G.E. Smith Recalls the First Years of Bob Dylan's Never Ending Tour

"He just did whatever he wanted, and he knew that I would follow him"

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

G.E. Smith was the first guitarist of the Never Ending Tour, and the first bandleader too. He came aboard from his longtime gig at Saturday Night Live musical director, where he could often be seen with his distinctive blonde ponytail playing in and out of commercials in the '80s and '90s (he made a cameo earlier this month on the 50th anniversary special). In fact, he remained with SNL his entire time on the road with Dylan, flying back and forth to New York along with drummer Chris Parker, who I interviewed a few years ago.

I’ve been wanting to talk with G.E. for ages, and a few weeks back we finally connected for an in-depth interview all about his time on the road with Dylan. He was only there for a few years, 1988-1990, but in many ways he set the template for the entire Never Ending Tour to come (though, as he notes, they didn’t call it that). These days he continues to perform all around the world; next up are a few Northeast dates alongside another former interviewee, Larry Campbell, in their “Masters of the Telecaster” concert series.

Here’s my conversation with G.E. Smith, edited and condensed.

I was watching the new Saturday Night Live music documentary last night and spotted you playing with Al Green.

I love Teenie Hodges, who played guitar on a lot of his stuff. I’ve studied his playing. When we were doing this soundcheck on Thursday, before the show, I was just getting my sound together and I was playing some Teenie-style stuff. [Al] came over and went, “Wow, I haven’t heard that stuff in years!” That made me feel great.

One other random SNL thing before we get into it, this one tangentially related to Dylan. I was watching a while ago the Harry Dean Stanton episode. There was a moment during the monologue where you guys were up on the faux marquee, and he climbs up. It’s you and Tony Garnier doing a blues song with Bob’s buddy Harry Dean Stanton.

That was my first year. He comes climbing up the ladder. We were afraid he’s going to fall off. He may have had a drink before the show.

That’s a famous SNL story, Harry Dean boozing it up with The Replacements backstage. Why was Tony there? He wasn’t a part of the SNL band.

Tony Garnier was a sub. At that time, my great friend T-Bone Wolk was the bass player.

Almost the first bassist of the Never Ending Tour too. So let’s get into it. You have one of the all-time great stories of meeting Bob Dylan. Which you’ve told before, but we have to start there before we go deeper. Dylan’s manager Elliot Roberts calls you at SNL, says “Get a band together,” you recruit your SNL bandmates Chris [Parker] and T-Bone. What happens next?

Elliot had been my manager for a brief time in 1980. Even after we weren’t professionally involved anymore, he would call me a few times a year just to say, “How are you doing?” He calls up and says, “Hey, Bob is coming to town tomorrow night. Can you get a bass player and drummer and be at Montana Studios?”

I thought that Bob just wanted to play. I had met Bob very briefly at a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame dinner. Just the briefest of introductions.

Montana was a rehearsal place; there would always be somebody behind the desk who’d tell you what studio you were going to. When I came in to Montana that night, there was nobody there. The place was barely lit up. I thought, “This is really weird.”

I knew where the room was though. We’re supposed to start at ten o’clock or eleven o’clock. We get there pretty early. So we’re set up, tuned, ready to go. The time comes and we’re just standing there on the stage—and nothing. Nobody shows up.

Is Elliot there?

No. Literally no one. No tech guys. No sound guys. No equipment. Nothing. Just the three of us.

At some point, out of the darkness in the back of the room comes Bob. I don’t know if he’d been back there [the whole time] or if he came in through a different door. He was alone; he says hi. He can be very quiet, especially when he’s first coming around people. He gets up on the stage, puts on his guitar, and starts to play. He’s just playing an E chord. Kind of rhythmically, but he’s not grooving. We’re trying to kick in behind him. This went on for some time.

Staying on the E?

Just on the E. He wasn’t singing. This went on for— I mean, it felt like half an hour but it was probably 10 or 15 minutes, which is a really, really long time to play one chord. We never got any kind of heavy-duty groove going or anything. We had a little thing but at a medium tempo, nothing special.

Then he stopped and didn’t really say anything. Then he started playing again. He was sort of singing, but we couldn’t really tell what it was. We were following him.

Me and T-Bone looked at each other like, “Geez. He’s not having a very good time.” You know, we wanted him to enjoy himself, because me and Bone, we were old sidemen. That’s what we do. We know how to make people feel good about what they’re playing. It seemed like he wasn’t having a good time.

Then he walks back to me and T-Bone. He goes, “You guys know ‘Pretty Peggy-O’?” We looked at each other and we go, “Sure!” Exactly at the same time. “Sure!” Like twins. He goes, “Ya do?”

He starts playing “Pretty Peggy-O.” And we did know “Pretty Peggy-O.” That’s one of those songs that you know, whether you know the Dead or the old folky versions.

Would you have known his own version from the debut album?

Oh, of course. I knew that inside out. So did T-Bone.

So we played “Pretty Peggy-O” and it sounded great. Then he started playing. I don’t remember exactly what we played. Supposedly, there’s a tape of that—there’s not. Whatever that tape is that people have, it’s not that night. It’s some rehearsal from some later time. People say they have that; it’s not that night.

I was going to ask you about that. There’s a tape that gets labeled “G.E. Smith Audition Tape,” but “Pretty Peggy-O” is not on it.

It’s not that night. There is no “Audition Tape” because there was no one there to record it. There was no recording equipment on the stage. There was nothing.

We played for quite a while, a few hours. He put down his guitar at some point, and kinda nodded. He said, “Thanks fellas,” something like that, and he disappeared.

We hung around for a while. We didn’t know if he went to take a leak or get a cup of coffee or what he was doing.

Now it’s like, what? Midnight? 1:00 in the morning?

Oh, it’s late. Two o’clock, might even have been later. We’re like, “Wow, that was really fun. We got to play with Bob Dylan. How cool is that?” I went home.

The next day I was in the office at Saturday Night Live, and the phone rings. It’s Elliot. He goes, “Alright, you guys passed the audition.” I said, “What audition? You didn’t tell me it was an audition!” He goes, “I didn’t?” “No, you didn’t. What are you talking about?”

Then he explained. The way he put it was that after Bob had done the two big tours, one of them with the Dead and one with Tom Petty and the Heartbreaker—both great, big, very established bands that had their own way of doing things, now he wanted to get just a trio—guitar, bass, and drums—of guys that didn’t have any stake in that world. That weren’t world famous, super successful bands like The Dead or The Heartbreakers. He said, “Oh, yeah, you got the gig. Rehearsals start in California on this date” and blah, blah, blah.

