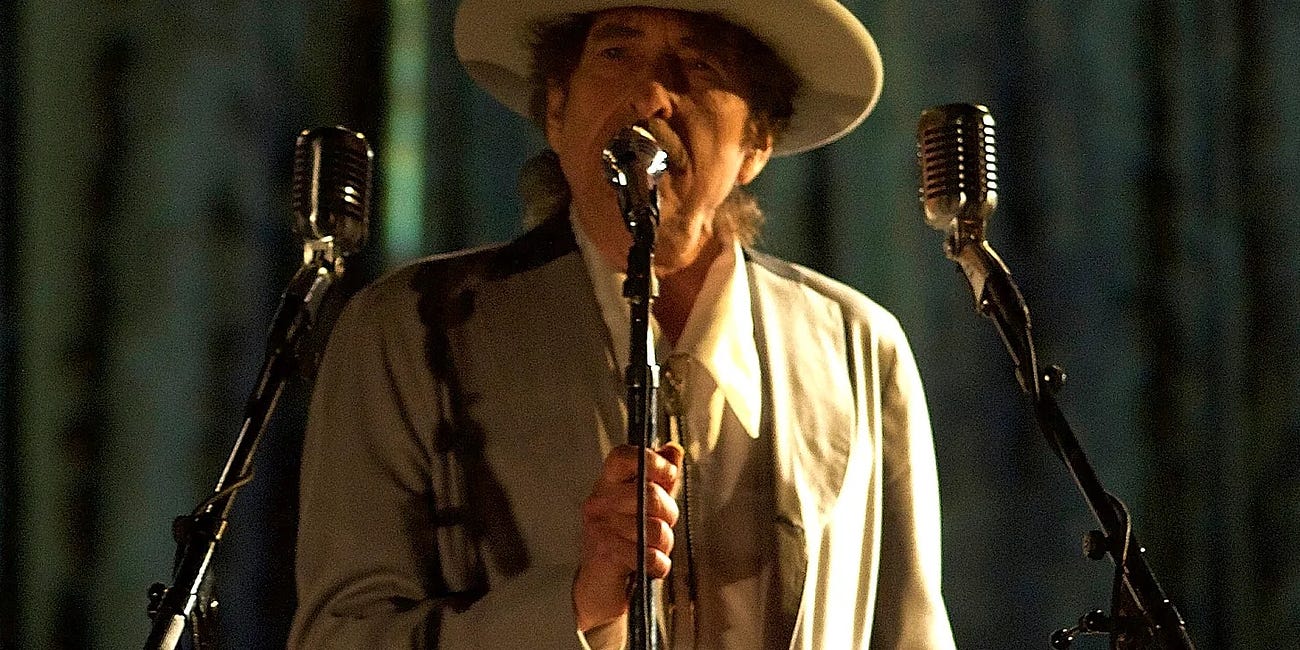

Guitarist JJ Holiday Talks Bob Dylan's Iconic Letterman Performance 40 Years Ago Today

Plus the months of jamming that led up to their three songs together on national TV

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

Forty years ago today, Bob Dylan gave one of the most unique performances of his career. He appeared on David Letterman’s buzzy new show with a band several generations younger than him, playing raw and energetic versions of two Infidels songs and one blues cover. “Bob Dylan goes punk” is the shorthand fans use, though one of those “punks” takes issue with that description.

