Gillian Armstrong Talks Directing Bob Dylan and Tom Petty's 1986 Concert Film 'Hard to Handle'

I said, "Bob, you owe me."

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

Gillian Armstrong is Australian directing royalty. When she directed her first feature, 1979’s Academy Award-nominated My Brilliant Career, the Washington Post promptly dubbed her "the most sensitive and accomplished woman director in the English-speaking world." She promptly went on to direct hits like 1994’s Little Women and 1997’s Oscar and Lucinda (Cate Blanchett’s first leading role), all the while eschewing offers to move to Hollywood and instead becoming a champion of the Australian film industry.

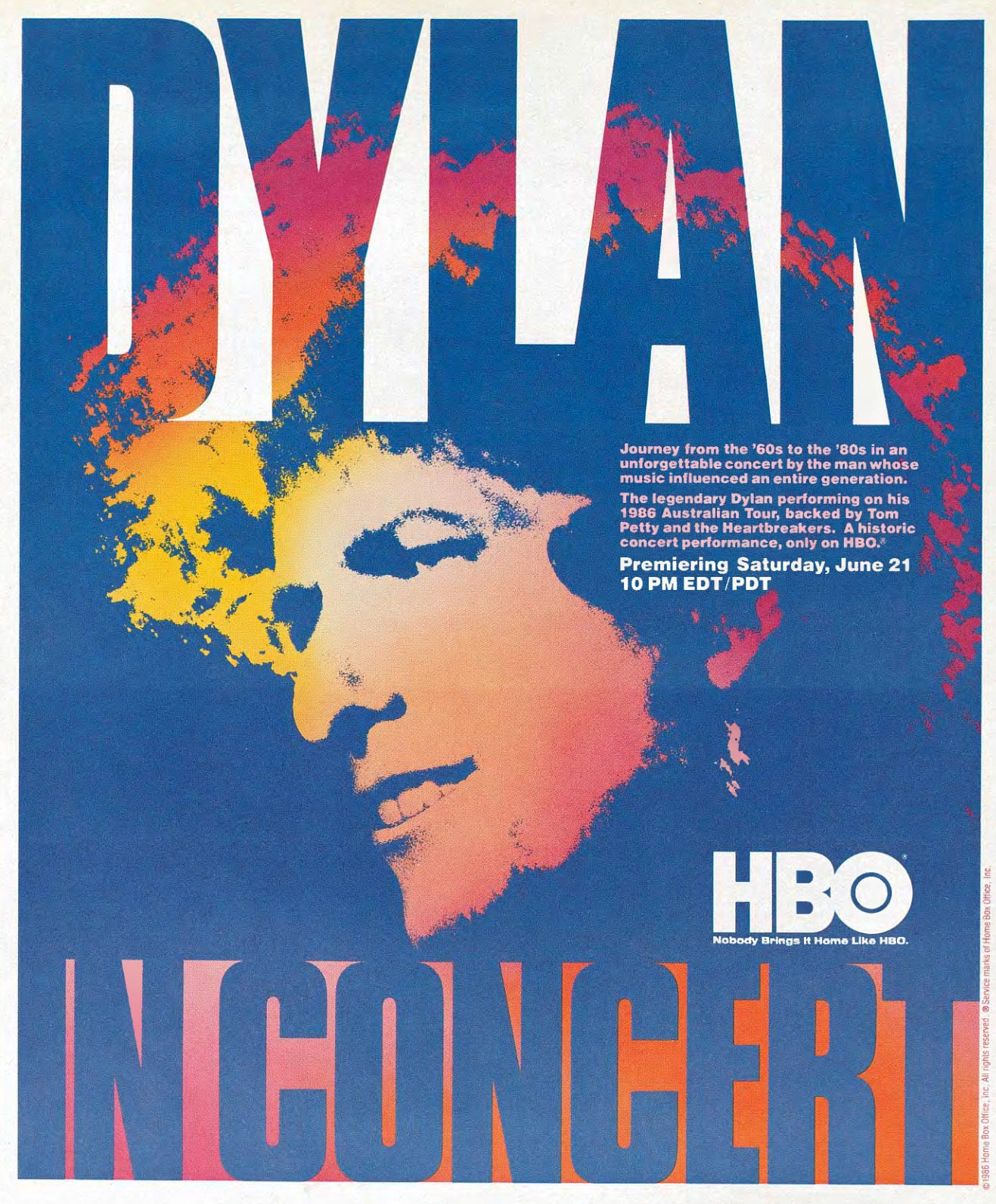

I didn’t talk about any of that with her. When we spoke last month, the topic of conversation was a relative footnote on her resume: Bob Dylan’s 1986 concert film Hard to Handle backed by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. Dylan told interviewers he had selected Armstrong personally to direct it, even though, as she is the first to admit, she had zero experience directing concert movies.

Nevertheless, it’s a terrific capture of one of my favorite periods of ‘80s Dylan. The only shame is that it isn’t longer; it was originally broadcast on HBO, which necessitated a tight one-hour runtime. It was subsequently released on VHS and laserdisc, but never DVD or streaming. However, the Dylan archives in Tulsa have been working to restore it—the one song they show in the Dylan Center theater looks amazing—so hopefully before long there will be a better way to see it than a YouTube bootleg.

Watch the concert if you haven’t already, then read on for my conversation with Gillian Armstrong.

I appreciate you taking a few minutes to chat with me about what I realize is a fairly small blip on your resume.

It is, but it was a very special experience. Also, I feel that it's so forgotten because at that time, we didn't have HBO in Australia. It was never shown here. No one here even knows that I did it. That's why when you approached me, I thought, “I don't have a copy!”

Despite being filmed in Australia, it didn't actually air in Australia?

No. I'll give you the background. I thought you probably wanted to know: Why was this made in Australia?

