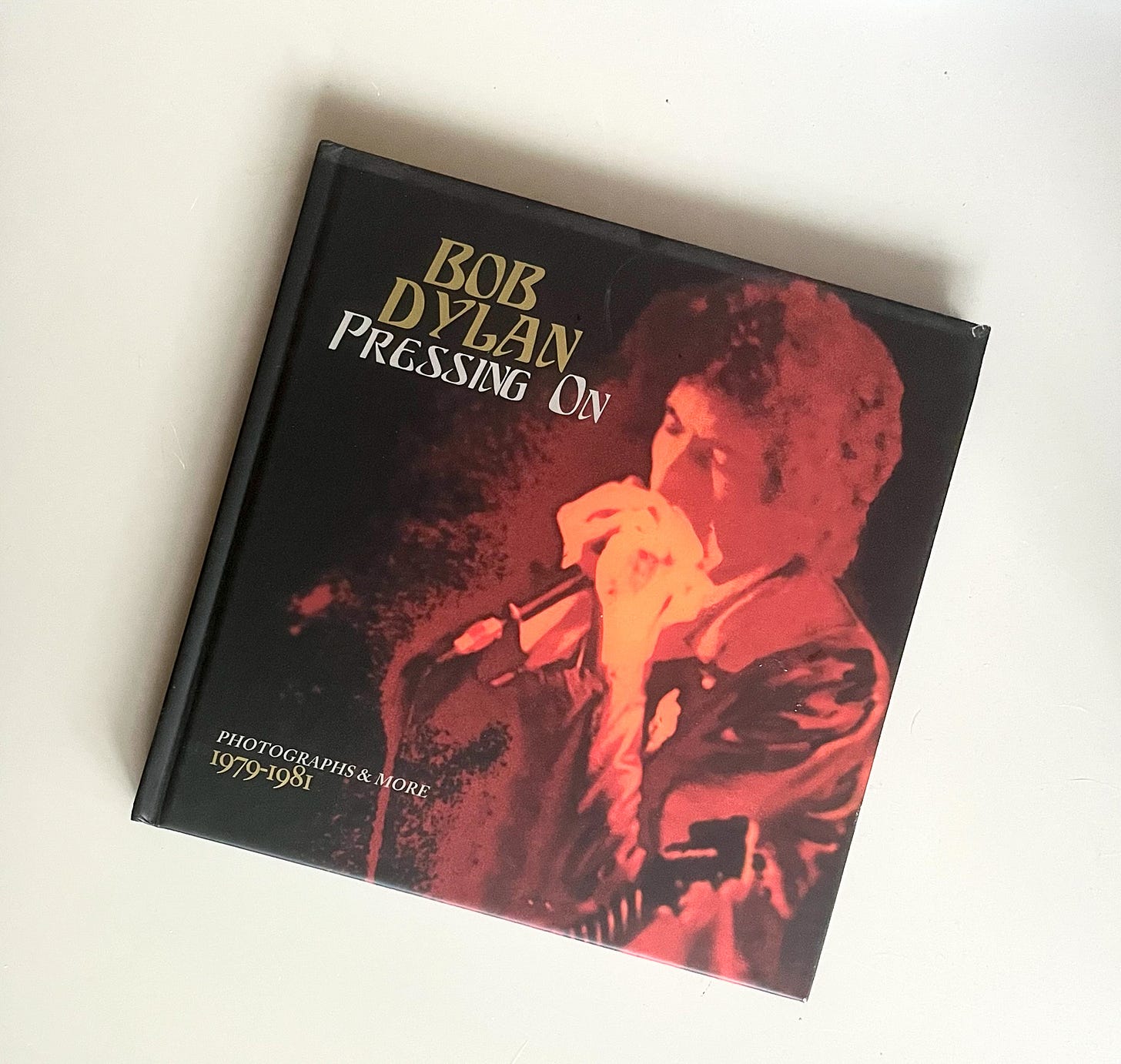

Photographer Paul Till Tells the Story Behind the 'Blood on the Tracks' Cover

Plus a tour through four more decades of Till's live Bob Dylan photos

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

Before we dive in, welcome to everyone who came from the Rolling Stone article! You can read more about the newsletter here and find an index to everything that’s run here. I just started a series on The Earliest Concert Tapes. Half of those—and of all newsletters—only go to paid subscribers, so if you like what you’re getting, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to support the project. (And to everyone’s been here a while and might be saying, “Wait what Rolling Stone article?” you can read it here. Or, if you get stuck muttering small talk at the paywall…here). Okay, onward…

