Larry Campbell Goes Deep on His Eight Years with Bob Dylan

1997-03-31, Memorial Stadium, St. Johns, Newfoundland, Canada

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan shows of yesteryear. Free subscribers get one or two posts a month, paid subscribers get several times that (and can even assign me a show to tackle). If you found this article online or someone forwarded you the email, subscribe here:

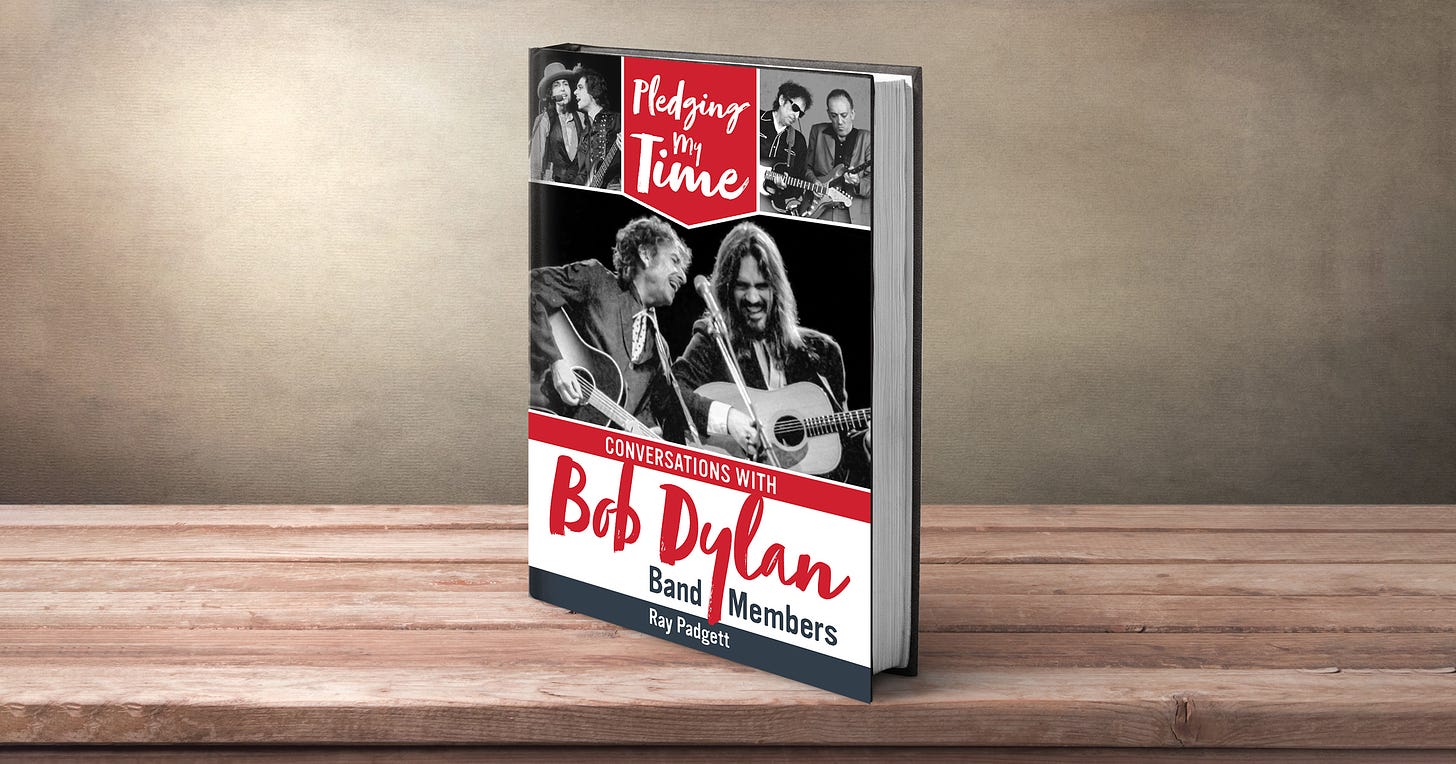

Update June 2023: This interview is included along with 40+ others in my new book ‘Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members.’ Buy it now in hardcover, paperback, or ebook here!

