Harvey Goldsmith Talks Promoting Bob Dylan Shows at Blackbushe, Real Live, and Bobfest

'Real Live' Promoter Interviews #3: Harvey Goldsmith, UK

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

I’m not sure how many concert promoters were ever named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) by the Queen herself, but it has to be a short list. One is Harvey Goldsmith. Hell, the man hangs out with both types of Queen:

Before all that though, Goldsmith worked with Bob Dylan, promoting many of his biggest shows in the UK. That includes the two enormous UK shows on Dylan’s giant 1984 tour with Santana, at Wembley Stadium in London and St. James Park in Newcastle, from which all but one track on Real Live was taken. So I called him up for the third and final entry in my ‘84-promoter series—find the first two here and here.

He’s worked with Dylan many other times as well, so we discussed all the rest too. That includes the mammoth Blackbushe 1978 show Goldsmith oversaw, the largest concert of Dylan’s entire career; Live Aid, which Goldsmith helped organize with Bob Geldof and where Dylan gave a famously dire performance; and the 30th anniversary celebration (aka. Bobfest), where Dylan personally asked him to help save it from disaster.

Oh, and the time Bob chewed him out for leaving a show early.

Before we get to 1984 with Santana, was Blackbushe 1978 the first time you had worked a Dylan show?

Of any scale. I did Earl’s Court before Blackbushe. We did six nights at Earl's Court, and then we did a tour of Europe, and then we did Blackbushe. Earl's Court is a huge space, 18,000 people. And we sold out six nights in a heartbeat.

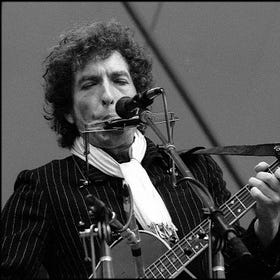

What do you remember about the performances?

When we did the Earl's Court shows, every single night was stunning. Probably his best band ever. Every major person in the UK came to see it, including Princess Margaret, who came twice. The Aga Khan came. It was just one of those.

That whole run of shows was really quite incredible. He was in such top form. That's why we extended the tour to Europe and then eventually did the Blackbushe show.

That ‘78 tour was the first time he'd really toured the UK since the motorcycle crash a decade-plus prior.

Yes. He was managed by Jerry Weintraub at the time. I phoned him and said, “I'd like to come over and talk to you because it's time for Bob Dylan to go on the road.” He said, “What makes you think that?” I said, “Because it's time.”

I went over to see him. We had this meeting in Jerry's office, and in walked Dylan. I must have had a sixth sense about it. It was the right time.

Was that the first time you’d met Bob?

I met him when I was managing Van Morrison, and he and The Band put The Last Waltz together. We hit it off. That’s kind of how it all started. Van and Robbie sat down and helped put the show together, the structure of it. It was quite carefully crafted. They worked out very carefully who should go on when, so one would not upstage the other. So I was spending quite a lot of time with that, and Dylan was dipping in and out. We just kind of got on.

I didn't realize you were managing Van. He practically steals the Last Waltz with that performance of “Caravan.”

If you look very carefully at the film, when Van goes out, you'll see a foot behind him pushing him on stage. That's my boot.

He didn't want to go on stage. He had a panic attack just before he went on. When he got out there on that stage, he just killed. I mean, he was just unbelievable. Van went on after Neil Diamond, and the audience were really revved up. By the time he got out, I think he picked up again, the vibe of the audience and just went for it.

Was stage fright typical for him?

All artists get stage fright. Some show it more than others.

So tell me about the giant Blackbushe show.