His management thought that before the tour went around America, making a concert film would be a great way to promote Bob and Tom. The tour started in New Zealand. I flew over there to meet them all and to watch the first couple of nights of it. Then they did Sydney. I think maybe they went to Perth [and Adelaide and Melbourne], and then they came back to Sydney.

Elliot [Roberts], who was Bob's manager, came up with the idea. It'll be on at HBO, and therefore get some excitement in America before the tour there. He then started thinking about what Australian filmmakers could do it, because they didn't have the biggest budget. The Australian film industry was actually quite hot then. The other thing was that all television in America at that time had to be shot on 35 millimeters, which is what you shoot a feature film on. Really expensive because of that.

Elliott had seen My Brilliant Career. I’m not sure that Bob saw the whole film, but he definitely had seen some of it because he did talk to me about Judy Davis, who he thought was excellent. He made jokes about wanting to meet her. They approached me and asked whether I'd be interested in directing it.

Elliot just thought the key thing would be for me to meet Bob as soon as possible, so they flew me to New Zealand. He said, "Can you just travel with the band?" He put me in the plane sitting next to Bob, so that we could talk about it. That was the whole premise of how it started.

Were you a big Dylan fan, a casual Dylan fan, not at all a Dylan fan?

I was a casual Dylan fan. But I heard the concert night after night, so by the end, I knew every song by heart and loved them. In retrospect, I think it was actually quite good that I wasn't star-struck, because I saw how other people behaved around him.

His fans are so full-on. There were film producers in this country who had been fans since uni who were literally calling me at home. "Is there any way you could get me in to meet Bob?" I realized that the fandom was crazy, crazy. I think that was good that I could just come in as a respectful artist and talk to him one-on-one.

I’ve realized over the years with other famous people that I've worked with, there's a terrible trap with celebrity that nobody tells you the truth anymore. I think Bob realized after a while, he could just trust me. I'm quite outspoken. I mean, I know how to be a diplomat, but I'm not a bullshitter. I think he quite liked that in the end.

