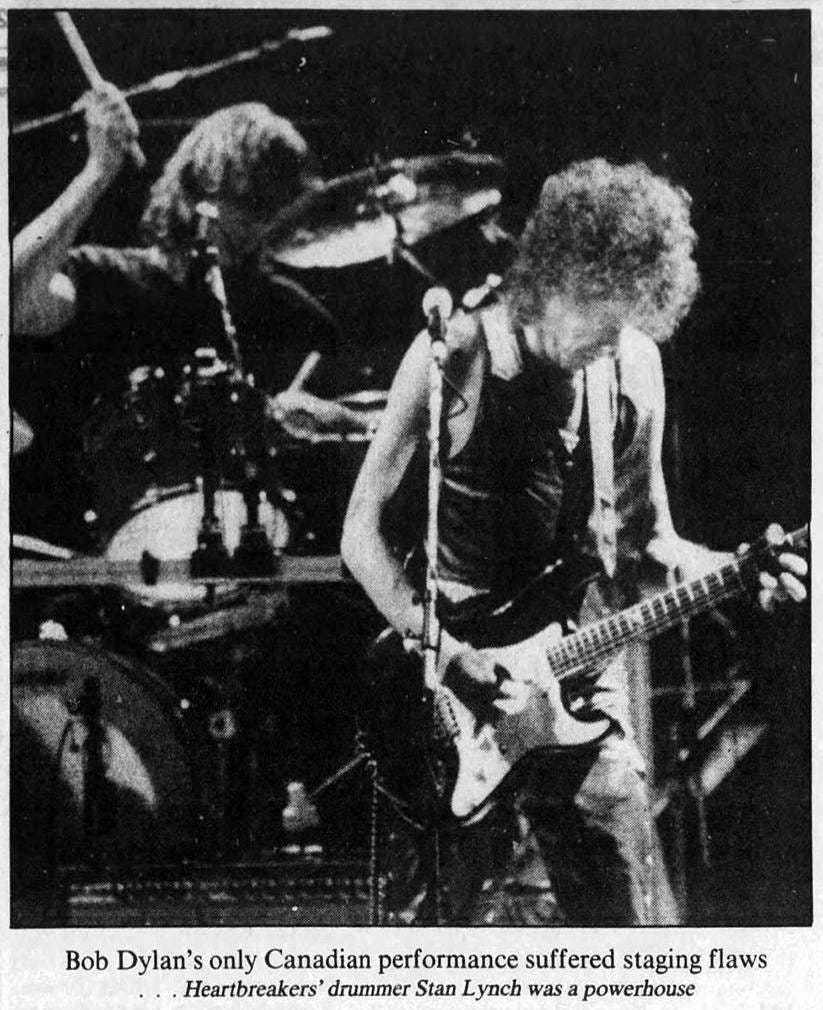

Heartbreakers Drummer Stan Lynch Talks Touring with Bob Dylan in the '80s

1986-06-09, Sports Arena, San Diego, CA

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

Update June 2023: This interview us included along with 40+ others in my new book ‘Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members.’ Buy it now in hardcover, paperback, or ebook!

To celebrate February’s anniversary of the first date of the first tour Bob Dylan did backed by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, I ran an interview with Heartbreakers keyboardist Benmont Tench. And today, on the anniversary of the first date of their second tour together, I am happy to present an in-depth conversation with the band’s drummer, Stan Lynch.

