Mitch Blank, Bob Dylan Preservationist, Talks About His Decades of Collecting

"Sometimes I've known people for 30 years before the moment would happen"

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

“Collector” is the easy word to describe Mitch Blank, but it’s not the only one. Historian. Preservationist. Archivist. Those all apply too. The latter in a formal way; he’s now a consultant with the Bob Dylan Archives in Tulsa, alongside fellow supercollector Bill Pagel. If you visit the Dylan Center and look at the fine print under certain items on display, you’ll see “Courtesy of Mitch Blank.”

I met up with Blank at his Manhattan apartment earlier this year, not long after a Dylan Archives moving crew had taken 10,000 (!) items from his collection off to Tulsa. Even 10,000 items lighter, his place felt packed with music history. Dylan’s, of course, but of his many other passions too.

We talked about how he got into Dylan in the ‘60s and what he calls “the disease of collecting.” He’s reluctant to play the do-you-have-X game on the record—when he worries about fans showing up at his doorstep, he means it literally—so our conversation is more about his methods for acquiring so many Holy Grail recordings and items generally, as well as his more esoteric interests (like thousands of bookmarks with Dylan pictured on them).

What was the first thing you collected?

Because I am of the 1950s, one of the altered state of consciousness that I first encountered was plastic rubber dinosaurs by the Marx Rubber Company.

Like children's toys?

Like little rubber soldiers, but they're dinosaurs. I have boxes of them. They're probably lying around the apartment even now.

But [as a kid,] what do you know from collecting? The word “collect” doesn't exist. The word is, “whaddya got?” Kids don't have a lot. My family didn't go crazy with commercial toys. You made your toys. These were the currency of youth: bottle caps, baseball cards, other cards, comic books. To call yourself a collector, even in 1950, you would have to have been somewhat deeper pocketed than the average bear. But people had stuff.

You'd get books of matches at the store. They'd have different birds on them. I'd collect those. I gotta put them together, because the universe is absolutely out of order. I think as you get older, you start understanding the idea of what a “collection” is. Collectors work off of a list. They have some basis of their quest. They have to draw parameters on what they could feed the disease of collecting with.

At what point does Dylan enter the picture?

I guess for most people on the East Coast of America, Dylan enters their world in the very early parts of the '60s. By 1962, we're already singing Peter, Paul, and Mary songs, which are Bob Dylan songs.

Are you aware of album number one at the time, the self-titled one?

Not so much, to tell you the truth. I had Freewheelin’ because in that era, in order to suddenly have an instant “collection,” I had to be a member of the potential debtor prison of the Columbia Record Club. You could get 10 records for a penny. Maybe sometimes a secret record added on.

It becomes the clay that forms your personality. What are you listening to? What are your friends listening to? What did you get because your friends were listening to it? What are you only listening to in private when no one's home?

For me, it was Top 40 AM radio. The more you listen to radio and the more you listen to other sources, you start to hear more about this person Bob Dylan. You went, "Oh, you wrote that song…"

I saw Bob Dylan for the first time because I went to a Joan Baez concert with a neighbor. It was at Forest Hills, “a summer of folk” or something. They probably had Peter, Paul, and Mary, maybe others.

Was Dylan on the bill, or was this Baez bringing him out for a couple of songs?

That's what it was. There's a recording of this. I'm not sure exactly the date, but it might have been summer of '64.

You knew who he was at the time? When she says “Bob Dylan,” you at least vaguely were like, oh, I think he wrote some of these songs?

I was a camp counselor with younger kids. Part of that world was someone playing a guitar around a fire. You got a vocabulary of songs that were being brought to you. I think that's how I got to hear people playing Bob Dylan music. I said, “Wow, that's really great. ‘He not busy being born is busy dying’? Oh my God.”

If you want a whimsical version of it, a wind blows through my neighborhood, Woodside, Queens. Brings with it a mutating gene. The people who went to my high school, in different years, were Suze Rotolo and Sally Grossman. Maybe it was something we caught.

