Fred Tackett Talks Three Years Playing Gospel Songs with Bob Dylan

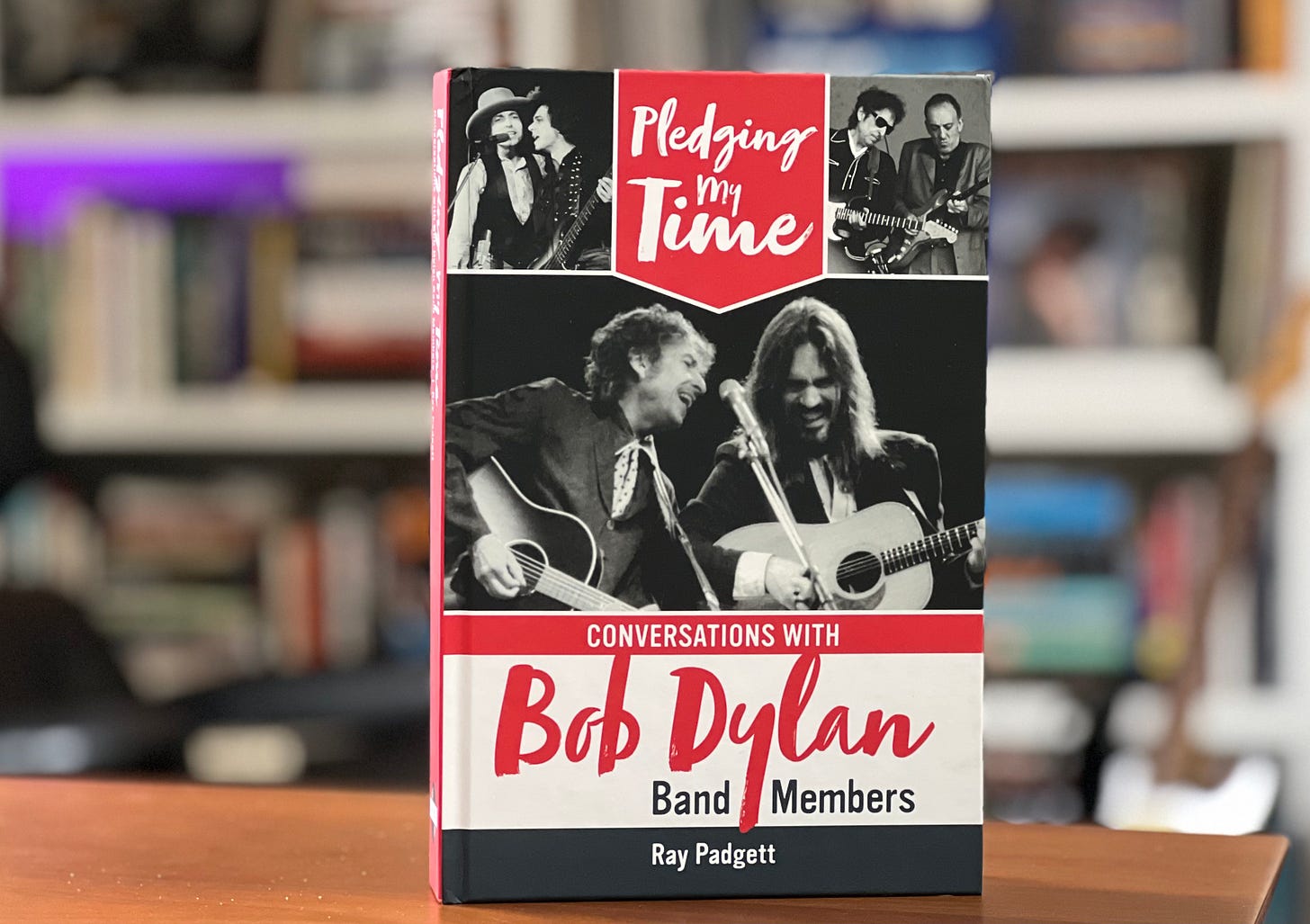

Happy first birthday 'Pledging My Time'!

Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members came out one year ago today! Thanks to everyone who’s bought it, said nice things, told their friends, etc.

It’s been quite a ride. The book was praised by Dylan-writer legends like Greil Marcus and Michael Gray, added to the official Bob Dylan Archives in Tulsa, and toasted by a bunch of dudes in a random Essex pub. My virtual book tour involved an event with the Bob Dylan Center and my Dylan Drummers Summit convening Jim Keltner, Stan Lynch, and Winston Watson in a Zoom. My IRL book tour took me all the way from Burlington, Vermont to Waterbury, Vermont (whew!).