I was like, “Elliot, I work here at this TV show, remember?” He said, “I’m gonna talk to Lorne [Michaels]. We’re going to work that out.” Then eventually, me and Chris went and played. T-Bone elected not to do it. We started with a different bass player and then eventually got Tony Garnier.

I interviewed Marshall Crenshaw. He was the first attempt to replace T-Bone, even though, as he is the first to say, he was not a bass player.

That’s right. I asked Marshall to come and play. He’s such a great player that I knew he could do it, but [it didn’t work out].

At that first audition, do you remember any other songs other than “Pretty Peggy-O”?

I don’t remember specifically. We didn’t play Bob songs. We didn’t play “Tangled Up in Blue.” It was more that thing that Bob always did that I loved. He would just go into some traditional song.

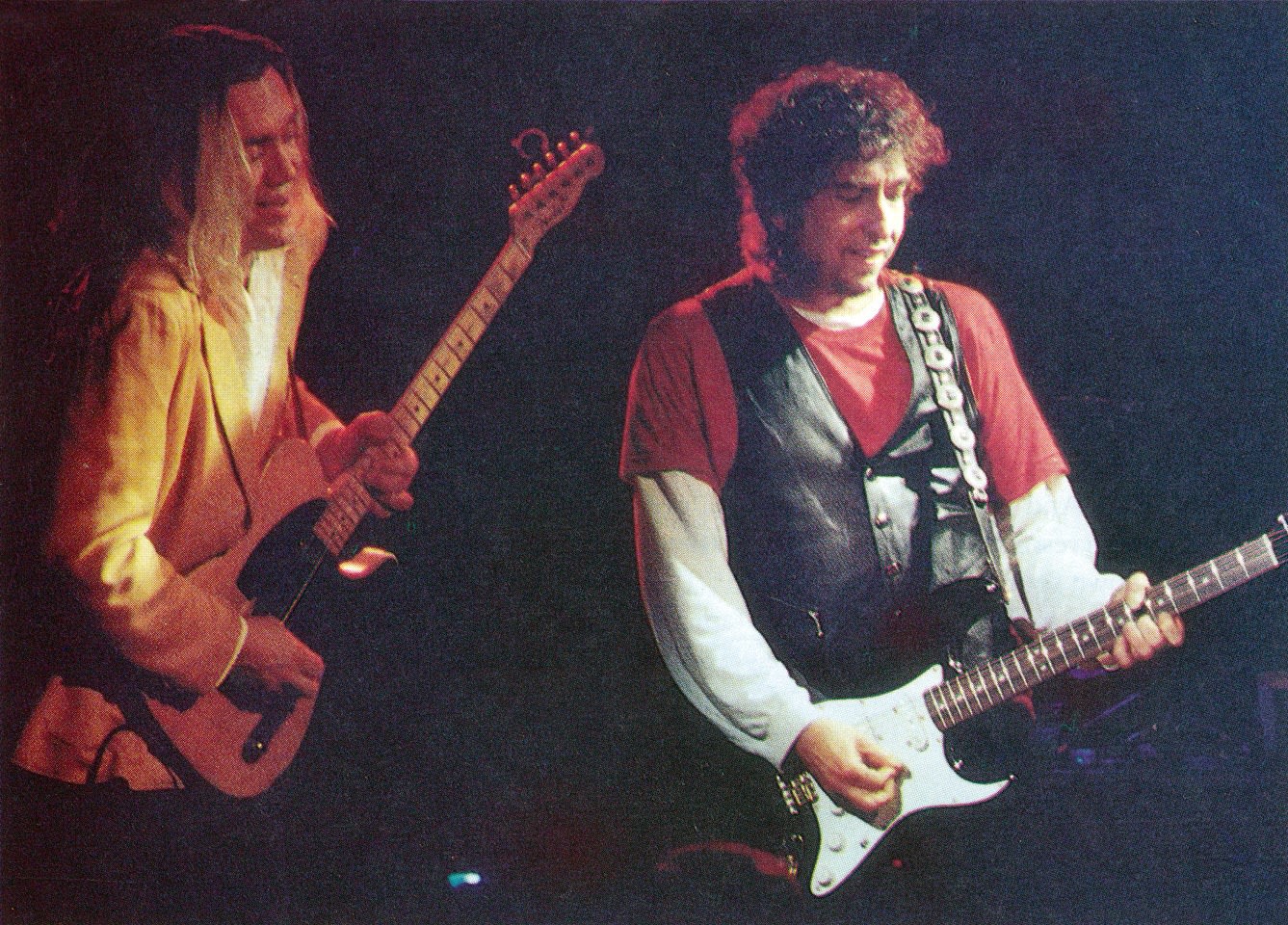

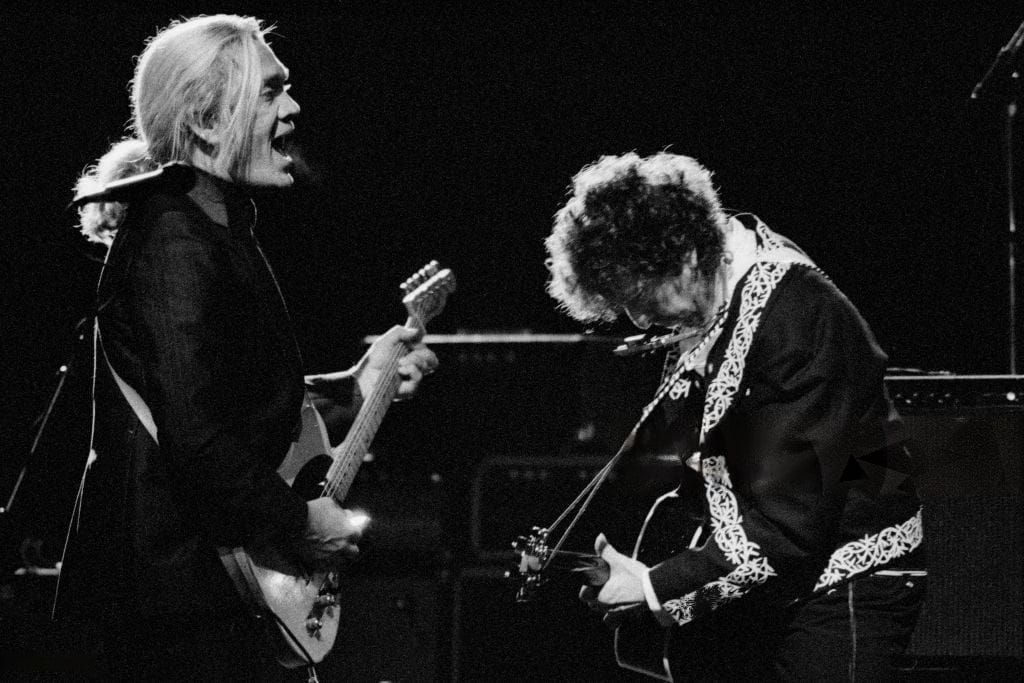

When Elliot told me I had the gig, I had a month or two before we went off and started. I got out all my old Bob photographs. I looked at Michael Bloomfield and Robbie Robertson on stage with Bob. In almost every single picture of them, they’re standing to Bob’s right so they can see his guitar, and they’re staring at his hands. Because that’s what you do. You follow it. You don’t know where it’s going to go.