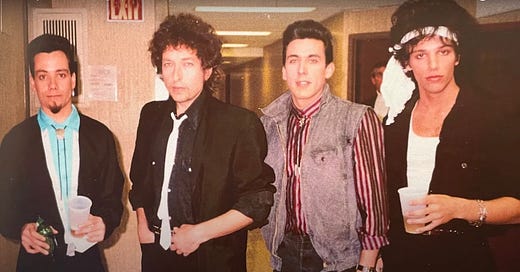

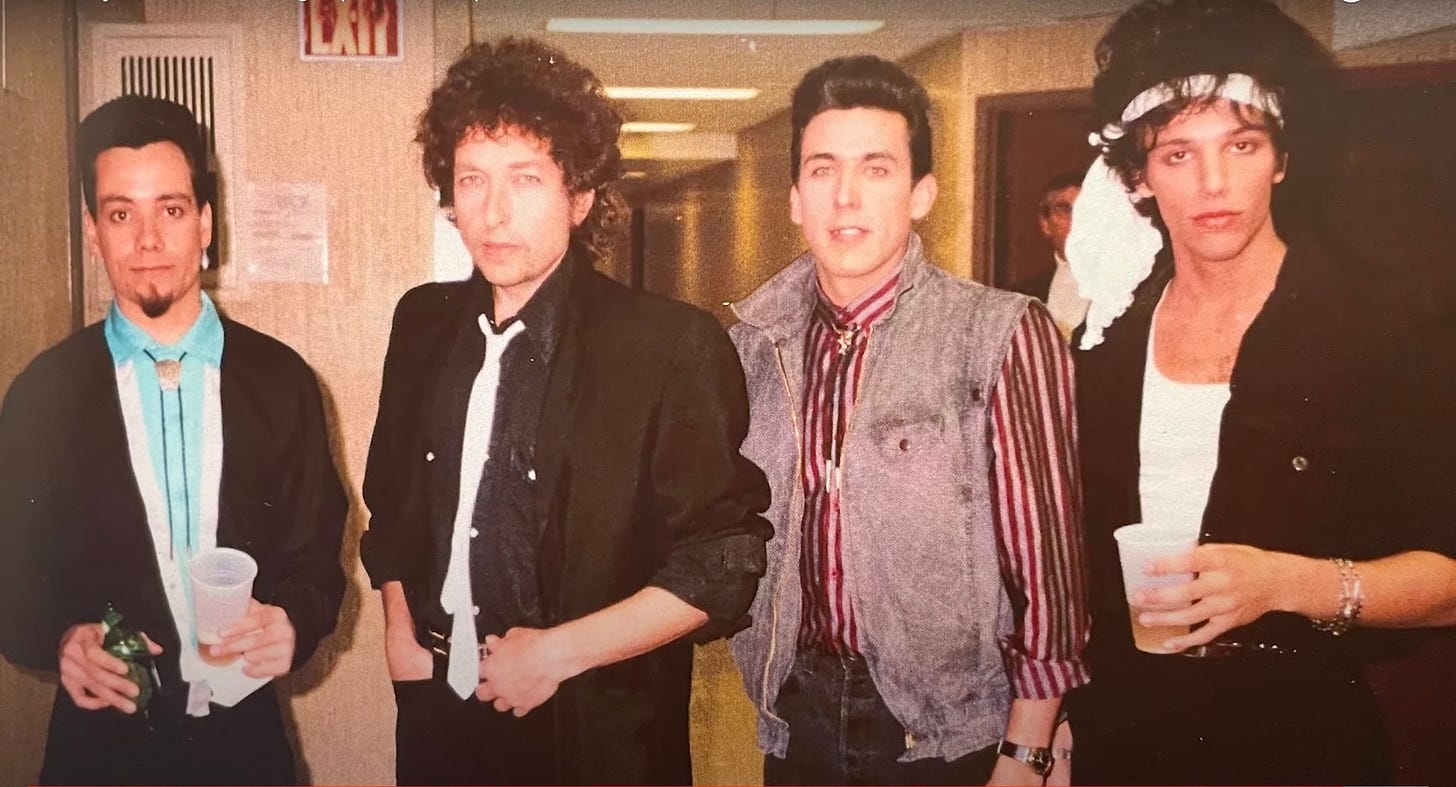

I recently spoke with JJ Holiday, guitarist for the band that day alongside two members of LA group The Plugz, Tony Marsico on bass and Charlie Quintana on drums (again complicating some oft-used shorthand, “Bob Dylan and The Plugz,” Holiday was never actually in The Plugz). Despite months of on-and-off jamming at Dylan’s Malibu house and vague talk of tours that never came about, they only ever played those three songs together in public. Holiday was just 25 years old.

Last year I spoke to bassist Marsico about the experience. I tried to cover different things with Holiday rather than re-tread the same turf, so after you read this go back and read Marsico’s interview if you haven’t already. That entry also has snippets from a set of rehearsal tapes made at Dylan’s place, which Holiday referenced in our conversation. Here’s me and JJ Holiday…

Let's go back to 1984. Can you run me through the story of how you got involved with Dylan in the first place?

Well, it is 1983 when that started. Charlie [Quintana] was the kingpin for all this. His girlfriend, Vanilla Neulan, worked for a guy named Gary Shafner, who was Dylan's guy. At one point, they were like, “Hey, Bob Dylan is looking for some younger guys to see what's going on out there on the street.” She said, "My boyfriend plays drums; he could do it." Charlie was a real smooth operator, a great guy, and a solid drummer. I miss him. He became the connection there and just started bringing different people up to Bob’s place. Bob would check them out; people would come and go.

It was a very small setup. Very informal, very casual, very relaxed. Bob was nicer than pie to me the whole time. Listening back to those [rehearsal] tapes, I see, he was very giving, very forgiving. He was inventing on the spot.

What do you remember about your impressions when you first arrived?

You don't know what to expect. Charlie said, “Oh, we're just going to go up and jam,” which is exactly what we did. When I first walked in, I think I had a guitar in my hand. I don't even know if I had a case. You have to realize how street-level we were; I didn't always have cases for guitars. If I needed a new guitar, I'd have to trade one. I'm not a great trader. I always ended up trading down.

But I walked in, and he was right there. I think, "Oh, that's him. Whoa. Okay." He puts out his hand and we get the handshake you've heard about many times.

The dead fish.

I'm sure after 50 million handshakes, you don't want to do that anymore. It hurts your hand.

Then we just got into it and started jamming. A lot of that guitar you hear [on the tapes] is him, not me. If you hear slide guitar once in a while, that's me. Other than that, we were about equal volume. It was just back and forth. He's banging out chords the way he wants to reinvent whatever song we were doing. It seemed like he had nothing in mind other than the moment. He was very free that way, which was great because we were used to that.

I’d collected 78s since I was about 13 or 14. You eventually work your way back and become a bit of a scholar. You read the back of album covers. Like a Dylan record has Sleepy John Estes on the back. I remember reading that name as a kid thinking, "Who the fuck is Sleepy John Estes?" You look at the Stones records and they talk about Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf. Beatles, Led Zeppelin records, same deal. You work your way back in time, the road narrows a bit, and you find out about those first recordings: Charley Patton, or Blind Willie McTell, Blind Willie Johnson, or Blind Blake, a big hero of mine. Now, you’re hooked.

The shorthand for this Letterman thing is always “Bob Dylan meets the punks,” but it sounds like you were more steeped in the blues.

