Mike Evans, Bob Dylan's "Big Police," Talks Security and Food Fights on Rolling Thunder

"I go upstairs, and it is like Animal House…"

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

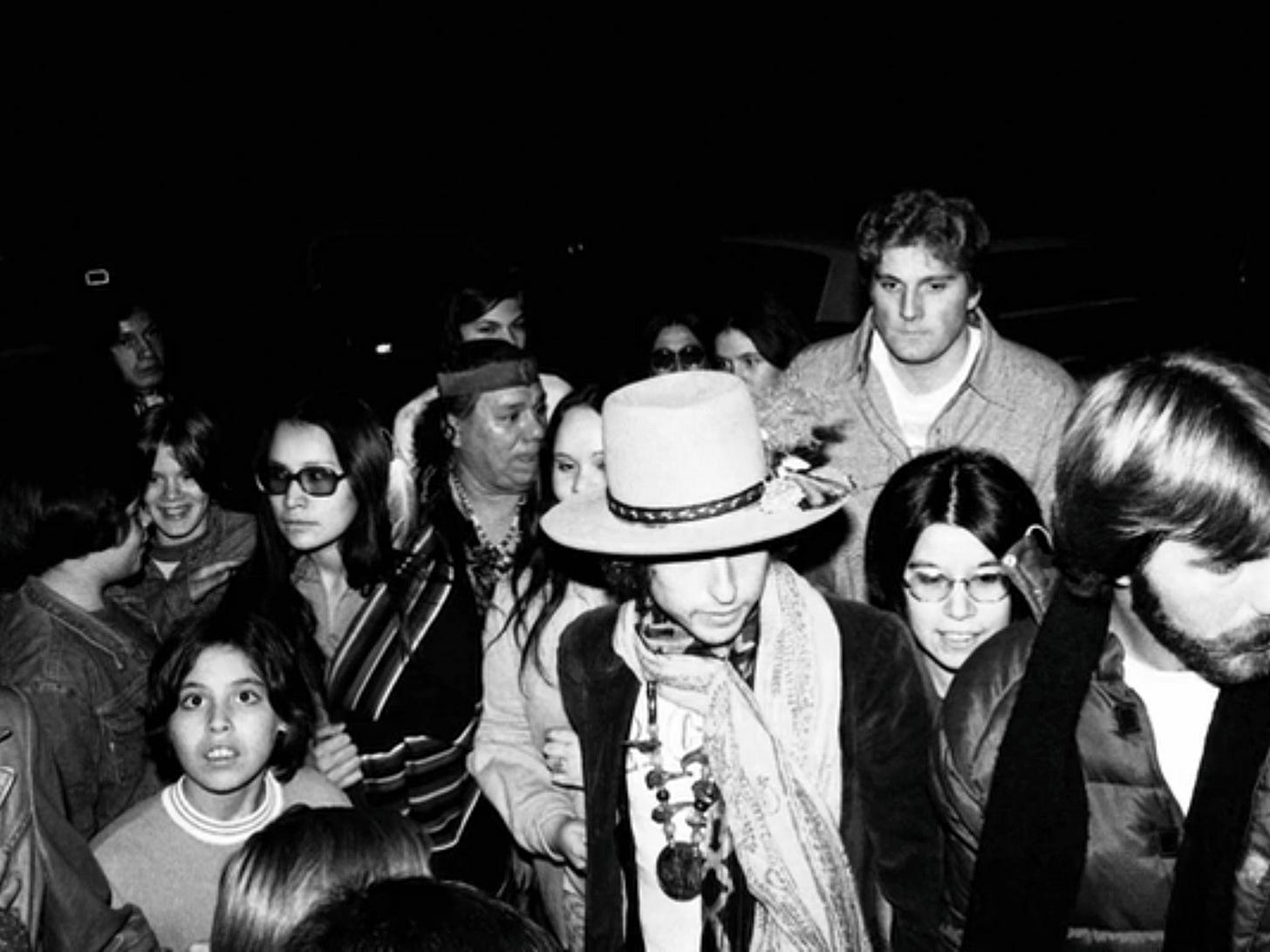

In Renaldo and Clara, Bob Dylan’s movie documenting the 1975 Rolling Thunder tour, Mike Evans’ team gets credited as “Big Police.” Promoter Barry Imhoff gave them the “Masterpiece”-nodding nickname due to their role overseeing security for Dylan and the musicians. You can see Evans himself guiding-slash-shielding Dylan in the above still from Martin Scorsese’s Rolling Thunder film.