I love that kind of playing. I think maybe that’s one of the reasons why, musically, me and Bob got along really good. I’ve been doing that since I was a kid with my folky friends in Pennsylvania. I would accompany people, and they’d always go, “You don’t even know that song. How did you play it?” I’d say, “I’d watch your hands.”

One person I spoke to said they felt you were like the Dylan translator. You would be shouting the key to Kenny or indicating to Chris, “Do this.”

When Tony got in the band, because of the virtue of me being over there on stage right being able to watch Bob, me and Tony worked out little signals. I’d give a signal to Tony to at least give him a clue where we were headed.

What do you mean signal?

I had hand signals. After you play with people for a while, if it’s going well, you develop almost like a psychic bond. Like I said, there’s only 12 notes—really only 11 notes, because the first note and the twelfth note is the same. Things go a certain way, usually, unless you’re playing with Charles Mingus or something. After a while, you just develop a shorthand between people if it’s going well. And between me and Tony and Chris, it went well, and we had a great time.

I recently watched the Scorsese Rolling Thunder documentary. I saw Rolling Thunder twice. I went to New Haven Coliseum and Hartford or Springfield, Massachusetts, somewhere else like the next night or two nights later. It was one of the greatest shows I’ve ever seen. Bob’s performance of “Isis” on that Rolling Thunder tour, to me, that’s one of the ultimate rock and roll performances ever, of anything. That’s it.

The things he’s doing with his hands, like the gestures.

Yeah. His gestures, and his eyes, with that white face on. I remember at the New Haven Coliseum, I’m 40, 50 rows back, and I could see his eyes clearly. Just amazing.

That’s a bit of a difference from some of the shows in your era where he is wearing a hoodie in dim lighting.

Yeah. Those were different times.

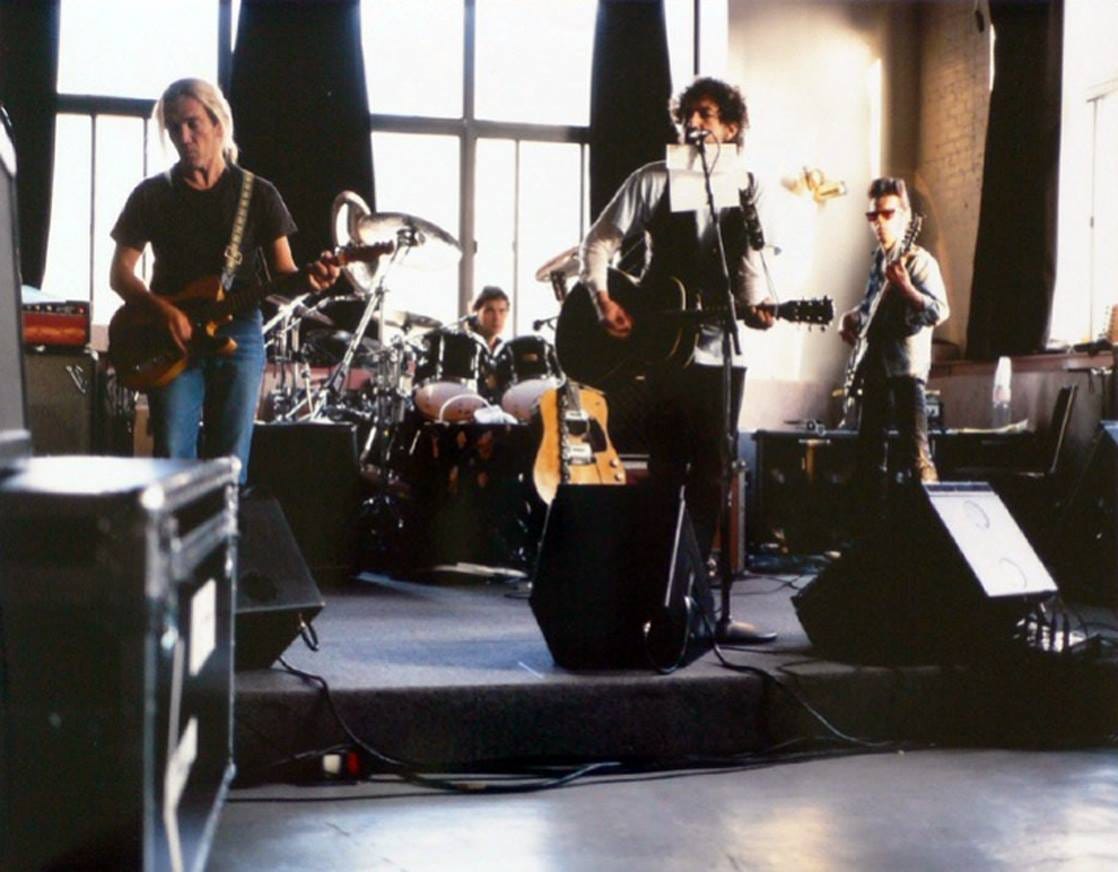

So you do these rehearsals, Kenny eventually lands in the bass spot. What do you remember about the first show? Obviously the big story is Neil Young sitting in.

We go out to California, and we rehearse in Berkeley. Concord was the first gig, and yes, Neil showed up. Drove a truck, carried in his own Silvertone amp and his Les Paul. It was so cool. It was just like a guy coming to sit in.

Did you get to soundcheck with him? Is there any rehearsal?

Yeah, yeah. We played in the afternoon. I mean, Neil didn’t have to rehearse to play with Bob. It’s Bob. You know that music. Neil knows that music as well as anybody.

That was amazing, because I love Neil Young. I love his playing, songwriting and singing, everything. He’d been very influential on my career and as a guitar player. We used to pick those songs apart, all that Buffalo Springfield stuff back in Pennsylvania when I was growing up.

Your first show with Dylan, and now suddenly Neil Young’s there too. Would you have been having nerves? It sounds stressful.