He played a few concerts in Sydney. I went along to those. The DP would talk about the lights with me, our sound technicians came, all that. Then they went around Australia. Then they came back in a week's time to do two more concerts in Sydney. They were the ones we were to film. I had two nights to shoot, and then I talked them into giving me another half a day so we could get all over the stage without blocking them from the audience. So I had another half day to do some extra close-ups and things like that.

You mean they performed a concert, or some songs, with no audience? Just cameras?

Some, yeah. I can't remember which. We did do a few pickups, although it's funny when I looked at it again yesterday, I thought, “I can't pick where there might have been a shot that was a pickup we did without the audience.” Obviously, that's the art of editing.

I've seen it a bunch of times, including last night. I never noticed that.

Yeah, people probably thought we did it all in one night. We did it two nights for two reasons. Bob would never tell us exactly what the songs would be or their order. I really tried to at least get a list of what the songs were because we thought, well, maybe there could be different lighting on different songs.

[Filming two shows], in the end, gave him more choice about which ones would finally be in, or if they felt they played one song better on, say, the Tuesday night to the Wednesday night, then we'd use the Tuesday night one. Or if I thought we'd shot something better, I would put in the one that had the coverage.

Were you getting any in guidance or direction from him or anyone else, or did you have free reign to shoot it however you wanted?

Well, I talked with Bob about it. A couple of times, I came up with some ideas to try and make it a bit artier. Or should I do some stuff behind the scenes? He really felt it should be very, very simply just one of the concerts. Because I'm a creator my own right. I said, especially when this whole fan madness happened, "Maybe there should be something at the end when you're playing the last song, suddenly like 100 people all dressed as you, all with the guitar, come on. They've all got your hair, they've got the vest…” He just said, "No, I think we'll just keep it simple."

When I looked at it yesterday, I was like, "Ehh, it is a bit boring…" Whenever I look at something that I made, whatever it was, 35 years ago, I think, "Oh, it could have had more cuts. It could have been a bit faster."

I tried to talk to him about any particular angles he preferred about himself, side on, or front, or low. He was open about that; he wasn't really prescriptive. The main thing he did with me throwing out some wilder ideas, and stuff about maybe talking to him or seeing him and Tom rehearse, was just, "No, let's just stick with the concert."

If I'd had all that stuff with him talking, it could be on in cinemas now. I've just been to see The Band film [The Last Waltz] with a full house and incredible sound. They're all being remastered.

You mentioned the 35-millimeter thing for US televisions. I saw a reference that this shoot was the largest 35-millimeter shoot in Australia history. Was that because it was aimed for US TV?

Yes. Probably the thing about the amount of footage because I had six cameras. That was part of the thing that I had to work out. In the beginning, I didn't know if I only had one night with them or the two, so we had six cameras, and they're rolling film. It's very expensive. Australian television, they would either shoot on video cameras or on 16mm which is half the price.

We also got one of the first Louma cranes. That's a giant crane. Now they're partly operated by robots, but at that time, we had a hand operator.

There's that amazing crane shot near the beginning of “Knockin' on Heaven's Door.”

Yeah, and no rehearsal. The crane guy just went with the music; he did a really fantastic job. I looked up the IMDb because I couldn't remember who all the camera operators were. Nearly all our operators went on to shoot major feature films all over the world. That was Danny Batterham on the Louma. He did a wonderful job. We've always had great camera people. It’s a small country but really always had great talent.

That was the thing, because by then, we'd seen a lot of rock and roll [movies], Woodstock or whatever. It was always a handheld and so on. Our idea, because it's the '80s, I said, "Why don't we do something that's simple and classy and has lovely moves?"

We sent the first or second cut to LA for Bob to see, or maybe I went with him. I definitely went to LA, and he and Tom had a screening and saw it. His first comment was, “Too many shots for the backup singers.” We had a lot more. The editor John Scott had done a lot of music stuff and was a diehard Dylan fan. I thought he was the perfect editor because he knew all the songs and he really, really understood the music. He and I were both in love with the beautiful backup singers.

