recorded all this stuff, and he put together a tape of me and presented it to Bob. A little bit of time goes by and Rob calls me and he goes, "Let's do it again." I go back down, we do it again.

After that, I got a call saying, "Hey, we're putting a band together, do you want to come down and play?" The very first day there were at least, I'm not exaggerating, two or three drummers, three keyboard players. David Mansfield was there, Steven Soles, Billy Cross was there, probably another guitar player, Rob of course, Steve Douglas, I think Bobbye Hall was there or came shortly thereafter. Bob showed up and we just started jamming. We weren't really playing any specific songs. Then we were excused.

A couple of days later, it's like, "Hey, we're going to do it again.” That time there were two keyboard players and two drummers. They started narrowing down the field.

This went on for maybe a week or two. I didn't think I necessarily would get the gig, but the longer I was there, the more I was really into playing with Bob and this band of great musicians. I walked in one day and I was the only keyboard player there. Nobody said to me, "Congratulations, you've got the gig." With that world, you've got the gig for that day. Depending on how things go, maybe you'll have the gig tomorrow.

The band solidified and we got it down to me, Ian Wallace on drums, Rob on bass, Billy Cross, Soles, Mansfield, Steve Douglas, Bobbye Hall on percussion, they brought in three background singers, and then we started working on tunes.

I remember there was one day where it was not a good day at all and all of us were dismissed. Then the next day, we all got a call and all of us were brought back in.

So you were fired for 24 hours?

Yes, we were fired for a day. At least I was.

Bob was a really great, great bandleader. I was lucky to play with Tony Williams early on in my life. He learned from Miles Davis. Miles never told him what to play, but by how Miles played, he showed Tony what he needed to do. I found Bob to be quite a bit similar to Miles.

I never wore my jazz hat in that band, but I let a little bit of that influence leak in, ever so slightly, where I thought it was okay. I didn't know at that time that Bob was a jazz fan or even listened.

Were you a big Dylan fan at the time? If he called out something that wasn't a Greatest Hit during rehearsals, were you likely to know the song?

I was flying blind! He asked me one day if I knew “Positively 4th Street.” I freaked, because I didn't know it. I just looked at him and said, “No, man, but I'll learn.” He just looked at me and started laughing. He turned to one of the other guys and said, "He said he'll learn it!” I thought, "I'm gone, I'm fired, that's it." [laughs]

Maybe he appreciated my honesty or my naiveté or whatever it was. I just tried to be myself and enjoy the ride for however long it lasted. It's been interesting that he and I have intersected throughout the years. It's always been a joy for me.

I want to get to those other intersections later, but sticking with that ’78 tour, what do you remember about the first shows? They made the live album so early on, the earliest shows in Japan became most famous.

It was something that I'd never experienced. That was his first time in Japan, if I'm not mistaken. It was like the Queen. It was like royalty. That's how much he mattered to them, coming over there. It was really incredible.

I've got a crazy ass story. I was playing ping pong before one of the shows with this guy from China who was just insane, a professional ping pong player. He hit a shot and I went for it, and I ran smack into steel pole and put a giant gash in my forehead. The tour manager looked at me and went, "Oh, shit. Wrap it up."

They put me in a turban, like a tourniquet on my head, and pumped me full of Tylenol and said, "Get out there and play." I remember the first bass note, I was like, "Oh my God.” But we played the show, and it was a long show. Then after the show, they took me to some-- I don't know if it was a hospital, I just remember it was completely dark and this doctor showed up. They put me on a table and they had to stitch me up. I remember him standing on this plastic milk crate. I was thinking, "how sanitary…"

What was a typical day like on the road? I’m assuming you're not getting gashed in the head every day.