You didn't know either of them at that time?

I did not. Only later. Many years later were we sitting in Seattle around the table drinking free vodka listening to a Bob Dylan cover band, and this came up.

I can't imagine Suze going to see a Bob Dylan cover band.

It was the opening of the Bob Dylan Experience Music Project. It traveled around the country. We got flown out there. I went out there with Suze and her husband. Bruce Langhorne was there, Izzy Young, Sally, a lot of characters.

How does it get to the next step where you start actually tracking down Dylan stuff, looking for more?

First you have to figure out, "Wow, such a thing exists?” More? How do you find more?

Bootleg records are not in your face at that point yet for me. Bootlegs were pretty much part of a world of jazz and opera. Who knows what reason. People had maybe permission to carry a giant machine into a room and tape things. This was not the case necessarily [in pop] unless you were in media and you had a radio show.

A lot of the recordings that we archive now are because of these situations. Musicians who have no money would gravitate to anyone who owned a Wollensak [reel-to-reel tape recorder]. It's only because that person had a recording and then, somewhere down the line, someone found the need to look for it.

Especially the first few years of the Dylan bootleg tapes we have, it's often either a house or an apartment where someone has a machine or it's a radio show like Cynthia Gooding’s.

Exactly. So how does anyone know about any [unofficial] music? Well, because those bootlegs are played on late night radio, underground radio. You heard things there in the middle of the night. They didn't necessarily get hype because they were not for commercial release.

You also started meeting other people who were a little older and more embedded in what we now would call musical archeology. So I got on that train somewhere.

There's a story in the Tell Tale Signs bootleg series where Larry [“Ratso”] Sloman writes about being on line at the Fillmore East and buying the Great White Wonder bootleg record that was being sold to people who were waiting on line. That music was coming out post-motorcycle accident where people were thinking all kinds of weird stories. What's going on upstate? These guys, The Band, are they religious hobos? They wear these like Hasidic hats, what?

This is the first time that what we now call the Basement Tapes are appearing, in horrendous quality. This is the first time people are hearing things that are being snatched from oblivion. A mythology develops around material that's part of an iceberg that exists mostly under the water.

Does that add to the appeal to some degree?

Of course it does. Especially when a bootleg record would come out, and it would be the Manchester (formerly “Royal Albert Hall”) concert. That's a life-changing event for me.

How long after it happened would this recording have come into your possession?

I saw that Manchester show as a vinyl bootleg. You either saw it in a store window, in neighborhoods that maybe were not frightened of selling unauthorized material, or you knew the signals. Like a freemason, go into a record store, do the signals, and suddenly things would appear from underneath the counter.

What were the signals?

I could tell you, but then I'd have to kill you. That’s how I got the 18-and-a-half-minute Nixon tape. You have to use the right signals.

At this point, you're buying bootlegs in record stores. How does that transition into you acquiring or hearing about material that is not being released on "commercial” bootlegs.

With anything else, you run out of material that is low-hanging fruit. Now you have to work things backwards, like any person doing research. Try to discover, what does exist? Where it might be? Is it already sitting in the holdings of the people responsible for Bob Dylan's archives? Because you don't want to be doing research, calling people, traveling, if someone else has already uncovered what it is that you're looking for.

How do you get your foot in the door? When you don't have a reputation, no one knows who you are. How do you hear about anything?

I started reaching out [to people]. I couldn't go online and suddenly collect all 40 shows from the 1974 tour with The Band by contacting one guy, and he would send it to me overnight on a zip drive. I’d have to know 40 people in 40 cities.

Would you just send out letters?

I would. In the early days of newsletters, prior to anything that was more formed that became a fanzine, there was a network of people who found each other through writing letters. [In around 1978], I saw an ad from a gentleman who had written a note saying that he was looking for people who also had some knowledge of doing Bob Dylan-related research. He was thinking about putting a magazine together. So I wrote a letter to the gentleman, named John Bauldie.