No, it wasn’t stressful. Once I put that guitar on, I’m not nervous. It’s the rest of my life, when I don’t have the guitar on, that I’m nervous. All the other days when I’m not wearing that Telecaster, I’m nervous, but when I got that on, I’m fine, because then I know where I am.

Did you work with Bob on the setlists before the show?

Yes. I would go in the dressing room in the afternoon. Because the band would do soundcheck. Very rarely Bob would come to soundcheck. We would do soundcheck, me and César Diaz would check Bob’s gear to make sure it was working, then the band would play. We developed our own afternoon set of crazy songs.

What sort of songs?

It could be anything. Not Bob Dylan songs. Old rock and roll songs, all kinds of stuff. Then I’d go in the dressing room or I’d go on Bob’s bus. Generally, while I was with him, we started with [“Subterranean Homesick Blues”]. Then after that, anything could happen.

I recently found a box with a whole bunch of those set lists in it. I thought, “Should I send that to that Bob Dylan museum in Oklahoma? They might like that.”

I bet they would.

Anyway, we’d make up a set list. That would be the electric songs.

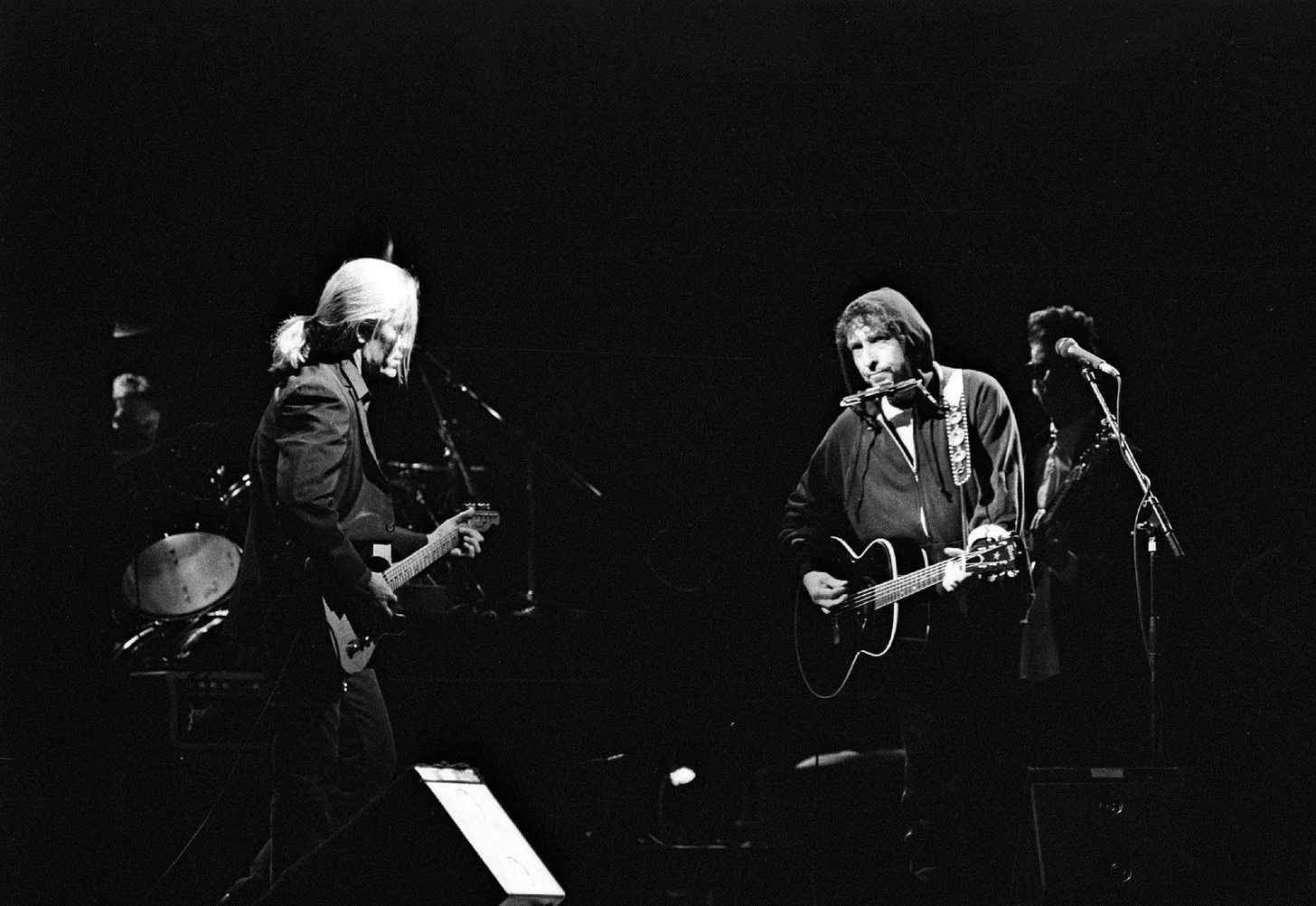

When I was working with him, we would start the set electric. Then in the middle, just Bob and myself would come out with acoustic guitars, and we would play whatever he wanted to play. [That was] one of my favorite things ever. We wouldn’t even really talk about it. He might suggest a couple of acoustic songs, but generally, the acoustic set, he just did whatever he wanted, and he knew that I would follow him.

The electric set, other than starting with [“Subterranean”] and maybe whatever he had put on next, then it was just a suggestion. There were some bizarre songs that he came up with.

I was looking up some statistics from your run. You played 243 concerts with him, and during that time, you play 215 different songs. That averages out to almost one new song per show, for your entire two and a half years, which is an impressive statistic. You’d think eventually you’d settle into some repertoire of 40 or 50 songs you’d rotate through.

I would say that that number, I guess somebody really went and figured it out, but that seems to me to even be a little bit pessimistic. I think there was probably more songs because sometimes he would do songs that I never knew what they were.

Even while you were playing ‘em?

Even while I’m playing ‘em. It wasn’t a song I had ever heard before.

He’s playing a song, you literally don’t know what the song is the whole way through—how are you able to play it?

Pay attention. [laughs] You really gotta listen. Like I said, myself and Tony Garnier and Larry Campbell and any other of these people you want to talk about, we started playing when we were kids. I’ve been playing in bars since I was 11. I learned probably several thousand songs in that time. There’s only 11 notes, and really, within the structure of most songs, there’s only seven notes. There’s do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, and do at the beginning. Every song almost is built on seven notes in the Western canon.

He’s not doing microtonal scales.

Yeah. If you go to Cambodia, India, all bets are off. There’s a lot more notes. But we only got seven notes in 99.99% of the songs. So once the song starts and you hear the melody and you see the chord structure, you know where it’s going to go. That’s just experience. That’s just years and years and years and years of experience.