I love the shots of the other singers. I wish there were more.

Well, there were a lot more. That was the one thing Bob said: "Maybe a few too many." We might've gone over the top, because they're all so beautiful as well. So we pulled that back a bit. I think really, that was his main comment. He was really happy, not picky. God, I've met a lot of producers over the years who go on and on and on with minor details.

We ended up having quite a lot of conversations in the end about the final cut. He rang me every night to talk about it. The big thing was that he wasn't sure which song to open with. I had chosen one of the ones that had a beautiful Louma crane shot. It was Bob on his own with acoustic guitar in the spotlight. It had like a reveal. It came across the floor spotlighting him and you just saw the back of his head with the halo with the light. Now when I talk about it, sounds a cliche, but at the time, it was beautiful.

Like the famous album cover. That's a great idea.

Yeah, and it wasn't planned, but I had a radio mic and I basically told the camera guys to go with the music and just move. I put that in as the opening shot. Then he called me back in Australia and said he'd been thinking about it, and he thought he should open with “In the Garden.”

I've got to tell you when he did “In the Garden,” I definitely got the sense that nobody in the band liked the song. None of the team. They did the worst lighting on it, red and green. I sorta got this feedback that, it's not going to be in it. So I only ran three cameras. I did the worst coverage as well; I just had a close-up and a wide shot or a medium shot or something. So for him to come back and say, "Oh, that's the one I want to be the opening—"

I said, "Well, Bob, the thing about TV is, especially if part of the idea of getting onto HBO is to widen your audience, if people turn on and this is what they see in the first four minutes, they'll turn off. They won't keep watching." So I had that first conversation and said, "I'm telling you now, this is not the right way to open. Think about it, and we'll talk tomorrow."

He rang me back and said, "Oh, no, I've shown it to a few friends and they all like it." I thought, “Well, your friends are just going to tell you what you want to hear.”

Then his management rang me, secretly, behind his back, and said, "Gill, please, please talk him out of this!" I don't know if Bob knows this. I'm like, “None of us like it, you're right! You're giving this whole responsibility to me?”

And then he rang me again to talk about it. He was never petulant or anything; we had lovely conversations. He was sort of wanting to really understand. I was telling him why I thought [“In the Garden”] shouldn't be the one that opened, that perhaps it should be the other one that had a fantastic shot.

I said something and as it came out of my mouth, I knew I'd said the key thing to kill it. What I said to Bob was, “With the opening of anything, a movie, a show, you always put the best forward.” As soon as I said “always,” what people always do, I was like, no, no, what have I done? Like, I'm talking to one of the world's greatest rebels. “Always” killed it.

I had to say, "Look, in the end, it is your film and it's your vision and you have to be happy.” But I said this thing sort of as a half-joke, I said, "Bob, you owe me. One time, I'm going to want a song for a movie and you're gonna have to give it to me." He goes, "It’s a deal."

As it turned out, a year later, I was making a film in Australia called High Tide starring Judy Davis. I remembered Bob had asked me about Judy and thought that she was wonderful. I got the production office to send his management a message saying, "Dear Bob, I'm doing this film with Judy Davis, she's a huge fan of yours and there's a scene in the film where she's meant to be drunk and singing. She really, really wants to sing one of your songs, ‘Dark Eyes.’ This is a low-budget indie Australian film. Is there any way we can have it?” I got the message back: Yes. We had to pay four dollars or something.

That was her choice to do “Dark Eyes”? That's hardly a big hit.

It was her choice. I know she's a Dylan fan and knew all his songs. She thought that in the story, and she was right, her character's unraveling, all these things have gone wrong. Anyway, so I've got to say that he's a man of his word. He gave us “Dark Eyes” for High Tide.