One day my doorbell rang. In New York City, when your doorbell rings, generally you boil oil or go look for something that can be used as a weapon. I believe I had some friends over at the time, and I buzzed the person in. A gentleman dressed much better than most of my friends was coming up the stairs. It was John. He said, rather than write, he thought he would just come.

By sorting out who was researching what so we're not stepping on our own feet and digging the same hole and bothering the same people, this was at least a way to have a clearing house for people to do their thing and actually get the help of a wider range of people who had the information that they might've been looking for.

Do you remember any of your first discoveries or finds that excited you, that weren't on bootleg records already?

In that era, there arose an evening called the Bob Dylan Imitators Contest. For 11 years, from about 1981 to whenever it collapsed, there was always a packed house because we had celebrity judges. The judges were people I would gather from the expanded Bob world. I got closer to people like Cynthia Gooding and others. I got to be more familiar with what kind of recordings had been being created during the club scenes. [More on Gooding’s tapes here]

During the period of time that Cynthia was on the air with her radio show Folksinger's Choice, which ran from about 1959 through 1962 and of which most people are familiar with Bob's appearance, there are a lot of recordings that took place in people's attic's, basements and living rooms. Once I realized that people had tape recorders, it became necessary to figure out what really exists. A lot of that material falls outside of Columbia and their studios. A lot of it is taking place in private environments. It's not necessarily going to be instantly scooped up.

We rescued the Cynthia Gooding collection, which is dozens and dozens of recordings of the folk scene. There were hootenannies, there were clubs, there were recordings from a variety of clubs. Some, yes, have Bob Dylan.

Most of the recordings that I've worked on putting into the now-known body of work now live at the Bob Dylan Archives in Tulsa. A lot of these recordings sat in environments that were not healthy, in garages and all of the most horrendous situations imaginable, for decades upon decades.

I was directed to certain squirrel holes by people that I allowed to have trust in me for a very long time before they decided to deposit knowledge that would be useful for everyone else. The idea is to do the right thing and not create an industry for [some bootlegger] in Germany, and also to help people receive the karmic kickback that they've perhaps been waiting for.

You mean the people who have been sitting on their tapes for 30 years?

Yes. I never pressure people, but I let them know that if they want to take a different approach to their collection or their legacy, that they can talk to me. I'm not a player in the game. I'm not in competition. I don't buy manuscripts and deep-pocketed things. I'm still buying rubber dinosaurs.

At what point do you become connected to the Dylan office?

First of all, I don't know if I have any official connection to the Dylan office whatsoever.

You have an official connection to the Archives though.

We all share the same DNA. Nowadays I am considered to be a consultant for the American Song Archives, which is the umbrella for the Bob Dylan Center and the Woody Guthrie Center. I've recently donated a lifelong collection of ephemera and material that reflects a more whimsical side of how the world of Bob Dylan has worked its way into popular culture. There are books of every cartoon with Bob Dylan, or any comic book that had Bob Dylan in it. There are books of bookmarks and God knows what.

How do you find every bookmark with Bob Dylan on it?

You don't find every one.

How do you find any of them?

Years ago I had a small collection of snow globes. I had like five or six of them, and then people would bring them to me. The next time I looked around my apartment, I had 300. You say to people, “No more snow globes.”

So is that how you end up with Bob Dylan bookmarks and comic books? People just have a sense of what you're interested in.

Yes. Like anybody who is doing any kind of musical archaeology, the main way you're going to attract any connection with the people around you, you have to let people know.

I had thousands of instances of postcards or programs or whatever media of any artistic exhibition that deals with any Bob Dylan-related extrapolation. Once foreign collectors know that you smile when you open up an envelope and things fall out of it, people will bring you things.

Keep in mind, the most important part of all of this is the music, and just the music. The audio, the video. The rest of this stuff is what it is.

For instance, now in Tulsa they have what we now call the Bailey Collection. The Baileys were friends of Bob and Suze when they were a couple, who they knew from probably Gerde’s. They also had a very good tape machine. Therefore Bob used that machine to teach himself how to use a mic and sing his earliest known written material. There's a lot of extraneous material on there as well.