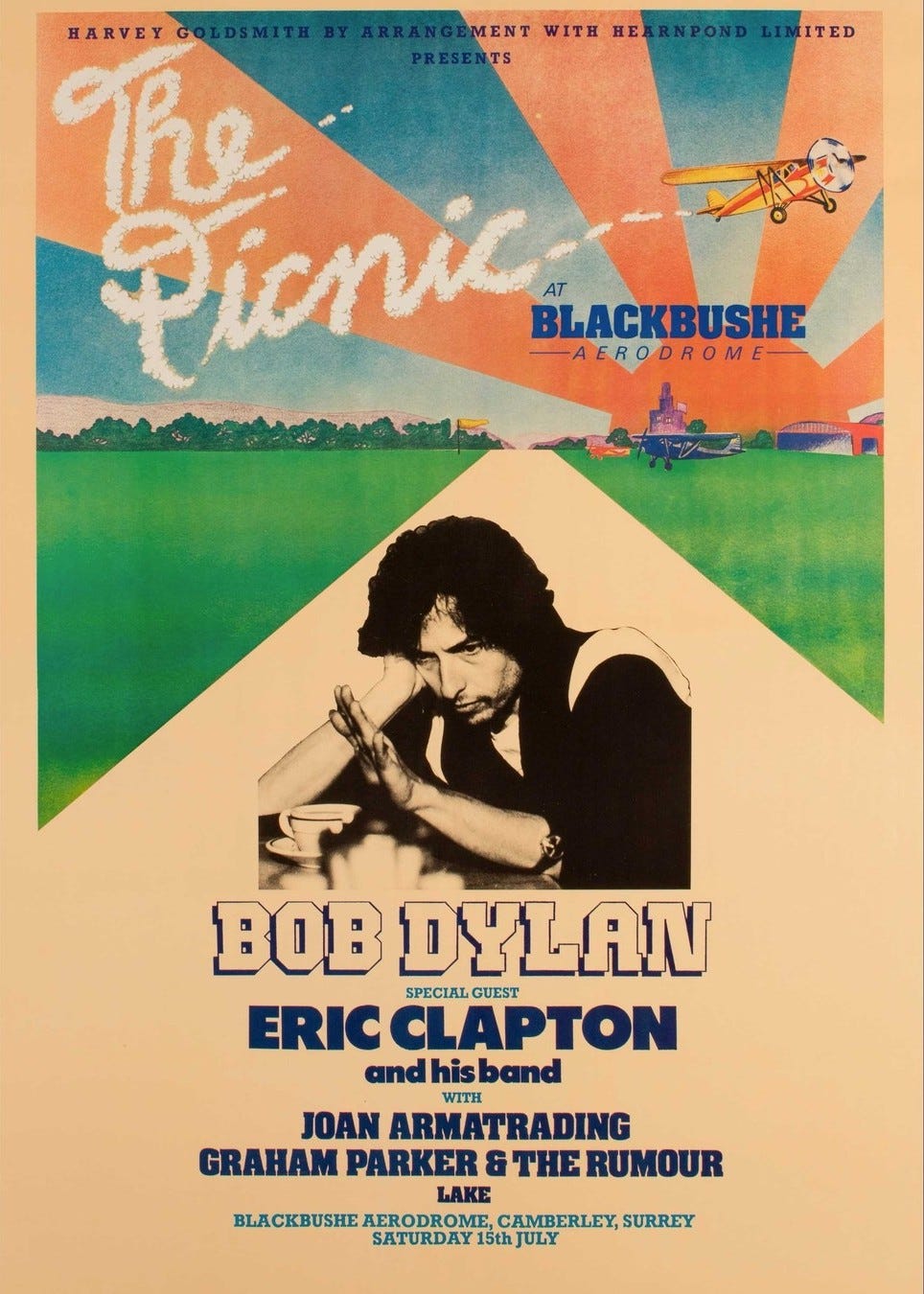

Blackbushe was a complete punt. I think I paid the largest amount of money to an artist ever at that point in time. I guaranteed him over a million pounds, in which case they couldn't say no. I just stuck my neck out because it was just catching the feel, the vibe of what was going on at the time. I just thought, “Let's go for it.”

But we had such a great bill. We had Eric Clapton. We had Joan Armatrading. We drew one of the largest open-air crowds ever in England. Over 175,000 people there.

Enough that you made your money back?

I made my money back. I didn't lose my shirt.