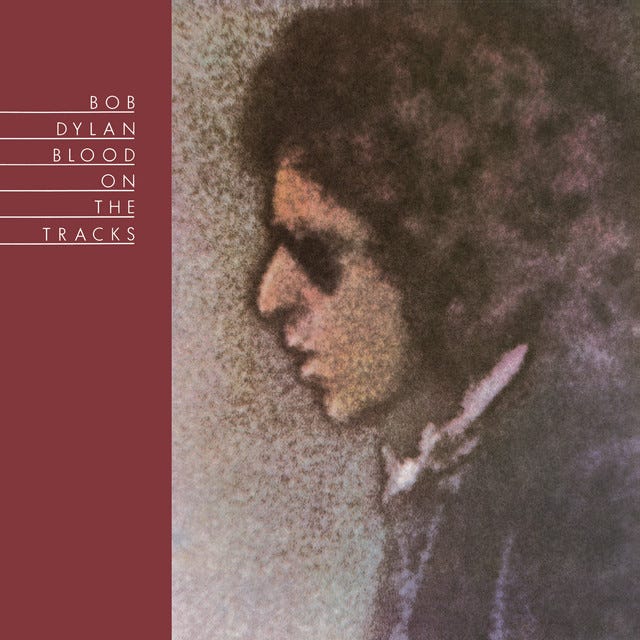

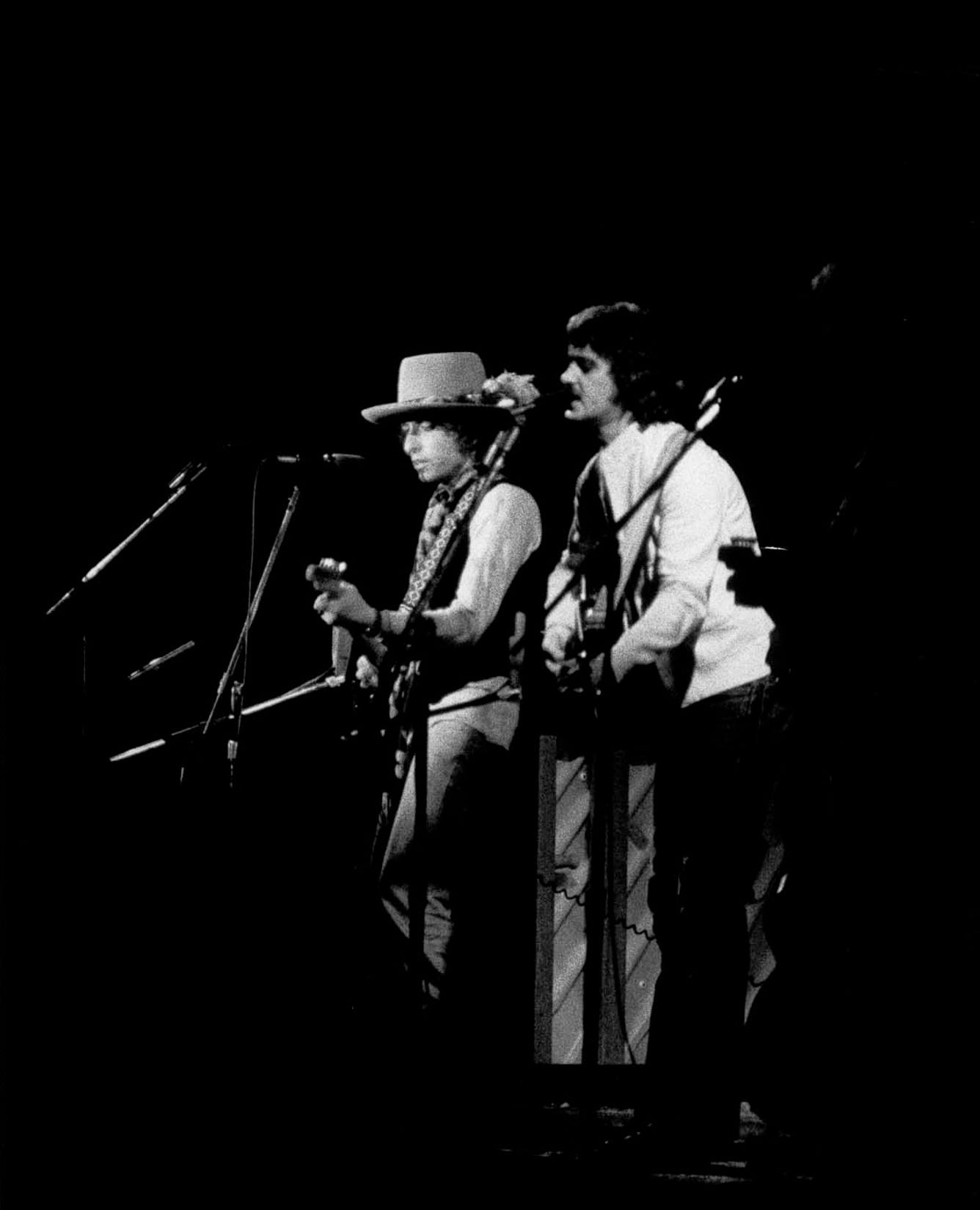

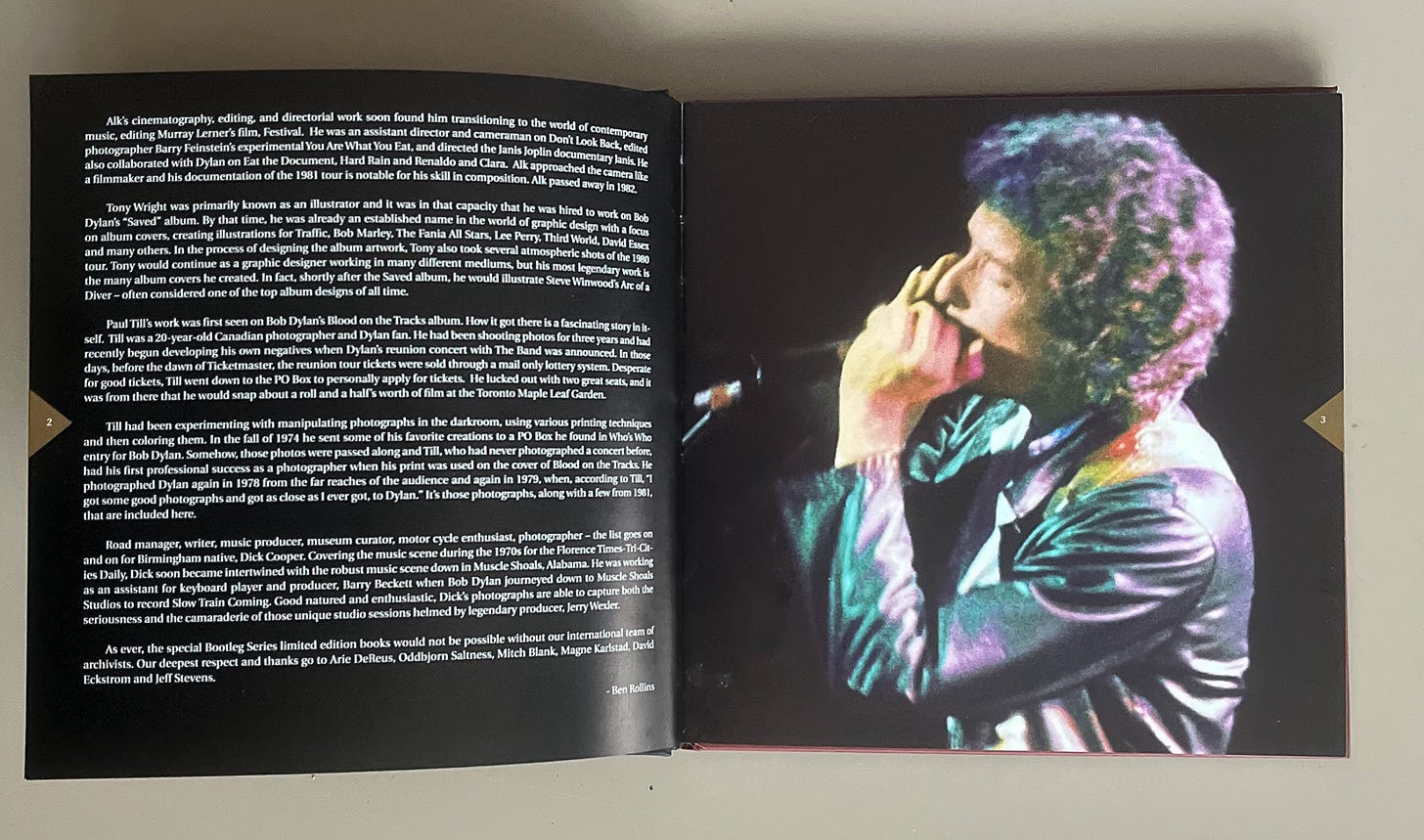

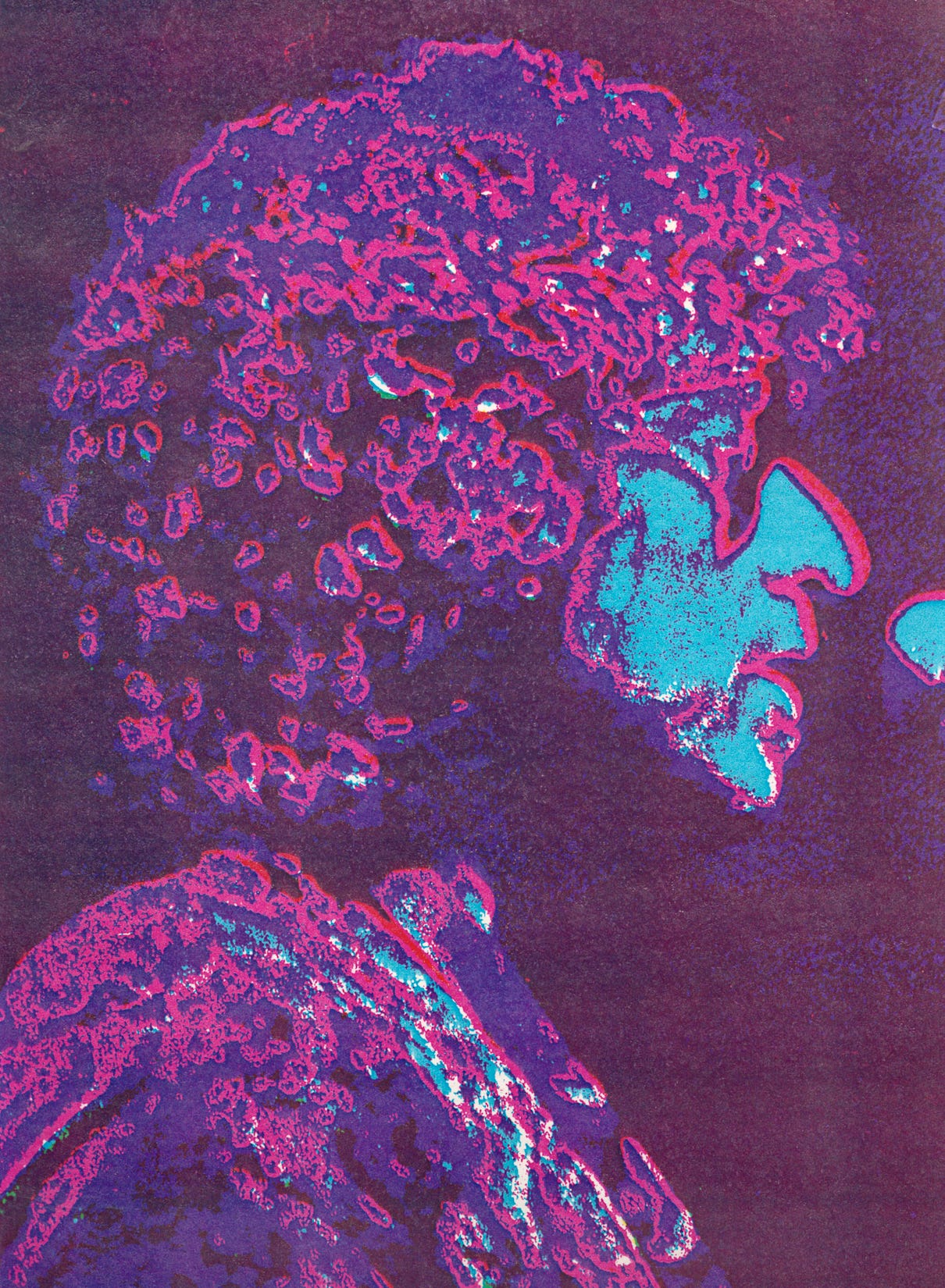

Blood on the Tracks came out 50 years ago today. For ages, I thought the cover image was a painting. Judging from chatter I’ve seen online, I’m not the only one. But it isn’t. It’s a photo, heavily manipulated, taken at the Toronto stop of Bob Dylan’s tour with The Band the year before (I noted it in the Toronto entry of my Tour ‘74 series last year).

