Going Show-By-Show Through Bob Dylan's 1974 Comeback Tour with The Band

1974-01-03, Chicago Stadium, Chicago IL

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

Bob Dylan and The Band’s 1974 comeback tour started nothing like Before the Flood.

That live album, the best-known representation of what was simply christened Tour ’74, is all hits. Wall-to-wall. Even the Band tunes are almost all widely-beloved classics.

The very first song they performed on Tour ’74, though, was not a hit. It was the deepest cut they performed across all 40 shows. You could argue it’s the deepest cut Bob Dylan has played ever. And that song was…“Hero Blues,” a Freewheelin’ outtake he’d barely played live even in his folk era. It’s a shock he even remembered it existed a decade-plus later.

Here is a shaky video of that moment, the very obscure very first song on Tour ’74:

Compare that to the original version. Right from the tour’s first moments, he’s unleashing an acoustic-to-electric reinvention as dramatic as “I Don’t Believe You” in 1966. It used to go like that…

“Hero Blues” does not appear on Before the Flood. That album largely represents the other side of the tour: Giant, crowd-pleasing singalongs in faceless corporate arenas. It bummed Dylan out. “I think I was just playing a role on that tour,” he told Cameron Crowe years later. “I was playing Bob Dylan and The Band were playing The Band. It was all sort of mindless. The only thing people talked about was energy this, energy that. The highest compliments were things like, 'Wow, lotta energy, man.' It had become absurd."

But I think there’s more to Tour ’74 than bad corporate-rock vibes. So, for its 50th anniversary this month, and in tribute to the recent passing of Robbie Robertson (almost as pivotal a force in making this tour happen as Dylan himself), I’m going to be diving deep. Way deep.

Like I did with Rolling Thunder a couple years back, the next year’s tour where he rebelled hard against this megastar mode of travel, I’ll be going show-by-show on each date’s anniversary. One-half of them (like this one) will be free. One-half (like tomorrow’s) will be for paid subscribers only. All will, of course, come with the recordings.

Upgrade to a paid subscription to get the complete Tour ‘74 series delivered right to your inbox (plus access to the entire Flagging Down archives). Just $5/month, and two months will cover the entire series.

My goal is to go deeper than the big-picture stories you read about elsewhere: The limos, the private jets, the burnout. I want to explore what actually happened at every show. I’ll be going off tapes as well as contemporary press reports and photos. What was the scene like in the room? What songs changed from night to night? What did Bob and the Band do during the daytime hours? (That is, when they weren’t playing shows then too; this tour features a number of two-show dates, afternoon and evening shows each running two-plus hours. No wonder they felt burnt out.)

First up: Chicago!

Dylan and co. flew in the day before the first show. That night they swung by the Earl of Old Town folk club, a home base for Chicago songwriters like John Prine (who got discovered by Kris Kristofferson there in ’71) and Steve Goodman—both of whom were at Bob’s Chicago show—to hear local folk hero Fred Holstein perform. Briefly.

The following night, 50 years ago today, Dylan opened his grand comeback tour at Chicago Stadium. When it was built in the 1920s, it was the largest indoor arena in the world. It still held hockey games; in fact, the ice under the rubber mats on the floor was so cold that tour promoter Bill Graham had to make last-minute stage adjustments so the band and crowd wouldn’t freeze.

They tried to make the generic giant arena stage feel homey. In this first of his many Rolling Stone dispatches from the tour, writer Ben Fong-Torres describes the setup:

On opening night, the first discovery for the audience was an attempted coziness on the stage, through props reminding one of Neil Young, Martin Mull and an Uncle Sol furniture sale. There wasn’t just a rug, some candles, a sofa and a coat rack, but also a Tiffany-styled table lamp, a roll-top desk, an antique rocking chair, a set of conga drums, a bunk bed with frumpy blue mattresses, a multi-colored wood chest housing a fire extinguisher and, at the bottom of the stage steps, a mat reminding the stars to Wipe Your Feet. It was just Dylan and the guys playing their music for 18,500 drop-ins.