Bob, he’s this musicologist. He knows all these songs. If I asked him things about the traditional stuff, he would take the time to sit and tell me. “Buffalo Skinners” [aka “Trail of the Buffalo”], he started playing that at some point. Oh, man, what a song. He sat down and he told me about where it came from. There’s a million verses in that song. He sat there and told me all the verses that he knew. I have this little book that I used to write out lyrics and stuff. He even said, “If you run into Ramblin’ Jack, ask him. He knows more verses.”

I started doing that song. I do it all the time. I do it now as kind of a North African groove, with Josh Dion, the great drummer. You know that band Tinariwen? We actually do it with one of their grooves, but we do “Buffalo Skinners.”

I couldn’t find a recording of that arrangement, but here’s an acoustic one from a few years ago:

I’m really grateful to Bob that he did that. He didn’t have to take the time to teach me those songs and talk about that stuff. A couple times, he would have me come on his bus. We had three buses: Bob had a bus, the band had a bus, and the crew had a bus. I’d always ride on the band bus. One night, we’re coming off stage at the Indiana State Fair, and he puts his hand on my shoulder as we’re all headed for the bus. He goes, “Hey, ride with me tonight.” I’m like, “Whoa, okay.”

We still had cassettes back then, and on the bus he’s playing these cassette tapes of all this great old traditional stuff, because by then he knew I was really into it. He said, “This is a good song, you should learn this one.” “And this one, see how this turned into this, and then Hank Williams wrote--” You know, he totally knows the history of all that music in the United States. He knows all those songs. Just off the top of his head. He can play hundreds of these great traditional songs. It’s amazing.

Some of the best parts of the tapes I’ve heard of your shows are those traditional songs. “The Water Is Wide,” “Barbara Allen,” “Eileen Aroon.” I’ve never heard of any of these songs before listening to some of these tapes.

I used to love playing “Eileen Aroon.” It was a great Irish song, which he learned I think from the Clancy Brothers. He was friends with them going way back. Great lyrics in that song: “There is a valley fair, castles are sacked in war, chieftains scattered far, truth is a fixed star. Eileen Aroon.” Come on! Those are some lyrics, man. “Chieftains scattered far.”

I was listening to a show the other day where he does “Dark as a Dungeon.” I think you’re singing a little bit. Did you do backing vocals often? Did you have a mic set up every night?

Probably because I knew that song. It’s by Merle Travis. I did have a mic, yes. Although we never, ever talked about it, he didn’t mind if you came up and sang some backing vocals. He never told me not to do it. I wouldn’t do it all the time, but occasionally I would, and he never said anything about it. He didn’t say much about anything—”do this” or “do that.” I just assumed he was pleased with what was happening at the time.

We’ve been talking about the great covers. Were there any of his own songs that were particular favorites for you to play?

“Tangled Up in Blue” is just such a great song to play. “Maggie’s Farm” was always fun because I got to do my Mike Bloomfield thing on it, shamelessly copying him. I made up this little lick at the beginning that I would play on the low strings and get the groove going.

You often opened with “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” which was shockingly the first time he’d ever played that song.

Really? Wow. I love that song. We’d do a The Clash version. Really fast. As fast as you can play it. [Recites the opening verse at top speed]. Just rip through it.

That’s one thing I love about listening to these tapes. Acoustic sets aside, in terms of the full-band electric, they are kind of garage rock, punk. I think that’s something fairly unique about this lineup in these first few years of the Never Ending Tour, that energy level.

That’s kinda what he wanted, I think. He just wanted to rock. He wanted to play.

I mean, you could never tell with Bob. He didn’t let on if he was having fun. If you go all the way back to the '60s and listen to Bloomfield, Robbie and The Band, every once in a while—I think he even did it maybe on Highway 61—when the guitar player was playing the solo, Bob would make this sound like “yeeoow.” Off mic, but you hear it. I had heard it on tapes with Bloomfield. I was like “Aw man, I wish Bob would make that sound one time.” And one night he did. I was playing the solo and he made the sound. I was like, “Damn, that’s it. I’m happy now.” That was all I wanted.

What is your take on Bob Dylan as a guitar player?

When I would occasionally go on the bus with Bob or go in his hotel room or something on a day off, he’d be sitting there playing. And he’d be playing his ass off. I mean playing acoustic guitar, fingerpicking, super high quality. He can really play. I know that he’s had like carpal tunnel or whatever. He’s had troubles. His playing might be a little bit different than it used to be, but he could really, really play. And listen to stuff on especially the first six or eight records where he’s fingerpicking stuff. He’s a great, great guitar player.

Shortly after your era, he did those two folk albums, just him and an acoustic guitar.

Right. Yeah, he can really play.

I don’t think I ever got to play “Blind Willie McTell” with him. I always wanted him to play that song. I suggested it a few times, but he was like [growls]. We did get to play “Visions of Johanna” a couple times. He just went into it. No warning.

That’s a song I’m sure you recognized.

Yes, yes, we knew that one. When I got with him, I probably knew his first ten albums inside out. Every song. It would be great if he would do “Love Minus Zero” or “Takes a Lot to Laugh.” Or “Tambourine Man,” of course.

With “Tambourine Man,” we were in London. George Harrison is there, all these English pop stars, guitar players, famous, heavy-duty people are there. I was kind of freaked out that night. I’m like, “Wow, all these guys that I’ve studied and listened to, here they are.” We’re on stage and we’re playing “Tambourine Man.” And the way they would do the acoustic thing was Bob would of course be front and center. There was just one round spotlight. Bob was well-lit; you could see him. I’d be on the edge of that spotlight, lit up to about the middle of my chest so that you could see my hands and the guitar that I was playing, but you couldn’t really see my face.

We’re playing “Tambourine Man,” and he gets to that line about “Just to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free.” I started crying. I’m like, “I can’t believe I’m here playing this song with Bob, and George Harrison’s over here on the side of the stage watching.” Playing with him was a great moment, years, in my life. It was wonderful.

You’re there for two and a half-ish years. How did it change musically over that time for you?

It changed every day, because of the endless repertoire of songs he has in his head. And we traveled to interesting places. Sometimes we stayed in pretty funky places, because Bob liked those funky places. I like ‘em too, so I enjoyed it.

Like what?

I remember one time we were in Detroit, and it was in the summer. It was blazing hot, it had to be in the 90s, 95% humidity. We’re saying in on one of those old-time motels shaped like a horseshoe, all on one level. You pull your car right up to the door of your room. Remember what that’s like?

They always had names like the Thunderbird or something.