Other collections that fall into that category would be the only recording of Bob Dylan having left Minnesota, before he gets to New York, and that is now called the Madison Tape. The Madison Tape is Bob, mostly in his Woody Guthrie Jukebox mode. He's singing with, amongst others, Danny Kalb. That is now in Tulsa.

There's still a lot of material that's been identified, where there is an idea where it might be. I use the expression “buried.” The first thing is people need to trust what you're doing. You give more than you take. If somebody has a recording and you show them what recordings exist prior to their recording and just after, and they see how it's a link in a chain, people are much more interested in participating in that chronology. It's not some money-making scheme, but it's part of the historical record.

In terms of Bailey or Madison or anything of that ilk, is there a story you can share about how you found it?

It's not as though these things are necessarily hidden, and you have to find a treasure map. You know people who will open up a door, and then you'll explain to the people on the other side of that door that you're not a bull in a China shop. You say, "Oh, your uncle made that recording? Fantastic. Let me play for you a recording that my uncle made." You grow a symbiotic understanding that we're all talking about the same thing.

It's easier to say yes than it is to say no. People want to help, but they want to know they have permission to do it. A lot of people gave some spiritual vow at some point in a different era.

Then other people just smell money.

It's hard to compete for those people, I would imagine.

If I'm close enough to them and they smell me, they're not going to smell money.

I live in Greenwich Village. Here is where the story is. The people I meet who gained from material I have of artists other than Bob Dylan are constantly exposing new possibilities of squirrel holes.

Would it be harder if you lived in Boise, Idaho?

I don't know how you would do it in Boise, Idaho. Probably within a few months, you would have exhausted every good recording in Boise. But maybe not. People are people. People sit on things. A lot of recordings that we've been trying to add to the known body of work are not existing in the environment where they were recorded. They've moved.

We're living in an age where people who are getting on the Bob Dylan merry-go-round are able to download 27 galaxies without traveling from their couch. All the work, all the little pieces that got put together one by one by one, are now potentially available to somebody on a whim.

How do you feel about that?

This will certainly keep interest alive. And I'm meeting people all the time who have absolutely unique, sometimes visionary, ways of looking at things. There's more different kinds of people involved in this world than I've ever been exposed to before, thanks to symposiums that are taking place in Tulsa. I would have to encourage everyone within your readership to please make a pilgrimage to Tulsa to see what a miraculous situation they've created. Go to Oz.

How did you get connected with the Center and the Archive initially, back in the early days when they were conceiving it?

It's an incestuous world. Everybody knows everybody. If you do things in secret, then nobody knows what you're doing. The things I've been doing, it's pretty much an open resource for anybody with a healthy idea.

Of the stuff the Center has got on public display, do you remember any examples of what would say "Courtesy of Mitch Blank" in little letters at the bottom?