No, I was never particularly a “punk music” fan per se. I couldn't tell you one band from the other really. Though I love garage-type bands still, and I was a total punk in my attitude, that music genre sort of missed me. I just heard much of it as a bunch of bashing around. Shame on me maybe, but I was deeply focused into that other thing. Back then I'm listening to guys like Leo Kottke or Stefan Grossman or Scotty Moore or Mississippi John Hurt. Rockabilly and old blues. And then trying my best to incorporate their different sounds into my own weird and developing guitar style.

I had a good musical upbringing. My dad was an old ‘50s greaser type of guy, always had a car engine broken apart in the garage. Much of my family were stock car people and crew. My uncle was quite a well-known West Coast driver named Jimmy Insolo. Via that vibe, my dad had Bo Diddley and Hank Williams and Johnny Cash records. Cash was the king at our house. I remember my dad had a Joe Maphis record. This guy had a double-neck guitar and he played the hell out of the guitar. I grew up with that stuff blasting on the Hi-Fi and the cars revving up.

I'm sure it's not lost on you that a lot of the people you're naming are also Bob Dylan's early influences.

That's what I'm saying. I think he saw that right away. I probably just started playing a little fingerpicking. I really like fingerpicking. I play guitar equally in standard tuning and open tunings, generally G or D. With a slide on or off my ring finger, either way. He knew all that stuff, and he definitely connected with me there because I could even mention a name. I said once, "So this is like a Buddy Boy Hawkins thing or something?" and he just goes, "Yeah."

I have a few so-called parlor guitars. They're small bodied, like you might have sitting in the Victorian living room. In the ‘20s, a lot of blues players played them. You could buy them from Sears. I brought one in, probably like a 1910 Washburn, and I played it a little bit. One particular time, I remember setting it down while we took a break. Bob comes and looks at the guitar. He says, “Man, that looks like a guitar Abraham Lincoln woulda played!” I just remember laughing. So did he. What a comment. I mean, that’s the kind of vibe that we all had going.

From what Tony was telling me, you were not the first guitarist tried. There had been previous people who had been rejected. I wonder if you having that background, as opposed to people who really were part of the punk scene, gave you the edge.

Could be, yes, that's got to be it. When I listen to those tapes, he's very kind and he's showing me stuff on the guitar. He wanted to play in open G a lot. In fact, all those songs we play on the show, I'm tuned to open G. So is he, I believe.

The guitar I played on the show was a Telecaster, not set up for slide, unfortunately. To this day I think, goddammit. But you can only bring so many guitars on a plane. When you start playing in open tunings and slide guitar-- like Ry Cooder, he might have to haul around how many guitars?

Is open G the Keith Richards tuning?

That's right. Bob obviously saw that right away. I probably brought up a guitar or two and had one tuned that way. I think he tuned right into that. I hardly know anybody that plays like this primarily. Nobody that I knew of in that punk world did that.

The way those songs developed; we didn't always know what song we were playing. We were just jamming. I’ve often read the word “rehearsal,” or that we “rehearsed” a lot. Well, we didn't “rehearse” really at all! We jammed. It was like, “Well, I guess we are working on that song now…” Later we might learn it turns out to be “Jokerman” or something called “Destiny.”

“Destiny”?

I have a distinct memory of asking one day, after jamming on a particular groove for a while, what it was called. He quietly said “Destiny.” That music may or may not have been recorded on any of the boombox tapes. At this point, I frankly don’t recall how it sounded. Just a title, “Destiny.” I like it. Nice mystery. It stuck with me somehow.

I'm glad I didn't really know the originals at first, because he often played them differently, which seems to be typical, as I’ve now gathered. Because of that, it's loose and fun. We would start playing something in one key and get it down and then he might switch to another key, probably what suited his voice a little better. I remember rehearsing at Malibu one time, and he stops. He's just checking out the vibe while we're playing and he says, "Man, I think if I called Keltner, he would get a real kick out of this." Obviously, something Bob heard was hitting him.

There were never any microphones or PA in that jamming room other than the boombox of Tony’s that was sitting there. That's why you don't hear him singing out very well, whenever he did, which was rare. Bob himself tried recording some stuff early on, just trying to catch grooves and stuff that we might hit on. He had a reel-to-reel sitting there originally. I don't think he set it up right; I remember the tapes were just flying around. He runs over to this reel-to-reel thing and shuts it off. Well, as soon as he stops playing, we stop playing. He goes, "No, no. Keep it going." He starts laughing. We didn't know, oh, we got to keep this groove going.

Tony had that boombox that it was placed over by Bob's guitar. Same setup on the stage that you saw on the show. I never listened to those tapes at the time. I just wrote my little notes and that was it.