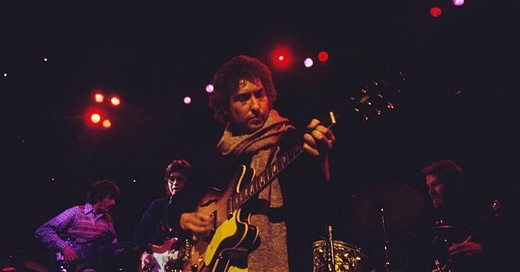

Graham joked to another reporter, “the furniture was from my home. I need the money.” I haven’t found any photos of the bunk bed, alas (and I don’t think it made it beyond Chicago—a lot of these stage trimmings were quickly dropped). But you can see that Tiffany-style lamp and the coat rack in these shots:

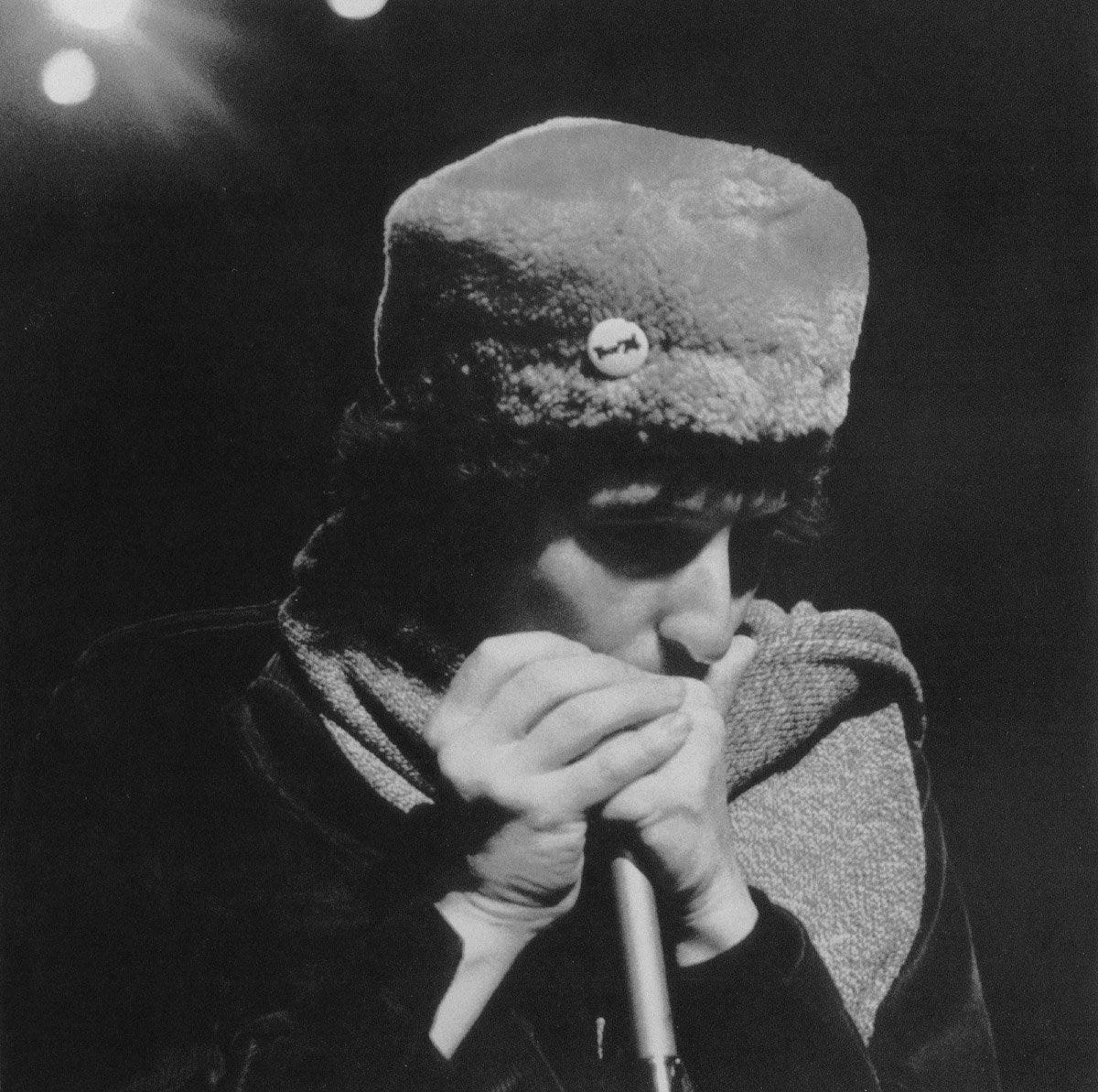

Levon Helm writes extensively about this concert in his memoir This Wheel’s on Fire. He said that stage setup “looked like some old Klondike prospectors’ camp.” And he noted that group “felt very unready when we hit Chicago, despite a long soundcheck that morning where we ran through the whole show except for Bob’s part alone.” Here’s a photo from that soundcheck. Bob’s enormous furry hat (this is January in Chicago, after all) appears to be sporting a Tour ’74 button.

After “Hero Blues,” that wild acoustic-gone-electric opener, Bob and the Band played “Lay Lady Lay” (which gets a roar of recognition from the crowd) and “Tough Mama” (which, being a new song, doesn’t). Then—and this is one way opening night differed from any other show—The Band started playing some of their own songs, and Bob stayed onstage to jam along!

At all other shows the sets would be distinct, with Bob leaving during the two extended Band portions of the show, but here they alternated tunes and all stuck around throughout. In his book Testimony, Robertson says after this first show, label boss David Geffen advised them that there was no reason to Bob to stay onstage playing rhythm guitar during the Band tunes. Which is reasonable advice, but it seems strange that night after night The Band is playing “I Shall Be Released” and “This Wheel’s on Fire” while the man who (co-)wrote them relaxes backstage. And why not give Bob a verse of “The Weight”?