Standing by the side of the stage night after night, watching them, they were so hardworking. A couple of times, I did go by to chat to him at his hotel in Sydney. They were always working on something or rehearsing something. He did a whole heap of soundchecks and so on. People sometimes think that once somebody's famous, they don't really care anymore, but he was very conscientious and so was Tom and all the band.

It was a pleasant experience, but I don't know how it went [when it aired], actually. I never really heard. I'd sent Bob off to America and he'd chosen the title Hard to Handle. I sent the assistant to the video house to do the download for HBO, and Bob came along to see the titles, and everything. That was the last one to go back, "Bob changed the title [lettering]. He's chosen some kindergarten one that is wobbling." I'm like, "Oh well, okay. It's his film." [laughs]

Do you know where the title Hard to Handle came from?

I don't know. I think he must have come up with the idea early on, because we certainly didn't have long discussions about that.

There was one thing with the recording that I should tell you. So they did the first few shows in Sydney. Now both mornings, they did soundchecks. I went in because I was in there also with the camera team working out what we’d do when they came back. I was walking around on the stage and looking at possible shots and angles.

The first night with an audience, I went and stood at the back and I thought, “It sounds terrible.” Bob had been so conscientious and worried about the sound, but all that was about the foldback speakers [stage monitors]. He had no idea. So he's playing, and the audience were just restless, unhappy. It didn't sound very good. Then the reviews came out and they said how it didn't sound good and that the band's off.

I rang the Australian promoter, Michael Gudinski, who I knew because we did this little rock musical Starstruck. I said, "Michael, these reviews are terrible. There'll be nobody in the audience when we shoot.” I wasn’t going to show too much of the audience, but I knew that Bob and Tom would be down because they wouldn't have the joy that you have when you've got an audience that are excited and with the band. They’re not going to play as well if they’re not getting that response from the audience.

I finally got one of the reviews from the Sydney paper and I gave it to Bob's assistant, and I said, "You have to show this to Bob, because he has no idea." I just felt really sorry for Bob that he wasn't going to be selling tickets, and I also thought for us that the energy's going to be down with Bob and Tom because the audience is down. Because everyone was hiding the reviews from him. They were hiding them!

I wonder if that's the one where, at at the first show you shot, he references a bad concert review. He even quotes it. [Listen below]

Well, guess what? That’s because I said to the promoters, “You've got to tell him about these reviews, so they fix the sound for the audience. He doesn't know. He's hearing fantastic sound on the stage, because I was stood on the stage with him. He doesn't know why the audience aren't cheering and everything. You've got to tell him.” “Oh, we’re not going to tell him.”

That's how people behave with a celebrity. It's not that Bob had a name for like-- there's certainly other artists that everyone knows have incredible tantrums or whatever. So I'm the one that gave the review to his assistant and said, "You must get Bob to read this and for him to get onto his technicians to fix the sound in this stupid festival hall.” It was an old barn renowned for not having great sound, so you have to really work at getting good balance and making the vocal sound rich and so on.

The sound was fixed by the time we were shooting, but it was interesting for me to observe that what happens in celebrity culture. I'd seen it before. Years ago, after I did My Brilliant Career, Stevie Nicks was obsessed with wanting to meet me. She wanted to do a feature film. She was writing stories or something. Like all musicians, they say, "Oh, we'd love to meet you. Come along. We'll be recording from 1:00 AM on."

Anyway, I'm happy to go and watch Stevie. She was recording songs while she was in Sydney. She booked the studio all night for two nights or something. She had these giant boots on. She's singing, and she's thumping the boot while she's singing. I'm in the booth with all the engineers and they’re all going "Oh, the boot is making too much noise." They’re like, [timidly] "Uh, is there any way you could tap your foot a little bit lighter?" She's like, "All right." Then she's singing and they can still hear it. I was like, “Just tell her to take her boot off!”

Celebrities do that to themselves. They’ve snapped once or twice and so no one will ever speak up again.

Was that Stevie Nicks thing during this same time? Because she wasn't playing on stage, but she was on this tour for at least a while. Hanging out basically.