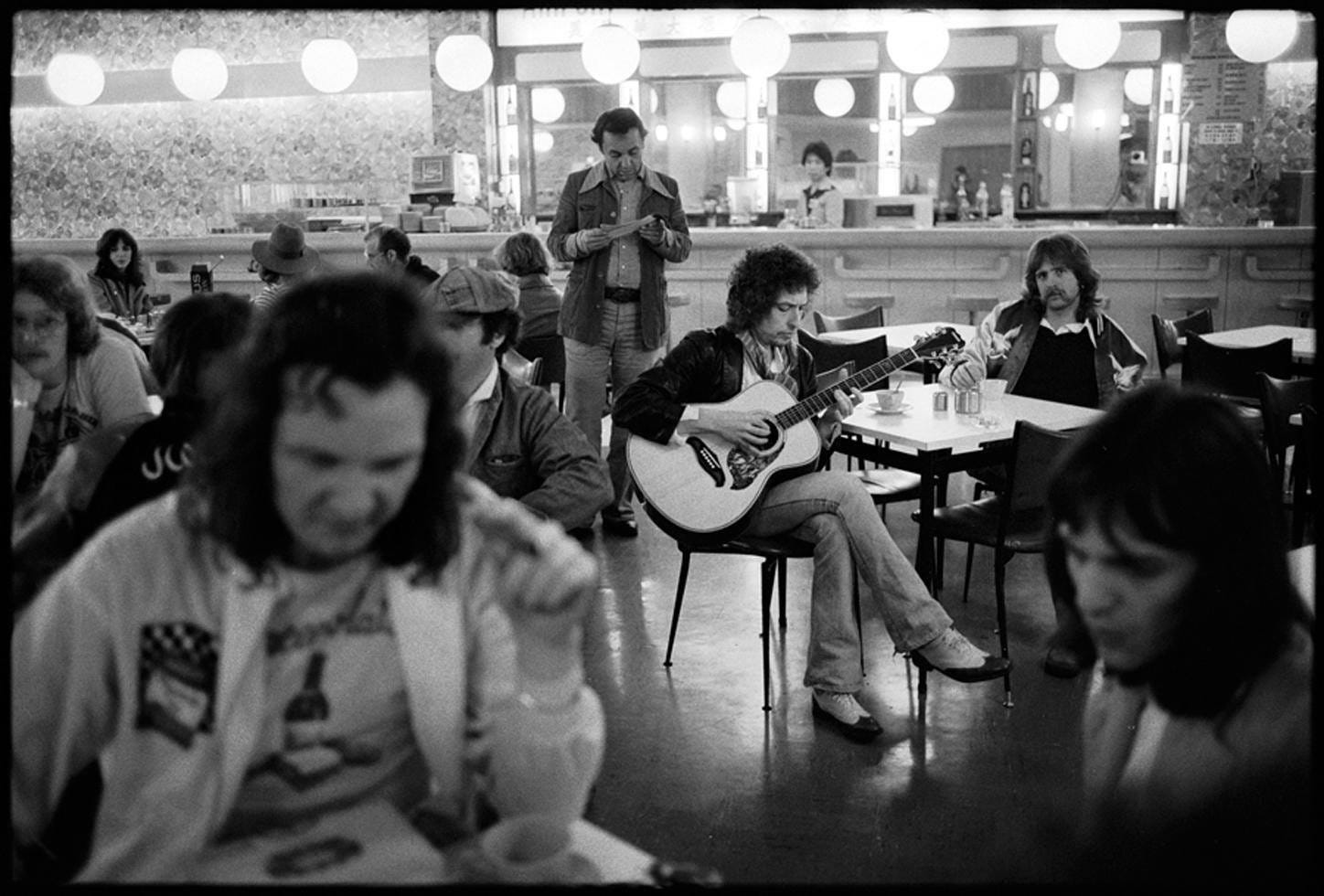

I mean, on any day of my road gigs, there was nothing unusual about it. Soundcheck, maybe rehearsal. I don't think he ever, or very rarely did he call a specific rehearsal to go over things during the day. It was very relaxed. We'd have our lobby call time. They were running a tight ship.

How did you get along with Bob himself, and with the rest of the band?

Look, I've got to be honest, for me to be around somebody like that, I didn't really know how to behave. I mean, I wanted to be his friend and I'm like, "Well, who the hell am I?" The thing that kept us together was that we were all playing music together.

He taught me a lot about how to be a pro. I remember we were in Germany and there were some people in the audience that were planted there, unbeknownst to me. All of a sudden, they started throwing things on the stage. I remember rags soaked in paint were flying by. One of them hit Billy Cross. Bob just stopped, walked off the stage. We followed him. This was not a small gig. It was a big concert, thousands of people.