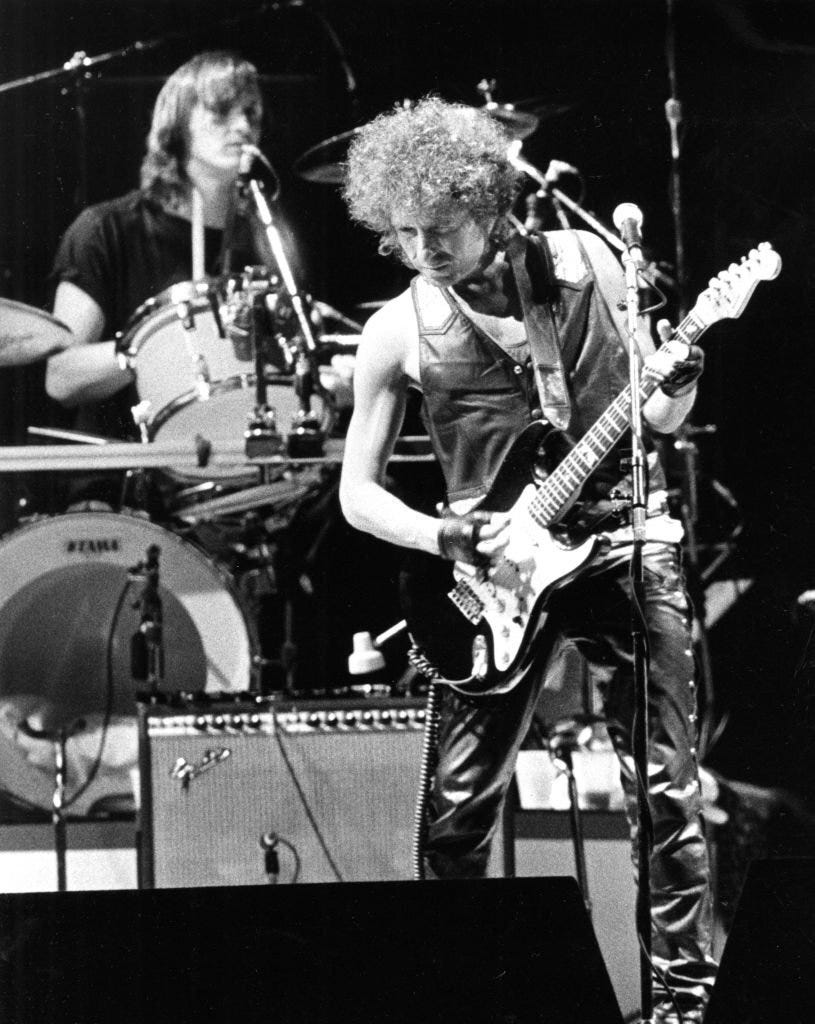

Dylan hired the Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers to back him for much of 1986 and then, following a few summer dates with the Dead, 1987 too. He later wrote in Chronicles, “Tom was at the top of his game and I was at the bottom of mine.” But Stan disagrees with the second half of that statement — and I do too. Those ‘86 shows in particular are about as fun as it gets, a joyful mix of hits and deep cuts and old-time-rock-and-roll covers, all backed by as a whitehot band as well as the Queens of Rhythm backing singers. As I’ve written before, it’s a personal favorite era of mine, and I was thrilled to talk with someone else who was on that stage.

To avoid too much overlap, I tried to ask Stan different things than I did Benmont. And, as Stan says, he brings a pretty different perspective than his longtime bandmate. He notes at one point, “I would love one day to be interviewed en masse and go around the room. Because then you'd get the truth. It takes everybody there to give you the truth. I don't know the truth. I just know what I think I saw.”

So when you’re done with this, read my equally long conversation with Benmont Tench, if you haven’t already, to get another perspective (and then, for a third take, my interview with former Petty and Dylan road manager Richard Fernandez). But, right now, here’s my conversation with Stan Lynch:

When I first emailed you, you said your experience was totally different from Benmont’s. Was there anything specific you were referring to?

There was a lot of pain in Ben's interview for me. That's how five guys can be such good friends and never know each other. Ben was very private, and I didn't realize he was struggling and how much personal pain he was going through.

I wasn't experiencing any of that. It was joy. The whole time, I was flying. My life was great, my body had never been stronger, no one ever to told me what to do or what not to do.

There was never a playbook. My joke was, I'm going to count four and then Bob is going to just start playing and, in about a minute or so, we'll know what song it is. It was glorious. I found the whole thing close to jazz. The front man is John Coltrane. I felt like Philly Joe Jones in those three hours. Everybody was just masters of improv.

Do you play?

Some guitar.

Do you know when you're having the best jam session of your life? One of those where you just go, "My God, I don't know where we're going, but this is really cool." It was like getting to jam, but the skeleton of the jam was “Like a Rolling Stone”! As long as you stick to the intentionality of that song, and you stick to the passion of the lyric, there was nothing you could do wrong from the drummer's seat. I just listened to Bob and did what he did. It was like serve and volley, punch and counterpunch. It was aggressive and exciting when it needed to be; it was beautiful when it needed to be.

The only time I knew I'd stepped out of line—there’s a great scene in Hard to Handle when I think I’m supposed to kick in, so I play this big drum fill announcing the band. And Bob just simply puts his hand up behind his back, without stopping the harmonica, and just shows me his palm. Which says to me, "Not now, kiddo. Back off. Save your rattlesnake bite for a later moment."

We'd probably done it a million times the other way, but I loved that you couldn't close your eyes and do anything by rote, ever. I found that to be so exhilarating. I never slept better in my life, because you were on your toes physically, emotionally. It was almost sensory overload to play with Bob.

Did you feel prepared for that, from your work either with The Heartbreakers or elsewhere?

Chaos is my middle name. I was born for anarchy and it's like, that's Bob! He's just a natural at it.

We're playing a big gig [one night]. I think three songs into it, Bob turns to me he says, ''Hey, Stan, what do you want to play tonight?" I'm thinking, "Uh, loaded question?" But I took it right at face value and, I went, "Well, how about ‘Lay Lady Lay’?” Because we'd never done it. I wanted to do that cool beat that's on the record, that beautiful mandolin swing. It just feels like mandolins are bashing into the wall. I really wanted to try that rhythm live.