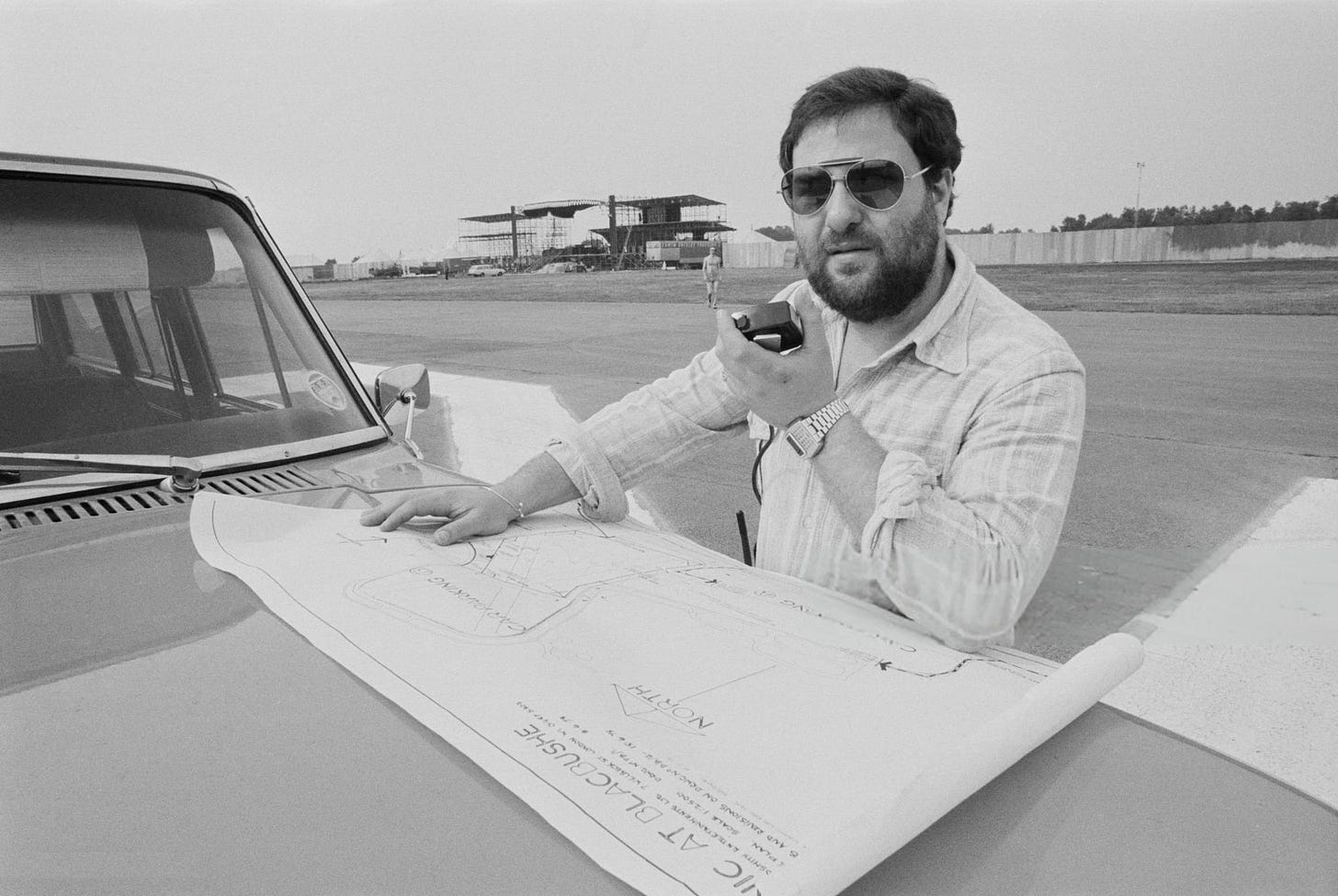

What was the planning of that event like?

I did a lot of shows in a theater called the Rainbow Theatre. One of the guys that owned the Rainbow Theatre liked planes. He phoned me up one day, he said, “I've got a great site for you. Come out and have a look” I'd never heard of Blackbushe Aerodrome, to be honest with you.

I went out to have a look and I met the owner of it, who was a collector of old planes. I thought, “This looks great.” It's flat, you could contain it, and so on. So I said, “Okay, let's do it.” I just had this feeling that Dylan was riding so high that, if I put a good bill together, it would really work.

Moving into 1984, how did you get involved in the two UK shows in Newcastle and Wembley?