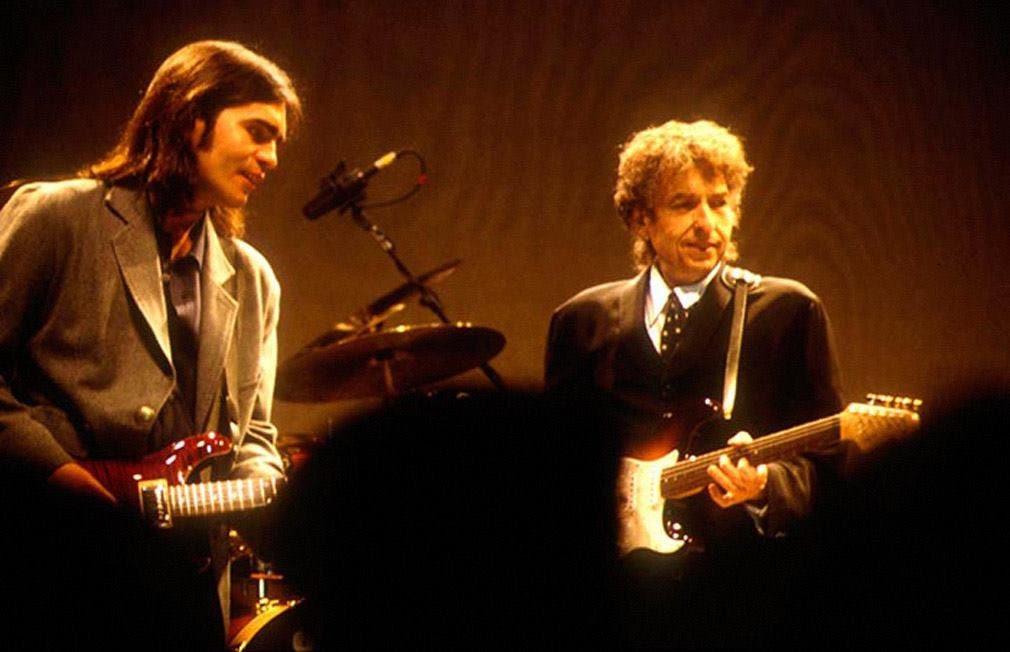

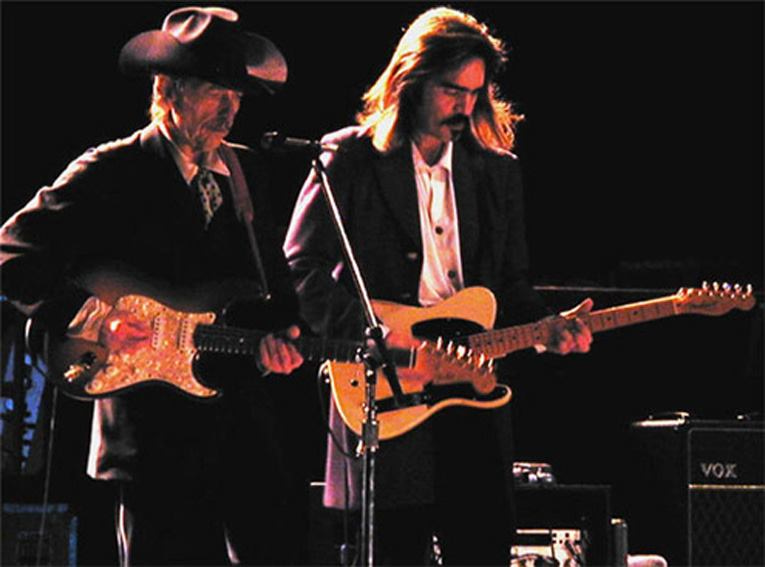

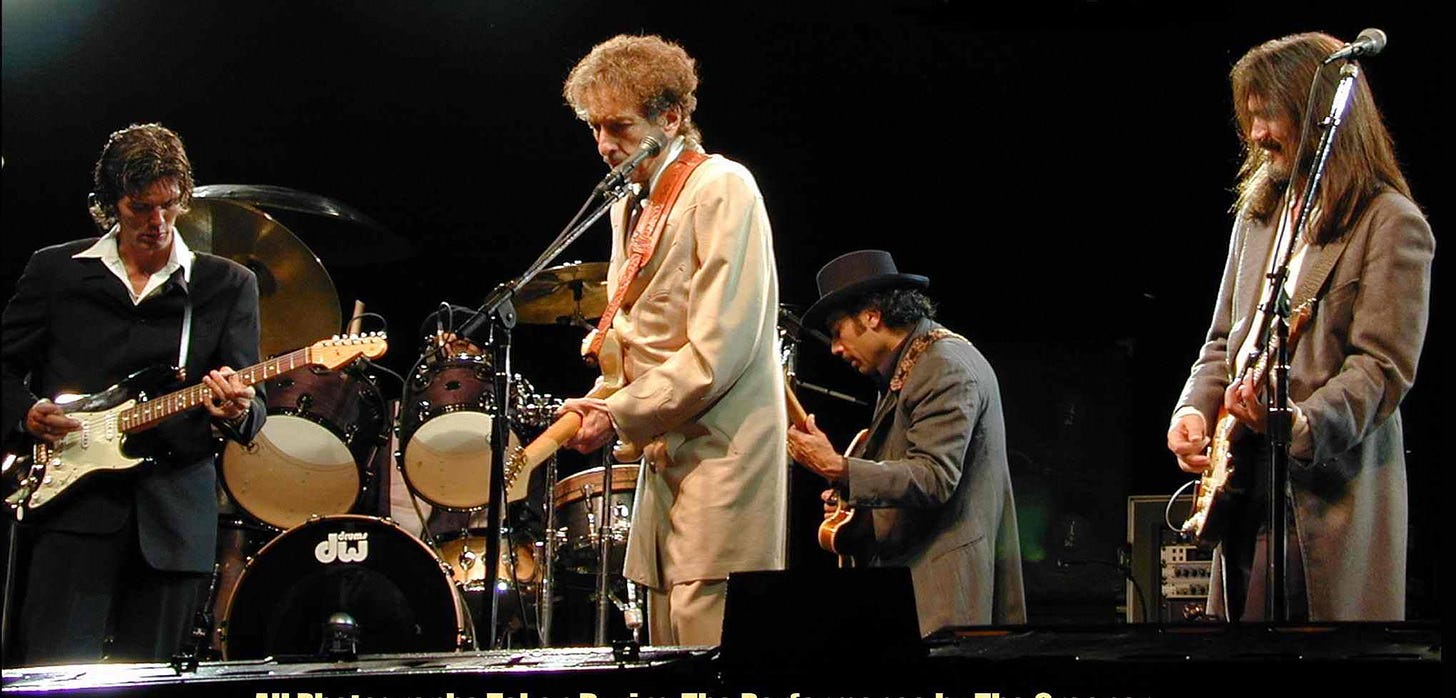

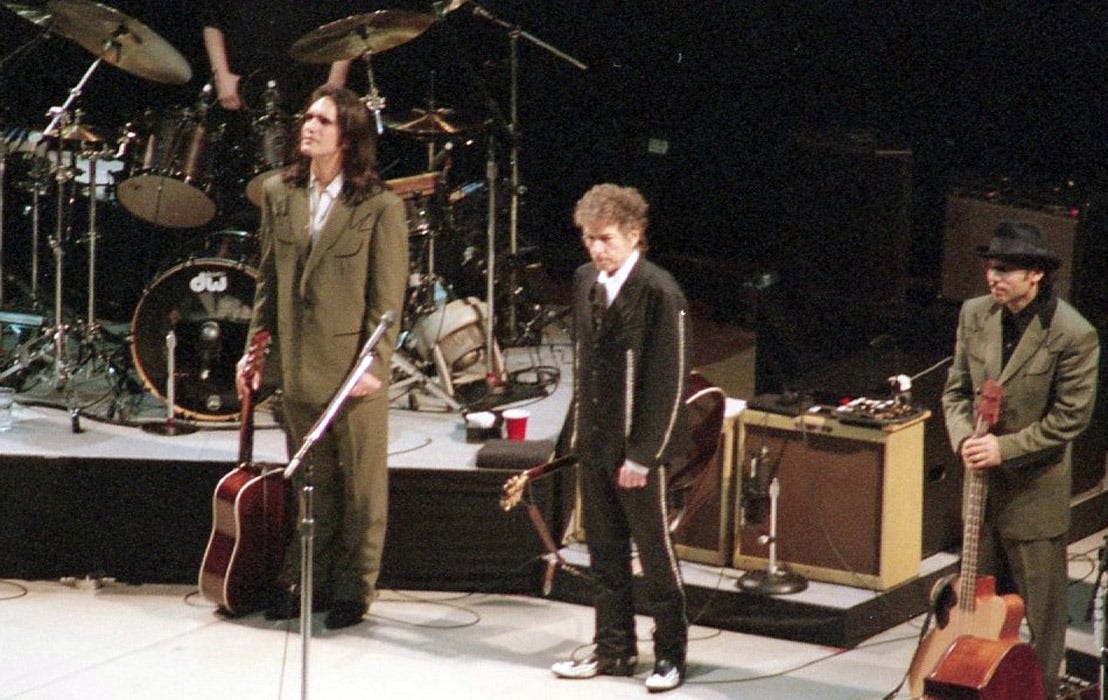

In 2013, Bob Dylan fan site Expecting Rain ran a poll to pick the best guitarist among the dozens who have backed Bob on the Never-Ending Tour. The winner? Larry Campbell. In 2016, they ran another poll. The winner? Larry Campbell. And then a third poll in 2018. Who won that time? Charlie Sexton…in a tie with his erstwhile bandmate and guitar-dueling partner Larry Campbell.

Larry Campbell played with Dylan from 1997 through 2004, and it’s a testament to Campbell’s career that’s probably not even the thing he’s best known for at this point. That would be his decade-long relationship with Levon Helm, producing his records and playing in his band alongside Campbell’s wife Teresa Williams. Since Levon’s passing, Larry and Teresa have continued backing up friends like Jackson Browne and Hot Tuna while beginning to record their own albums as a couple.

A new ten-part documentary called It Was the Music traces the path of their careers apart and together. I highly recommend it even if you mostly know Larry for his work with Bob or the couple for their work with Levon. Relix called it “a profound and moving work” and Americana UK a “fascinating and detailed look at the lives of two support musicians who take front of stage.” It’s available via Amazon and Vimeo. Here’s the trailer:

Today marks the 24th anniversary of Campbell’s first show with Dylan, and he recently got on the phone with me for an extended conversation about his eight years in the band. It’s a subject he’s been reluctant to talk too much about in the past, but he was willing to open up and share an inside look at what his world was like playing next to Bob all those years. Our conversation lasted so long that I’ve broken it into two parts. Here’s the first.

One thing the documentary makes clear is how deep in the roots music world you were before getting connected with Dylan. How did you transition from that career to playing with Dylan?

As concise as I can make this… There had been so much great music going on through the '60s that really spoke to me, from the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show all the way up through the FM radio, psychedelic music, Bob Dylan, Rolling Stones, all this fertile stuff in the world of rock and roll and popular music. I was really entranced by this music. I'd buy these Beatle records, and there'd be a song there by Chuck Berry. Who's Chuck Berry? Then I'd find that out. From Chuck Berry you go to BB King, from BB King you go to Albert King, from those guys you go back to Robert Johnson and all the country blues guys, and just keep going on that path. [The Beatles] did a tune by Buck Owens. Who's Buck Owens? From there you go to Hank Williams and George Jones and way back to the Carter Family. All this was overlapping with the folk boom. I couldn't get enough of this stuff. I was insatiable.

By the early '70s, I started to get a little bit disillusioned about what was going on in rock radio. I was really leaning towards the rootsier end of music. I decided New York City is not the place for me right now. I just packed up and moved out to California with some blind ambition. Long story short, ended up touring with a band, ended up settling in Jackson, Mississippi for a couple of years, where I really absorbed the culture of this music that spoke to me the most.

I ended up coming back to New York in the late '70s, just in time for this urban cowboy boom where country music was fashionable. It turned out to be a really lucrative situation for me because I was finding work in the studios and playing at clubs every week, the Lone Star Cafe, City Limits, all these places where this type of country music, the roots music that people were attracted to, was able to be performed.

One of the guys I had met in California - and we became very close in New York, he was on the same scene as me - was [longtime Dylan bassist] Tony Garnier. When I met him in California, [he] was the bass player with Asleep at the Wheel. He moved to New York just about the same time I moved back. We would play a lot of gigs together and studio work and all that. I just continued trying to be a New York City musician. I was playing in the clubs and touring with people like Doug Sahm, Rosanne Cash, kd lang, Cyndi Lauper. There's a long list.