Oh, well, it must have been, yes. Maybe it was a year earlier, I'm not quite sure.

I'm very proud that I did get the sound fixed for the final concerts for Bob and Tom's sake and for the sake of the film. Because actually, even though I saw the YouTube thing and visually, it's terrible picture quality, the sound sounds pretty good. There'd be a 35mm dub with a proper mix somewhere. HBO, I assume, still own it. It is not out on a streaming or anything, is it?

No. I know the Dylan Archives in Tulsa have been restoring it. When you visit the museum, they have a little movie theater and they show one song, “When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky,” restored. It looks amazing.

Someone bootlegged the remastered version being shown in Tulsa, though it looks better in person:

It would look amazing, because it's feature film quality. Maybe I should tell my agents to tell Bob's lot, or HBO if they still own the rights.

Especially in the last two years where you can restore them digitally now. It's very easy just to scan the 35 mil, and then they can really expand the sound. People are going back to the cinemas. We went to see Talking Heads and The Last Waltz in a big old picture house. The sound is incredible, just blasting all around. It was like you were at a concert. But the Talking Heads one was longer, and The Last Waltz, Scorsese did interviews and things, so they had more meat to them. They were feature-length. But they could do it and run it in Bob's archives, that's for sure.

It sounded like you filmed the whole shows though. There must be a bunch of outtakes, a bunch of other songs.

I don't know whether they got the outtakes though.

Did you film basically the whole show?

We filmed two shows. There might have been an alternative version of one of the songs, but sometimes we might've used shots from night one and shots from night two of the same song. Or we might've done an alternative song on one night that, in the end, we didn't put in the film.

Unfortunately, there's not a whole lot of additional material. If there were one or two extra songs that we didn't put in, it was probably because they weren't great. It had to be that TV hour, so there was some restriction on it. There's not a whole lot of extra stuff compared to a documentary where you'd be running around in the camera all over the place.

The shows each had like 25 songs though, and there's only 10 in the final product.

Well, yeah, there probably would be a couple of extra songs that didn't make the final cut. And lots of extra shots of the backup singers. [laughs]

Do you remember any songs that you really wanted to get in there that you didn't?

There wasn't anything that I felt heartbroken about. I've got to say hearing it again, I loved “North Country” and “When the Night Comes Falling” and obviously, “Knockin' on Heaven's Door.” It was great when he was singing with Tom, I thought.

At the same mic. You don't see him do that sort of thing. It looks terrific.

You could feel that they really liked each other and affected each other.

One thing that struck me last night watching it again is just, and I’ve spoke to a couple of the band members about this, it looks like he's having so much fun on stage.

You could see that he really got off on the other musicians. Like he'd turn around to them. They had great keyboard and great lead guitar. And the girls too, he was interacting a little bit with them. Looking at it again, the sound had been fixed with the audience and they were giving that feedback of recognizing the first bar of a song that they loved. There was a really good feeling, which I'm glad we captured.

Another shot I loved rewatching was right when the credits start at the end. All of a sudden, it's from the point of view of the audience. The camera guy's just standing surrounded by people jumping around. You get that burst of energy.

It was a great life experience. I became an even greater fan of him, and I've since watched every Dylan film. Of course, the young actress that I discovered called Cate Blanchett, I thought did the most wonderful rendition of young Dylan in that movie. Have you seen that movie?

Absolutely. I’m Not There. She's the best person to ever played Dylan.

Don’t you think? Yeah!

They got that new one coming with Timothée Chalamet. Another Dylan movie on the horizon.

Oh, is there? Wow.

I've got to say, with all the stuff that I've seen about Bob, and the stories that you hear about famous stars, he was such a gentleman. When they came to pick me up at my LA hotel in a limo, it was he and Tom and probably Elliot in the front seat. Bob jumped out. He came around and opened the door for me to get in. I just thought, “Well, I hope everyone's noticing that Bob Dylan's opening the door for me.”