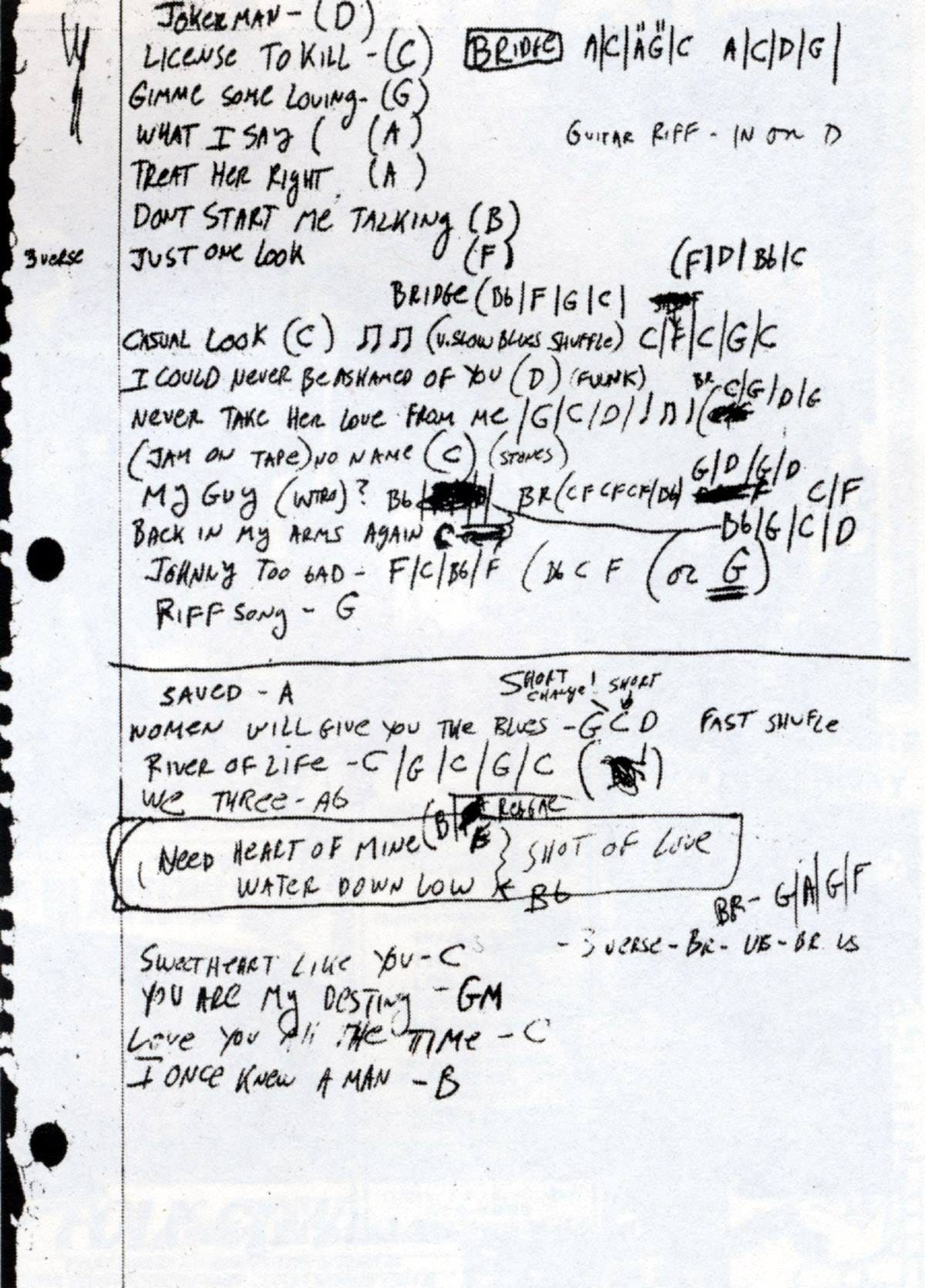

What were you writing for your little notes?

Just a title that I could maybe catch or a feel. Like we jam for a while and I don't know what it is, and he's singing maybe a little bit to himself. He sang out more if Clydie King was there. Boy, did she sound good. When somebody sings like that and can fill a room, it's godly. Really great harmonizing. You hear that on some of those tapes.

Was there ever any talk of Clydie being part of the Letterman thing, or being part of anything other than just jamming at Bob's place?

When the idea of playing live came up, I asked him. I was definitely thinking there'd be like a keyboard player there and singers. And he said, "No, it’ll just be us doing it." I suppose if we had done a tour or something, maybe she would have been on that. They were hanging out a lot. That would have been great.

In the tour he did in the summer, he did add a keyboardist [Ian McLagan]. Not any backing singers.

Is that right? Well, only the best there. I would think he'd have some kind of keyboard in there, or something to fill out the sound a little bit. It's kind of essential to a lot of his music. But he just wanted this stripped-down deal like we did.

You said you would just write down song titles or something. Would you then take that home and go find the record it was on?

There were a couple times he wanted us to do that. I think from Shot of Love, he wanted us to learn “Heart of Mine.” He told us that there are versions of it that Gary had, that he wanted to do more than the way it came out on the record.

Gary would dub tapes for you of the correct versions?

That was the idea. I don't know if it ever really happened.

I remember Bob referring to Shot of Love. He didn't understand why it didn't sell. He said that once to us. He said it's a good record but it just didn't go anywhere.

He said funny little things on the side like that. I remember we were talking about getting together at some point in the future, working around schedules. He had a lot of obligations, but he wanted to get together. He did say once, "I have five record contracts” or something like that. It seemed to me he was a little burdened by it, the things that he had to do. Like maybe he would rather have just gotten together and jammed the next day instead of waiting a week or two. That was my impression.

I watched a lot. I observed a lot. I absorbed a lot. He really allows himself to tune in to whatever's going on in the room. You start playing and let the mood of the moment guide you. You might not have an idea of the song you want to do, but just start banging on the guitar and you'll find it. That's kind of his method. I think the guy operates very freely and he was just having fun the whole time. I do understand that at this later age.

What do you think of him as an electric guitar player?