So it’s the end of 1996 and I've decided I'm not going to tour anymore. I had just finished this tour with kd. I just wanted to be a New York studio musician and get more into producing records. A few months later, I get a call from Jeff Kramer, Bob's manager, saying Bob was interested in hearing me play and could I come down and hang and do some playing together? Bob's awareness of me came through my association with Tony Garnier.

I initially turned it down. I had made this decision, I wasn't going to tour anymore. Then I woke up the next day and remembered what my impetus for being in music was in the first place. It was the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan. I thought, "Wait a minute, I'm going to turn this down, this opportunity to work with this guy?" I called Kramer back. We worked it out. I came down, we played for about three days, and then the next thing I'm on tour for eight years with Bob.

You went from not touring anymore to touring with someone who tours about as much as any human being alive.

Exactly, yes. [laughs] That was a conflict for the whole eight years I was doing it. In fact, ultimately, that's why I left. I wanted to produce records. These opportunities were coming up, but I couldn't take advantage of most of ‘em, because I would try to schedule a day to do it and then we get called to go out on tour.

Playing with Bob is great. You're playing great music with this guy who's a total American original. Probably our best. But I still had this need to express myself. You could only do that to a limited degree when you're in this band with Bob, and it's completely understandable. There are parameters around your own personal expression. It has to be that way because it's his music. So that need was surfacing. If I was ever going to do this, I had to get on it. That combined with wanting to be with Teresa and wanting to be more of a studio guy and my own creative person, that's ultimately what got me off the road with him.

There's a moment in one of the episodes where Teresa's showing a photo of you guys on your 10th anniversary in Hawaii. She says, "Well, we were there because he was there with Bob." It got me thinking, your personal life too. If you're on the road eight, nine months a year every year – like, what personal life?

Exactly right. That's just the reality of it. That's the price you have to pay to do something like that. I was drawn to do it for as long as I could.

Getting back to the beginning of your time with Bob, Tony introduces you, you show up. Is there an audition process? How do you go from there to your first show?

Well, they weren't quite calling it an audition. Although, ostensibly, that's what it was. I showed up at the studio, and I met Bob, and we started playing. It was about three days of playing together. Mostly what we were playing was old rock and roll and country tunes. We do a few of his tunes, but it was mostly just running through like Hank Williams and Buddy Holly songs. It was a lot of fun. I guess Bob was absorbing what I was putting out. After that third day, Kramer called and said, "Okay, so we're going on tour next week. You coming?" I said, "Well, yes, I guess I am."

That first tour was Nova Scotia. We flew there and the boat with all the gear in it got stuck in the ice, crossing whatever strait that is. We're in Nova Scotia and all these dates are being delayed because the gear is not there. So that was a little nerve-wracking because I was ready to get into it, but everything worked out.

That first tour was great. We had rehearsed - not really rehearsed, we just played a bunch of music together, and then next thing I know, I'm on stage playing all these Bob Dylan songs, most of which I have never played before, and some I've never even heard before. You just jump in and do what you can do.

How are you learning those? Was someone giving you a tape like, "Here's what he played last tour. Go learn them."

No. I had a box full of cassettes of all his records. Once we got to Nova Scotia, I would just try to listen to his stuff as much as I could. In soundcheck before the first gig, we'd run through a few tunes that we would do that night, and that's the way the rest of the tour went. Most of the rehearsals for the shows were at soundchecks. Some tunes we would do, some tunes we wouldn't, and then there'd be songs that we didn't run through at soundcheck that we would just start doing. It was interesting! [laughs]

[Update: Hear recordings of two of those soundchecks here]

Did you feel intimidated being the new guy and stepping into the shoes of a bunch of iconic guitarists who have played with Bob before you?

I don't know if intimidated is the word. I was definitely on my toes, as I would be with any musical situation. Once you're up there doing it, if you've done it for long enough, you just fall into, "Okay, that's my gig. I got to do the best job I can do. I got to just listen to everything that's going on and react to it." I'm sure if I thought about it, and I probably did at some point, it was a pretty heady place to be. This is a guy that I've always respected as one of our greatest artists, and here I am six feet from him playing the stuff that made me respect him. I didn't want to mess it up, that's for sure. But you sorta fall into a professional mode. With any gig you're doing, you just put that hat on and it keeps you from freaking out.