Then after we had a screening, we actually went to lunch. We were going to a place on Sunset Boulevard. When we got there, it turned out it wasn't open. Elliot said he remembered some place on the other side of the highway, and we all decided it’d be easier to cross than try to do a U-turn to get the other side.

I'm a bit nervous crossing a road in America. You drive on the wrong side of the road to us. But here we are. It's Bob and Elliot and me. We're standing on the side of the road trying to wait for a gap [in traffic]. Then people saw it was Bob, and all the cars stopped on Sunset Boulevard. It was like the parting of the Red Sea. Everyone just stopped to let Bob walk across the road. That's one of my highlights in life. That all the cars came to a stop. How exciting it was.

If only we all had that power to just cross highways whenever we wanted.

Yeah! He didn't ask for it. He didn't put his hand up or anything. It just was like a thing where people were hanging out the window, yelling out, "We love you, Bob."

I said, in every way, it was an incredible experience. It was just amazing to hear him sing and hear the band and stand on the side. Like it was vibrating through me. Also, I really liked Tom Petty, and I thought the band was fantastic, and all the backup singers.

Do you remember what the acoustic song you wanted to open it?

That's what I was looking for last night when I looked at it again. The two solo songs were “It’s Alright Ma” and “North Country.” I think it must have been “North Country.” Although the Louma crane shot that revealed him wasn't in it. We must have cut it shorter. Because it ended up right in the middle of the whole set, we must have thought, "You don't want to suddenly stop and do this giant slow reveal." Sadly, it's not there.

These days, Dylan is known as someone who is very camera-shy. When you go to his concert now, you have to put your phone in a locked bag so you can't take any photos or videos. Was there any sense of that then, any reluctance to have six cameras circling all around him and getting close up in his face all night?

No, because that was the deal. He was very professional. He knew that they needed this to be good. He was willing, as I said, to come back and do pickups.

In most of these rock concert films, you had two or three cameras that are walking around on the stage and standing in front of him. I thought that in the end, the Australian audience, that might turn them off. They might start heckling. So we ended up with long lenses at the side.

I think it's a whole different thing [now]. Half the time, I'm at a concert with everyone with their phones up, and I'm like, "Well, first of all, you're half-blocking my view. Secondly, you're ripping them off. You're not engaging with the music.” They’re not going to turn on Hard to Handle because they've got their own little video at home.

Part of the thing about live music is you should be able to let go and dance and move. Half the time when you see 1000 people holding their phones, you think, "How many of you ever even look back at it?" I can understand why he'd be a bit grumpy with people and their phones. His generation and my generation, we're like, "Don't live your life on your phone."

Do you remember any other changes between the first cut and the final, either by you or by him, or by some combination of the two?

There might have been one or two little things where we said, "Oh, we could tighten that up or we could have another shot of the keyboard or something." My memory was that there were very, very few notes. The biggest one was that we'd overdone the number of shots we had of the singers.