That's how fearless you are. It didn't even occur to me that that might not be a good idea [to pick a song we’d never played before]. He says, "What key?" You never ask a drummer what key! I see Mike [Campbell] in the corner going, "A! A! A!" I go, "How about A?" Everybody has a big sigh of relief. Then Bob walks up to the microphone and proceeds to play a song I can't even recognize. Like, if this is “Lay Lady Lay,” I have no fucking idea, but it was fun as shit. It was the Ramones doing “Lay Lady Lay.”

The band was a little horrified maybe, but I was only horrified for about a second. I realized, "Well, we're really going with this!” We went with four minutes of “Lay Lady Lay” as a punk song, replete with the Queens of Rhythm all trying to find their way in. It was fantastic, but it was absolute anarchy.

Obviously by that point, you've got quite a comfort level together, but let's rewind back to Farm Aid 1985. First time in the room together rehearsing, what does that look like?

Fantastic. Interesting story, I think it was the first rehearsal. We were supposed to start at two and Bob showed up at five maybe. I already had tickets to see Frank Sinatra and Sammy Davis at the Greek. I'm a big fan. I remember saying around six o'clock, "I got to go." I just figured, fuck it.

Bob walked right up to me. He said, "Where are you going?” Like, what the fuck’s wrong with you? I said, "I got to go see Frank and Sammy."

The whole band backed away from me as if I had radioactive dust coming out of my ass. Bob took a big beat, and, God as my witness, he said, "Frank Sinatra? Sammy Davis? I love those guys!" So I took Bob as my date to go see Frank and Sammy.

What was your date like?

I was scared shitless. Like, he's in my car. Do I turn on the radio? What if Bob Dylan comes on? I think we just sat in silence.

We went to the Greek. Bob had the hooded sweatshirt on. Nobody really knows [he’s there]. I did somewhere between buddy and security, and we watched the show.

I think Sammy came out first, and it was fun as hell. I was probably stoned and just digging the show. Sammy ended and everybody stood up. Bob went to leave. He thought the show was over. I grabbed him by the back of the sweatshirt and went, "No, Frank's next!" "Oh, right."

I remember during intermission thinking to myself, "Gosh, I guess we should talk. That's what guys do.” And so we talked. He's just a guy. I figured, “Well, guys like to talk about motorcycles and girls.” So we did.

Then Frank came out. I'm watching Frank, and I'm watching Bob watching Frank. I'm just going, "Wow, this is a Fellini moment." We make it through the whole show, and somebody backstage figures out it's Bob. Somebody comes out and goes, "Frank says come by the dressing room after the show and say hello." I'm thinking, "Fuck, yes, this is going to be great!" I had a long-term love affair with the Rat Pack my whole life. It's been a thing for me.

So we go by the dressing room. I go, "Bob, over here. Let's go in and say hi to Frank." He goes, "Nah. Let's go."

So close.

It was so perfectly Bob. Like, "Nah, fuck it. I'm outta here." [laughs]

Love it.

Every time he was in the room, there was this energy. Talk about a guy who can read the room all wrong, that's me, but what I read was Bob was ready to have fun, play some music, don't stress, no posturing. Can we just make a joyful noise unto the lord? Every time he turned around, he would rock with me. If I was catching a groove, Bob did all the things that you want your frontman to do. Hips are swaying, shoulders are moving, he's looking at you and he's pointing. I loved every inch of it.

Did that come from day one, the band and him gelling like that?

Yes. I felt energy from him and freedom from him like I couldn’t even imagine.

The only fear I had was, I didn't want to disappoint Bob Dylan. I don't want to play something that he just thinks is offensive. But I figured he'd tell me. He was just that kind of guy. He'd walk up to you and go, "That’s a pile of dog shit." Fortunately, I never heard it. Matter of fact, I actually got some really nice “atta boy”s from him, that really, I didn't get that often.

Like what?

I remember one day he walked up right to the drum riser. I thought, "Oh, shit, I'm about to get it now. This is the moment I'm fired." I think all he said was, "Man, you're playing great right now. I love this." Part of me was wondering, "Is this a joke?” Maybe that's his way of saying you suck so hard I can't believe it. I figured I might get the call the next day from Elliot [Roberts, manager] and he'd say, "Hey, Bob thinks you suck.” I never got that call.

I loved what he did to the chemistry to the band. It just changed the dynamic. You add a sixth member on anything— oh, and that other guy is Bob? Like, "Well, this is dynamite in the baby carriage right here. Carry it carefully." We were all very reverent. I saw it immediately in the other guys too. It was like, "Oh, shit, we're in the presence of somebody who can really do this!" We thought we were seasoned vets, and we realized, "This had been pre-cooked way before us. He's been good a long, long, long time."

What do you remember about that first actual show, the Farm Aid one months before the tour?

I don't remember much except I think we did “Maggie's Farm.” It was funny as shit, because none of us really knew what was going to happen.

I think Willie Nelson came out for that too.

I was probably shitting my pants. I was probably going, "Wow, this is a Wayne's World moment for me. I'm playing with Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson and Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers!" You just go, "Pinch me. This is the kind of shit I dream about, and it's happening." I was pretty much in that mode for my entire rock career. I never could believe it. I was just going, "Holy shit!"