Right, the Thunderbird Motel, exactly. I’m walking along, and the door to one of the rooms is open. I hear somebody listening to a baseball game. It’s Bob. He’s sitting there watching the game. He doesn’t have the air conditioner on or anything. He’s got the door open. It’s 98 degrees. He says, “Hey, what are you doing?” So I went in and chatted with him for a while, watched the ballgame. Not everybody in the band loved that kind of travel experience, but I did. I thought it was great.

I had a great time playing with Bob. I wish that I could have always played with Bob. But I had too much going on between in the show [SNL] and my regular life and everything. It was just too much.

Chris told me that you and he were flying back and forth on Saturday nights to play SNL. You were doing both.

We were doing both. There were a lot of times when Bob would not take a gig on a Saturday night so that me and Chris could get back.

I was talking before about the Rolling Thunder documentary. At the end of it, they list every gig starting with [1975], and they have every tour, every day, every city. That was so great for me to watch because then I could remember, “Oh yeah, that place in Sweden was so cool.” That kind of stuff.

Is “that place in Sweden” a real example?

Yes! We played an amazing show in Sweden. It was an outdoor show in a place called Christinehofs. There was an old castle there. It was really cool.

With Bob, we got to play in some places that bands don’t usually go. I didn’t experience that with anybody else I’ve ever worked with except for Roger Waters. Roger Waters also goes places that nobody does. That was great with Bob. We got to go to some different places.

Playing with the level of artists you play with, a lot of them would just be going from corporate arena to corporate arena. Fairly interchangeable.

There’s a lot of that. Where, with Bob, you never know. You’ll do the arenas, and then the next show will be in a field in some little town in Italy. That one, I can’t remember the name of the town, but we pull in in the buses at 1:00, 2:00 in the afternoon, and there’s nothing there. An empty field. There’s no stage, there’s no fences, there’s nothing.

I remember the manager-type guys that were with us were like, “What is going on here?” They’re getting off the bus, they look around and finally, literally, an old guy with a wheelbarrow with some wood shows up with hammers. He’s going to make us a stage. He did make some platform, but we wound up pretty much on the same level as the audience, just on this flat, wooden thing in the grass. It was a great gig.

There’s this photo I love of you all playing at the Santa Barbara Bowl in the daytime, and there’s local kids just sitting on a wall behind you.

I’m pretty sure that Tom and the Heartbreakers came to that show, because it was near where they lived.

Was the term “Never Ending Tour” ever used back then? When did you first hear it?

I’ve never heard Bob say that, but I saw it written back then. Bob likes to play. He likes to be out there playing. I always, in my mind—and I probably even told Bob this, I said, “You just want to be like Ernest Tubb, man. You just want to keep working, keep doing those shows.” That’s how it felt to me.

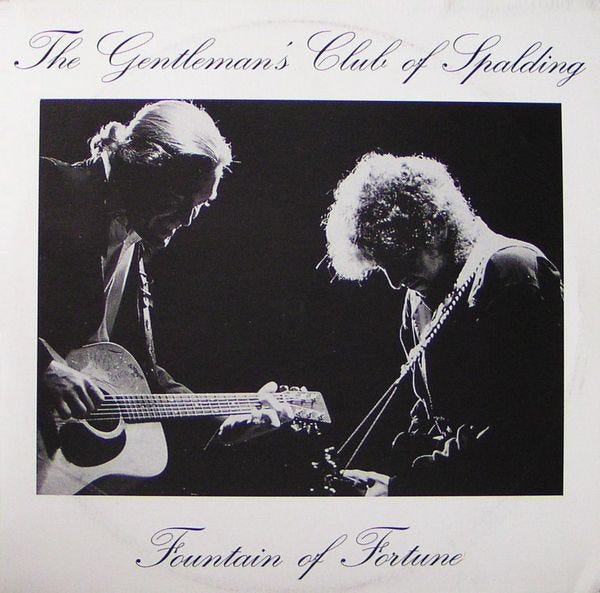

In the World Gone Wrong liner notes a few years later, he wrote, “There was a Never Ending Tour but it ended in '91 with the departure of guitarist G.E. Smith.”

Did he say that? Ha.

There’s a bootleg LP from England called The Gentleman[’s Club] of Spalding. The guy who printed it up and was selling them gave me one back then. On the cover was a really nice picture of me and Bob with the acoustic guitars leaning in towards each other with our heads almost touching. When I was leaving, I asked Bob if he would sign it for me. He wrote me a really nice note. He didn’t say “Never Ending Tour” but he wrote something kinda like that.

I just loved playing with him, I really did. I don’t think about it all the time, but now this morning I’m thinking about it, I’m like, “Yeah, I really enjoyed that.”

Why did you leave? Was the thing with SNL just too exhausting?

No, it wasn’t exhausting. It was complex. There was so much going on. I got married, the SNL thing, Lorne was leaning on me to stay and do that. Sometimes I wish I just stayed with Bob, but who knows? It is what it is.

How long did you stay with SNL after?

I was there for 10 years, from '85 to '95.

In your last few months with Dylan, there’s a variety of other guitarists sitting in every night, sort of auditioning live on stage. What’s the story behind that?

I gave them plenty of notice; I didn’t just walk off. There was no bitterness or anything. I just said, “I gotta leave. I gotta go back to New York.” We had different people sit in. The one I remember the most is Stephen Bruton. Texas guitar player, who unfortunately then passed away. Great guy. He sat in with us, in my memory, somewhere up in the Pacific Northwest, like in Portland.

It was one of the best gigs I’ve ever played anywhere. Me and Stephen, it was magic between us. We really tore it up that night. Bob got into it, too. He was having fun. He knows a good band when he hears it. Some nights, it’s just like that. You never know when it’s going to be.

Did you have rehearsals with all these guys?

No.

Just sitting in cold?

They would come to soundcheck.

Trial by fire.

Yeah. Why not?

Then, after all that, the guitar tech, César Diaz, takes over your post.

Yeah. [laughs] My old friend. I met César in 1969. He had come from San Juan, Puerto Rico, not long before that. He had a brother that was already up in the Bronx, Angel. He had come and stayed with his brother. Then César started hanging out in Greenwich Village. He met a girl who happened to be from Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, my hometown. So he followed her to Pennsylvania.

Now, César barely spoke English at this point. I’m driving down the street in Stroudsburg one day in 1969, and I see a guy carrying a Rickenbacker electric guitar. No case, just walking along with the guitar. I pull the car over and go, “Yo, who are you?” That’s how I met César. We were great friends until, sadly, he got sick and died.