His management called up and said, “We want to come over. We've got this idea of working with Santana; we're going to do quite a big tour of it.” They wanted to go big. So I said, “OK, let's play with the stadiums.”

The ticket prices were 11 pounds, which is about $14, and the booking fee was 50p. Strangely enough, we sold about 40,000 tickets, and then they stopped selling. I couldn't figure out what the hell was going on. I phoned all the box offices up and said, “Are you still holding tickets?” Because that was the days when we were physically distributing tickets. And they said, “Yeah. People are coming in, they're asking, ‘Is the show still on? Are there tickets left?’ and then ‘Ok, we'll come back another time.’”

So I had this brainwave. We had about 20 box offices scattered about selling tickets. I went to all of them and I left them with only about four or six tickets each. I said, “I need them because other box offices are sold out.” I told everybody the same story. The strangest thing is, within about four days, the whole lot went and we were sold out.

The scarcity factor. People thought everyone else is going to be there…

Yeah.

I was talking to Thomas Johansson in Sweden, and he was saying that there was a promoters field trip to Verona to see a few of the tour’s early shows. What do you remember about that excursion?

It was good fun. We all knew each other because, when the Beatles split up and Paul McCartney put Wings together, we formed a group of promoters to go and to do the Wings tour. We set up this kind of circuit. Then we bought the Beach Boys, Peter Frampton, Joe Cocker and Mad Dogs & Englishmen, all the Wings tours. A lot of shows.

It's no different from what AEG or Live Nation do today: Go out and buy the act for a number of cities. We weren't together as one, we were all independent, but we set up a circuit. We'd always work together on it. Strangely enough, we were doing so well with it that we got stopped by the monopolist commission who said we were creating a monopoly. But while it lasted, it was good.

What do you remember about the specific shows at St. James Park and at Wembley with Santana?

At first I wasn't quite sure about it, because it was a bit of an odd mixture. I liked Santana a lot, but he and Dylan were kind of two ends of the spectrum. Somehow or other it seemed to work. Then in Newcastle, we had Lindisfarne on, who were huge at the time, and we had Nick Lowe and UB40 on at Wembley.