I found him to be very likable. I hope you can convey in this interview the big grin on my face when I think of Bob Dylan. That's why I said Ben and I had very different memories. I was experiencing zero pain — physically, emotionally, spiritually. I was only experiencing joy. I'm getting to play amazing songs with amazing musicians in amazing places all over the freaking world. It wasn't like, “Oh, yeah, you're playing Spank, Idaho." You're going to go to New Zealand, you're going to go to Australia, you’ll be playing in East Berlin and all over Italy. It’s like, "Oh, fuck!" He's universal. Bob speaks the universal language of brilliance.

You mentioned Australia. One of the things you did there was record the first Heartbreakers/Dylan song, “Band of the Hand.” Do you remember anything about that?

It was quick. I think we learned it in the studio. You can hear me trying way too hard, because I'm still in live mode. I'm like, "I'm not making a record, I'm making a live document of our aggressive fabulousness.” I probably came in, beat the shit out of my drums for a couple of hours, and they said, "Get outta here." [laughs]

You’ve got The Queens of Rhythm singing backup too. Dylan had been doing stuff like that in the gospel years, but was that new for you and The Heartbreakers?

I'd never experienced anything of that caliber. They were fabulous. They also played rhythm, tambourines and shakers. They were bringing the church to this shit.

What a show for me, because I got the best seat in the house. I'm looking to my left and there's those wonderful women just physically involved with the music. I look to my right and it's Benmont and [Heartbreakers guitarist] Mike Campbell, and I looked to the front and it's Bob Dylan and Tom Petty. It's like, shit, everywhere I look, it's great.

What does it look like when you're not on stage? Are people hanging out together during the off-hours or keeping to themselves?

The camps were pretty established. There were nights in the bar you'd see everybody. You never knew who would be there. The people that Bob attracted, and the people that were coming to me with stories about, “Oh, I was Bob's masseuse. You have to tell Bob that Joe said—." I'm getting like five of those an hour.

There was one show we did where it finally hit me. I wasn't the sharpest tool in the shed with music back then. I was very self-absorbed, as many young musicians are. Then when we were in Italy one night, I remember I really heard Bob Dylan. I heard him.

Usually when he did his solo stuff, I was like, "Well, if I'm not involved, I'll leave." But I was sitting there at the drums still. I sat behind the kit and I smoked a cigarette and I watched this man. It's one guy, one guitar, and he's singing “Blowin' in the Wind.” I melted. I cried. I started to actually weep because it hit me in that one moment finally. Like, this guy wrote all this stuff and he’s doing it tonight. It's pouring out of him like sweat. It feels effortless, but it's killing me. Every line ripped me to shreds. He did a song, I wish I could remember it. It was about a young man who volunteers to go to war and he comes home with the medals.

“John Brown”

Yes. He puts the medal in her hands. Just thinking about it now can choke me up. That was the moment I was never the same on the tour again. I was never the same. I remember walking up to Bob at the end of that show while we were all still sweaty. I put my hands on his shoulders and said something like, "You really fucked me up tonight." He looked at me with that billion-dollar look and he said, in that voice, "Stan…are you all right?" Like he didn't understand what I was saying to him. What should have come out of my mouth was nothing, but, of course, being me, I had to say something. What came out of his was like, "No, no, not you!"

It was strange. I don't know if the relationship— I'm not saying we had a relationship, but I looked forward to seeing Bob. I loved talking to him. Everything you say to him, whatever came back was not what you expected. I remember once saying something like, "Wow, I love that outfit." He said, "Yeah, what do you like about it?" It wasn't what I expected. You’d expect like "Thanks man" or whatever.

Bob was fantastic at keeping you on your left foot all the time. I did not find that uncomfortable, I found it growth-inspiring, exotic, enticing. Challenging, in a good way. Like, "Bring it."

Did you have any favorite songs to play, either ones you did every night or something you did once or twice?

“Positively 4th Street” used to blow my mind. “Like a Rolling Stone” blew my mind. “Knockin' on Heaven's Door” blew my mind. I'd have to look at the song list because probably every freaking song I go, "What??" For me it was hard not to just be excited to be there every second. How amazing to know that I'm going to play three hours of songs that are etched in my soul. At one point Roger McGuinn comes up and sings “Mr. Tambourine Man” in front of hundreds of thousands of people in East Berlin. The place looks like a sea that's going to erupt. Even at the time, “This is going to be an apex moment. This is a zenith.” I felt it. “From here on out, it's going to be a letdown.”

I miss it. If there was ever a part of my life I could relive, that might be it. The rest of it, I'm cool. I'm glad I did it. That's one I would like to do again.

You did some shows with the Grateful Dead, big stadium shows in the US. Do you remember anything about touring with those guys?

Once again, I had a completely opposite experience as Ben. I was not a fan, so I didn't care. The guy you're talking to now knows what a stupid thing that is to say. The man you're talking to now, 30 plus years later, knows what an idiot that kid was.

