Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Click the button below to get new entries delivered straight to your inbox. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only.

Update June 2023: This interview is included along with 40+ others in my new book ‘Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members.’ Buy it now in hardcover, paperback, or ebook!

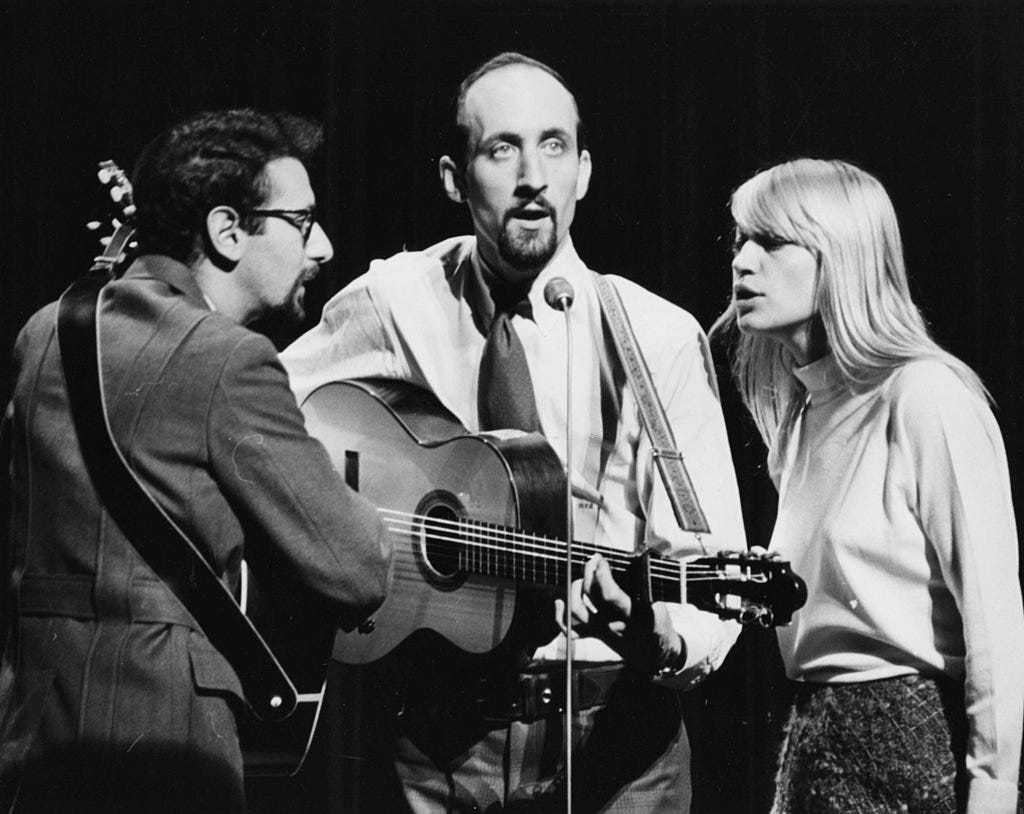

Noel Stookey is best-known by his middle name: Paul. That’s “Paul” as in the iconic musical trio Peter, Paul, & Mary. They first found success in the ‘60s folk music boom — and, along the way, helped a certain young songwriter with an acquired-taste voice reach a broader audience. Their “Blowin’ in the Wind” was the first recording of a Dylan song to top a Billboard chart (Bob wouldn’t top a chart with his own recording until “Murder Most Foul” in 2020).

Six decades on, Stookey’s still going strong pursuing both music and activism. On the music front, he released his latest album Fazz earlier this year, fusing folk and jazz (hence the title). And on the activism front, he co-founded the nonprofit Music to Life with his daughter Elizabeth Stookey Sunde. Over the summer, Music to Life received a $500,000 grant from the Mellon Foundation to train musicians across all geographies, genres and generations in social-justice work. Interested musicians can join Music to Life’s mailing list for more information on the 2023 program.