We're back in our dressing room. We all wore band outfits, and I got back there and I immediately changed into my street clothes. We're sitting there like a half an hour, and all of a sudden, the door opens. Bob comes in. He sees me and he's like, "Where are you going?" I looked at him and I said, "What do you mean, man? I'm just waiting for the bus." He said, "We're not going back to the hotel. I'm waiting for these people to leave. There's 15,000 people out there that came to see us, and there's 20 people in the audience that came to ruin the night. We're going to just wait them out."

I just looked at him like, "Holy shit. Wow." He said, "Get out of those clothes, man. Put on your gear." So I changed back into the stage clothes and boom, we went out and played a two-and-a-half-hour show. I never forgot that. A lot of people would have just said, "Screw this. I'm out of here," and went back to the hotel.

Wait, why were people throwing rags soaked with paint and whatever else?

I don't know. I think it was some political crap going on. [A People magazine concert review from July 1978 mentions “Some leftists, apparently angry at the mellowing of the old polemical minstrel, pelted him with eggs at another gig, in Berlin.” - Ray]

This was Bob's longest tour ever. How did it change over time? Were people getting burnt out by the end?

I can only speak for myself. It never really changed for me. I was a young guy, 26, so I'm seeing the world for the first time. Every day is just like, "Wow, where are we going today? Far out!” It was incredible. I was so grateful to be there.

Every night for that better part of that year, he and I played two duets [“I Want You” and “Girl from the North Country”]. I looked forward to those two duets every night so much because it was a moment just for me to be alone and play with him and get to do a little bit more than I would normally do as a keyboardist in the structure of the band. It was never a burnout thing for me.

I'm mostly focused on live stuff, but given that the Street-Legal sessions were wrapped up in the tour and tour rehearsals, what can you tell me about those sessions?

Oh, boy. It was just a big open room with a linoleum floor. It was not a recording studio by any means. They brought in a mobile truck. We spent a lot of time just trying to get it to sound good.

It didn't take a whole long time to make that record, I remember that. Bob worked on his vocals. We did a number of takes. Don [DeVito, producer] was there, of course, commanding the ship, but it just all went down. The band is new, so we're trying to feel our way in the dark like, "Okay, what do we sound like? Who are we?"

Was that a challenge with such a big band in the studio?

Yes. Ian and myself and Bobbye and Steve Douglas and Billy, we were the new guys. Maybe my life in jazz and playing fusion in college--you have to pick your spot. I listened to earlier records and understood what my role was. It was not about playing wall to wall, necessarily, but making those musical contributions in the space with a band of that size. Everybody had a very specific part to play.

By the time I got to Street-Legal, it was remastered and sounded great, but I know it was criticized at the time for being muddy. Bob had not wanted anyone to wear headphones or anything, so everything leaked into each other. Do you remember that being an issue at the time?

I don't recall that record sounding amazing, and I basically attribute that to the room, not anything else. It's not like you need to be in a chamber with carpet on every surface, but we were in a highly reflective environment with low ceilings. That’s not necessarily the greatest place to record. The good part about that was it was a really big space, so there was air. It just wasn't tall. It wasn't high air, so the sound couldn't go up. It went right or left.

So it's bouncing around and bouncing into your mic, other peoples' mics?

Yes, there was a lot of reflection, and I think people were complaining. I didn't really find it muddy. It sounded more like a live record to me than a studio album, but man, I listen to it now and I think it sounds good.

In terms of the band dynamics you were talking about, did Rob Stoner's departure from the tour early on affect you, since that he had been your entry point into that whole world?

It did. I honestly do not know the details of all of that. [I was] surprised by it and saddened by it, because he was the guy that got me in the door. At that point, I understood what a big machine this was. I knew I was certainly dispensable, so I was like, "Well, this is an amazing gig and an amazing experience, and I want to hang on to it for as long as it will go." I went into a little bit of a self-preservation mode. I wasn’t going to start going, "Hey, man, why did Rob leave? What happened?" because then I probably would have been out the door too!