You didn't know me then, but I was more of a hedonist. I was like, "I'm in a rock and roll band and all of that implies. Take no prisoners. I want it all." That was me. I was not really a session guy or a guy that wanted to be taken lightly or not noticed. I had a big mouth and I played a lot of drum fills and probably made way too much noise coming out of my mouth and my drums. Fortunately, everyone was tolerant.

To me, what's so special about these tours, and I think I said this to Benmont, it's like the most pure fun you can hear at a Dylan show. Even the great Dylan shows, sometimes “fun” isn't the key word. A big part of that is you driving it forward, hard and loud and having a blast. I think it comes across even if you're just listening to a bootleg.

I played those gigs as ferocious as I was capable of. Most drummers will tell you, "Never go to 10." If you go to 10, you blew your wad. But I did. I went all the way. Benmont went with me too. Everybody did. Everybody was fully willing to engage. When it was time to throttle up, it was all the way.

You mentioned McGuinn. I was looking through the setlists, you had so many people sitting in. Stevie Nicks, Mark Knopfler, John Lee Hooker, Ron Wood, Harrison. Any good stories about anyone else?

Where was John Lee Hooker? Was that in San Francisco, with Al Kooper there too?

Yeah

It's a story. It's not a good story. Maybe I'll hold onto that one. That was a bad night for Tom and I. Tom and I had a very, very bad night. We argued terribly. John Lee Hooker and Al Kooper came out and saved us from being assholes. That's about as nice as I can put it.

The presence of outsiders got you back on your best behavior?

Actually, it was probably a turning point for Tom and I. We never recovered from it, but the evening was saved by the presence of greatness. I love Al Kooper. He's essential. He's just essential in so many careers, including mine. He's a loadstone and he doesn't even know it.

It's funny you mention him, because Ben told me that he knew the Al Kooper parts on stuff like “Like A Rolling Stone” and was playing off of those. Did you have an equivalent? Were you thinking about the “Positively 4th Street” drum part or Sam Lay or—?

No. That's what's so pathetic! That shows you the absolute arrogance and profound stupidity. It wasn't until after the tour that I started hearing what the records really were like. I don't think there's one thing I ever did with Bob Dylan that was ever from the record, except maybe…let me think… No, I fucked up everything. [laughs]

I had no clue what anybody did. Never studied a record in my life. I probably actually thought that's what the record sounded like. I'm not sure if idiot is the word. Ill-informed. The fact that that guy was tolerated is extraordinary.

Obviously you knew the hits at least. Did you know the deeper cuts?

No, I didn’t. I owned a few Bob Dylan records. I loved them, but I never studied them. All I knew was, I loved the way he sounds. When everybody would tell me like, "Bob Dylan can't sing," I'm going, "No, he sounds cool as shit." I loved the way he looked, I loved what he wore, I loved his record covers.

He was a cult figure to me that you could never know, so I didn't really bother trying. I didn't really think about his life, or the depth of it. I was young and dumb, man. A rock and roll fan. I loved what I loved and Bob was part of it. I loved Steppenwolf too. I was more like, "I wonder what kind of chicks Bob gets. I wonder what he drives."

I've got a few couple specific shows in the later stages of your two-year run to ask you about. One was the opening of your final tour in Israel. It was a big deal at the time, him playing there. What do you remember about that?

I remember the security. They literally carried scimitars on their belt. I said, "Why do you carry that instead of a gun?" He said, "A gun's great from a distance, but up close a gun is worthless. With this, if you get close to me, you're mine." I went like, "These guys are serious. They'll just rip my entrails out."

I remember going to a Seder; I think maybe the Prime Minister put it on. I remember Bob being there. I remember talking to girls on the beach and thinking they're going to be knocked out. “I'm here with Bob Dylan!” Then I said, "What do you guys do?" "We're in the military. All four of us are aces with confirmed kills. We're going to be working tonight." I'm like, oh, right, okay. There's reality. On stage, I was pretty emotionally blitzed. That was the most somber moment of my musical life.

I remember being on my balcony in the Hotel David in Tel Aviv. I smelled smoke, so I called down. By the time I hung the phone up, two armed military show up with 9-millimeter sidearms. This is serious shit. They push me aside, literally, and walk to the end of my balcony. They walk out and they smell and they look. They turn around and they go, "It's nothing, just a garbage fire. Thank you for calling."

They take that call seriously.

Fuck yeah. Here's what I else remember. We went to a disco in Israel. You know, going out partying. Come home late. The hotel lobby’s dark. It looks like it's locked. You can't see a thing. I'm with the guys and they're complaining. "What the fuck man. Who turned the fucking lights off?” I walk in and my eyes adjust. There's six fucking military men with Uzis in all four corners in the lobby, just looking at us.

That's the beginning of the ‘87 tour. Then the end of the tour, grand finale at Wembley, a whole bunch of special guests. Anything you remember about those shows?