Speaking of freaking out maybe, sounds like things are going great, then all of a sudden, one month in, Bob's rushed to the hospital, the next tour gets canceled. Do you remember when you heard, and what your reaction was?

We had played somewhere in the Midwest, and there was a dust storm. The dust was really thick. I was walking around the street, and I ran into Bob on his motorcycle. He was driving around in this dust storm. Apparently, the dust that was kicked up came off the river and had dried goose droppings in [it]. That's what he inhaled. I did too. I got a little sick also, but he ended up with histoplasmosis from that, which is a real serious thing.

I found out about it as we were preparing for the next tour, which was canceled. When I heard how serious it was, I mean, I just was hoping he would get better. I heard he was in a lot of pain, and certainly my sympathies were with him. I was concerned that nobody could give me a definitive answer about the potential for some sort of lasting or permanent damage from this. I was prepared for the possibility that that might have been my first and last experience with Bob.

Tracy Chapman called me because she heard that our tour had been canceled. I did a few dates with her during that time, waiting to hear about Bob. Fortunately, it all worked out, and he came back as good as new.

Do you remember the feeling or emotion at that first show back?

Oh, it was great. He was in good spirits, and we were all pumped too-- I think he began talking about wanting to do the next record at the beginning of that tour and that he was planning for a new record. I was excited at the prospect of doing an album with him.

At that second tour, I started to feel more comfortable. Bob was starting to venture into rootsier music, cover tunes, bluegrass and old folk songs and all that, which I thought was great because a lot of that stuff was really right in my wheelhouse. I think with that particular band it seemed like we were trying to color everything with a rootsy feel - which was highly satisfactory to me, I could tell you that!

I'm a huge fan of those recordings, the gospel tunes, the ones you were all singing together. How would those come to the band? Would Bob during a soundcheck suggest, "Here's an old Stanley Brothers song, let's work it up"?

Yes, that's pretty much it. Or he would give us a cassette [with] like three or four songs on there. "Hey, man, let's try this tune." We'd go back to the hotel, listen, and then come to the soundcheck next day and start working them out. He would hand out cassettes or he'd just pick a tune at a soundcheck and we'd see if anything came from it. We'd either continue and get somewhere with it or just drop it because he wasn't feeling it or something. It was a lot of fun playing these old Carter Family tunes and these Ralph Stanley tunes and folk songs…that he had played in his early days.

I wanted to ask you about arranging songs. Even his own songs could sound pretty different. Near the end of your tenure, I was learning guitar myself and I found this site that tabbed out that cool fingerpicking thing you did on “Girl of the North Country” - which, by the way, took me like two years to learn. For something like that, are you coming up with something and suggesting it to the band? Is he giving instructions, "I want the guitar to sound like X, figure something out”?

It’s all that. He would maybe suggest a riff for some certain songs. He'd play like a three-note riff, which I would grab, or Bucky [Baxter], or Charlie [Sexton] when he eventually joined the band, and then embellish on it - or not. I remember with certain songs he would say, "Let's play this riff every time after every verse." We would play that riff note for note.

In case of something like “North Country,” he would just strum his guitar and then I would play along once I knew where the verses were going and in a style that I felt would enhance what he was doing. Then [drummers] David Kemper or George Receli, they'd start with a groove. Bob may ask him to change it, or try something different, or keep this but change that. Everybody was throwing in with their own ideas, but we would also honor what he was able to explain. Very often he didn't even know what he was trying to get out of it. He just wanted it to land in a place that felt good to him. We'd kick each one of these songs around until it felt right. Very often nothing was ever completely structured initially. It was just, keep playing it over and over until we all find something that feels good.

Are these kicking around sessions mostly happening at soundchecks or are there more structured rehearsals as you went?

It would be soundcheck or a rehearsal before a tour. Normally, we would rehearse for four or five days before a tour. That would be a time we tried some new arrangement for a new song, but then it would keep evolving during the tour because we do these two-hour soundchecks, and very often just start working out new material in that time.

You mentioned Bucky Baxter [Dylan’s steel guitar player from 1992-1999] a minute ago, I was sorry when he passed last year. What are your memories of playing with him?