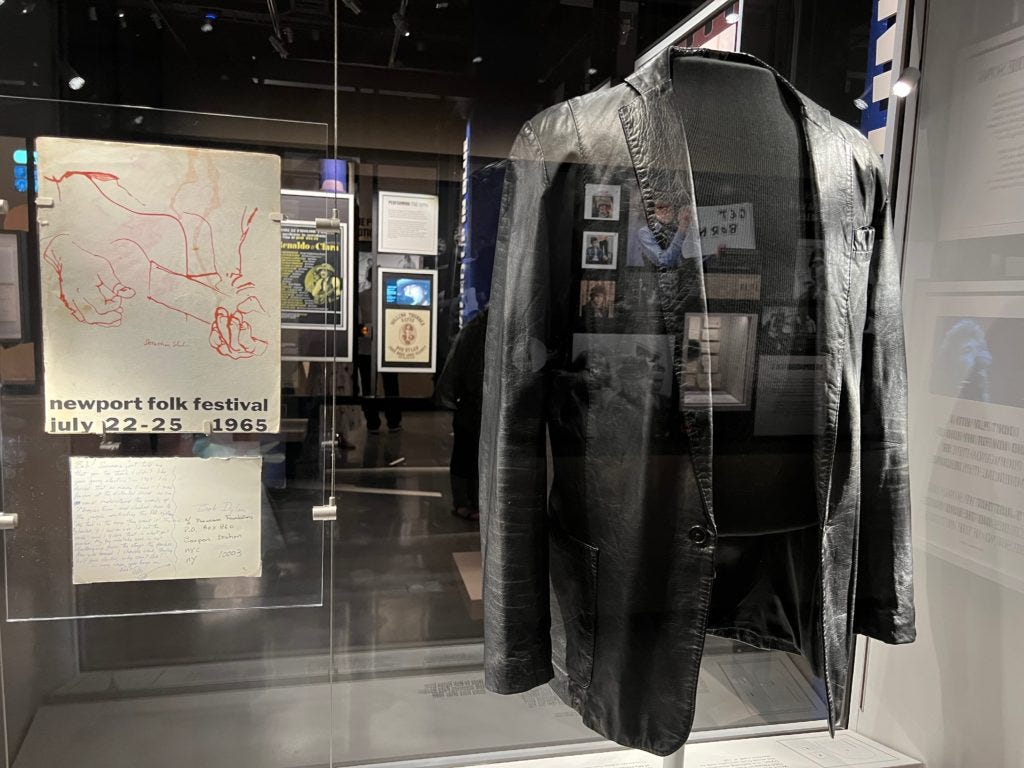

One of the things I'm most proud of is that my program from the 1965 Newport Folk Festival is now living in a glass cabinet right next to Bob Dylan's black leather jacket from Forest Hills. It's just a beautiful thing to stand next to. They live together. They're roommates.

Were you at Newport, or was that something that you collected later?

No, I was not. Paper was something I gathered from all original sources, all the ephemera of programs, flyers. We just sent 10,000 items to Tulsa.

A lot of the stuff doesn't necessarily have my name on it. I remember when I was over at the Dylan office and they were putting together that gospel Bootleg Series, they said it'd be good to have some kind of video thing. This was before they decided on that movie [a quasi-documentary combining concert footage and Michael Shannon’s preacher shtick]. I was going out to Hibbing for whatever. I was excavating at Bill Pagel’s. He has things buried away that are earth-shattering. That’s where we got that Bloomfield [unseen video of Michael Bloomfield sitting in with Dylan in 1980].

When I found it, it was in much shittier quality. It was not synced up. I see this stuff and I go, “It's fucking Bloomfield!" This is like two weeks before he dies.

I think it was the last performance known.

It was, the last known footage. I confiscated it from Bill, that and some other tapes. We got back to New York, got back to the Dylan office. We called everybody in the office. I threw it on, in the format that I had it. It looked okay, but it was not good. They sent me to the video studio. They corrected the color and they fixed the speed and they balanced the thing. We sat there for a whole afternoon and watched them do this. It was really amazing the work that they did. We just watched it and said, "Wow, look at that!"

We talked about collecting tapes. Were you ever much of a taper yourself?

No. I hate stuff like that. It makes me nervous.

I was once wired for a situation where some artists, not Bob Dylan, was going to be doing something at a tribute concert. I was in one of those box seats, sitting between Judy Collins and Harry Chapin's mother. Folks that I didn't know that well had wired microphones into my hair and a thing going down the back of my shirt. I just sweated, like dripping. I couldn't wait to get out of there.

When I was in college, some taper was trying to convince me to tape a show near my school. He was giving me advice like, "You gotta buy this sort of hat so you can hide the mics…” I was like, "I'm going to have a panic attack just listening to this." Didn’t have the fortitude.

I've seen people do things like convince a person in a wheelchair to let them shanghai the wheelchair to bring equipment and stuff.

I've heard of wearing a fake cast.

Oh yeah, everything. Nowadays, people have something that looks like a hard drive. It doesn't even look like a recorder of any sort. The technology is so advanced that the people who would be checking for such a thing don't even know what they're looking for.