“These artists are activists, really,” he explains. “This is not just holding a benefit dinner where somebody gets up and sings a song, and we donate $100 to move it along. I fall into the camp of the guy who's called to do the benefit, but these activists that Music to Life supports actually go into the community, from the prisons of Maine to the homeless of Houston. There's an element of hands-on participation that wasn't there in the '60s.”

When I called Stookey up recently, we, naturally, mostly talked Dylan. That means the heady days of Greenwich Village in the ‘60s, of course, but also when he spent time with Bob and The Band up in Woodstock after the motorcycle accident, and also several later run-ins in the ‘80s.

It's an auspicious day for us to be talking, the day after Joni Mitchell’s big return to Newport.

That's lovely. I never paid too much attention to Joni's work, but, I kept hearing Judy Collin's versions of her work. I was rather closer to Judy than I was to Joni.

There's an obvious parallel there maybe, with Dylan versus Peter, Paul & Mary, in terms of one artist helping popularize another.

Yeah, but the Dylan-Peter, Paul & Mary thing was really a natural evolution. When people credit Peter, Paul & Mary with introducing Bob Dylan, I understand it on one hand. On the other hand, I really feel it was inevitable because of the power of the lyrics. The nature of the lyric, and the fact that it was talking about something which was so contemporary, was changing the face of popular music in the ‘60s, and arguably, continued on into the formation of folk-rock in the '70s.

I think inevitably Dylan, regardless of the voice, would have become very popular. Albeit he leaned into it perhaps a bit theatrically, that voice had a certain kind of authenticity to it that people couldn't deny. You wouldn't go public with a voice like that unless you really meant it. [laughs]

Do you remember your first time encountering him, I assume in one of the Village clubs?

I was the master of ceremonies and a performer at The Gaslight. I was really not a folkie as much. I had so many hats I wore, honestly. I was not only the master of ceremonies, but I was the maître d' from time to time. I was the program originator. The Gaslight was slowly evolving as the premier spot for folk singers to show up. Of course, there was Mike Porco's place, Folk City, but The Gaslight was like the place where Len Chandler, Dave Van Ronk, Tom Paxton hung out.

One night, in through the door comes Bob Dylan. I say, "Yeah, we have our open mic, we can get you up." The first time he was there, and I don't remember the year, but it was probably '60, he sang mostly derivatives. Nothing original that I can recall. Honestly, he was in and out.

He came back about a month later, after working a chess club in New Jersey, and asked if he could go on. I recognized him and said sure. Knowing ostensibly what kind of music he was going to do, I segued him in between a flamenco guitar player and my own comedy routine.

He got on stage and began to do a folk song called “Buffalo Skinners.” It tells the story of a man who’s out west. He gets a job working for a group of people skinning buffalo hides. At the end of the season, he wants to move on. He goes to payroll, and they pay him in buffalo skins. He says, "What am I supposed to do with these?" The guy says, "Oh, just take them to the general store and trade them off." So he goes to the general store, and he gets supplies for his trip further west.

Well, Dylan starts singing this song that has those same chords. Only this is the story about a folk singer who works at a chess club in New Jersey. At the end of the gig, the proprietor pays him in chess pieces. Dylan says, "What am I supposed to do with these?" "Just take them to the bartender. They're like currency." So Dylan goes, sits at the bar, orders a beer, pays with the king, and gets two rooks in change. [laughs]

That blew my mind. In retrospect, it is obvious to me that Dylan had a sense of what folk music was. That its reach was much broader than the specific story. That it could communicate concepts borrowing on tried and true traditional forms. Shortly after that, I recommended him to Albert Grossman, who was Peter, Paul & Mary’s manager. It wasn't too long after that Dylan became part of his stable.

To carry this story further, maybe a year later Albert shows up at The Gate of Horn in Chicago, where Peter, Mary, and I are on the bill with Shel Silverstein, and plays an acetate of two songs that he felt we might enjoy. One of them was “Don't Think Twice, It's All Right” and the other one was “Blowin' in the Wind.” Needless to say, both of those songs became hinge points for Bobby.