The Band’s sets, with Bob in tow, also featured three songs they would immediately drop: “Share Your Love With Me,” “Holy Cow” (both covers off their then-most-recent album Moondog Matinee), and “Life Is a Carnival.” Chicago night one was the only time they’d play any of the three on the tour.

After a first set that included Bob’s first-ever performance of the song he has since performed more than any other, “All Along the Watchtower,” they took an intermission. Helm describes the scene backstage:

When he finished, Bob stepped up and said, “Back in fifteen minutes,” and we collapsed into the dressing rooms in total exhaustion. The amount of energy that playing for those big audiences required was incredible. I know I felt wrung out like a sponge. I noticed my hands shaking when I lit a cigarette.

I looked at Richard [Manuel]. He’d come out of a dark period, and we all worried about him. His shoulder-length hair was wet, but he smiled and gave me a look that said this was going to work. For the umpteenth time, I thanked the heavens for having Garth Hudson in the band.

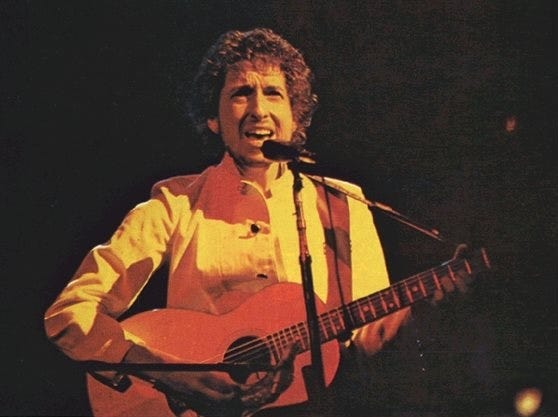

Dylan returned for his first of many post-intermission solo sets in a change of clothes. Black denim jacket for the electric set, white tunic for acoustic. Not the sort of shirt you see him wearing much. He looks like The Beatles off to visit the Maharishi.