He was good in the rehearsals. When he starts to solo, maybe it's not really his thing, but maybe he's also searching for a melody or something too. It varied. You had to pay attention. I would say Bob’s an acoustic guitar player first, but it's hard to do that with an electrified band. You're not going to play ragtime guitar on your amplified Strat. It just doesn't really work.

How many instructions is he giving you? Is he giving you tips, play it like this, or anything like that?

He seemed to have a way he wanted things to go but he was also searching for it at the same time. Both at once. You just knew to listen to him. He's the boss. We’re just there as instruments, really. I know that a million other guitar players could have filled my shoes. Much more accomplished guitar players for sure. How many musicians has Dylan played with? A thousand?

You just knew that he's going to work it out and when it seems to be going somewhere, catch it and emulate it. I wouldn't say instructions per se, so much as, here's the guidepost. He would tell you if it didn't work. If it was working, he would often say nothing, he would just keep going.

Tony talked about how Bob loved your coffee. I wanted to ask what was special about the JJ Holiday coffee in 1984?

I don't know. [laughs] I mean, I like strong coffee. In Malibu, it could be a little crisp and overcast where it's sunny out in the Valley. Charlie and I would get there in my Volkswagen. I would say the general time was early afternoon. Bob was rarely there yet. So we'd make coffee and sit around and tune our stuff up, then he'd come in. You often wouldn't even notice him coming in. All of a sudden he was just there.

One time I was making coffee. It was like hippie-style coffee. Just pour it into the top of each cup with the filter holder. It's steaming away, looks really good. Just over my shoulder comes, [Dylan voice] "What's that?" "It's coffee. You want some?" "Yeah!" From then on, that was a little thing.

Do you remember any other specific things Dylan said to you during those rehearsals or whatever we're calling them?

He talked about The Clash, who we knew. I'd seen them live in about '79 or so. He liked them.

He was asking you guys what you thought, as the people who were maybe more in The Clash’s demographic?

Exactly. He brought them up at some rehearsal one day. It was a band he knew about and thought well of. You're talking about a straight-ahead rock and roll band at the time that had made it in a big way.

Tell me about this idea of going on tour in South America. Obviously it never went anywhere.

It was floated around. After jamming there a couple times, we hear that maybe we're going to play out somewhere. There was one time that we're going to go to play at a CBS convention, I think in Hawaii. I was like, “Let’s go!” That didn't happen. Then at one point he wanted to do a South American tour. It was going to be an incognito tour. Different. I remember him saying specifically, "It's not going to be a ‘Bob Dylan’ tour." He used those words. “Bob Dylan” being an entity, you know, even beyond him.

“Bob Dylan” the brand.

That's probably what he was getting at. Or maybe just a lower profile thing. I think he was doing his best to try to make something like that happen. But it just didn't. I remember at the time thinking, "Oh, shoot, he told us we were going. Goddammit.” Knowing much more now these days, as a much older person, I absolutely get it. It just doesn't work sometimes. But I know he tried. We would probably have played theaters and clubs and who knows what, just under whatever name he wanted to call it. That would've been great. That would've been really great.

One thing I want to say: I've always thought our second gig would've been stellar. That's how I think about the whole thing. Our only public appearance, was very raw, and maybe kind of cool because of that? We just started working out all the usual kinks right there on national television. I mean, who does that? You’ve got to hand it to him for being that bold.

On that tour he did in 1984, the Real Live tour, I saw an interview with Martha Quinn. A cute host that was one of the early big hosts on MTV. She was interviewing Bob Dylan backstage on the Real Live tour. You could see he was charmed by her, and she was sweet and asking quite thoughtful questions. At one point, and this is the only reference I've ever seen to anything we might have done, he says, "You know, this isn't the tour I wanted to do. I wanted to do a different tour." I'm thinking, "Oh, is he talking about the South American tour?"

I've read things like, "Oh, he should have played Real Live with those punks." There's no fucking way we could have played that. We weren't ready for the stadiums. I surely wasn’t, anyway. But we would've played great in the smaller South American clubs, and gotten our shit together after a few gigs.

At a certain point, are you getting frustrated that you're spending months on and off jamming for no obvious purpose?

No, never frustrated. It was sublime. It was always great. I had a job; I played a lot of gigs. In those days, you could play in a lot of different bands and just be a guitar player and make a few bucks and pay your rent. Rent was a few hundred bucks.

Were you getting paid for all those jam sessions? Was there a retainer or something?

We were getting paid. No such thing as a retainer. These sessions were pretty random. Just day by day. We’d get a check in the mail later. I think we were getting $90 or a $100 each time. I was thrilled.

I had a job as a cocktail waiter at a hoity-toity restaurant. You're in Hollywood, so it was that kind of place where people like Rock Hudson came in and Tony Perkins and guys like that. Older Hollywood. I remember having to call work when we'd get a call about going up to Malibu. They got pissed at me. I lost my job. I remember I was like, "Fuck that. Who cares?"

Were there separate rehearsals once the Letterman thing does get decided on? Did that change what you all were doing?

A little bit. I think it was probably getting more focused, unbeknownst to us. Like I could tell we were going to play “Jokerman” for sure. We knew that, just not if it would be first or second or third. We played “Jokerman” a lot. Well, anybody with any perception could think, "Oh, okay, so this is what he wants us to play." He'd never say it.

You could read the tea leaves.

You needed to.

Take me through the day at Letterman. What happens when you first show up?