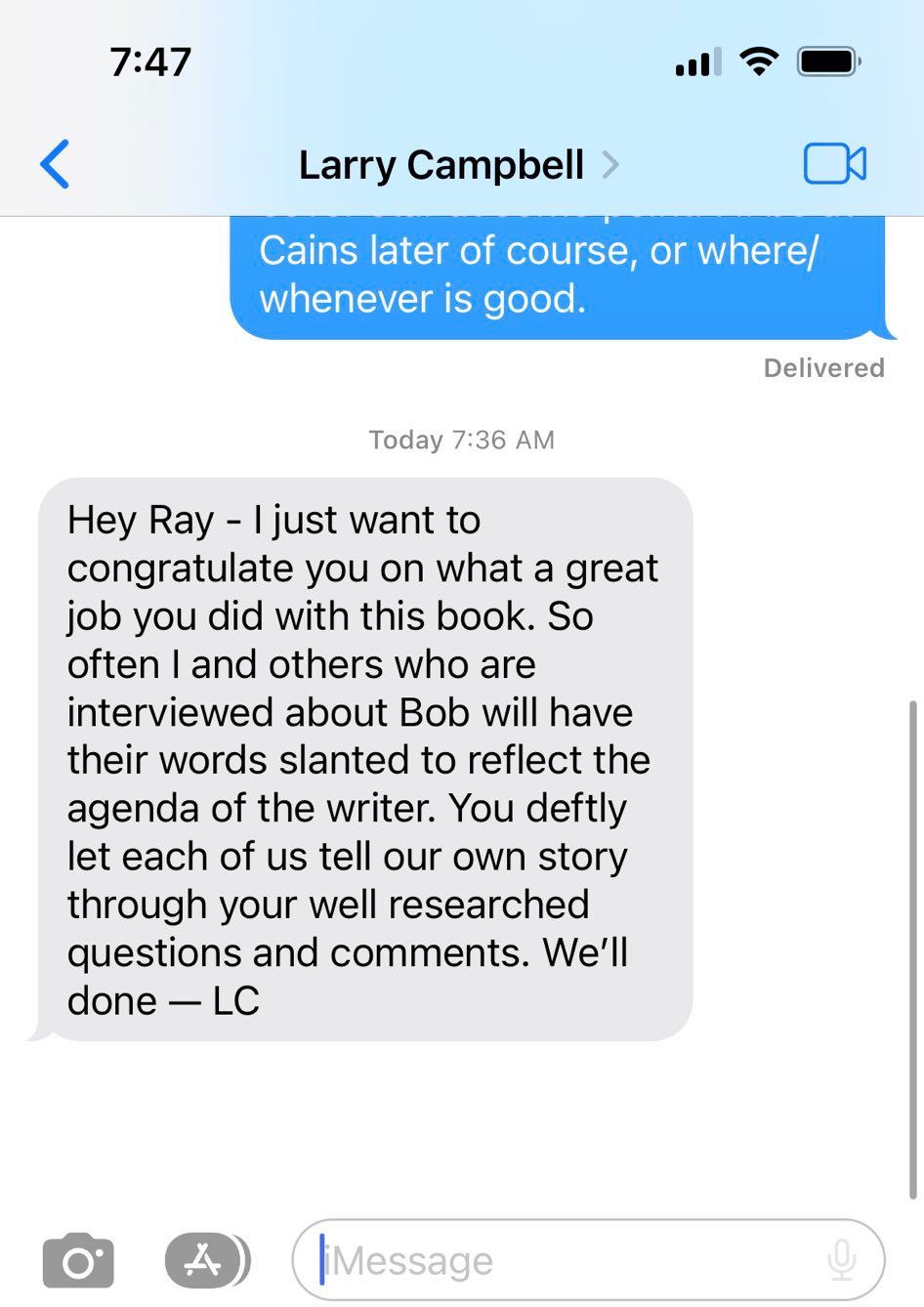

But nothing meant as much as seeing all my fellow Dylan superfans enjoying it. Or, rather, that was tied with what it meant to get responses like this from the musicians who, in many cases, hadn’t spoken in much depth about their time with Dylan before, but trusted me to share their story:

When I first published the book last summer, I figured that I’d run many of the interviews in the newsletter over the subsequent months. But, as it happens, I’ve conducted so many new interviews since then that I really haven’t. I’ve only posted Dickey Betts when he died, and half the Richard Thompson one for an anniversary. And I’ve currently got 14 still-to-be-published interviews sitting in the can right now, so I probably won’t excerpt many more book ones. If you want to read my conversations with Martin Carthy, Freddy Koella, Spooner Oldham, Jeff Bridges, Happy Traum, Duke Robillard, etc, better get at least one book upon your shelf.