What happens after the tour ends? Is there talk of continuing?

There was no finality. It wasn't like, "Thank you, guys. It's been a great year. I'm going to move on." It was just like, "We're done with the US. Thanks." There could've been a phone call to come back or there could not have been. Amongst us in the band, we just kept tabs on what was going on, and then we heard that there was a new band.

Now I want to fast-forward, way forward, and ask you about the Nobel lecture recording. I know from some interviews you did at the time that you didn't even know what it was for [as Alan explained to the New York Times, Bob’s team asked him to send them thirty minutes of piano music for an undisclosed project]. As a pianist, how did you come up with something with so little guidance?

They gave me some direction. I prodded because I was like, "What am I doing here?" They used the model of early Steve Allen. Piano musings that are slightly bluesy, but not really. They're not necessarily connected, but they're not terribly random either. That was just enough for me to go on. I said, "I understand. I think I get what you want."

They said they needed a certain number of minutes of music and I say, "Before I give you that, [let me record] three minutes of some stuff and tell me if I'm in the right direction." So I did that, sent it off. I got the call back and they said, "Yeah, that's exactly what we're looking for, so do the rest." I said, "When do you need it by?" They said, "Tomorrow."

What did you think when you heard the end result?

I was honored to be a part of it, and I was also thankful that they were generous in wanting to give me credit for my work.

There was one other thing that I worked on with him [before “Murder Most Foul”], which was that he did that one track on that record, “He’s Funny That Way.” We did that at Capitol. I'm trying to recall if the Nobel thing happened before that. It might have, but I didn't see Bob for the Nobel thing. That was all a phone call, and then I went into my studio with my piano and sent them some music.

I believe the Nobel was probably first. I was just Googling release dates in the background. Nobel in 2017 and then “He’s Funny” came out a year later. I didn’t know you were on that.

Yes. There was a podium where Vince [Mendoza] was conducting the orchestra, and then to the right of Vince was a mic for Bob, and then to the right of Bob was me on the piano.

It was a really interesting day, because I just read the chart that was written for the piano part and I could see that Bob wanted some things differently. I realized at that moment that I was probably the bridge between him and Vince, because I was the only other person in that room that had history with him. I took it upon myself to try and interpret things for Vince that he could relay to the orchestra.

What do you mean “interpret”? If Bob's saying something that is not clear or is not in like musical-notation form for an orchestra?

There might be like a tempo fluctuation, or he might have wanted to put a pause here or something. That stuff might not have been super apparent, but I, having had a year of playing music with him, understood what he was trying to get at. I just took it upon myself to go to Bob and say, "Do you want to do this here? What if we try to do this?" There was a comfort factor. He knew me. He didn't know Vince; he didn't know the orchestra people. I was the bridge, and it worked out really nicely. Really cool song, and it was great to see him. I hadn't seen him for a long time. It was just one day, boom, you're driving home, like, "Wow, that was a great day of music!”

To bring us up to the present, was your next contact the “Murder Most Foul” session?

Yes, yes. Jeff [Rosen, Dylan’s manager] called and said, "What are you doing?" I said, "When?" He goes, "Tonight."

I said, "I kind of have plans, what's going on?" He goes, "Oh, Bob is working and we were thinking maybe of seeing if you had some time." I said, "What other days might be good, Jeff?" and he said, "I don't know. Let me find out and I'll get back to you" and I hung up the phone.

I thought about Rob Stoner's initial call to me about going to the first rehearsal when he was putting the [1978] band together. I said, "Oh, man, if this is going to happen, it's going to happen tonight." I called [Jeff] back and I said, "Look, I'll try and clear a path to make it happen tonight. Give me some details." He told me where it was and all that, so I went to the studio.

Blake Mills was there. Benmont [Tench] was there, who is my hero, one of my all-time favorite musicians and people and the greatest B3 player on the planet. I just think the world of him. We were hanging out, and then Bob came out and it was like, "Hey, man.” A reunion. Then we went into the studio. and they played [us] the song.

When you say they played you the song, what do you mean?