I think we were just coming off “If I Had A Hammer.” It was introducing the concept of music with a message to what had been a popular music format. That's when disc jockeys could still make decisions about the music that they wanted to play, whether it was Buck Herring who would play “Lemon Tree,” our first single hit, or whether it was a raft of increasingly socially-minded disc jockeys like Dave Dixon out of Detroit. The music that spoke to a social conscience began to take over the airwaves.

What about those two songs, “Blowin’” and “Don’t Think Twice,” made them seem like potential Peter, Paul & Mary songs? Obviously they're not being delivered to you in three-part harmony.

We always took a song for its value, not really the performance of the artist who created it or brought it to us. We knew we could do just about anything we wanted to, because we had three very individual voices. The first song we ever did was “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” because the three of us had such different versions of all the other folk songs, it was the only one we could agree on.

There was such a natural feel between our voices that no matter who had the lead, the other two would find parts. I think stylistically what Peter, Mary and I were able to do was to accent the meaning of the song. We always made our decisions based on what said the lyric best. If that meant somebody had a solo line, then they had a solo line. If the meaning of the lyric was better advanced by a duet, then we would do it in duet.

How did that express in the lyrics of, say, “Blowin' in the Wind”? Can you think of any examples of certain lyrics pointing you in certain directions?

“Blowin' in the Wind” is like an accumulated wisdom, so it was an accumulated vocal. The first line would be delivered as a solo. Second line would be a duet. Third line would be together. The chorus would be in harmony. Then a different person might take a lead on the next verse and be joined a line later by somebody. In a sense, it built. It satisfied our desire to emulate what the song was trying to say, that together we should pay attention to these things. I don't even know if we were that calculated, but it seemed intuitively the right direction to go.

We would make decisions like that all the time. I have a new album out called Fazz, which was a term that I incorporated after hearing Paul Desmond try to describe a song that Peter, Paul, and Mary and Dave Brubeck Quartet were going to do together. Kind of a marriage of folk music and jazz.

In the release of this album, I looked back at a lot of songs that I'd done in the Peter, Paul & Mary era. I was introducing a lot of alternative jazz chords into the folk milieu. At one point, Peter caught me doing a major seventh chord behind a Woody Guthrie tune. He said, "You don't play major sevenths for Woody!” Although it struck me at the time as kind of arbitrary, it underlines what I was telling you, that the ultimate decider of whether something should be incorporated in a song, whether it was a vocal or a guitar chord, was what the song was saying. Does this enhance the song or does it detract from the message? Stuck with those stark decisions, life became easier. It might be clever musically, might even sound pretty, but if the song's not supposed to sound pretty for that particular lyric, then don't put it in.

In those early days, are you running into Dylan every couple of weeks in various coffee houses and clubs? What's the scene like?

We were all aware that there was a lot of interest in the music that we were doing. For a period, as long as you were in New York, Greenwich Village was where you were.

Pretty intensely for about three months, maybe even as long as six months, during the rehearsal period of PP&M I remember we'd hear Bobby at any one of the coffee houses. Performers, as a rule, went from one coffee house to another. Not for employment, but just because they had friends at the other coffee house who would call them up on stage to do a guest set.

There was a great interplay between the Figaro, the Bitter End, the Gaslight, the Rienzi, and Gerde’s Folk City. There was a great deal of informational exchange. As a matter of fact, somebody told me that Odetta once played a song on stage with her back to the audience because she didn't want a person that she knew was out in front, a competitive folk singer, to steal her chords.

This was just prior to Peter, Paul and Mary beginning to move into clubs like The Blue Angel a little uptown, ‘bringing the music of the common man to the sophisticated elite’ [said with a touch of sarcasm], and then going out on the road. That changed everything. Once you went out on the road, you would stop by The Gaslight to hear somebody who was happening, but that scene went away pretty quickly. By the time we came back to the Village, everything had gone upscale. That folk explosion was over very quickly.