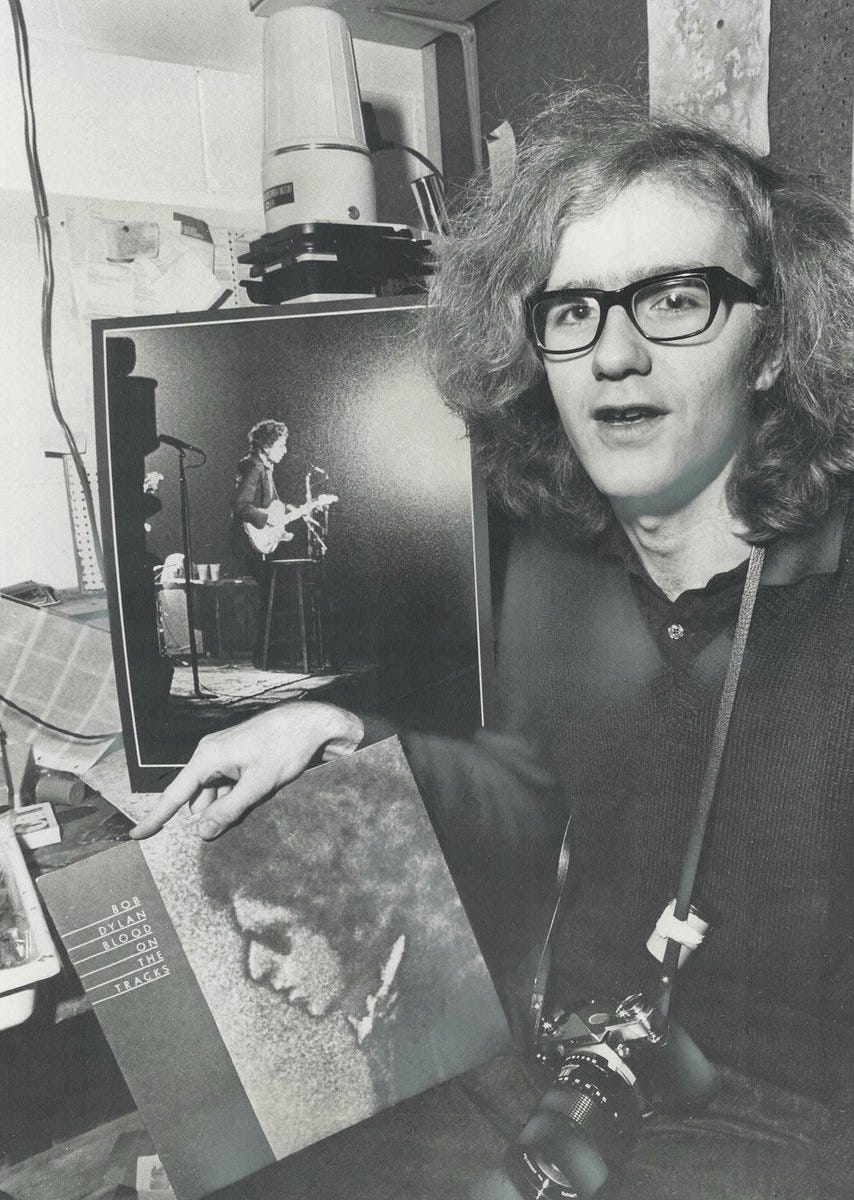

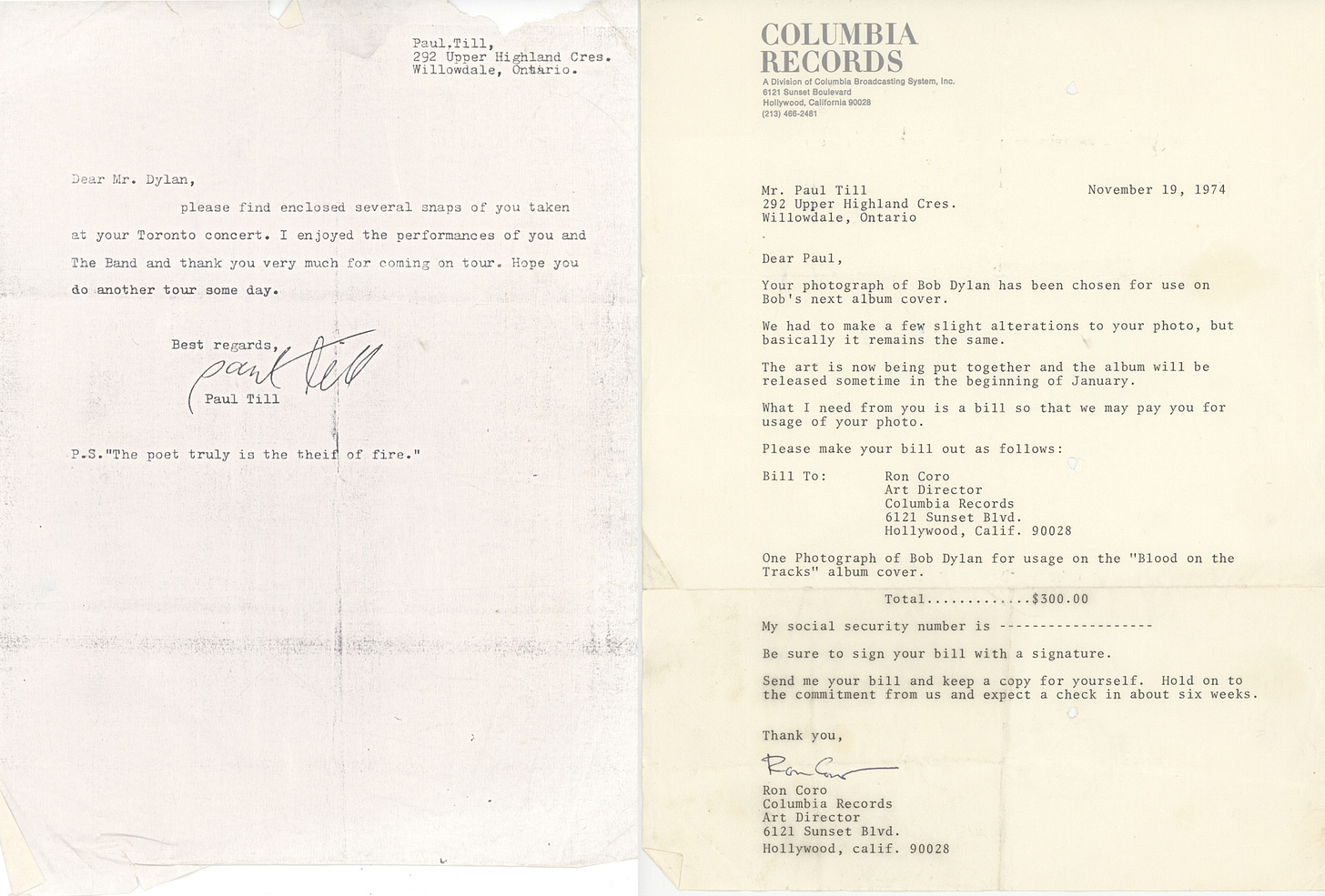

The photographer, and photo-manipulator, was Paul Till. At the time he was a 20-year-old college dropout who mailed the Dylan office his concert photo on a whim. Months later, he got a letter back. It began, “Dear Paul, Your photograph of Bob Dylan has been chosen for use on Bob’s next album cover…” (see actual letter below).

Today, 50 years later, Till shares on an in-depth look at how that photograph and album cover came about, and tells me about some other photos he’s taken of Dylan in concert over the years, several of which were also licensed for official Dylan products (songbooks, Bootleg Series installments, etc). He also shares some Dylan photos that haven’t been seen before.

To start with some context, where were you in your life in 1974?

In 1974, I was at loose ends. I’d gone to university for one year and dropped out. I was just working as a shipper at the Coach House Press, which was and is an incredibly great small press, and living with my parents. I would have been 20.

I had been doing some photography. I was very into dark room manipulation and solarizing and all that surrealist-influenced stuff.

The Blood on the Tracks cover came from the very first concert you ever shot.