Well, we were staying at a fancy-dancy hotel. Not what I’m used to. Duran Duran was staying there too, and there was a crowd of fans around the place. I just remember pulling up and saying, “Well they’re certainly not here for us.” The road manager taking care of Duran Duran's business was right in front of me when I checked out. Their bill was something like $15,000.

We go to 30 Rock. We all wanted to meet this guy named Larry "Bud" Melman. I think I've read that even Bob did. He was a character on the Letterman show. He sort of personified a certain New York old-timer attitude. When he brought that up, "Hey, you think we should do this? There's a Letterman show." Of course, we went, "Yes, now. Let's go." He got the idea it was a cool show to do.

Did you meet Larry “Bud” Melman?

I met him. I didn't talk to him much. I just remember meeting him and thinking, "Wow."

When we got there, the stuff was set up, we just started playing, and a lot of that's on YouTube. The room was abuzz; a bit of a crowd gathered. He's just going through songs that were on our list, but never completed. I don't think we ever did a straight beginning or ending on anything. He did emphasize some songs, but we still didn't know what songs we were going to play exactly. I think Bob was going to play it by ear.

During rehearsal, I remember him gathering us all together after a couple of songs. They're blocking the show, getting the monitors set up, and I remember him getting us in a little huddle and saying, “This is what I don't want. I don't want them to just show my face. Don't just shoot a close-up of me.”

You know, because they tend to do that. You don't get to see the musicians in the band; they focus on the forehead of the singer. And it's not really representative of a stage or show. You see this on documentaries and stuff all the time. They'll zoom in on Joe Cocker's sweaty brow, and the band's bringing it back there but you can’t see them.

He was telling you this in the huddle?

He was sharing that with us. I think at some point he walked over to Gary or somebody like that to let them know. Because look what he did. He walked outside the monitors [during “Jokerman”]. He was making a point to not be by the book on the show. So they showed a lot of the band, which is unusual.

In a way that's what makes it so cool. Not that watching Bob Dylan alone isn't great, but one reason it's famous is because of the combination of him and you guys, both how you sound and how you look.

I do remember not knowing what we're going to do. We're a little nervous about that. Charlie, a real rascal, got me to go over there and ask Bob. You know, “Why don't you go ask him JJ?” Like that commercial, “Hey Mikey, try this…” I remember Bob not being worried at all. I said, “Um, we're just kind of wondering what you're starting with.” He just said, “Don't worry about it.” And I remember this term, he said, “Just go out there and look cute and punky.” It was very nonchalant; there was no heaviness to it. Those were his words: “cute and punky.”

That coat and skinny tie Dylan wore on the show was actually what Charlie brought in for himself to wear. Bob liked the outfit and asked Charlie if he could wear it. They worked it out. Charlie ended up wearing his regular street clothes, looking great nonetheless.

His son Jesse was there. Bill Graham was there. He advised us to just watch Bob close and stay in touch with one another while playing. Sage advice, always. We met Liberace, which was the craziest thing. We met “Bud” Melman, and the house drummer, Steve Jordan.

Do you know why Bill Graham was there?

In that little clip with Martha Quinn, Bob mentions Bill Graham as one of the only guys that could have put [the South American tour] together. A South American tour in the ‘80s, the logistics behind that have to be a little weird. You're talking a scary kind of time. Especially to go there without a big production behind you, like I think he intended.

“Don't Start Me Talkin’,” the first song you actually played on the show, seems like an odder choice than the other two.

I know, right? That's pretty bold. The day of the show, the three of us are talking in our little green room. "What's he going to play?" "I don't know." We got word, I think, eventually we're going to do “Don't Start Me Talkin'” and it's in B. For me, that meant a capo because I was playing in these open tunings. I ask him, "Are there going to be solos? The stops [on the original recording], do you ever wanna do those?” He goes, "If it's going good, I'll keep it rolling. If it's not, I'll signal and we'll just cut it off.” It was very loose that way. There was no specific arrangement.

We were all familiar with just winging it. Our whole life was winging it. How are you going to make rent this month? How are you going to get over there with no gas? I think something unusual about Bob Dylan is he seems to want to keep it alive that way. It's an art in itself.

You can over-rehearse, and then you're starting to worry about doing things wrong, you're starting to worry about making mistakes, because there's only one way to do it. That's no way to play on stage. That doesn't give the energy that you're supposed to give as a performer. There's guys that play the same guitar solo every night and it's great, but wow, every fucking night? The joy is in, "Well, I got into this box. Let me get out of it."

I was rewatching the soundcheck earlier that day. It's five songs, three of which are different than the ones you actually played. You do “Jokerman” and “License to Kill,” so those are the same. Then you do “Treat Her Right” and “My Guy” covers, and “I Once Knew a Man.” I don't even know what that song is.

As I remember it, that just came out of a jam. He might have shouted a key and that it was going to be a blues. I'd come up with a little riff that works. Those kind of songs, they're very natural if you know the genre. There's certain formats that you use. It's AAB, but they vary. That one time might've been the most complete time we ever played it. We might've fucked around with it a little bit. That was a good one.

“License to Kill” was my favorite of the three performed for sure. I was so glad they picked that to be included on the Bootleg Series. Well, they wouldn't have done “Jokerman,” because it got messed up.

Why was “License to Kill” your favorite?

I just thought it was the most sincere and best take we did. He sang that really well. I could really tell he was into it, the way he was singing it. We're playing it sort of in a Dylan-esque kind of ballad-ish way, which was easy for me to do as the kind of guitar player I am. I feel lucky that out of three songs, one out of three gets released. That's not a bad track record, 33%.