Bucky was a great musician, man. A really talented steel player and other instruments. He played great guitar and was just picking up fiddle [too]. I was showing him a bunch on the fiddle before he left the band. I really enjoyed singing with him, too, when him and Bob and I would sing together. It was a cool blend.

Teresa would come out on tour with us and be on the bus for a week or so, and we'd sit in the back lounge after a gig and just play old bluegrass tunes together with Teresa and Bucky and me. Mark Rutledge, who was the road manager, would bring out his dobro. We had this little semi-bluegrass band going in the back of the bus.

Did Bucky leaving change your role, in that you took on all those instruments you just mentioned he was playing? By the time I saw you [in 2004], you were playing a bunch of stuff.

Yes, exactly. Initially I was the guitar player and Bucky played steel. When he left, then Charlie came in. Charlie became the guitar player, and I would jump from guitar to fiddle to steel to mandolin to banjo. Charlie's presence in the band enabled me to do all the other things I can do, and Bob was trying to capitalize on that, which was cool although I had to be on my toes. I had some songs where I had just gotten comfortable with the guitar part, I had to suddenly change to a steel part or a fiddle part or something. But that's what I do, so I was able to do it.

This maybe won't be news to you, but, to the extent there is a fan consensus pick for best Never Ending Tour band, the one with you and Charlie I think gets mentioned more than anything else.

Wow, that's great. When our band was kicking on all cylinders, it was pretty hard to beat. I got to say there was good chemistry there.

Any particular favorite songs you enjoyed playing on stage?

Wow, that's a tough one. I loved doing “Summer Days” Man, to put one above another, boy, that's tough. I mentioned in our documentary series doing “Mr TambourineMan.” Playing that, playing “Blowin' in the Wind,” playing the iconic Dylan tunes when he was in it and giving it up. These tunes that meant so much to me when I was just learning about who I was. Those moments were really special.

The bluesier tunes were a lot of fun to play with him. “Crash on the Levee” and “Maggie's Farm” and “Serve Somebody,” that stuff was fun to play.

What about the blues stuff jumped out at you?

Bob is not an old Black guy, but he's got this authenticity in that genre that I don't know where it comes from. The blues comes out of suffering. It comes out of this experience that the African-Americans experienced in the United States that you feel like can only be really authentic if it's being expressed by someone who it had been handed down to through these generations of the Black American experience.

When Bob would sing one of his or anybody's blues tunes, he still found a way. Although it's not the Black American experience coming out of him, there's still something about his ability to do this. I felt the same way with [David] Bromberg, too. Bromberg, this big Jewish guy from Brooklyn, can deliver a blues tune with his own personal authenticity that gives him license to do it, and it was the same with Bob. How to define or explain that, I'm not sure. It's just a visceral thing you would get. A couple of the deep blues things we did on Love & Theft, when we would play those live, on a night when he's really giving it up, you just get this deep feeling.

What was a typical day on the road with Bob like?

Get into the hotel at 3:00 in the morning or whatever it is because we drive at night. Wake up, hopefully, after a few good hours of sleep. Get some food. Maybe, if you're capable, go to the gym before you do, and get dressed. Go to soundcheck. The band would warm up for a little bit for about a half-hour. Bob would show up, and then it would be another two hours of running through stuff. Maybe two hours on one tune, maybe a few tunes, maybe some songs that we would never play again. Soundcheck was always interesting that way. Then we break, go to dinner with catering. The caterers traveled with us. The food on this tour was unbelievable. It was the best thing about it. It was a catering company out of Knoxville. Oh, boy, that was something to look forward to.

I don't usually hear people raving about road food backstage.

I know, but everybody on this tour, all the crew, and the band, they did this right. We'd eat, and then chill for a half hour, and then do the show. That was the routine. Then, after the last song, off the stage on the bus right away. No hanging. On the bus and down to the next town. If you're lucky, it's a two-hour ride and you get to a hotel at a reasonable time and get some reasonable sleep, but very often it would be five to eight hours. Yeah, the road ain't for the faint of heart, man. It's pretty grueling.

After a show, was there any post-game recap or something where the band or Bob or anyone saying, "This worked, this didn't work, let's try this tomorrow"?