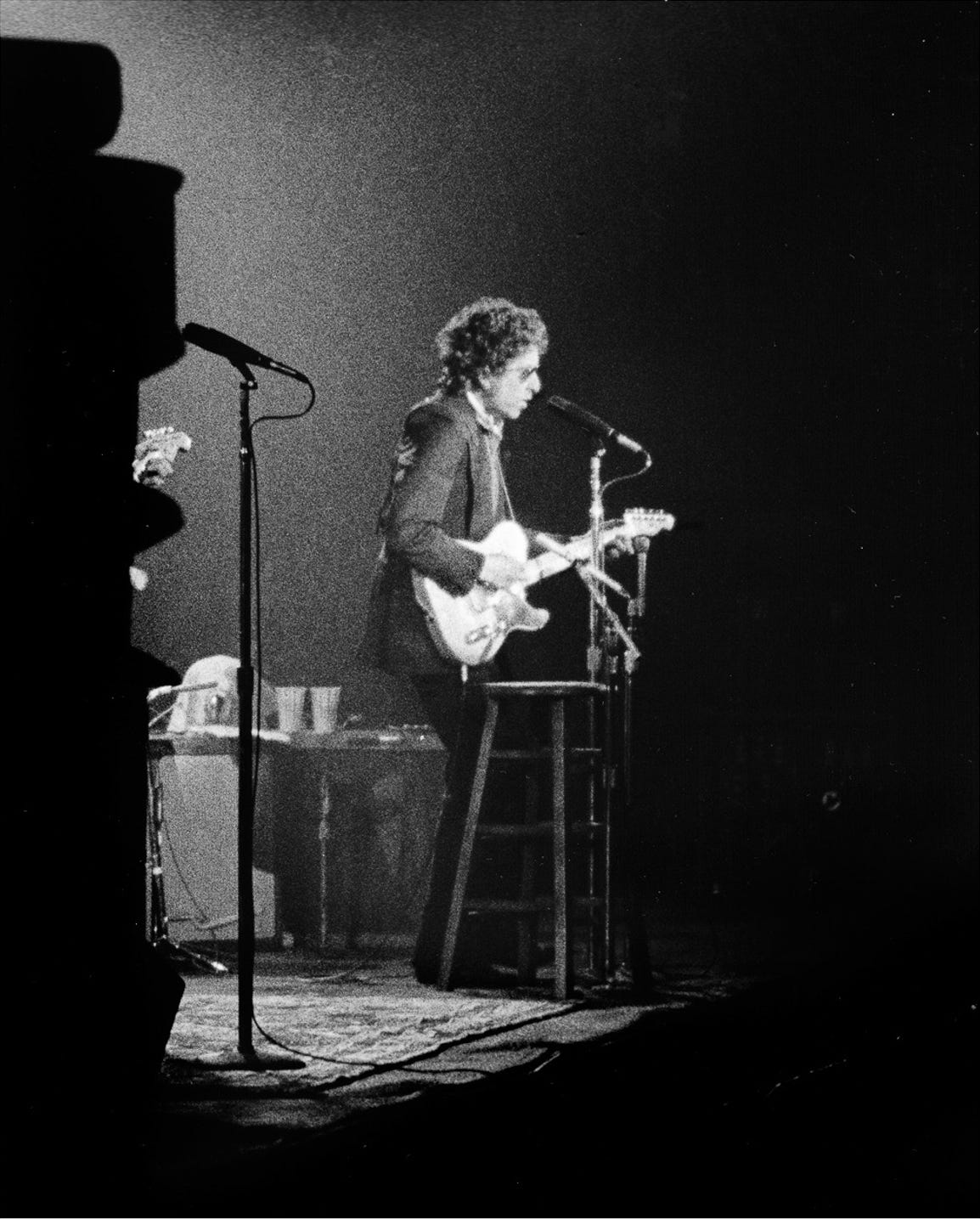

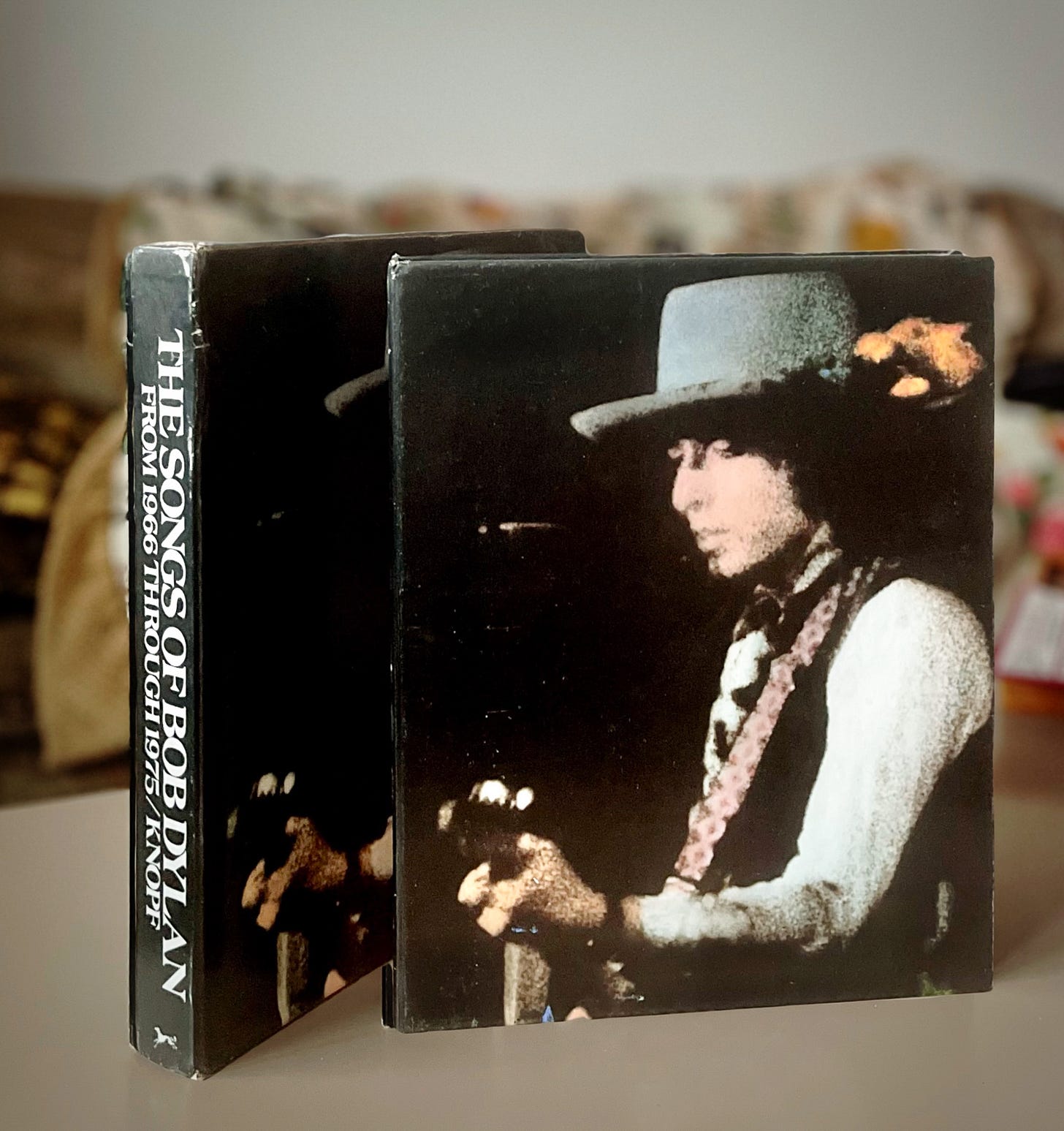

Yeah. I was a big Dylan fan. I’d never seen him, of course. They had a mail order thing for tickets. So I dropped my letter off at the post office, and I got relatively good seats. Not real close—maybe 75, 100 feet away. If you look at that image, the full figure one is still cropped a bit, and it’s a 135mm lens.

Did you have a photo pass, or did you have to sneak in the camera?

I thought you might have to, so I kind of did, but they weren’t checking. I put it underneath my coat anyway. I had a pre-war screw-mount Leica that my dad had used. I had a 50mm lens and I borrowed a 135mm from one of my sister’s friends father.

I just had a handheld light meter. If you’re not really close, it was terribly hard to get a good reading. You’ve got a spotlit figure against darkness and the meter gives you a reading from all of that. So I was kind of guessing. I really didn’t know.

So I was trying to focus when I was taking the pictures. The film was Kodak Tri X 400 film, which was the fastest (that is most sensitive, it needed less light) black and white at the time. You could ‘push it’—develop it longer, at the cost of some quality—to 1600. That shot, that’s really the only sharp one on the roll.

I printed it. That’s the one you see full frame, black and white. I used to always fool with dark room stuff, so I probably wanted to blow it up bigger, but I couldn’t really blow it very big with the enlarger I had. Do you know what an enlarger is?

I mean, I can kinda guess from the name, but not precisely.

It’s sort of like a slide projector. It’s got a head which contains a light, then a place that holds the film, and underneath that there’s a lens which focuses the image on the photo paper. You can make the prints larger or smaller by putting the head up and down. But not so far that I could get a big print of Dylan’s head from this negative.

So I was enlarging the image onto pieces of camera film such that it was just Dylan’s head and shoulders. The idea being when I developed that film and put it in the enlarger, I could make a print of just Dylan’s head. The first piece of film is a negative: what was light in the actual scene is now dark. When you print that onto a piece of photographic paper (or another piece of film) you get a positive. Then you can print it on another piece of film and get it back to negative, and then make the positive print from that.

I was fooling around with what’s called solarization, where, when it’s partially developed, you re-expose it to light. What happens is the parts that are clear in the negative are reversed and get dark, and then there is some reversal in the midtones. The ones that were already dark often don’t get affected. So you get a partial reversal, and you also get, between what was dark and what you made dark, some distinctive lines called Mackie lines.

Is this all how it gets the effects that it ends up having on the cover? Where a black and white concert photo looks almost like a painting, in color?

Yes. Plus I’d been doing hand coloring on black and white prints. It was a water-based coloring that was used a lot at the turn of the century. There is a company called Marshall’s, which made these photo dyes that penetrate into the emulsion. If you looked at the print after it’s dry, there’s nothing on top. The dye has gone right into the gelatine. The dyes are transparent, so they show up the most on light areas. You don’t get much effect on a really dark area.

Like how, on the cover, the most color is on his face.

That’s right. I made many different versions over the years. Working from the original negative and with new hand coloring, I made a digital version of the cover for the 40th anniversary. I tried to make it faithful to the album cover image, but a little better. Of course, me being me, I embellished some of those digital prints with pencil crayons.

Anyway, at the time, I made the print, and I mailed it to Dylan’s office. I wrote some very short note.

How would you have known where to mail it?

I went to the library, and there were these books called Who’s Who. They had everybody in there. It generally had an address for folks. It was a post office box in Cooper Station in New York. They still have a post office office box there.

What were you hoping for when you mailed it off?

I was sort of hoping for a letter back. I didn’t think, “Oh, it’s so great. It surely will get used.”

So after you’ve done all these manipulations and stuff, what you’re sending basically looks like how it looks on the cover?

Pretty much. They did something else, ‘cause I got a letter from the art director, Ron Coro. He said, “Your picture has been selected. There's been some retouching, but it’s basically what you sent.”

Who flipped it around, you or them?

Me. It was an accident. I just didn't notice.

So you get the letter from the art director, your photo is going to be used. What happens next?