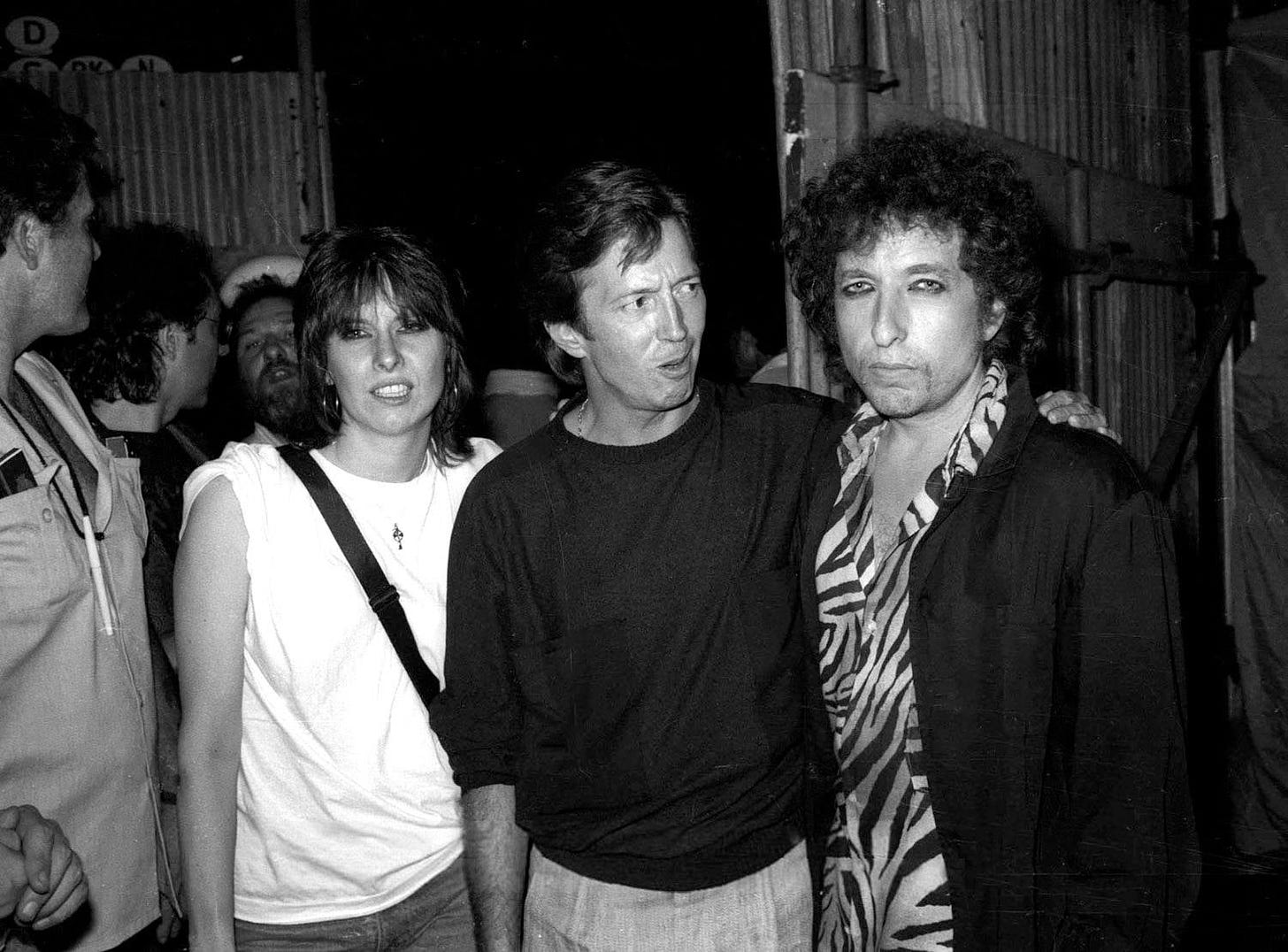

Then of course the surprises started to come out in the encores, Chrissie Hynde and Eric Clapton and Van Morrison. That really knocked everybody flying.

Did you know in advance that those three were going to join, or was it spur of the moment?

I knew they were going to come and play, but we decided not to announce it and keep it as a surprise.

Can you tell me about those two venues specifically? Wembley is super famous. I'm not really familiar with St. James Park. What were the spaces like to see concerts?

St. James's Park is a football club, Newcastle's home ground. It's about 44,000 capacity, something like that. It was used very rarely for concerts. I did Bruce Springsteen there, I did the Stones there, and this. So not too many. It started being used again recently, but there was quite a long period of time when it wasn't used. Because they were reseeding the grass at the end of the [football] season before the next season, there was always a short window to put show on. So if you fitted in with that window, great. But if you were outside it and they were reseeding the pitch, then you couldn't do anything. And so we just happened to fit at that point in time.

None of these stadium had held a lot of concerts because they were all sports stadiums. With a stadium, they're all hard work. You just got to knuckle down make sure that everything's in the best circumstances for them to perform as best they can.

And then Slane Castle came after. Jim Aiken, a well-known Irish promoter, did that show. I helped. The people that owned Slane, they wanted to be part of this mix. I'd actually been there to meet the Earl of Slane or whatever his name was. They were huge fans of Dylan, and that's how they got it. Bill Graham called and asked me all about the place. I said, “It’s a great space and I think they'll do a great job.” It was like the second coming in Ireland because he hadn't played there much at all.

Do you remember any particular offstage interactions with Bob or Carlos?

With Bob, I knew my place, put it that way.

When we did the Earl’s Court shows [in 1978], there were people every night coming backstage, and he was quite bemused by it all, particularly with Princess Margaret and the Aga Khan. He was intrigued. When he was doing that tour with Santana, he was becoming a bit more aloof and wanted his privacy. As with most artists, you can sense it when when he wants to be quiet and on his own and not be driven mad. Then you just keep out of the way.

It wasn't in a bad way. Nothing difficult. But I could just sense that this was a slightly different kind of thing. When Eric Clapton and Van came and all the rest, at that point he was much more open. But earlier in the day, during soundcheck or whatever, we just let him get on with it.