They were playing a demo. I heard it and I just couldn't believe it. In rock music, things usually have a specific beat and pulse. This was free. The time was free. It was elastic. It wasn't specific to a certain time, feel or tempo. It just moved and flowed.

When I was done listening to the track, I turned to Bob and I said, "My god, Bob, this sounds to me like A Love Supreme.” He just stopped and he looked at me. I thought, "Oh, I'm going to get fired" again. [laughs]

Then we went into the studio and two or three hours later, we had just a bunch of different takes and it was like, "Okay, fellas. Thanks. We got it." I left going, "What an amazing night. I hope that what I played makes the record." You never know, you know? I was thrilled to find out that it did.

With the Nobel and that, you're kind of his go-to piano guy for these long epics. One's a song and one's not, but as you say, “Murder Most Foul” is almost as loose as playing piano for a Nobel lecture.

Yes. I don't know if that's true, but if that's my role, I accept it wholeheartedly! Bottom line is I think the world of him and I loved making music with him, and I think that we have some sort of a connection. Musically, spiritually, however it is. Whatever happens in that studio, when people get vulnerable and bear all, it's an amazing experience. It's never work for me. It never, ever, ever feels like work.

I think of him as recording stuff live like you were talking about with Street-Legal, but “Murder Most Foul” is so long. Was that recorded live or were you piecing bits and pieces together?

Live.

All 17 minutes?

Yes.

Wow.

Every take that we did, it was the whole-- Unless there was a stop because I made a mistake or something, then we'd start over. It was all live.

As a piano accompanist for this long thing with so many words, how do you keep your part interesting? How do you keep yourself engaged for such a long track?

In our jazz world, we just lost a dear soul, Chick Corea. I was reading some of his advice that he had typed out for somebody, and one of the things that he said was, "Play so that others sound good as well." It's such a beautiful sentiment. Take your ego out of the picture and be there for the song, and be as selfless as you can, and listen and react to what you hear. By reacting, it doesn't mean you have to play anything. It might mean you play nothing, and then you come in with something.

That's the only way it's ever worked for me. In my teaching of other musicians, I really stress, don't listen to yourself. Don't worry about the notes that you're playing. It's okay to hear what you sound like, but in the context of the song and in the context of the band that's there. You need to be able to not play, as well as play, because that's what creates the magic.

In a recent interview, Fiona Apple said she also played piano on that track. I gather she wasn't at your session, but when you are listening to it, can you pick out who is doing what, knowing what you played?

Yes, I can. Benmont's on the left, Alan's on the right, Fiona's in the middle. It's like the early days of stereo. It's a really cool collaboration. She sounded beautiful too.

Bringing it all full circle, in your recent sessions with him, is there any acknowledgment of your history in 1978? Are you talking about it at all?

No, we don't. Perhaps if we were to hang out or go back on the road, that stuff would come up, but no. I keep things pretty much in the present tense and just let him know how much I appreciate him and how much I love him and how grateful I am.

Thanks to Alan for taking the time to talk! Keep tabs on what he’s up to at https://alanpasqua.com/

1978-03-27, Entertainment Center, Perth, Australia [partial recording]

Update June 2023:

Buy book Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members, containing this interview and dozens more, now!

ICMYI

Freddy or Not [subscribers only]

2004-03-21, Kool Haus, Toronto, ONAfter Prague [subscribers only]

1995-03-14, Stadthalle, Furth, GermanyOne Random Song: "Blowin' in the Wind," Santiago 2008 [subscribers only]

2008-03-11, Arena Santiago, Santiago, ChilePlaying the Electric Violin [free to everyone]

2005-03-07, Paramount Theatre, Seattle, WAThis Date in Dylan: March 3 [subscribers only]

Bob sits with the Grateful Dead and Harry Dean StantonComing up next: A look at Bob’s early-’90s trad. covers, digging deep into the Sinatra years on stage, and an in-depth interview with one of the most beloved band members of the Never Ending Tour.

So great. Loved reading this. I'd love to read an interview with Bobbye Hall about her Dylan days sometime too...

Great interview! I was particularly intrigued by the talk about the 'He's Funny That Way' and 'Murder Most Foul' recording sessions. Can you believe that the latter was recorded live? Too cool.