Protecting Dylan from biting fans (we’ll get there) was only part of his job though. He also oversaw advance show promotion, making sure the word got out locally often with just a few days notice, and various other tour logistics, making sure everyone was in the right place at the right time. With such a large and ragtag crew, that was no small feat.

He’s stayed in the music business. These days he’s the President of Live Nation Arenas, where he oversees shows in much bigger venues than some of the tiny rooms Rolling Thunder popped up in. We recently talked about all the work involved in keeping Rolling Thunder rolling.

I live in Burlington, Vermont, and I was alarmed to hear that a Dylan fan bit you on the Rolling Thunder stop here.

Every summer, poolside with cocktails, inevitably after the second or third, somebody will say, "How come that one place on your wrist doesn't tan?" I say, "Well, I was bitten by a savage animal."

Vermont, man, we're supposed to be like hippies…

I know there's one meat eater up there.

It was really an inadvertent thing. Bob was walking in front of me, and he had these big feathers in his hat. The guy reaches out for the feather. I slowly just grabbed his hand and pushed it back. It was just a real gentle, "No, no, no." Like you'd say to a two-year-old: "Don't touch that." Then all of a sudden this guy has clamped onto my wrist. He actually got a chunk of skin. Besides being painful, it's just the way it healed. It just kept getting infected. Just cleaning it out and having it rewrapped and everything else was nuts.

I wasn't even alive then but I still feel obligated to apologize on behalf of Burlington.

I've never held it against the state of Vermont.

Let's rewind to happier times, before you got bit. Barry Imhoff hires you for the tour. What are you hired to do exactly?

Like a lot of things on the Rolling Thunder tour, everything was moving at such an intense speed and a lot of it hadn't been done before. What Barry wanted me to do was threefold.

One, the original intent of the Revue was that we would just show up in town and do a show. That's where the name Revue came from. It wasn't like, go on sale and six months later you have a concert. We would just show up.

I needed box office people. What those people would do is they roll into town and start handing out handbills. The way they used to do with the circus, saying "The circus is coming to town." In this case it was the Rolling Thunder Revue. The plan was to sell usually the day before, so that you were dealing with local people. Get the tickets in the hands of the fans. Scalpers weren't getting hold of them,

The next tranche of three were to provide one very close body person to Bob. You needed someone that we could coordinate with. “Where is Bob?” “What's needed?” Things like that.

Then the other group, I would have a guy that basically was the sheep-herder to would handle the band, whether you call them Guam or the musicians or whatever. If we said, "This bus is leaving at four o'clock," making sure they're there at four o'clock. Which was a yeoman's task with this group. You don't have cell phones. We had walkie-talkies, but people would get spread out.

Then I would be the point person. I would take my marching orders, if you will, from Barry and Lou Kemp. I quickly learned that Bobby Neuwirth was going to be my man. Bobby had one foot on the business side and one foot on the artists side. If we're in a hotel and there's a ten o'clock curfew, and these guys decide they want to rehearse at 2:00 AM, Bobby is the one that I could say, "Make sure they stay in this room. Don't be walking the halls with alcohol, because if I can't keep the hotel manager in line, we're going to have police here." Neuwirth and I became close. Real close. I wish we could have maintained the relationship. I have great admiration for Bobby Neuwirth.

Then it would be doing a lot of advance work too. It’s so simple today, because you're playing venues that have been there, and it's basically computerized. But we were playing unconventional rooms. On the day of the show, I was more focused on what the next two or three shows were than I was on the show in front of me.

Imhoff called my group the Big Police, after the lyrics in Bob's song “When I Paint My Masterpiece.” That's the way we were listed in Renaldo and Clara.

Were you doing personal security too, if you're the guy who's trying to stop people from stealing his feathers?

Well, it's like the show's over, Bob's going to the Winnebago. Andy [Bielanski] and Gary [Shafner] were most likely walking in front of him. I'm just walking behind him to make sure. I'm like a mother hen in a lot of ways.

I think part of the problem [in Burlington] was us being at, again, an unconventional venue. Most venues, Bob would have entered through his vehicle underground and things like that. But he had to walk through a parking lot.

I imagine that also came into play with all the filming for the movie. It's not like Dylan is hiding away for 22 hours a day, other than the show. He's out on some boat in Cape Cod or visiting a Native American reservation. He's going all over the place during the days.

The plan was, in the mornings, while everyone is still sleeping, Barry, Lou, the film people, we would be in the lounge. We would be talking about, "What's going to go on today?" Neuwirth the day before might have said, "Hey, let's take everybody to Jack Kerouac's grave."