I got to meet Ringo. That's a great drummer moment. Oh God, I shit my pants trying to come up with something funny to say and blew that too. I tried to thank him for everything. What came out of my mouth was something like, "I want to thank you for my haircut and my car and my—" I don't know. I was completely sideways. He just gave me a big hug and went, "I know. I know." Because every drummer just craps their pants when they meet fucking Ringo. What would I be without that first Ed Sullivan show? A plumber?

I would gladly wear a True Confessions tour t-shirt today. I've tried to meet Bob. I've gone to several shows and never been invited to come say hello. All I could say would be, "I love you. Thank you. I hope you have any good memories of anything I contributed to your life at all. If you even remember it." It was so memorable for me. It's as memorable as your first girlfriend.

You have that Sinatra story. Do you remember any other outings along the way with Dylan?

I have endless hours of film footage of it, 8mm, and I've yet to sit down and watch it. I have hours and hours.

I remember going out to Sydney Harbor with Bob. Somebody had a sailboat. We went out and we anchored off a little island. I remember thinking I'm going to go in and take a swim. I jumped over the side. The next thing I knew, Bob jumps over the side, and we both took off swimming. We swam for the island, and we made it. There was a rope on a tree. I said something like, "You want to climb the rope?" "I will if you will." So I climbed the rope, and Bob climbed the rope. I think the people from the boat said, "Do you want us to come and get you?" I said, "Bob, you want to swim back?" "I will if you will." So we swam back to the boat.

To me, that's my takeaway. Everybody thinks they know Bob Dylan. I think I know my version. It was very simple. "I will if you will" kind of says it all to me. That's the experience I had with him on stage. I said that to him musically, every chance I could, "We going to do this?" "I will if you will.”

One thing I wanted to hit on not related to this tour is the 30th anniversary concert a few years later, in 1992. You’re onstage playing with Jim Keltner. How did that happen?

That's just good fortune. Somebody might have said, "Is it okay if Stan plays?" and Jimmy's like, "Yeah, sure." That's another one of those, with what I know now, could I have taken real advantage of that? I just sat down and blew thunder out my ass. I didn't listen enough. Jimmy Lee Keltner, that's the mother church of rock and roll drumming right there.

Yeah, I spoke to him last fall. He's the best.

There's not a cooler guy. There's not a groovier guy. There's not a more soulful guy. If he would adopt me, I would move in. There's nothing about Jim Keltner that you don't want to emulate.

I didn't play but maybe one song. I did shake the tambourine on “Mr. Tambourine Man.” I do recall that. I remember thinking, "I am Mr. Tambourine Man." [laughs]

There's some good photos with you perched up there where it's the grand finale with everyone.

What am I doing, playing a tambourine?

You might be. I got to look.

It's not much. I remember thinking, "The world doesn't need another drummer right now." I did get a cool attaché case that says “Bob Dylan 30th Anniversary.” That still sits in my storage locker

Remember, I haven't been in The Heartbreakers since 1994, so just to even say, "Yes, I played in Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers, and we went out with Bob Dylan," that's great! So much has happened since then for me, musically and cosmically. I've had two more careers since then. But that one, it's pretty cool.

Not a lot of people can say that

It was fun to get the stories. Once I got in a dressing room with Ronnie Wood and Garth Hudson. I remember Ronnie walking in and going, "Stan, want to smoke?" He had two packs of Marlboros. I go, "I don't smoke." He flung one at me and hit me in the head. "Take it up then."

Then he goes, "Stan, what are you drinking?" "Water." "Water? What's that like?"

These guys never let me down. They never fucking let me down. Bob's brilliant. A guy like Ronnie Wood, I've idolized him since Jeff Beck records. Shit. It's like you go, "Wow. I wonder if they'll let me in."

The same with Roger McGuinn. We toured together; I made a record with him. I can't tell you how many times I stared at every Byrds album cover and listened to the records with headphones on. Then the fact that he's standing right in front of me, and he'll let me in— I always felt like the redheaded stepchild with a lot to prove. If they'll let me in the club, I'll try to prove that I'm worthy to be there musically, and more importantly be a good hang. I won't be a drag.

Like I said, that's why it took me down a few pegs when I read Ben's interview. There was no place else I wanted to be. I could see Ben, he wanted to be home. For me, the road was never a place to dread. You hear the other guys and they go, "Oh, fuck, how many weeks are we going to be gone?" I'm going, "Shit, pack my suitcase for the next 10 years, I don't care!" It's an adventure. Literally, the first time we went to London back in the '70s, I didn't come home. The band said, "We got six weeks off. We're going home.” I met a girl and moved in. I lived in London until I had to go.

Rock and roll is a litmus test. It's a mirror. If you smile at it, it smiles back. If you shit at it, it shits back. If you're angry at it, then it's angry at you. That's how I felt about audiences. You're in front of 15,000 people, and, if you're an asshole, you probably deserve to be booed. That’s what I never understood. Even in the old days, it would be like, "Why are you bringing a bad attitude to people who just shelled out a lot of money and showed up?" Just never made any sense to me. If you're in a bad mood, you should probably get your ass in a good mood. “Hey, man, everybody knows the road sucks.” Fine, but does it really, or do you suck?