Man, César was the greatest. He was self-taught on guitar, certainly. As far as taking care of guitars and amplifiers and stuff, he was a real genius at it. We’d be in the middle of the gig, and you’d look over and see he’d be throwing parts up in the air, he’d have the soldering iron out. He was great, and he was a really good guitar player. Me and César played together a lot.

Was Bob himself a guitar head, a gearhead? Did he care what type of guitar he was playing, or what amp he was using?

We had some conversations about guitars. I would ask him about guitars that he used to play. Like, “What ever happened to this one or that one?” '60s stuff, some of the really iconic ones.

A lot of times, guitar dealers would come to the shows to try to sell a guitar to me or Bob. He told me, “Keep an eye if you see an acoustic guitar that you think I might enjoy.” A couple of times I found something. I showed it to him and he bought it.

Me and César bought so much gear, the truck drivers started saying, “Listen, the trucks are full. Stop, stop! No more!” Because back then, this is before the internet and before eBay and everything, when you go down the middle of the country, there was tons. This stuff is supposed to be rare, they talk about these vintage guitars being rare—they made thousands and thousands of these things. Old Fender amps. We got so much stuff, it was insane.

You mean like once you’re out of New York or LA where everyone’s competing for the same vintage gear?

Yeah. Once you get off the coast, this stuff was free. Like I’ve always enjoyed playing lap steel. Even back then, a good Gibson or Fender lap steel might be $200, $250 in New York. When you go down the middle of the country, it was $50. $25.

I remember in Salt Lake City, I saw a big Fender Telecaster in the window of this pawn shop. I waited till the next day when they opened up again. I bought the Telecaster and there was a lap steel in there. I said, “How much is that?” They said, “I dunno, just take it.” The guy just gave it to me.

No kidding.

That stuff was worthless then. Now that you go on Reverb and eBay and they want $1,500 for them. They’re not worth $1,500, folks. They’re still worth $150.

You never played lap steel during your time with Dylan, right? I know Bucky Baxter came in shortly after and played it all the time.

No, I don’t think I did. Although, boy, we had plenty of them on the truck. I can’t imagine I never tried to play one. Probably not, because, other than Bob, I was the only guitar player. I had to drive the songs along to a certain extent.

While you were there, Dylan was not using his touring bands for records. You play a million shows with him, but are not on a Bob Dylan album. Was that a disappointment?

Well, sure, I would have loved to have been on one. In Bob’s book, he talks about that we’re in New Orleans, and me and him are sitting at a little table outside. He tells this story that we’re having tea. That’s really true.

New Orleans in August, this is another time it’s brutally hot and humid beyond belief. We’re right next to the Mississippi River. Me and Bob are sitting outside, man. We like it.

My sister lives in New Orleans. I’ve been there then. It’s rough.

You know it, man. It’s serious. But actually, I enjoy that and so does Bob. Anyway, we’re sitting outside. Then he was doing the record that Daniel Lanois was producing [Oh Mercy].

I was talking to Bob about, “Man, just let me come and play mandolin on something, just to get my name on one of your records.” He said, “I can’t, man. Daniel won’t let me.” Then Daniel comes walking up. I got up and left. Daniel just didn’t want another guitar player on there.

Bob Dylan’s description in Chronicles, Volume One:

“It was autumn in New Orleans and I was staying at the Marie Antoinette Hotel, sitting around by the pool in the courtyard with G. E. Smith, the guitar player in my band. I was waiting for the arrival of Daniel Lanois. The air was sticky humid. Branches of trees hung overhead near a wooden trellis that climbed a garden wall. Water lilies floated in the dark squared fountain and the stone floor was inlaid with swirling marble squares. We were sitting at a table near a small statue of Cleo with a clipped nose. The statue seemed to know we were there. The courtyard door swung back and Danny came in. G.E., who surveyed the world with a set of unblinking steel-blue eyes, looked up warily and met the gaze of Lanois with a glance. “See ya in a moment,” G.E. said, got up and left.”

To finish, let me just throw a couple of notable gigs at you. What do you remember about Toad’s Place, the famous four-hour marathon rehearsal show?

I had lived in that part of Connecticut all through the '70s, from '71 to '77. I played at Toad’s Place. I knew it when it was still called Hungry Charley’s. You walked in and there was a big glass jar with hot dogs in it. You’d get a free hot dog.

Whoever is naming that place is doing a great job. Those are both terrific names for a venue.

Right? Yeah, we went to Toad’s. As always, you go on stage and Bob starts calling songs, and we just kept doing songs. It went on and on. At some point, I’m looking at Tony, I’m going, “This is getting long, isn’t it?” He’s like, “Yeah. Just keep going.”

My biggest memory of that show, other than how long it was, was at some point during the show, Bob comes over to me and says, “Have you that Bruce Springsteen song, ‘Dancing in the Dark?” I said, “Yeah…” He goes, “Play it!” [laughs]

So I start playing it. I remember the lick. You know, the [sings the synth riff]. I’m playing the lick, and he’s singing it. We obviously didn’t know the whole song.

Dylan has covered many wild songs in his career, but I’m not sure any song ever—in terms of just, you can’t believe he’s singing this song—tops “Dancing In the Dark” at Toad’s Place.

[One night, during] the electric part of the show, the lights go down. I walk over to him, and he goes, “You know ‘Moon River’?” I went, “Yeah?” He goes, [Dylan voice:] “In C! Ah mooooon…” He just started singing it. I started playing it. Tony was looking at me like, “Oh, my God.” But Tony’s a heavy jazz player, so he knows those songs. We got through it. That was the one that really got me. “In C!”

I know that one. He dedicates the song to Stevie Ray Vaughan, who had just passed.

That’s right. That gig, where Stevie died, is up in Wisconsin. We played there the night after. We were the next show.

Another show I really like, an interesting one-off, the Bridge School, end of 1988. Just the two of you doing a six-song acoustic set. Do you remember anything about that show?

I think we started with “San Francisco Bay Blues,” the old Jesse Fuller song. [sings:] “Walking with my baby down by the San Francisco Bay.” Again, I knew that song. Little children in the street know that song. Bob didn’t have to tell me anything.

I loved being there because Neil on that show. Petty was there. It was great to see those people because I had gotten to know them a little bit.

Jerry Garcia was on that bill too.

One thing that happened, it must have been at that show, in the afternoon we’re backstage, and there was a big round table. Sitting around the table was Bob, Jerry, myself, and somebody else. Bob and Jerry are taking turns just playing songs, trying to stump each other in a way, with like the most obscure, traditional folk ballad. This is a game that they must have played from way back.

Then I remember Jerry showing me, not as part of the competition, the way he did “Friend of the Devil.” Because by then, he’d had that heart attack or stroke or something [it was a diabetic coma in 1986].