But, for this special anniversary, I’m releasing one chapter from the printed page. Below is my conversation with gospel-era guitarist Fred Tackett. I know many of you will have already read it, but one nice thing about the online format is I can embed more video and photos. So at least scroll through for those.

Guitarist Fred Tackett is best known for his work with Little Feat. He worked with the band starting with their iconic third album, Dixie Chicken, and continued to collaborate with the band and frontman Lowell George until George’s death in 1979. When Little Feat reformed in 1988, Tackett became a full-time member, and he’s stayed there ever since. When we spoke on the phone, he was riding the Little Feat tour bus somewhere in the Midwest.

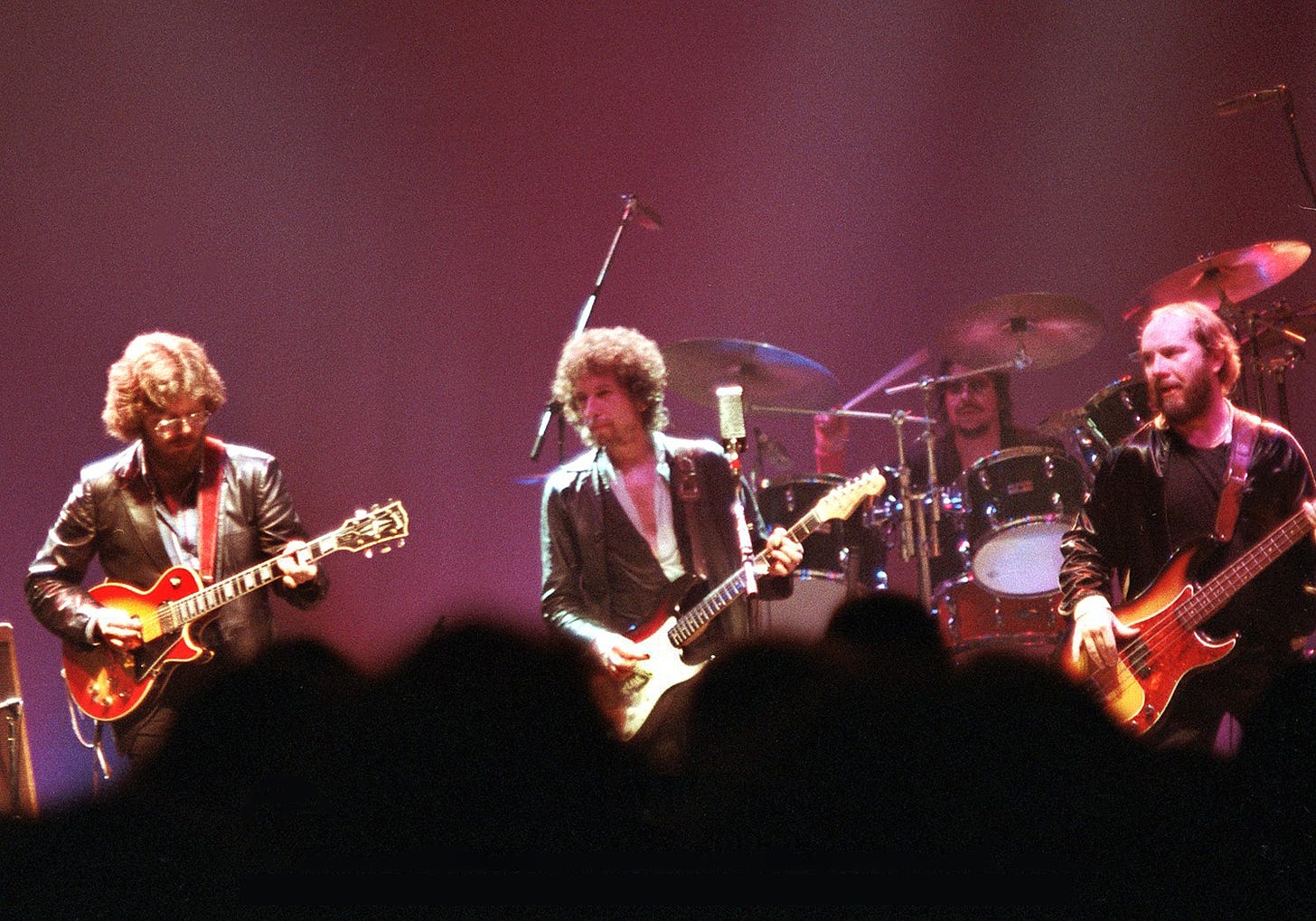

George’s sudden passing actually precipitated Tackett’s work with Dylan, when the guitarist unexpectedly found himself with free time right as Dylan was putting together his first gospel-era band. Tackett accompanied Dylan for every single show in those three years, from the first year in 1979 when the band was performing exclusively Dylan’s new Christian material through the end in 1981 when they were mixing oldies back into the sets. He also joined the touring band to record Saved and Shot of Love.

In recent decades, Tackett has found time in between his Little Feat duties to appear as a sideman on an absurdly long list of records by everyone from Dolly Parton to Bob Seger. He even recorded with Dylan’s son Jakob, on The Wallflowers’ quadruple-platinum 1996 album Bringing Down the Horse, making him one of the few musicians to collaborate with two generations of Dylans.

We’ll start with my usual first question. How did you get involved?

Well, I’d been on tour with Lowell George, and he died on that tour [June 29, 1979]. About two weeks after that, I think Jim Keltner and Tim Drummond basically recommended me as somebody to audition.

How did you know those guys?

Well, I’d worked with Timmy Drummond and Jim Keltner on sessions for billions of people over the years. I’d been seeing Drummond, so maybe he had something to do with it. My wife called me up at a session and said, “Hey, we got a call from Bob Dylan’s office. They want you to come down and jam with him.”

We did that every day for about three weeks. I was driving over every day to Santa Monica, going over mostly his brand-new songs. I remember I was driving down the road and I thought, “Wow, man, three weeks. I wonder when we’re going to get to the end of this.”