When you got impressed with him as a songwriter, what was he like as a performer, as an onstage presence?

He was probably nervous, because he was just so introspective. He was very tight-lipped. He was not comfortable. I would say that social graces were not high on his skill list.

What do you mean?

Weak handshakes, mumbled hellos, odd introductions to tunes. I'm not a psychiatrist, but it seems like his natural inclination is to be a loner and quiet. Even though his talent was drawing him to the stage, it was not his most comfortable place to be.

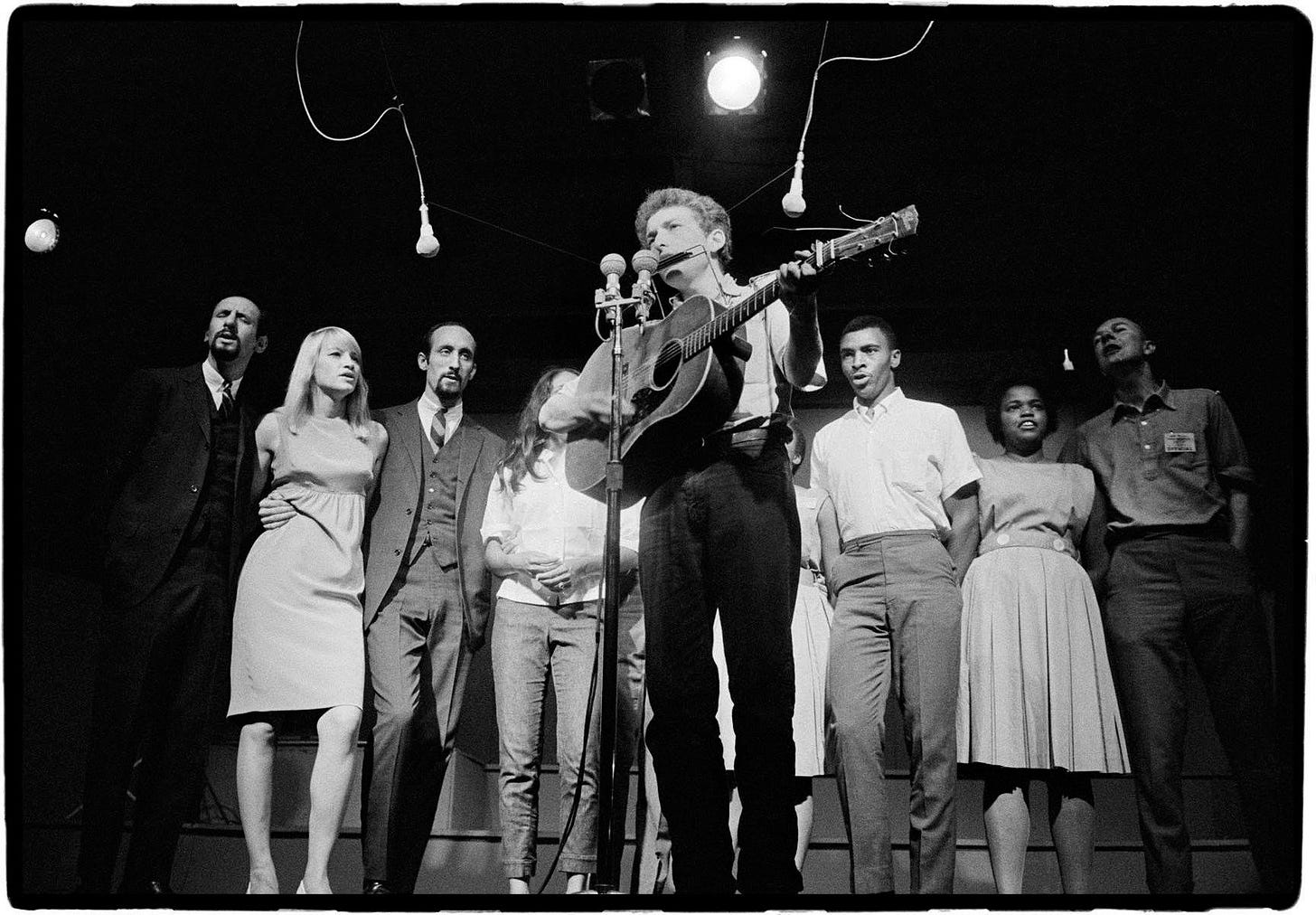

In 1963, you all and Dylan both sang at March on Washington. I've seen the videos of the music, and I've seen the videos of King, but can you put it all together, explain what the role of musicians was that day?

Music was such an important part of the movement. Whether it was The Freedom Singers, whether it was people singing during the marches in Selma, any circumstance that occurred where Civil Rights was being talked about, there was music. Maybe because Pete and “We Shall Overcome” was so much a part of it. Maybe because it’s part of folk music's calling to be this connection between human life and the arts. Even the rehearsal that took place in front of the Washington monument integrated music, between Odetta singing, Dylan and Baez singing, us singing, in between the speeches. And then we all marched to the Lincoln Memorial.

Music spoke on a couple of levels, but what it did was focus us on the interconnectivity of all people. When you sing together, you are connected in a way that standing shoulder to shoulder listening to someone speak doesn't do it. That was an important part, and still is an important part, of understanding that we're all in this together.

Also in the summer of 1963 was Dylan’s first Newport. Elijah Wald’s book mentions a private plane that Grossman put his clients on that flew you three and Dylan to Rhode Island. Does that ring a bell?

At that time, Peter, Paul and Mary were doing college campuses. We bought a Lockheed Lodestar. Peter used to call it the lobster load-hard. We had three tail fins like the old TWA planes. It really helped a lot because then you could fly from campus to campus, small airport to small airport. You didn't have to do transfers, all of that. It was that plane, I think, that you're referring to. It ultimately had one of Dylan's guitars in the back cupboard, as I recall. It may have even been the one that he played electric on in Newport.