You’re a guitar guy. What guitar are you both playing?

I'm playing my 1968 Telecaster there. I also had a Sunburst 1962 Strat in standard tuning. He was playing his old Strat that you’ve seen him play quite a bit. It would have been in Open G most likely. There was another guitar around in regular tuning, with the dark rosewood neck maybe? That was Ron Wood's, I do believe.

Up in Malibu, you'd see cases laying around with little pieces of tape on them that would just say "Ron Wood" or it would say "Clapton Strat." As a young guy, I'm just thinking, wow!

The way it felt to us—to me anyway—was, Bob Dylan was just the guy we played with up there. I knew he was a giant star of course, but we were dealing on such a non-star level it didn’t come into play at all. We weren't below him in that way; no question, he was the leader, but he also made it feel that he wasn't above us. I'm glad I didn't fully know or feel the magnitude of it all at that time. That’s all just my take here, as I am reflecting now. It was a big moment and a long time ago.

You know what I looked up? Letterman was March 22nd, 1984. I saw that Bringing It All Back Home was released on that day, March 22nd. It was a nice little twist to read. Because he was bringing it all back home in his own way again on that day, wasn't he? When was the last time he appeared publicly, before we played?

He had done the Christian tours through '81, and then he hadn't toured at all before '84.

So maybe it was a bit of a retro return for him, in a funny way. I diligently listened to these rehearsal recordings you sent me, by the way. We played “Saved; “Saved” would have been great. “Lost on a River,” where they're [Bob and Clydie] harmonizing together, gee whiz, man. [Singing] “Lost on the river, river of life.” Then there's these endless little clips of “Jokerman.” He was working out a new version. That's all that was happening there, and it didn't take that long.

This is only two tapes. I probably went up there, I don't know, it wasn't like zillions of times. Maybe 10, something like that. But that's a long time to spend with a guy like Dylan. You can learn a lot. We'd spend hours there once we were there. We would just play the whole time basically.

I'll give you two ideas that I came up with. There's a big international forest known as The Bob Dylan Forest. We three are but a toothpick in all that. We're just a lonely little twig somewhere in the middle of a maze of big trees. Or maybe we fell off already and we're on the ground now.

And/or I've looked at it like we did the “pilot show.” There was a Bob Dylan ‘80s show that was just blowing up. We three did the pilot with him. He changed some characters, and they all did thousands more episodes. He got what he wanted with us, and we got more than we ever could have imagined.

Just to round us out here chronologically, you play your three songs on Letterman. What happens as soon as you walk off stage?

Soon as we walk off, there was no worry. We had avoided a complete train wreck.

That harmonica thing came close.

Yeah, right? I have no idea what happened there. I wasn't even worried about it in the moment. I go, "Oh, well, he got the wrong harp." You ever been on a TV show? I've done enough of them now, where it's very quiet. It's deceiving how quiet and unimportant it feels. Meanwhile, you've got this little red light looking at you, and it's broadcasting to the world. We probably, in one show with only three songs, played to more people than he did on the following tour. Then because it's recorded, it gets analyzed to death, which irritated me sometimes. I remember thinking way back, "Oh we did shitty, that was shit, he hates us." [laughs] I was just greener.

You mean immediately after? When were you thinking that?

No, later. Tony and I, we didn't know if we did any good. There was no way to play it back in those days without a video machine, which I didn’t have. But when we walked off the show, we felt pretty darn good. We just unplug, walk off the stage, and then we meet up with Bob outside the green room. We take some pictures. There’s a lot of excitement. We huddle up with Bob and that’s where he says the famous, "I'll call you guys on Monday."

So he goes off, and then we just head out onto the street. I remember a classic New York scene, seeing two cars whizzing by, a taxi and a limousine. They're going in opposite directions, really close, and they just hook bumpers. The bumper tears off one of them. They both kind of stop for half a second. Nobody gets out, nobody does anything. They look back, and then they both just keep going forward.

Bob's gone. He's going to call us Monday. [laughs]

Were you disappointed that that Monday call never came?

Of course we were, at first. Again, put yourself in the much younger mindset, I was now 25 and I didn't have my job. What did I care, really, but I'm just saying. I was going through personal stuff and “Oh, shit we're not getting those calls.” Then, pretty soon, we just started joking about it. Like, "Hey Tony somebody called when I was outside. Did you get a call? I missed it." Or “My phone machine wasn't on. Shit, that was Bob!”

It's been a joke between us ever since. In fact, we still greet each other sometimes that way. I'll just say, “Tony, I got a call…” We laugh.

I didn't know Tony as well back then as I knew Charlie. We had played together in a band or two elsewhere. But Tony and I are very good friends now. I didn't play in the Plugz as is sometimes written. It says “Plugz, Plugz, Plugz.”

It's really two Plugz, and one you.

Yeah. And they were a great band too. As I recall, I did overdub some slide guitar on an album of theirs later. So I get it. I was just a guy out there playing guitar in different bands trying to pay his rent. Definitely was a punk in the more traditional sense and general life attitude. That whole punk vibe, I think that's an easy handle to grab onto. Press-wise, it makes sense. “Bob Dylan Goes Punk.” I don't know. I guess there was an influence there, but I don't think we sounded particularly "punk" that day. It was just music. But it makes a cool little headline.