The solo set featured another debut, the Planet Waves outtake “Nobody ‘Cept You,” and another song dredged up from his early folkie days, “Song to Woody” (first time he performed it since 1962, and one of only two performances on the ’74 tour). It also featured another debut of a sort: The first time the line about the President standing naked in “It’s Alright Ma” got a huge crowd response. Nixon was mired in Watergate at the time; he would resign the presidency that summer. Decades after Watergate, that line would still invariably get a big cheer.

The cheering was the least of it that night. Newsweek reported, “The lyrics even inspired one man to rip off his clothes and declare his Presidential candidacy on the spot. He was immediately tackled by rock impresario Bill Graham, producer of the tour.” [Update: See comments for more info on the “It’s Alright Ma” streaker]

Other than that streaker, the crowd was reportedly subdued. The Chicago Sun-Times reported it was “the oldest audience at a stadium rock concert since the Elvis Presley shows, and even more well-behaved… Only two or three times in the whole show did everyone leap up the cheer and scream.”

Another set of Band tunes followed Dylan’s solo set, which featured its own live debut: the Rick Danko-sung “When You Awake,” off their 1969 self-titled album. This tour was the only time they’d ever perform it. The show then closed out with a murderer’s row of live debuts: “Forever Young,” “Something There Is About You” (both new songs at the time), “Like a Rolling Stone” (the only one not a debut), and, finally, “Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I'll Go Mine).” Soon they’d be playing that one to open and close every show, but for now it was just the big finale.

Spirits were high after night one. Robertson told Newsweek’s Maureen Orth, “we were booed off of every stage in Europe. What happened tonight in Chicago is so reassuring for us.”

1974-01-03, Chicago Stadium, Chicago IL

Tomorrow: The tour continues in Chicago with some setlist shakeups, including the live debut of one of Bob’s most iconic songs. Available to paid subscribers only. [Update: Here’s the link!]

UPDATE: More info on the "It's Alright Ma" streaker, from someone who knew him:

I’d known Harvey for a few years, maybe since '67 or whatever. Harvey was sitting in front of me in the first row. Harvey was not a stupid street hippie; he was really a bright guy. He was going through a really bad divorce and was doing some unusual drugs. Bad shit, I think, stuff he shouldn't have taken.

The concert hadn't started yet. Bill Graham came up and talked to Harvey. He said “Harvey, I want you to behave yourself.” Harvey said, “But I've got to tell Bob I'm running for president!” Bill said, “I’ll work on that, but you have to behave yourself tonight.” And of course, you know what happened.

Bob gets to the line “Even the President of the United States must sometimes have to stand naked.” Harvey is wearing a sweater and a pair of pants, no underwear, and he drops them. He stands on his chair, and he turns around and faces the crowd, forming his arms like he's on a cross.

Bill Graham came from the back of the stadium, almost as if he was shot from a gun. I mean, I saw him running up the aisle. He tackles him. Harvey's taken away to, I don't know, the police station. The police say, he didn't belong here, he belongs in a psych hospital. The long and short of it is, is he meets Dylan the next day for brunch. He told me that he sat there and talked to Bob about running for president. Bob looked at him and would occasionally nod, but that was it.

Really looking forward to this series. I saw an early show in Toronto. High energy but it still had a bucolic tinge. When I first heard Before The Flood I was sort of stunned at how different it all sounded from what I had remembered. You could almost hear the coke in the grooves. Looking forward to figuring out at what point in the tour they became a Peruvian Marching Band. I don’t hate BTFlood but i have over a thousand Bob recordings and don’t own it. A reevaluation of the tour will be fun. Thanks, Ray!