Most people denigrated his move from what was viewed as political writing into introspective writing. Phil Ochs, particularly. But as far as I was concerned, that paralleled understanding in my own life. You could talk about politics, but it all got down to being individually responsible. And if you're going to be individually responsible, you got to figure out who you are. I thought Dylan's change was a very natural one, and I think part of an evolution that I mirrored myself when I went spiritual in the late '60s. I don't think he relinquished his concern for the human state; I think he just broadened it, and people weren't ready for that.

Two songs I saw brief mentions of interesting stories and I wondered if you could expound. The first is “Talkin' Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues.” You gave Dylan the article that inspired it?

That was right after his rewrite of “Buffalo Skinners,” a day or two days later. Bobby was still in town, still coming to The Gaslight to sing. I was so impressed with what he had done that, when I saw the article, I thought, this guy can translate anything into a commonly understood circumstance. I brought him the newspaper, as I recall. I just handed him the whole clipping. He came back, I swear it was the next night. There might have been a day in between, but he came back very quickly and just did “Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues.”

So you had given it to him with the idea that there's a song in this story and he could probably write it?

Yes, that there was a Bob Dylan song.

What about that newspaper story do you think lent itself to that?

The incongruity. I think Dylan saw incongruity and was able to comment on it handsomely. He could give it a full effect. In the song, don't some people end up washed on shore? I’m not sure that actually happened, but the boat did capsize. His ability to give it bone and structure was pretty amazing. I knew he would, just from the “Buffalo Skinners” tune.

And what is the story behind another talkin’ blues, your own “Talkin' Candy Bar Blues.” I read Dylan contributed to that, but his verse did not end up on the album. What happened there?

Actually, Dylan I don't think contributed— Oh, yeah you're right! Wow, your research is great. [laughs] Now that you mention it, I had written the “Talkin' Candy Bar Blues,” and Albert sent it to Bobby because he liked the concept, but he wasn't sure where the song was going to go.