Were The Heartbreakers changed by the tour? After '87 ends and Bob is now removed for the equation, are you performing differently on your own tours and recordings?

I thought the band was going to continue to be that great and sound like that for the rest of my life. It didn't. When the tour wrapped, I probably figured everybody felt the same way as me, that this is so fucking good it's going to be like this always. And boy, was I wrong. That's probably where it started. Everything shifted for me right around then, I think.

You were on different tracks coming out of it?

Completely. There is a joke about five guys touching an elephant. You know this one?

I don't think so.

Okay, five blind men discover an elephant. They all are touching it, and they're all describing it, but they're describing something completely different. One guy's got the trunk, and he's going, "It's probably a snake." One guy's holding the ear, one guy's holding the tail, one guy's touching the foot. It's five people describing an elephant.

That's how I would describe the end of that tour. I walked away thinking it was the coolest thing I've ever seen in my life. The other people walked away probably going like, "Thank God that's over." I would love one day to be interviewed en masse and go around the room. Because then you'd get the truth. It takes everybody there to give you the truth. I don't know the truth. I just know what I think I saw.

I loved everybody in the band. They were my brothers. Everybody was on their toes. They were laughing. You couldn't take it seriously. [Bassist] Howie Epstein and I couldn't keep a straight face 90% of the time, because we were so enamored that we were actually making it happen. You couldn't pose. You couldn't go strike a shape and think anybody was going to believe that shit. You couldn't play at rock star when you're playing with Bob Dylan. You just fucking get out there and knock the music down.

That's what I thought everybody in the band was doing. Benmont Tench, get the fuck out of here. That guy, you put a hand behind his back, it still is going to be magic. He'd make shit out of smoke. Mike Campbell, if you look at his hands, you can't even tell what chord he's playing because he knows so many. I got no fucking idea what he's doing, but Jesus, he's that good. He owns 21 frets. He owns them. Like they're his bitch. And then he's listening to Benmont, and he’s sending him off into another direction, and the two of them are making music out of G, A, and D that you've never heard before in your life.

If ever I needed to be musically entertained, I just put my right ear over [to them]. If I ever I wanted to be biologically entertained, I'd look at Tom and the Queens of Rhythm and Howie. This is some foundational shit right here. It's like not cerebral. This is from the waist down. Rock and roll has to entertain you from the neck up and the waist down, you know what I mean? The right side of the stage is entertaining me so heavily, and the left side's got my balls in a sling, and I'm just going, "This is rocking me." And then, oh yeah, by the way, it's Bob Dylan! Like there's a crown on top of the whole fucking thing. So did I enjoy myself? I reckon I did.

Do you think any of that has to do with the fact that it wasn't a Heartbreakers tour? Was there less pressure, not doing your own songs the entire night?

Nobody wants to think of themselves as being in a backup band. Even when you're in The Heartbreakers with Tom, we never wanted to think of ourselves that way. You never had the freedom of just being a backup band. You could be responsible for the crash of a gig.

With Bob Dylan, and Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers as the backup band, you couldn't crash the gig. I mean, Bob Dylan doesn't need you there anyway. He proved it every night by going out and playing four or five songs on his own that were like, “Oh my God!” So the pressure was never really on the band. You're right, I think there was a little air out of the balloon. I didn't own those charts. The thing with Petty and The Heartbreakers, I own those. If you're playing “Refugee,” it's got to sound like fucking “Refugee.” If it’s “Listen to Her Heart,” I’ve got to sing that shit. With Bob, I didn't own any of those charts. I didn't even fucking know ‘em, I'm so stupid and belligerent. As long as I'm just bringing some heat, there really was no pressure.