He had this tremor in his left hand that never went away. But he used it when he played guitar. It was like this really slow vibrato. So he played “Friend of the Devil” real slow with that vibrato. He showed me how he did it. He was like a little kid. “Isn’t that cool?” I was like, “Yeah, that is fucking cool.”

But him and Bob going back and forth with those songs was great. At some point, both Tom and Neil came in and were standing there watching. They were amazed, too, at what was going on. I think Tom even sat down and played a little. I don’t think Neil did. Anyway, for me, to be sitting there with my guitar playing along was nuts.

Then we saw everybody again a few years later at the Madison Square Garden show. That’s the last thing I did with him, I think.

It’s actually not. You sat in twice with Dylan after that, one show at the Beacon in ‘95 and one show in Ann Arbor in 2000.

Really?

Yeah. I don’t know what you were doing in Ann Arbor.

It must have been at that blues festival. I was out there with Hubert Sumlin and some other guys. I guess Bob was in town a night before or something like that. I sat in, but that’s not a real thing. That’s just for fun.

So let’s talk 30th anniversary, “Bobfest,” a couple of years after you’ve left. How did you get that gig? What was your exact job?

Music Director, which is a gig I do. That’s what I did on the TV show, and I’ve done that with a lot of other bands.

We had stayed in touch, even in that period between whenever I finished touring with Bob and that thing. Every once in a while, I’m not talking every week or every month or anything, but every now and again, Bob would call me, and say hello.

Fishing for you to rejoin or just a social call?

No, no, no. Just to say, “Hey, what are you doing?” Very short. I remember he called when I was home at Christmas in Pennsylvania with my parents. My mother answered the phone, and she goes, “George, it’s Bob.” She didn’t know which Bob. Just some guy named Bob.

Anyway, Jeff Kramer, who was then Bob’s manager, called me and explained what they were going to do and gave me this list of most of the people that were going to be on it and phone numbers. I was supposed to call them up and see which Bob Dylan song they wanted to play. Fortunately, by then I knew most of the people, but I had never met Johnny Cash. I’m supposed to call up Johnny Cash?

Just cold-call him.

Yeah. Call up Johnny and ask him what Bob Dylan song he wants to do. And what if he wants to do one of the songs that somebody’s already got? I’m terrified. But it all worked out great, and everybody was so cool on that show.

I was amazed that nobody wanted to do “Like a Rolling Stone.” Who wound up doing that? I don’t even remember.

Mellencamp I think.

I think you’re right. I remember Lou Reed did “Foot of Pride,” not exactly the most well-known Bob song. Ron Wood did “Seven Days,” I think it’s called. Ron Wood was great, man; he tore it up.

But the one that everybody remembers is Johnny Winter doing “Highway 61.” We had rehearsed, and Johnny wanted it fast. “Play it fast.” And we were playing it fast. Keltner and Anton Fig were drumming. Duck Dunn was playing bass. Then at the show, if you see the film, Johnny keeps turning around to me, and he’s rolling his arm around, going, “Faster! Faster!”

I was talking to one of the crew guys who worked on it, and I didn’t even realize one of the backing singers is Sheryl Crow, before anyone knew who she was.

Yeah, Sheryl was on that. It was nuts because there were so many people on stage and so much going on, but it came off great. I have to say that everybody, especially the most famous ones—George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Petty, Neil—we had slotted in people two days before the show to rehearse with the band. These people are coming from all over the world.

Every single of those four people I just mentioned— I remember Clapton specifically going, “Oh, if Lou can’t come at one o’clock, give him my slot. I’ll come at 11.” Fucking Eric Clapton, he doesn’t have to do that. George Harrison, same thing, “Oh, give Tom my slot. I’ll do it whenever. We don’t even have to rehearse.”

No ego games, is what you’re saying.

No, no. It was great. George Harrison, when he showed up, had T-shirts made for the guys in the band that said “Bobfest,” and guitar picks for the guitar players. “Bobfest” and the date, “Madison Square Garden,” on the guitar picks.

Do you still have yours?

Don’t have the T-shirt. I never wore it, but I can’t find it. Somebody must have grabbed it. But I do have the pick.

One other famous show I wanted to hit on was the 1989 Beacon residency and the famous Bob Dylan exit at the end of the final show. What can you tell me about that?

Amazing. The way I remember this is that, before the show, I get called to come over to the dressing room. Bob and Jeff Kramer are there. Of course [Dylan’s longtime dresser] Suzie Pullen. Bob says, “At the end of the show, I’m going to play harmonica. No matter what I do, you guys keep playing. Watch Jeff on the side of the stage. Don’t stop until he tells you to stop.” Bob, like I said, didn’t give specific instructions, so this was a very specific “Something’s going to happen, and don’t fuck it up.”

So we get on, and I’m not even thinking about that. We were doing a little residency, so we had a nice groove going. We come up to the last song, whatever it was, and Bob’s playing harmonica. He walks down off the stage into the audience. I think, “Oh, he is going to walk the aisle. This is so cool.” He walked down the side aisle playing harmonica. There’s all these fire exit doors that open up right onto Broadway. He opens the door and goes outside. I look over at Jeff and Jeff’s going, “Keep playing, keep playing.”

So we keep playing, we keep playing, and the audience of course stays because we keep playing. See, this was the trick.

Letting him make his getaway in peace.

Yes, which we would do sometime. If Bob wanted to get to his bus, we would keep playing while he went out and got in his bus and departed. So we keep playing for a couple of minutes and then Kramer gives me the signal and we finish up. That was a great piece of stagecraft. You know, Bob is an old vaudeville guy.

We come to find out later that he just went out onto Broadway and hailed a cab and went wherever it was he was going.

Thanks to G.E. Smith! Keep tabs on what he’s up to at his website, Facebook, and Instagram.

Here’s a great collection of the many old folk tunes Dylan and Smith covered, curated by friend-of-the-newsletter Tim Edgeworth:

Do You Know Pretty Peggy O? - Folk Songs from Bob Dylan's Never Ending Tour 1988-1990

Absolute gold Ray! GE tells these amazing stories so casually, I love it! Nov 4th, 1989 they played Fisher Auditorium at my college, Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Hometown of Jimmy Stewart. I win the Bob Dylan campus scavenger hunt and scored two tix, front row center stage. They come out and open with Subterranean Homesick Blues, and tear it up. The whole show and experience of being so close while they played is something I’ll never forget. I remember so well when they did the acoustic numbers and GE was right there just barely outside the spotlight. It was incredible, couldn’t stop thinking about for weeks. And I still do all these years later. Keep up the great work and thanks!

This was nice! Thanks to both of you.