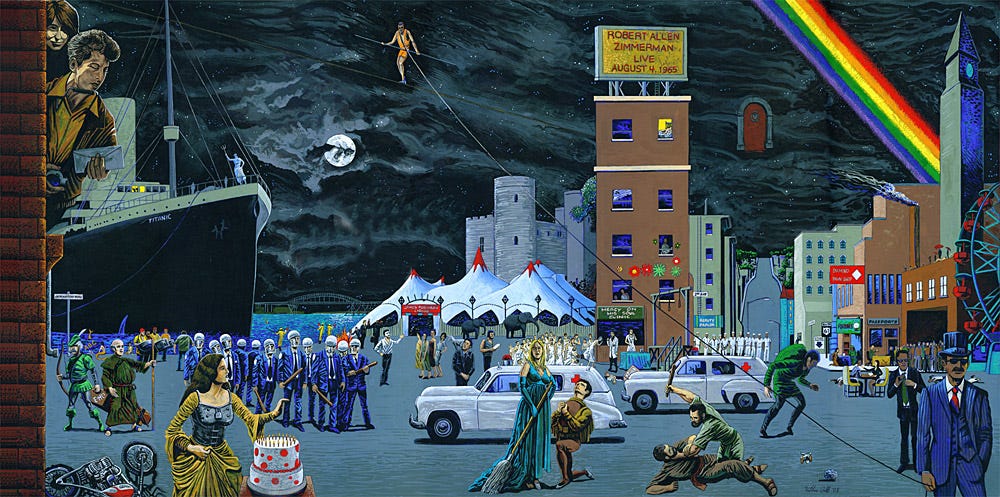

Now It Goes Like This: "Desolation Row"

Tracking the song's live arrangements from 1965 through 2025

Today, another installment in “Now It Goes Like This,” the series where I track a single Bob Dylan song’s evolving live arrangements. I picked one that, after lying dormant for a while, has seen some big changes in the past year: “Desolation Row.”

The song was first played, on Highway 61 Revisited, on two acoustic guitars and upright bass. It was rarely played that way live, though. Instead, it’s largely veered between two extremes: Solo acoustic a bunch, especially early on, and loud, full-band electric. Part of tracking “Desolation Row” live is seeing what verses he will sing on a given night— “Dr. Filth” is pretty rare, “the Titanic sails at dawn” even rarer—but today we’re looking at the song’s musical evolution over the past 60 years.

1965-66: Solo Acoustic Laugh Riot

Dylan debuted “Desolation Row” only a few weeks after he’d recorded it, at his first full “gone electric” show, at Forest Hills. Though, as he would do through 1966, he played it during the opening acoustic set. “Desolation Row” was a ways away yet from going electric.

The 1966 versions are probably fairly familiar to people, via the “Judas” show and elsewhere, but I get a kick out of this very first Forest Hills 1965 performance. The recording quality leaves something to be desired, but in this case hearing the audience prominently is a plus. You’re reminded just how funny some of the lines are, hearing people who had never heard them before (the album wasn’t out yet) loudly laughing like they’re comedy punchlines. Which, in a way, they are. Big laughs at “the other is in his pants,” the entire Cinderella/Romeo verse, “expecting rain,” “playing the electric violin” (that verse, filled with laughs, even earns applause at the end), “some local loser”—and at that point I realized there were too many to keep noting them all now. It sounds like a standup recording from the Comedy Cellar.

It’s not an arrangement difference per se, but compare that Forest Hills '65 recording to this one from Melbourne the following year. It’s so much slower, more tired, more drawled-out. No one’s laughing here.

1974/1984: High-Octane Acoustic One-Offs

After 1966, he didn’t play “Desolation Row” much for the next 20 years. Just two times in fact, once on the 1974 tour and once on the 1984 tour, both during the solo acoustic set. Even given the same instrumentation, though, it sounds fairly different than those '60s versions. In keeping with the rest of the tour, the 1974 version is higher-energy, strummed at a frenetic pace. There’s a reason it’s four minutes shorter than the 1966 one above: he is sprinting through it.

The 1984 performance moves along at a quick clip too, but here he’s doing a lot of upstroke strumming, like it’s a reggae tune. Appropriate given he’d just recorded Infidels with Sly & Robbie. It’s a great version, granting that Bob’s 1984 voice is pretty nasal even by his standards.

1986: Desolation & the Dead

The first time Bob played ‘Desolation Row’ live with a band came in 1986 when he sat in with the Grateful Dead. Which, honestly, sounds like it might be better than it is (then again, if you’ve heard Dylan & The Dead, maybe it doesn’t). Here’s what Rob Mitchum wrote about it a few years back:

Eighteen of those minutes are performed with Dylan on third guitar and vocals, joining in for “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” and “Desolation Row,” two of the many Dylan songs covered by the Dead. The chemistry is palpable, if by chemistry you mean mixing together some chemicals that emit a foul stench. [bolding this because I’d forgotten that line and it made me laugh] Dylan breaks a string almost immediately, and his replacement guitar sounds woefully out of tune and lost in the Dead’s esoteric stew. About 4 minutes into “Baby Blue,” Dylan decides it’s a duet now, yelling over Jerry for the rest of the song. “Desolation Row” fares about as well, with the Two Bobs stomping all over the song’s poetry in a hammy frontman competition. By the end, both of them are struggling to sing from laughing, and you might be chortling right along.

“I found myself in the weird position of teaching Dylan his own songs. It’s just really strange!,” Garcia said of these sit-ins in Blair Jackson’s biography. “It was funny. He was great. He was so good about all this stuff. Weir wanted to do ‘Desolation Row’ with him, y’know, and it’s got a million words. So Weir says, ‘Are you sure you’ll remember all the words?’ And Dylan says, ‘I’ll remember the important ones.’”

Spoiler alert: He did not remember the important ones.

When you listen, you might wish he’d remembered even fewer words. Him yelping them with (“with” is a generous term, it feels more like he’s yelping them at) Bob Weir is a tough listen. Or maybe, depending on your disposition, a hilarious one. I laughed out loud a few times listening to this. Wild that he apparently came out of this thinking, “I want to hire these guys so we can do this every night!”

1987: The Heartbreakers Wing It

On the actual Dylan & The Dead tour in 1987, they did not play “Desolation Row.” Perhaps they knew just how much a trainwreck their one-and-only collaboration on it was. It’s not even on the extensive pre-tour rehearsal tapes.

Dylan did, however, bust it out later in the year, when he was again backed by Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers. Benmont Tench recalled to me:

It wasn't very hard to teach us a song — and sometimes he didn't teach us a song. He just started playing it. It didn't matter if there were 20 or 60 or 70 thousand people watching. Not often, but every now and then, he just would start playing. That's the best kind of playing, in a way, if you know the song inherently but you've never played it. I'd never covered “Desolation Row” in a band. I'd never played it in my life. I’d just listened to it a million times. At a festival, he just started playing the chords. Within four bars, I was like, “Good Lord, we're playing ‘Desolation Row.’” We were off to the races, and it was beautiful.

You can actually hear that on the tape. Dylan starts strumming the chords alone on acoustic guitar. After a few bars, the band gradually catches on, sort of stumbling in one by one. By the time Bob finally starts singing two minutes in, though, they’re on it. It turns into a beautiful performance, one of the best we’ll hear.

Compare that to the next performance two nights later. This time, they’ve prepared. Instead of Dylan strumming on acoustic, the song starts with Tench doing a beautiful piano part behind Dylan on harmonica. No awkward stumbling in behind Bob this time. They’re ready from the jump, and it shows. Another gem.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Flagging Down the Double E's to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.