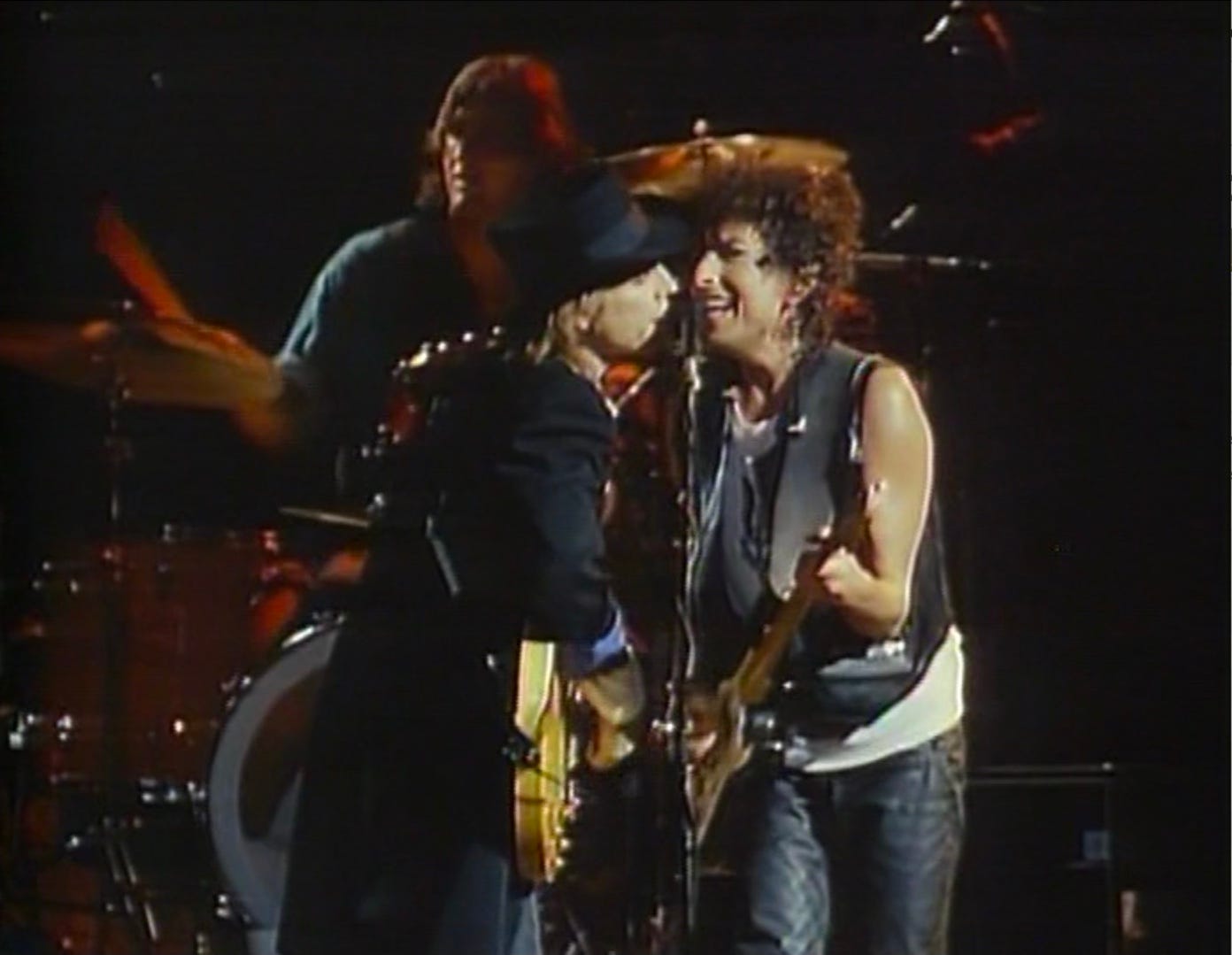

To a man, woman on that stage, they were all extraordinary. It was a very fortunate convergence that all came together. You couldn't plan for that. It had all the things that great theater has, but all there for a reason. Tom sang together with Bob on one mic. They never rehearsed that, ever. When Tom would do, "How does it feel?" he’d be on one mic screaming with him. If those guys had bad breath, they knew it. They were smelling each other’s tobacco. We all were. It was so intimate and so real.

I remember starting a song once with some stupid beat. Bob started playing something reggae, and I decided, well tonight I'm going with— I got about four bars into it. It's the only time he ever did it to me, he looked at me and gave me the international “No.”

What do you mean?

He took the cigarette and butted it out on the floor, and did the thing under his neck, where he went like, "No."

Like, cut it out?

Yeah. Like, that's not going to fly. Don't make me commit to that for four minutes, you idiot. I was a little insulted for about a half a second, and I just went "Riiiight. That's a terrible check to try to write for the next four minutes." Because once a drummer puts his foot down, this is where it's going. And sometimes I was off. Sometimes I was probably off by a fucking country mile. Usually the band would always just honor it. They would go like, "Okay, Lynch has spoken. Let's go."

I read somewhere that Bob didn't think he was that good during that time. That broke my fucking heart. It literally reduced me to like emotional rubble, because I thought the motherfucker brought the shit. I'd never seen anything like it. Not that he’d ever want to talk about it, but if I had a chance, I’d be like, "God, I read somewhere that you thought you weren't bringing it? Man, you have no idea how inspiring you were for me. You never let me down."

Thanks to Stan Lynch! A couple months after we spoke, Stan reunited with his old Heartbreakers bandmate Mike Campbell for the first time in decades. Read about their recent tour together in Rolling Stone. Thanks also to Matt Wardlaw for connecting me with Stan.

1986-06-09, Sports Arena, San Diego, CA

Update June 2023:

Buy my book Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members, containing this interview and dozens more, now!

What a great interview! This guy sounds like the coolest man on the planet, and exactly what Dylan would want in a drummer. Rock and roll is a mirror--I'm gonna keep thinking about that one for a while. Great stuff, Ray.

It's a shame that he didn't go into detail about what happened between him and Tom. I was always curious but never able to find out.