One year later, you did Live Aid, this giant triumph with the weird little asterisk of Bob Dylan's performance, which is a lot less legendary. Do you remember anything about that? You were probably at the London one. [The concert took place on multiple global stages; Dylan performed at the U.S. stage in Philadelphia]

I was at Wembley, but I was on the phone to Philadelphia every 15 minutes making sure everything was going alright. Half my staff, they went out to run the Philadelphia show with Larry Magid.

I'm not sure how [Bob] took it on that show, but it clearly was a different vibe. He and Bill I'm not sure were getting on that well at that point. Bill went a bit crazy over that show, and Larry Magid ended up really doing all the work with my team. I just sent half my team over there to put it all together.

Some people often hold up Live Aid as one of his worst performances ever.

Well, it wasn't brilliant. You know, Dylan is not one of these people that does 15 minutes very well. But that's how it went. I mean, we were just trying to get the show going. It all came together very quickly.

I could do everything except perform on stage. You could just give them the vehicle to do it. It's up to them whether they want to take advantage of it. Queen and U2 and Madonna, they took advantage of that situation. Led Zeppelin, when they came together, they didn't enjoy it. The Who came together; they didn't enjoy it. Just the way it was.

You'd think that doing it for a good cause would get everyone on their best behavior, but I guess people don't work that way.

It's not behavior. There's a thousand and one things that can spook you. When you're really rushing on, and you’ve not played four or five numbers—before you really get into it, smell the audience, feel the audience, etc, it’s all over. It's just how those shows work. Some people can grab ‘em. Some can’t.

Moving forward again a few years, you're involved in the 30th anniversary. What was your involvement there?

Bob called me up and said, “We’re doing this show. Ron Delsener, the New York promoter, is supposed to be dealing with it, but it's not coming together. Can you put this together?” So we went over to New York and we helped put this whole show together.

What do you mean put it together?

A lot of the acts had kind of agreed, but there was no shape to the show. There was no design. Part of the magic of a lot of these shows is who goes on when and how the flow works, and that hadn't been done. And organizing the rehearsals, trying to get people to play together, and all that. It’s more than a concert, because with a concert, the artist is in complete control. But when you've got multiple artists, it's the producer who's really in control. So Bob asked me to produce that show, which is what I did.

Are the artists picking their own songs, or are you assigning? Or Bob?

They would suggest something, [or] Bob would turn around and say, “I think you should do this.” On the actual musical side, I kind of keep out of that. My role is to really decide how the running order should work so it flows smoothly. They pretty well work out what they're playing together.

When the show's going on and you're sitting there and something like the Sinead O'Connor thing happens, are you tearing out your hair out?

We didn't have time to tear our hair out. We just had to deal with it.

She was in a terrible state. She came off stage and I had to sit down quietly with her, try and calm her down—and then, at the same time, make sure the show carried on. It was a very strange and weird situation, but they happen in these kind of shows.

On the happier side, do you remember any of those artists that you were particular favorites that you enjoyed working with on that lineup?

Well, you know, obviously Tom Petty was great. Eric [Clapton]. I mean, all the normal guys. Again, they wanted to do those shows. If you don't want to do it, it's never going to work if you're pushed into it. But I think everybody wanted to outshine everybody else. Which is great because that's what makes it really fly.

How did you end up getting that Bobfest guitar signed by all of them?

At Live Aid, we asked everybody to sign six posters and two guitars. We did the same for [Bobfest] because we just thought it was the right thing to do. Everybody did. So I got a memento.

One other show I wanted to ask you about is another giant one, the '96 Prince’s Trust in Hyde Park. Another one of the biggest Dylan shows in the UK, I believe.

I was asked to put together these Prince’s Trust rock concerts and this open-air show was the kind of culmination of a run of indoor shows that we did.

I think Dylan in that period of time was kind of in a different space. He played, he did the right thing or whatever, but the vibe wasn't quite the same, put it that way. [laughs] I'm not sure that it was my choice for Dylan to play on that show, to be honest.