So it was a work in progress?

It wasn't finished when Bobby saw it. Bobby came back with something that was very stiff. Which surprised me. Or it may not have been stiff; I just may have had my back up.

I'm glad where the tune went, but it didn't use any of Dylan's things. I think he introduced some community concepts that were not neighborhood. They were just…I don't remember. I think he tried two or three verses and they just didn’t sit right with me. Gah, wouldn't I love to find somewhere in my archives, that original contribution by Dylan? Thanks for reminding me of that.

Do you have much of an archive? Are you a person who is collecting stuff, hanging onto stuff?

What do you mean, pack rat?

Ha, yeah sure. Pack rat.

Well, honestly, yeah. It’s like where my wife looks at my workshop downstairs and the stuff that I said, "Oh, don't throw that away, I'll fix it." It’s a meager 10% that eventually makes it back up the stairs. I'm looking at my archives the same way.

Now, to a certain extent I'm responsible for the Peter, Paul, and Mary archives as well because I've got a humidity-controlled room downstairs here in Maine. So I've got a lot of the audio and video tapes, master tapes from all the work that we've done. I'm about to actively employ an archivist to help me go through it.

Have you been in touch with the Bob Dylan archive down in Tulsa? Have they reached out to you?

Yeah, there's some talk, but I think they go through Peter more. We did get a request from the Kentucky Music Hall of Fame to put up a kiosk for Mary. We're assembling some photos and some letters, archival stuff, even some costuming that we'll probably send down to them. In terms of the Dylan thing, I'm not sure the degree to which Peter, Paul, and Mary are going to be incorporated.

In terms of actually staying in touch with Dylan later on, our paths crossed a couple of times. We saw him backstage at some television show [a Martin Luther King tribute in 1986] where he butchered lead guitar on “Blowin' in the Wind” with us and Stevie Wonder. It was one of those mishmashes where the producer says, "Oh my gosh, we can get all those names together on the screen, we'll have a sell-out TV show." So they put Dylan and us and Stevie together to do “Blowin' in the Wind” and it was not very good.

Backstage Dylan said, "Are you still with the Lord?" I said, "Oh, yes."

That really came about because of the trip that I made up to Woodstock following his accident. He was going through some changes himself. That was just before he put out John Wesley Harding, and of course, several years before his two reborn albums.

He asked me to do a bit part in a film he was doing in Woodstock around the time of the motorcycle accident.

Do you remember what your bit part was in that Woodstock thing?

Yeah, I was dressed in a white monk's robe. It was outside in some forest someplace, but I'm sure that what I saw mostly was the cutting room floor.

What were you doing in your white monk's robe?

I think I was pontificating. This would've been prior to either of our spiritual experiences.

Just like a solo clip or with The Band or Bob?

No, solo. I think Howard Alk was the cameraman.

Did you see any of the shows on the post-Newport tours with The Band?

I think by that time, I was really not paying too much attention to what Bobby was up to, or if it was, it was sporadic.

Peter, Paul & Mary didn't have to contend with a purist criterion. We had already gotten criticized a couple of times as being slick. We just stayed with our acoustic instruments. Though our harmonies were maybe challenging to those who just love Appalachian music, we pretty much did the music we wanted to do. Borrowed from folk artists, changed harmonies sometimes. We wrote a bridge to Phil Ochs’ “There But for Fortune.” Who's audacious enough to do that? That was all part of our comfort zone. If we felt it needed to be done, then we did it, and hang the fallout.

What I'm saying is, we were caught up in our own world, especially through '69. Then we took six years off for what we fondly refer to as good behavior and didn't get back together again until ‘78.

If you're doing your own thing after Newport and all, how do you end up in Woodstock doing the little film thing?

Spiritual search. Suspecting that reality is not all it's cracked up to be. Looking for some soul direction. Also, the advent of the Beatles, because that was pretty powerful. That was an arrival on the pop music scene at least as cataclysmic as folk music's arrival was. And really in a direction of self-discovery. A lot of the Beatles tunes were, after you got past “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” self-discovery.