I've never been a taper, but I have been the interference guy for the taper. Sitting next to the person to keep people from talking. Never talks, never moves his head. You’d never know he's alive.

[One time] he gives me a signal. He means he can hear the guy next to me talking to his girlfriend. I say to the guy, "Listen, if you just don't talk, I'll give you a copy of the tape at the end of the show." He goes, "Okay."

Turns out this guy was in a position to build a wing at the Dylan Museum.

Because of that interaction and you sending him the tape?

Yes, because of that interaction. Weird, isn't it?

You’ve used the phrase "the disease of collecting." Is there something, an itch maybe, that some people have and some don't? Most people read a comic book that mentions Bob Dylan, and when they finish it, they pitch it.

We come in a lot of different ways. There are people who if they see Bob Dylan's name in a Superman comic, they would buy 11,000 more of them. I know people who would try to find any other instances like that, so that they can feel that they can control the universe of where that is. There are people who, maybe they're healthy, they throw it away.

I was blocked from stuff that gives me joy, material that's been so tucked away in my apartment.

You mean because you had so many piles of stuff literally blocking other stuff here?

You saw what it looked like before. There was all kinds of material recently being organized and boxed, labeled, numbered, to be brought to Tulsa to become part of their greater archive.

Since that happened, have you rediscovered things that you've had but haven't seen for years?

Absolutely, absolutely. Almost everything you're looking at.

When you ask about the disease of the collector, I don't own anything that doesn't have a story. There’s just a lot of stories going on around here. The more you do, the older you get, the more shit is going to attach itself to your planet. I'm trying to find proper homes for a lot of the material that needs better care.