I would then grab my guy with Dylan and say, "All right, you need to be back by X. I don't care what time you get there, how much time you spend there, but you need to be on your way by X.” We'd make the film crew aware of that too, but you know what film crews are like. You tell them from ten to eleven to do this, and at ten o'clock the guys are all on break. Or they would get there and say, "It’s cloudy. We want to wait an hour for the sun to be out."

You can make all the schedules you want, but there was so many impromptu things. You could be driving down the road, and Neuwirth would say, "Oh, look at that diner. That'd be cool to shoot." They're going to pull over and do it. I can't control the day when they're filming, but I can control what time they need to be back.

Do you remember the first time you met Dylan himself?

I was in New York. We picked up two Cadillac DeVilles. It was the last year the Cadillac DeVille was going to have a convertible.

These are for what? To drive around on the tour?

Yes. I remember Andy and I drove one from Quebec to Toronto. I think Lou drove one of them. Memory is light. I don't remember driving one at the beginning, because I had rented a Granada at Hertz that had 10 miles on it. When I turned it in, it was 22,000 miles.

When we came back [from picking up the Cadillacs], Bob was standing out in front of the Chelsea Hotel. We all stood around there. Neuwirth goes, "Hey, this is Mike." He knew who I was.

I would talk to him every day. He might talk to me every fourth day. Usually that was, "Got it. All right."

Can you just describe what your job was on a typical day,? You get up before everyone else and you're meeting with Louie and stuff. What happens next?

We have a time where everybody's supposed to be at the hall, usually that would be about 3:00. We always made sure the stage and everything was set up by three o'clock, so we could do rehearsals and stuff. Having so many musicians, having so many people come in and out, changing the set list constantly. I would be cognizant if Bob was off doing filming. We had CB radios that we would communicate with.

I would then probably work out of my hotel room, then go over to the hall, mainly because there'll be lunch there. Then at about one o'clock, start working on any issues where we're going to be playing the next day. Three o'clock, the artists start rolling in. Then you get a report that Artist A decided to go to this amusement park 50 miles away. There's always something.

Then there would be one or two things. If we're staying in that town that night, we were big on setting up lounges. Rooms where the artists could be. We'd have something set up where these guys and gals could sit around and jam and everything else. We had an unwritten rule: You could bring one guest from the outside. If that guest got out of line, we'd deal with it.

When people came down, we would have a luggage call. We actually had Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky, his partner, handling it. They took the luggage situation seriously. They would check and make sure everybody had dropped off their luggage. Inevitably somebody would have left it in their room, so we'd go get a master key and deal with that.

That's funny. Ronee Blakley told me that Allen and Peter were moving luggage. I didn't realize they were so organized about it.

Oh yes. They took it seriously. They were a big help. Particularly Peter. Allen was Allen, but Peter was the nuts and bolts and the sweat.

You get the luggage, you're heading to the venue.

We get to the gig, they're doing their sound checks. If it was a normal venue, I would know the people. If not, I'm getting to know the people. Re-coordinating when the doors open, who gets to go where, what the passes mean. We had a great pass system all coordinated around different colored buttons. I had to make sure, all right, T Bone Burnett is wearing the button from three shows ago. Tell him it’s orange tonight.

The problem was, of course, these guys were always roaming around. They'd go out in the house and want to watch other sets. The touring people themselves all had a laminate. Each day we probably had to make three or four laminates because oh, Joni Mitchell is here tonight and her manager and her agents need credentials. That was a major deal to do that kind of thing, to pack up and move lamination materials and everything on the road.

Like your own little traveling Kinkos.

Yeah. All goes in the road case.

Then the show would start. We didn't really have issues with people rushing; this isn't a show where people are going to rush the stage. So I'm now figuring out, how do we get out of here? If we're going to the hotel, do we need food, or are we getting on the bus and traveling?

Where are you during the show itself? Are you backstage working? Are you side-stage watching?

I'm backstage for sure. Walk out in the house every so often. I will be out front probably, just out of habit, for the main artist, Bob. “Hey, I really like when Bob Neuwirth and Dylan do ‘When I Paint my Masterpiece,’ I want to go watch that." The band is going to do 30 minutes of instrumental stuff? That's a good time to go call my wife.

I wanted to ask just about a couple of specific shows. The one where they played the prison, the Hurricane Carter thing, that must have been different than your typical gig. Speaking of nontraditional venues.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Flagging Down the Double E's to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.