Was it clear that this is an audition? Or that there’s a tour?

No. It’s just like, “Want to come down and jam?” I kept thinking, “Well, heck, what is the point of all this?” I knew they were going to go out and do a gig or out on tour, ‘cause Spooner Oldham and all the band was there, but nobody was really saying much about it.

I mean, I was starting to get a little frustrated. Then I told myself on the way down there, “There’s 50,000 guitar players who would love to go spend three weeks jamming with Bob Dylan and Jim Keltner. What are you griping about?”

I think just a couple of days before we were getting ready to leave, Bob called me up on the phone and said, “We’re going to go do this Saturday Night Live show and then do a tour. Can you play with us?” I went, “Heck yeah, man. Sounds good to me. Have your manager call me and we’ll work it out.” He goes, “I don’t have a manager.”

After we did our little rehearsal the next day, he called me into the office he had. He said, “Well, what’s the deal?” I started to say, “Well, Bob—” and he held his finger up over his mouth, like, don’t talk so loud, and pointed to his ear. He leaned his head over, and I had to lean into his ear. I say, “You know, Bob, I’d normally get session work at double scale.” That’s like $600 a day or something like that. He leaned back and looked at me like, are you crazy? Then he’d stick his head down again like, talk to me some more. That was just hysterical. He was playing around with me with his great sense of humor. Anyway, it all worked out fine, and that’s how I got the job.

The first album Slow Train Coming, is that out at this point? Do you know those songs?

Yeah, we were getting ready to go tour behind those songs. Mark Knopfler [Slow Train guitarist] was doing his own thing. He wasn’t going to be on the gig, so they were looking for a guitar player.

Knopfler has such a distinctive sound. How do you find your own way into those songs?

Well, first thing I did was stop playing Stratocaster, which is what I normally would play, and start playing a Les Paul so that I would sound different. I knew I wasn’t going to compete with what Mark Knopfler was playing. He plays beautiful stuff on that record. I just started playing other stuff that I hoped was alternatively as beautiful. Kurt Vonnegut famously said for artists, if you leave home, you’re going to run into Mozart on the campus. Do your own thing and don’t worry about how many people are so much better than you, because you will run into Mozart.