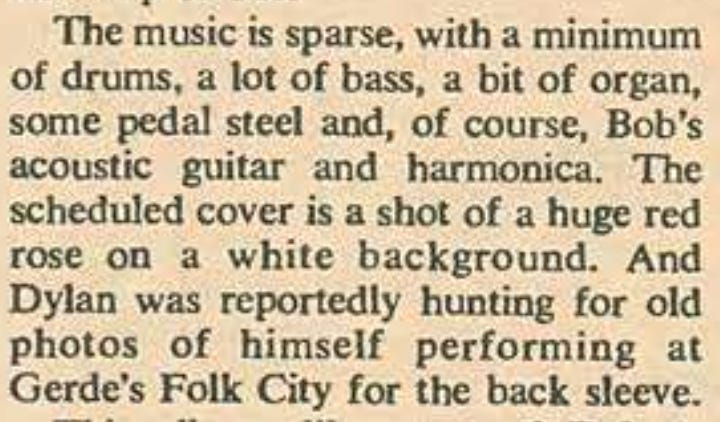

Well, the letter wasn’t entirely clear. I'd read something in Rolling Stone about the record being made and what was going to be on the cover, which was like a rose or something. I thought maybe my photo was on the back cover or something. But they said, “Please send an invoice for $300.” I sent an invoice for $300. I’m sure I could have gotten more.

Was the next time you hear about it when you see it in the record store?

In Canada, a lot of times the records came out a little bit later. I went to a specialized record store that had an import from the States. That’s when I got it.

Do you have any guess why they chose that photo for the cover?

I think Dylan saw it and wanted it. That’s my guess. Because, back then, it was not a big office. Naomi Saltzman ran it, and I think she had a few assistants. It wasn't like a big corporate thing. I suspect that anything of interest that came in was run by him.

Did you like the album?

Oh yeah. Because Planet Waves, which came out with the tour, I never thought it was mixed that well. It didn’t seem like The Band at their richest, in a sense of what they had been doing on their own or what they had done with Dylan on the tours and the Basement Tapes.

Speaking of The Band in ’74, it's sort of interesting that a photo from this 1974 tour, which sounds so totally different than Blood on the Tracks, gets used on the cover.

That’s right. It was serendipity that my photograph does work with the record. Like it’s appropriate for that record.

Were you at the first or second night?

Second night. One of the few times they played “As I Went Out One Morning.”

The only time.

They also played “I Don’t Believe You,” which they didn’t play the night before. I was pleased to hear that one.

I’m sure an impossible question, but I’ll ask anyway. You don’t have any guess of what song he was playing when you took that photo?

No. I mean, I was trying to balance out taking the photographs and listening to the concert. It was clearly taken during a set with The Band. There are some pictures I took with a 50mm lens where you can see more of The Band. They're not especially sharp or good.

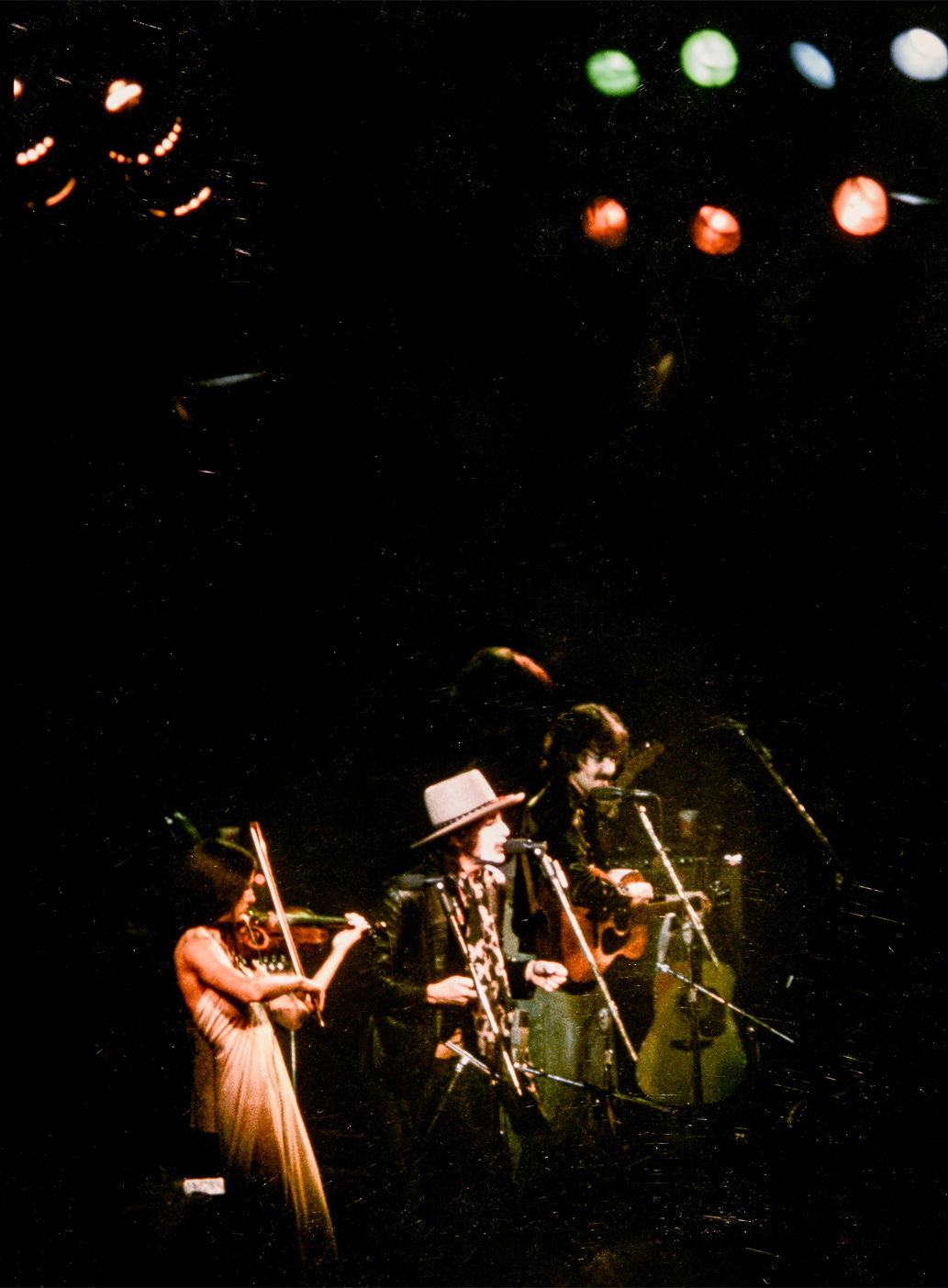

Let’s move ahead a bit and talk Rolling Thunder. You shot two Rolling Thunder shows. One photo was used on that songbook. Was that a similar story, where you had done the various manipulations yourself and sent it off looking like how it came out?

Totally. I mean, it worked once! The publisher wrote back. I was a bit smarter. I think they offered five hundred, and I said, “I think I’d like 750.” I got it.

What was that book anyway? I’ve never seen it.

It was a hardcover songbook with the chords, the piano parts, etc. It’s 1966 through 1975. The first songs are Blonde on Blonde songs.

By the time of the Rolling Thunder Revue, I was now in the first year of photography at a community college. With the Blood on the Tracks cover, I thought maybe I should do this for a living. I had a little bit more equipment, and I took it all to the show. I had two cameras: The Leica with the 50mm lens and an Olympus OM1 with a 50 and a 135.

Once again, you can just walk in with this stuff and no one’s giving you trouble?

No. We got there, and you couldn’t take cameras in! That was a surprise.

It was cold; I had a big winter jacket. I stuffed them in my jacket pocket and put gloves and stuff overtop. I remember the security guard saying, “What do you got in there? A camera?” I said, “No…” I guess at the time they didn't really have the authority to make you take the stuff out of your pocket. So I got it in.