I worked for Johnny Depp’s development company for some years. I've known him since the late '80s. When you have that kind of stardom Dylan or he has, a lot of random and weird stuff is said out there, and they just have no way to deny it. You don't even want to acknowledge it or give it any more energy. That just comes with the territory of fame. I can’t imagine what's been said about Bob Dylan that is just not true at all. He doesn't really talk about it. It's the best way to go, I do think.

Years later, with the Blues Brothers, you opened for Dylan right? Vegas in ’99.

Our band is officially called The Sacred Hearts. It’s “The Blues Brothers with the Sacred Hearts.” We're not technically The Blues Brothers band because it's a business thing. Steve Cropper, a hero of mine, and co. are the real original Blues Brothers. We started in 1994. We opened many of those House of Blues venues. That gig was a new House of Blues opening in Las Vegas.

What was it like opening for Dylan many years later after you played with Dylan?

I didn't see him or talk to him. I talked to his guitar guy at the time. The guy noticed I had a couple of odd guitars, maybe it was an old 1961 Oahu guitar I still use, and he said something to me about it. I never got to speak to Dylan, and I didn't see the show that night either. I don't know why; maybe I was eating dinner after our show? I couldn't tell you, which is a drag. Wouldn't that be great, to say hello? “We played together once upon a time years ago.” I never did it. Oh well.

Did you have any interaction with Letterman or anyone else there while you were out there?

Paul Shaffer. I’ve played with him many times since because of the Blues Brothers world. I once told him, years later, that I played with Dylan on Letterman. He goes, "What? That was the classic show of all time." I remember his comment was, “It was very authentic.” He said those Dylanologist-type folks out there, they think that's a classic moment. I said, "Well that's good to hear."

We were just young and dumb and just open to it all. I think that was probably part of the charm for Bob. Younger guys with no agendas or complaints. I think that there was probably something refreshing about that to him.

Like I say, this old music and blues connection, which I'm deeply into to this day, was surely some of it too. I remember one time I had gone to the South looking for records and I met Gus Cannon and Furry Lewis and Henry Townsend and Yank Rachel. I sought out all these guys right after high school. These guys, still-living, were heroes of mine. I remember talking to Bob about that. We were talking about Robert Junior Lockwood. He's famous for having played with Robert Johnson as a young lad, but it means more than that to me. He's his own entity as well.

This is the thing about Dylan. He probably knew many of these folks. He probably played with Furry Lewis at different festivals and Gus Cannon, guys like that. So we're talking about Lockwood. I said, "I went to his house in Cleveland, and he wasn't really nice to us. He stole my pen. I asked for his autograph and then he asked me for the pen." Dylan says, "Maybe he was just having a bad day."

Dylan was very kind in that way. He clearly saw the whole picture. I sense he was charmed by us a little bit, probably reminded him of different people he had known when he was a bit younger. That's how I view it. I remain grateful for the entire experience.

This is a left-field question, but it jumped out watching the videos. Was the headscarf your trademark look or was that special for this show?

Isn't that great? He asked me to wear it. At our New York rehearsal, he said, "Why don't you put on a headband or something?" I said to myself, "I'll give you a fucking headband."

It was his idea?

In those days, I did crazy stuff like that all the time on stage anyway. No biggy. That wasn't even my natural color hair at that point. I have lighter brown hair really. I was dying my hair, wearing makeup, wearing weird shit on stage all through the '80s, just as a thing to do. Like randomly changing my stage name as well? [He had Letterman introduce him as "Just Ingest Ing," which sounded like "Justin Jesting."] So, I wore that. It's kinda goofy, but that was his request. I like it. I certainly wasn't going to wear one of those thin little tennis headbands.

It looks great. It jumps out from the video.

You remember it. Whether you like it or not, you remember it. I knew one thing at that point: You're going to be on TV, you want to be remembered.

Thanks JJ! These days Holiday plays backing the Blues Brothers as well as in his own group The Imperial Crowns.

ICYMI — Recent Entries:

Stories in the Press: Pittsburgh 1965 (w/ Joan Baez)

On today’s date in 1965, Bob Dylan played the first of two all-but-forgotten shows in Pittsburgh, his first time in the city. They’re all-but-forgotten for a simple reason: No recordings. But I decided to see what info I could piece together from contemporary news reports.

Notes from the Road in North Carolina (by Jon Wurster)

On Sunday night (St Patrick’s Day, which is relevant), Bob Dylan brought the Rough and Rowdy Ways World Wide Tour to Charlotte, North Carolina. The next night, Bob played a few hours east in Fayetteville. Also in both places: Friend-of-the-newsletter Jon Wurster, for once not on the road himself with The Mountain Goats or Bob Mould or…

Burning CDs and Printing Lyric Sheets for Bob Dylan

As regular readers know, in addition to the musicians Dylan’s played with, I love talking to behind-the-scenes people on Bob tours. True, their jobs usually don’t involve as much direct interaction with the man himself, but I’m always fascinated to learn how putting on a Dylan show works.

It was a pleasure speaking with you Ray. I hope this helped shed some bits of new light on things for you here. I haven’t really spoken out about this period in any meaningful way since it occurred. After a full 40 years now, I’m glad to have been able to recall some almost forgotten details enough to provide you a tangible feel of it all at the time it happened. It was fun. Thanks & best wishes, JJ Holiday.

I really enjoyed last year’s interview with Tony Marsico, and this is another super interesting conversation. Of course I love the Letterman performances. Thank you!