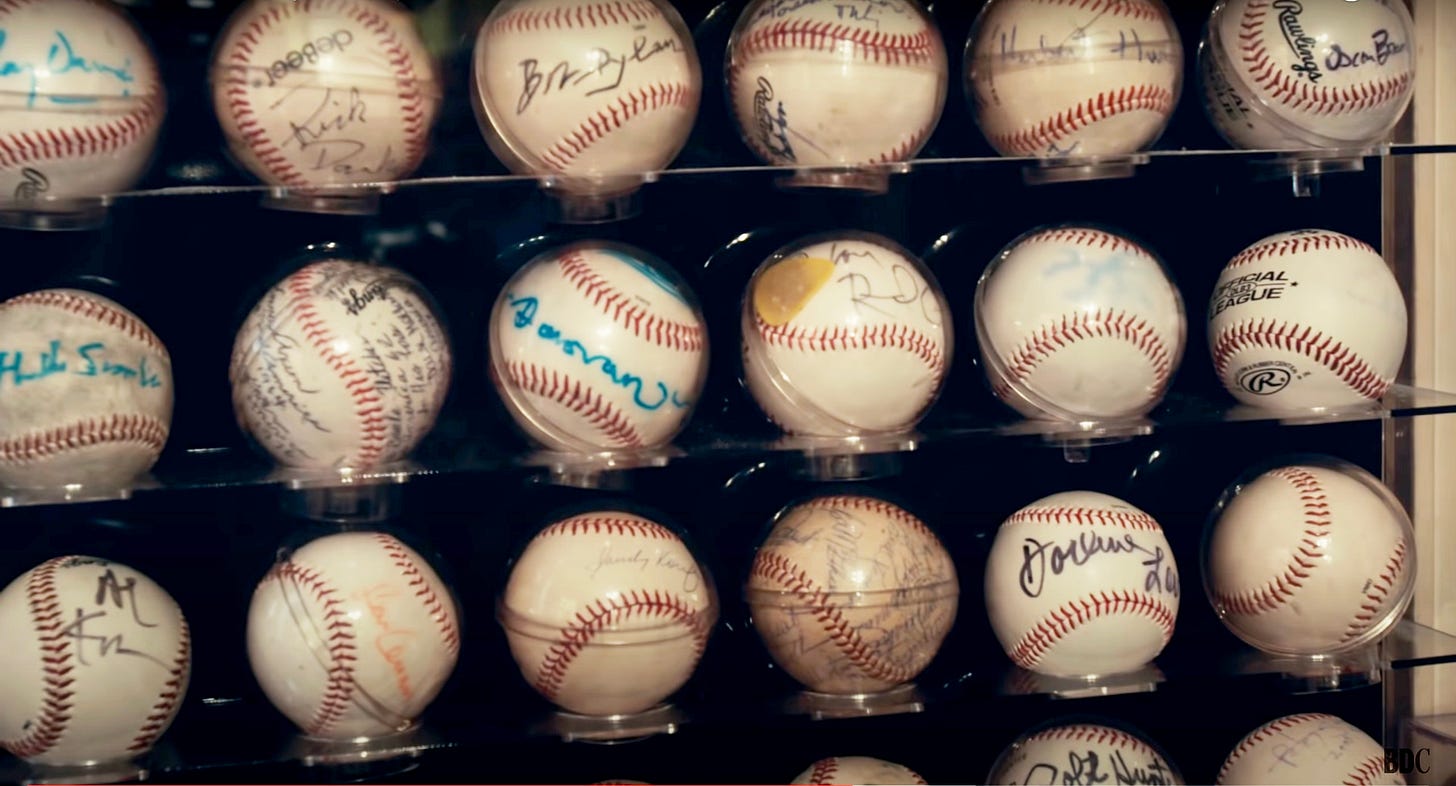

You’ve still got the wall of signed baseballs. What's the story behind those?

For years, I would work with different artists, or Beats, or writers of all sorts. Rather than getting people to sign album covers, it was just so much easier to have people sign baseballs. Especially if you give somebody a Sharpie and a clean baseball, most people will take advantage of it. There are people who won't sign things who will sign a baseball.

You have a Dylan one, right?

I do. It was a gift. I have a Donovan one. He drew a third eye on it. I allow people to decorate their balls.

What are some of the most unusual things in your collection?

One night several years ago, I’m sitting here with a couple of my interns. The Chelsea Hotel was being renovated at the time. They were selling the doors from the apartments for gigantic money, like $100,000 or something, because they could prove that certain people of notoriety had lived in different apartments.

Anyway, so my interns were going, "Oh, Mitch, did you see they're selling pieces?" I said, “They're renovating 161 West 4th Street right over down here.” That's Bob's first apartment with Suze. They're got the whole front coming down. I said, "Why don't you guys go over there and take the address off the door?"

I gave ‘em a screwdriver. I felt like Manson with his dune buggy girls. A while later they came back. They brought me back the two 1’s. The 6 had been previously taken by somebody else.

That's amazing. Who needs a $100,000 door?

My old apartment, in the early '80, I used to get a lot of visitors. People would come by and they'd see Rob Stoner sitting here or Howie Wyeth, and then they'd extrapolate these imaginary truckloads of things that people are giving me. All these rumors. I said, "No, it's not happening like that."

Nothing I do, I would not even think to do it if it was not for Ian Woodward and not for John Bauldie and not for Sandy Gant and some of the early people who were going to people's apartments and houses and asking them to share recordings before anybody else showed up to drive them crazy.

Do you have any advice for other would-be Dylan collectors or preservationists?

People ask, how do you get your foot in the door? Well, you get your foot in the door by finding something that opens up the door. It doesn't have to be earth-shattering. You don't have to find the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Your readers should know, if there are people who are on the trail of trying to uncover any kind of a historical document of any format, to move slow. To convince people to put what they've curated into a responsible stabilization, they have to take their time. Sometimes I've known people for 30 years before the moment would happen that the material that they protect is now able to move to historical preservation.

Thanks Mitch! If you want to experience some of his collection for yourself, make your way to the Dylan Center in Tulsa and keep your eye on the fine print. Here’s a short video the Dylan Center did with Mitch a few years back:

Great interview - what a sweet guy.

Mitch lived downstairs from me for many years. Great guy!