When we would get off the stage, there was a little curtained area behind the stage that was set up every night. We'd all get off the stage and go there. Bob would comment on whatever he wanted to comment about. "Yes, that was great." "No, that didn't work." "We’ve got to change this." That was pretty regular. Some comment one way or another. Then we would either address it at the soundcheck the next day or not.

Was that enough for you to go on? From the other musicians I’ve spoken to, some people find it frustrating. People feel like it's hard to read his mind.

Yes. I mean, Bob can be mercurial, for sure. You would think that you were giving him what he expressed that he wanted, and then the next day it could be the furthest thing from what he wanted that day. That would happen, but you just go with it. I think that could be frustrating but we can all be that way to some degree when you're trying to be a creative artist. That’s not uncommon. I think with our band, with Teresa and I, I might have been guilty of that myself a few times. It's just part of game, you know?

Was there a particular period that you look back on especially fondly?

There was a tour we did where we were doing some Warren Zevon tunes and we were doing some Rolling Stones tunes. When everything just started to click in a lot of ways. I can't remember what year that was. [It was 2002 –Ray]. Everything just felt like a smooth machine that tour. I don't know how to explain it or why, but the material we were doing, Bob's seeming contentment with everything, it just felt like we were all clicking.

What lessons did you take from your work with Dylan into your later work? Both with the stuff with Teresa and also playing with Levon, playing with Phil Lesh, and all the other people.

The big thing to me, and Teresa expresses this really well, an observation of hers from watching a Dylan show: If you feel it and you understand it, you don’t have to limit yourself to any genre of music. Teresa and I are really attracted to the same styles of music. She's a great country singer, she's a great ballad singer, she's a great folk singer, she's a great rock and roll singer, she can even be a great blues singer. She can do all this stuff. She always felt she had to choose one of these things and just be that, and to some degree so did I. After these years with Bob, we both felt like we had license to explore any genre we wanted to as performers as long as we had an affinity for that genre and respect for that genre.

We took this with us when we both started working with Levon. Levon could swing in any of these genres with total authority. Any genres that you call roots American music or what has become under the umbrella of Americana music, any genre that fits in there. And, of course, with Phil too. The Dead, those guys were all about taking these roots genres and stretching them to wherever they could go. Teresa and I were playing with Levon and with Phil at the same time. In fact, one of the tours was Phil and Levon and we were playing with both bands. With Levon, this genre-mixing was a little bit more of a song-structure way to do it, and with Phil, song structure was thrown out the window. It was just get up there, start playing, get in the song, and see where it takes you. To have these experiences with both of these guys was incredibly fulfilling. Then Teresa and I get to play with Hot Tuna, and their way of mixing all these genres, then we get to play with Little Feat and their way of mixing all these genres. It's a beautiful thing.

But back to your original question, this is what I got from playing with Bob. This concept of feeling comfortable in any genre that you feel attracted to and having a license to put all this stuff together in one show. That was something that was cemented to me from my years of playing with Bob.

But wait, there’s more! My conversation with Larry will continue. In Part 2, he tells the stories behind eleven of the most unusual performances he gave with Bob, for audiences ranging from the Pope to a shirtless man with “Soy Bomb” Sharpied on his chest. Subscribe here to get it sent right to your inbox next week [Update: Part 2 is here]:

In the meantime, here’s a download of Larry’s first show with Bob, 24 years ago today:

1997-03-31, Memorial Stadium, St. Johns, Newfoundland, Canada

Update June 2023:

Buy Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members, containing this interview and dozens more, now!

ICMYI

Turning Back the Clock [subscribers only]

1992-03-28, Entertainment Centre, Brisbane, Queensland, AustraliaPianist Alan Pasqua Talks "Murder Most Foul," Dylan's Nobel Lecture, and the 1978 Tour [free]

1978-03-27, Entertainment Center, Perth, AustraliaFreddy or Not [subscribers only]

2004-03-21, Kool Haus, Toronto, ONAfter Prague [subscribers only]

1995-03-14, Stadthalle, Furth, GermanyPlaying the Electric Violin [free]

2005-03-07, Paramount Theatre, Seattle, WA

You really take it to another level now, thanks a lot! There is probably a book in there.

Damn, Ray, you are on it. Great stuff! You are now the authoritative source for Bob Dylan live and in performance. And as this old reader of Paul Williams knows, that's the heart and soul of Bob Dylan. Very fine work.