Hyde Park's not an easy place to play. We played at the top end of the park, not where it is now. The sound is always a bit difficult because you get crosswind. The wind goes across where the stage is, so you get this wafting of sound. There's nothing you can do about it. It's not my favorite place to do shows. It was one of those…we got through it.

Were there other Dylan shows you worked on?

No. Dylan changed management and he started working with Jeff Kramer. Jeff Kramer, for whatever reason, always worked with another promoter. But funnily enough, I've stayed friendly with Dylan. I haven't seen him for a while, but there was a period of time where, if he was playing New York, I'd go and see him. If he came to London, I'd go and see him.

I remember one night when he played at Wembley Arena and he had this really awful band. He'd kind of play with his back to the audience. My wife and I went to see the show and I thought it was awful. We left before the end.

I got home and I was in bed just about falling off to sleep. The phone rang and it's his security guy. I gave him a security guy called Jim Callahan, and they fell in love with each other. Jim was by Dylan's side wherever he went.

Jim called me up about half past one in the morning. He said, “Where are you?” I said, “I’m in bed. Where do you think I am?” He said, “Bob wants to see you.” I said, “Okay, well, I'll see him in the morning.” “No. He wants to see you now.”

I said, “Are you kidding?” “No, he's in the Mayfair Hotel in the West End.” That's like 50 minutes away from where I live.

So I got dressed, drove up to the Mayfair Hotel. My wife thought I was fucking mad. It's now about two in the morning. Dylan was sitting in the corner of the bar. The bar was shut. All the lights were off except one dim light over where he was sitting.

He said, “I saw you leave.”

I said, “Don't be daft. There are 11,000 people there.” He said, “I saw you and your wife get up and leave before the end. Didn't you like the show?” I said, “Well, actually, now you've got me up and it's half past two in the morning—I hated it!”

He looked at me. He was sitting in the corner, and he looked at me and said, “How much does Eric Clapton pay his musicians?” I said, “Clearly a damn sight more than you do.”

We had this bizarre conversation. It went on for about an hour. Then I said, “Bob, you've got to go to bed and I've got to go to bed.” It was just a funny, funny conversation.

Do you think he actually saw you leave early?

He must have done, because how else would he have known? No one else knew. How weird is that?

Then I saw him in New York. We had a funny talk when he was doing a show at the Garden with Eric Clapton and a few other people. I came backstage just to say hello. I knocked on the door. He opened the door and looked around. He said, “Come in, come in.” I went in, and he shut the door and locked it. He said, “We have to talk very quietly. I don’t want anybody to know I’m here.”

So we’re talking away, and then his manager came. He knocked on the door, said, “Bob, are you there?” Bob said, “Don't answer!” He started pounding the door going, “Bob, where are you? Are you there? Answer the door!” I said, “For God's sake, you better let him in, otherwise you'll kill me.” He said, “Go and hide in the toilet.”

Really?

Really! It was hysterical.

He has a very mischievous side to his life, to his persona. As well as being difficult, he's very funny. And I love him for it, because he's in a class of his own.

Thanks Harvey! One more big piece of new 1984 content coming in a few days. Until then, recordings of the shows he promoted, plus one of the opening sets (if anyone has the others, let me know!):

1984-07-05, St James Park, Newcastle, UK

1984-07-05, St James Park, Newcastle, UK [Lindisfarne set]

1984-07-07, Wembley Stadium, London, England

ICYMI, catch up on the two previous interviews in this series:

The Men Who Put Bob Dylan and Santana in Stadiums

This summer marks the 40th anniversary of Bob Dylan’s enormous summer 1984 European tour with Santana, which became the album Real Live. To celebrate, I’ve got a number of different ‘84-themed posts coming. Three of them are new interviews with the people who worked behind-the-scenes to put on these giant sh…

"I still adore Bob Dylan. But don't tell Joan."

Today, the second in my series of interviews with three of the promoters who helped put on Bob Dylan’s giant Real Live stadium tour in 1984 with Santana and, at some shows including today’s, Joan Baez. (If you missed the first installment, it’s here).

Great interview, Ray. I wonder if you know what show he walked out of?

Ray~

You continue to amaze on your journey following the musical footsteps of Bob. Your work is inspiring and thrilling.

Thank you,

Miles

Chicago