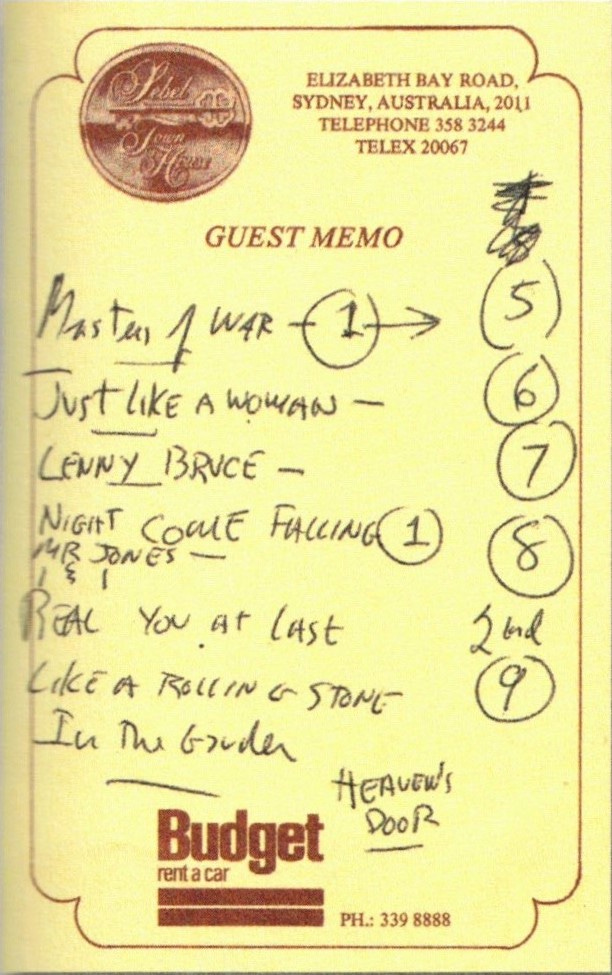

There's a new book that the Dylan Archives put out, and there's a very interesting little notepad that he had written on at a Sydney hotel where he was sort of brainstorming what songs he wants in the movie, and what in order. It says February 1986, so this is before you've made a cut, either just before or just after you filmed.

In the end, every day, we tried to get a list of songs. “What will the songs be?” That was the constant thing. It went on from the time I was in New Zealand to when we first met in Sydney. Then he went around Australia, and he was constantly trying to work out what the songs could be, in what order. I know that finally, that the night we're shooting, we still had no idea.

We got the message from Elliot that he might change something on the night when they're playing. I thought, "We'll just go with it." The whole thing in the end was, what songs, what order? He could never really decide.

We might have changed the order when he first saw the cut. That probably didn't stay in my mind because we'd all got so accustomed to him changing his mind about what the order would be, but the key thing, the one that I thought mattered the most, was how to open it. As a filmmaker, I wanted to open it in some really strong visual way and, for him, that it should open in a really great musical way. Literally to say, “Here's Bob again and you can go and see him.” When I listened to it yesterday, I thought, "Well, ‘In the Garden’ is a bit of a dirge, but he's got his heart in it.”

Not only does he open with “In the Garden,” but the film literally opens with this odd little speech he gives about your hero might be Mel Gibson or whoever. Which is really a weird way to open. Jumps you right in.

You know Mel is Australian, so that was pointed to the Australian audience. In my first American film [Mrs. Soffel], he played with Diane Keaton. Bob was having a dig at who would Australians have as their heroes. He probably didn't know any of our cricketers.

Thank to Gillian Armstrong for taking the time to talk! Bonus thanks to Dag Braathen for providing some of the visual assets here.

If you want to learn more about Dylan and Petty’s run together, check out my interviews with band members Benmont Tench and Stan Lynch and tour manager Richard Fernandez.

And stay tuned next week for another helping of Dylan/Petty content: A look at all the (many!) songs they covered on that tour, many golden oldies Bob’s never performed before or since. Subscribe to get it sent straight to your inbox.

Ray, this was so good!!!!!!!!!!

I enjoyed reading this, thanks to you both!..

"Maybe there should be something at the end when you're playing the last song, suddenly like 100 people all dressed as you, all with the guitar, come on. They've all got your hair, they've got the vest…” He just said, "No, I think we'll just keep it simple.".. This made me laugh. Haha.. I strangely feel like I had read this previously in some kind of way. Maybe I dreamt this.

I think I can see why Bob would want to open the film with that song. It seems quite a rousing first song to me anyway. If people aren't drawn in by that, and turn off, so be it.. (also it has a sense of you are arriving in the middle of something, just a glimpse of what is happening) ...

This reminds me, when I first saw Hard to Handle I thought maybe there was a 'part one' that I missed. The way it begins.

The title, Hard to Handle, I have always kind of associated with 'Handle with Care' .. but of course that song came a couple of years later.

Is it the case that the footage of all the other songs played at the two shows wasn't kept?