Now I’m pretty nervous and I was pretty far back on the floor. Then my friend Tony Hine came up and dragged me closer, past some low-key ushers. We still weren't really that close. The second camera, the Olympus with the 135mm lens, it’s that roll that the songbook cover came from.

Again, I used darkroom techniques to improve photos that were marginal technically. You can separate details that are important, like say dark hair against a black background, so that they would show up. Sort of what you do with Photoshop now.

Then you photographed a second Rolling Thunder show a month later.

That time we knew you couldn’t take cameras in. Tony put the camera body under his jacket and he put the long telephoto lens in a box of Pringles. He put some Pringles on top and he showed them to the guy. “Look, they’re Pringles!” I don’t know that I would have had the nerve to do that.

He took some photos, and I took photos. There’s a kind of a nice one of “Isis” where Bob’s throwing the fists. No guitar. There’s a nice green light shining down. I think I took that one, but who knows.

I did a bunch of color manipulations on those ones, and I sent them off. I did the same with the photos from the Gospel tour in 1980. At some point I got “Thank you, they’re nice, but we’ve already picked the pictures for his next record.”

I tried it a few more times. I mean, it worked twice! For the 17 cents the stamp cost, it was an excellent bet. It’s very long odds that something good might happen, but there’s no big risk to it.

After that, I photographed the ’78 tour. I pulled one image out of that. I had a bigger lens, but I was much further away.

That photo is wild. It’s extremely manipulated.

That’s a long lens, blown up, from really far away. I was sort of timid; I probably could have moved around more. Or maybe not; it was a hockey arena, the ushers kinda control where you go.

And then I photographed the gospel tour. I’m less vociferous about now it than I was then, but I was an atheist. I was like, “Oh my God!” I mean, he said some pretty stupid things at that concert, you know? He was going on about the Middle East and End Times stuff. I hadn’t liked the record much, though I liked gospel music. But I went.

I had actually phoned Massey Hall to ask if you were allowed to bring a camera, and they said, “Well, we haven’t heard anything.” So I had this big long lens and got pretty close. I felt free to wander because I didn’t like the songs; I wasn’t missing anything. It was pretty genteel. These were professional ushers in uniforms and stuff. They're not security people.

I got things where I didn’t have to do that much work later to pull something out. They’re straight prints.

I did do some manipulations of the color. He had a leather jacket, so he looked very 1960s. At the end, he was like out there singing and everyone was down in front near him.

One’s very red.

I've always experimented with techniques. I was very much into darkroom stuff at that point.

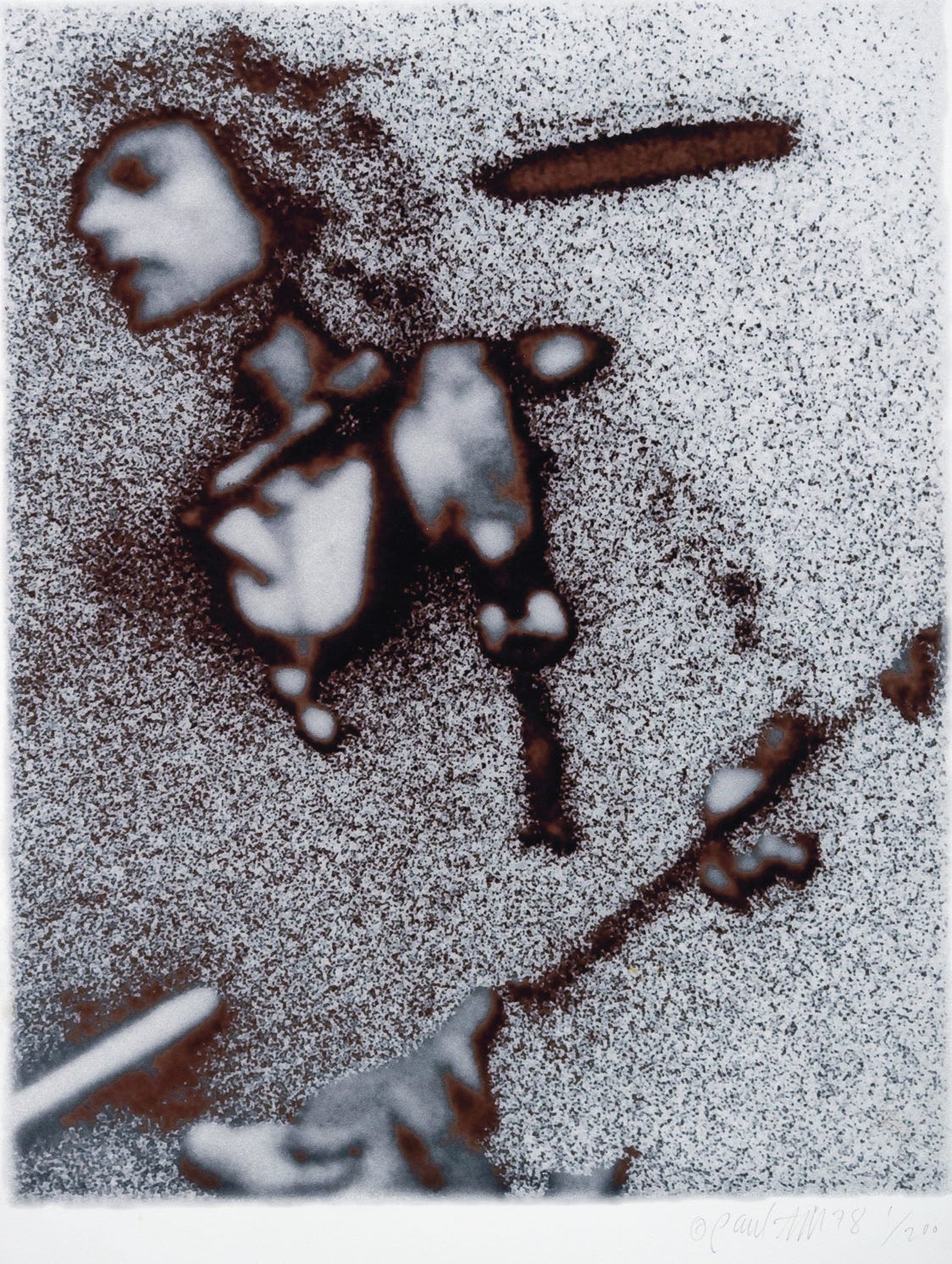

Tell me about the next one, ’81. That's one of my favourite highly-manipulated photos.

You were allowed to bring cameras again. And, again, I wasn’t very aggressive. It basically looks like the Blood on the Tracks one, except it’s not flipped.

They were all kind of like that. It’s a continuous tone negative. I generate tone separations, which means it’s just black and white. So you can really take any area and make it any tone—darker or lighter. Then you have a bunch of different negatives that are like positive or negative, solarized or not. So, I had all those, and then you put them together in different combinations.

I made the actual print with the first color Xerox machine, which was a very clunky thing. It was a three-color machine, and it made three passes, one for each color. So you could put three different prints on it. You could slide one out and put in another. I would put different ones on for the different passes so you get all these different color combinations.

We’re skipping a lot of years before the next photo, but in the middle of that, I gotta hear the story of how you became an extra on Hearts of Fire.

A friend of mine, Malcolm Glassford, was working on Hearts of Fire. They were filming mostly in Hamilton, an industrial steel town outside Toronto. He said, “I can get you on as an extra as a photographer, and you can bring your own camera.”