That was the big question I put to Bobby, "Have you heard the Beatles? What does that make you want to do as an artist?" That's when Bob said to me, "Well, you got to hear my new album." As if John Wesley Harding was his answer to the Beatles. I thought that was curious because, certainly, stylistically it wasn't.

Are you around at any of the Basement Tapes stuff? Where are you having these conversations with Dylan?

Maybe I had one dinner with The Band and Albert at the restaurant he used to own in Woodstock. That was it. I had a bass player who got married in Woodstock, Jim Mason, who went on to produce Firefall.

I'm guessing this relates to Albert too, how does “Too Much of Nothing,” this basement tape song, make its way to you guys to perform?

I can't remember. Probably Albert again and/or his ongoing relationship with Peter. I know we did a very pop version of it.

Years later, you guys were on the same bill again at Live Aid, right?

That was not a happy scene, particularly for Mary. The expectation was that we would go on and sing “Blowin' in the Wind” with Bobby to conclude. When he called up Keith Richards and Ron Wood, it just…I don't know. I think it permanently drew a line between who Dylan thought he was and what Mary thought the folk community should be.

I just remember going over to Dylan's trailer, him sitting on the steps. The assumption was we were going to go on stage later with him, and we never did. We did go for the big finale, but that's all. We never sang at Live Aid ourselves. That was not a good feeling.

Basically you were only there to sing with Dylan and then he snubbed you.

Uh huh. Like I said, social skills were not high on Bobby’s skill list.

Well his team up with Keith Richards and Ron Wood, I think these days, most Dylan fans consider that about the worst performance of his career.

Yes, even Dylan might agree. I just saw a clip of it recently. Either Ron Wood's guitar went out, or somebody's guitar was not in tune, so they kept shifting off guitars. Nobody else sang really except for Dylan.

To try to draw some value out of that experience, I would have to say, I think what he was trying to do was to reach across predispositions. I really do. He was trying to say, "Hey, we're all in this together. Even people that you don't expect are in this together are in this together." I would have to give him the benefit of that statement. I don't think he was doing it for self-glorification. He didn't need that. I don't think he did it because he was buddies with those guys. I think he did it to make a broader statement.

That was about it. I haven't heard from Bobby or spoken to him, it's got to be 40 years now. If I was going to encapsulate it, I'd say that we had an affectionate but distant relationship. I think it was really super what he wrote on the Peter, Paul & Mary liner notes about me doing my Charlie Chaplin imitations with flickering lights in The Gaslight. He did have a poetic sense that he could put on paper without music from time to time.

Paul then was a guitar player singer comedian-

But not the funny ha ha kind-

His funnyness could only be defined an described by the word

"hip" or "hyp"-

A combination a Charlie Chaplin Jonathan Winters and Peter Lorre-

Maybe it was that nite that somebody flicked a piece a card-

board in fron a the tiny spotlight an he made quick jerky

movements on the stage and everybody's eyes was seein first

hand a silent movie for real-

The bearded villan 'f an out a print picture-

There aint room enuff on the paper t tell about everybody

that was there an exactly what they did-

Every nite was a true high degree novel-

Anyway it was one a these nites when Paul said

"Yuh gotta now hear me an Peter an Mary sing"

Mary's hair was down almost t her waist then-

An Peter's beard was only about half grown-

An the Gaslight stage was smaller

An the song they sung was younger-

But the walls shook

An everybody smiled-

An everybody felt good-

Thanks Noel! Learn more about his current social justice work at Music to Life and more about his new album Fazz at his website.

Update June 2023:

Buy my book Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members, containing this interview and dozens more, now!

I enjoy your deeper than Heylin interviews. Thanks for describing the subtleties and backstories of Dylan's relentless creativity. I'd love to hear from Duke Robillard and his Time Out of Mind studio and tour experiences.

Maybe it's just me but that MLK appearance is great! Thanks for sharing.