I didn’t know if Dylan was going to be in these scenes or not. He wasn't. They had a Lear jet at the Hamilton airport. Rupert Everett and Fiona come out, and I’m in the mob of photographers. I remember it was really cold. I had a trench coat on with so much clothing underneath, because the scene wasn’t supposed to be set in the winter.

So you were actually shooting photos? Even when you were being an extra.

Yeah, I was shooting. The movie folks said “Great, you’ve brought your own camera!” But I never saw Dylan there.

They did film a concert in a warehouse later, and we went to that; we were part of the concert audience. Mostly it was just messing around. I think Dylan just did one instrumental jam. I couldn’t have got much of a camera in there, though in retrospect I wish I had tried.

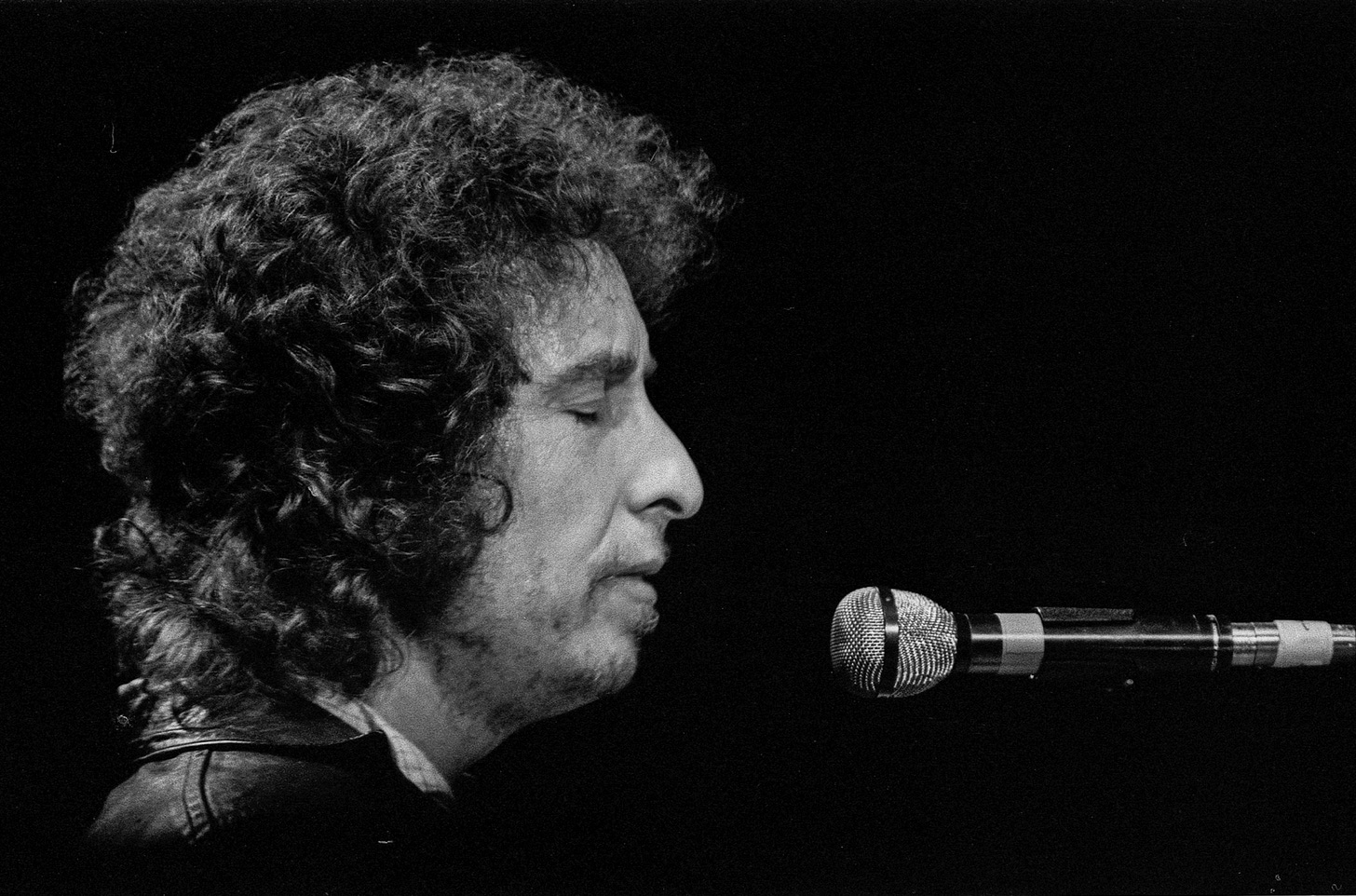

We have two more recent photos to talk about. One from Massey Hall 2014.

I was at the O’Keefe in 1990. He played three nights. It was great, all different songs, Ronnie Hawkins guested. But I didn’t try and take a camera in. I remember Dylan was pointing at somebody. I thought it was like some performers pointing to the audience as an acknowledgement. No. He was pointing at a guy that had a camera for security to go get them.

So I never took a film camera again. It was too obvious. It didn’t seem like it was worth it. But then digital came along. And they’re small cameras.

For the ’14 show, I got great seats in the second row. But they have their people looking for cameras. It’s not the Massey Hall ushers, who are only going to scold you and tell you to put it away. There was somebody sitting there looking outwards from the stage. I had this little camera and what I was doing is, I would lean forward onto the back of the seat with my hands together under my chin, so I could hide the camera under my hands, I couldn’t look through it. It was auto-exposure and you’re not having any control over it. So it didn’t really work out that well. This was the best shot I got, and it’s not very good. And that’s after a lot of work on it.

Then the one in Barrie [Ontario] in 2017. I brought a bunch of cameras in my car. It’s a smaller town about an hour north. Security was not especially tight. When I got in, I was a bit mad, because I’d got nervous. I’d taken a smaller camera than I probably could have got in.

We were back around the 10th row or something. If you took it out, security would come and tell you to put it away. They wouldn’t do more than that. Mostly Bob was behind the piano. But at certain points he did get up where you could see him. So I got a few shots and I had to take two or three and put them together. The hair was better on one, stuff like that. But I think it looks cool.

Are you using Photoshop now or is this still the old school darkroom?

Photoshop. I’ve been shooting digital for 20 years, and it’s all Photoshop now. Mostly putting stuff together, increasing the sharpness. In a sense it’s the same process as I did with Blood on the Tracks and the other ones. I’m pulling all of the useful information out and emphasizing it.

This last one is full circle because it kind of looks like Blood on the Tracks. He’s facing the same way; it’s got that heavy manipulation.

It's very similar. I felt it was a “lion in winter” kind of image.

Thanks Paul! See more of his live concert photos and other work at PaulTill.com and RockandRollPortfolio.com (you can buy prints there too, including of the ‘Blood on the Tracks’ cover shot).

Another great article. Wow, what a thing, to get a letter saying Bob wants to use your photo. For Blood on the Tracks! And then it becomes absolutely iconic.

As a 15 year old in 1975, I thought that cover was magic. Still think so.

Also, very cool interview in Rolling Stone! But come on Ray, you’re a huge Bob Dylan fan and you’re completely uninterested in the words?!? I don’t believe you! Not sayin you’re a liar but …

Crazy amazing story! What luck Paul Till had! I'm surprised that after having had 3 of his photos used he didn't appeal to Bob's office for a photo pass for future shows! What a fairy tale, so good! And I dig Toronto's Coach House Press too - they've put out some cool books!

You guys didn't get into what Paul is up to now, and if photography is still just a hobby or if he's made a career of it.

Another great one, Ray!