Bob was playing a Les Paul as well. Finally, at one point, he said, “Hey, you know what, these things are too heavy. Let’s go back to the Stratocaster.” So we went back to playing Stratocasters again.

Did you have much of a background in gospel music? He’s got the backing singers, this big band. It’s not what people at the time associated with Dylan’s sound, much less lyrical content.

I was a trumpet major in college. So believe me, I played a lot of classic gospel music. I mean, I played trumpet in Jewish churches, Catholic churches, every kind of church. I played in brass choirs at Easter and all kinds of holiday stuff. Over the years, I did a lot of sacred music as opposed to secular music. Tent shows and revivals and masses and everything else. I used to work for J.T. Adams and his Men of Texas. J.T. Adams had a big Methodist Church in Sulphur Springs and he put on these giant tent shows. I played herald trumpet and had 30 pieces of silver in a bag I would shake in front of the mic. Just another gig, man. Just a different employer.

You mentioned Saturday Night Live. That’s a high-pressure first show.

It was! That was ridiculous. That was when I first saw Lou Marini, who I’d gone to college with in North Texas. He was playing in the Saturday Night Live band.

“Blue Lou!” He was in the Blues Brothers movie.

That’s right. He was like the best saxophone player in North Texas, him and Billy Harper. I got to reconnect up with him. Gilda Radner loaned us her dressing room so we could hang out there.

We just went out and did our thing, and it came off really good. I remember when we first started playing, I physically couldn’t look up. I thought, "I got to raise my head." I couldn’t do it because I was so nervous. I was like, stare at your left hand on the guitar and play and don’t look up. I just was paralyzed.

I was rewatching those videos, and you’re pretty prominent. You’re soloing on “Gotta Serve Somebody” and the camera’s on you—

That’s what it was like playing with Bob. You just jump into deep water and follow along. He wouldn’t tell you what he was going to play. I mean, on Saturday Night Live, we knew what we were going to do, but in a show, he’s liable to start playing anything. It was a great, great, great experience learning to be ready to do anything. Now, when I play with Little Feat, we do whatever. I don’t think about it and I don’t get nervous about it because of spending those three years playing with Bob.

Speaking of Little Feat, the first time I saw Dylan [in 2004], Richie Hayward was one of the two drummers.

Oh God, I totally had forgotten all about that. Richie was the best, man. Richie was like the Art Blakey of rock n’ roll. I mean, he just was one of a kind. Every drummer I’ve ever met worships Richie. And he was pretty much self-taught. That’s why he ended up having such a individual style. It used to drive Lowell crazy, because Lowell would go to great extents to get him to play a part, then Richie would immediately forget it. Next time he played the song, he’d play something totally different. Lowell would be, “I just spent two days getting you to play something, man!” Richie would be, “What are you talking about?”

After SNL, you guys have that long run in San Francisco, a dozen shows in a row.

I remember we were staying in the Tenderloin area. It was a funky area. Sitting in my room, I could look down and see the hookers on each corner. They had to keep moving, so when the light would change, they would go across. Walk and don’t walk, all day long. That’s where we were staying.

Was that by choice or was the tour on a tight budget?

I think it was by choice. Just where Bob said he wanted us to stay. I don’t even know if he was there. He probably was. He usually stayed the same place we were in.

The shows were great, because every night there was somebody coming to sit in. Carlos Santana was coming down just about every night hanging out. He was very supportive of the spiritualism of Bob’s music. He was going, “We’re doing the same thing. I have my version of this thing and Bob’s got his version.”

They opened that Dylan Center in Tulsa recently. One of the things they unearthed was footage of Michael Bloomfield with you guys. It was his last time playing with Bob and maybe his last time playing, period.

I think period. I did a bunch of interviews for that about Steve Ripley, who was also playing guitar with us later on. For the first couple of years, it was a smaller band, but then Ripley came in. He was very instrumental in getting that Tulsa museum going, because he lived in Tulsa.

Early on in the run, is there controversy? You hear about people wanting to hear the old hits and Bob’s not playing them. Instead he’s preaching.

There were occasions where Bob would turn the lights on because people were heckling and yelling things. Mostly like, “Play your old songs.” The very best comment that I ever saw was a guy in the front row had a poster board. Written on the poster board was, “Jesus loves your old songs.” I thought, “Great point.”

That’s clever. I’m sure it didn’t work.

No, but it was like, yeah, right on.

He had some funny stories. There’s some live tapes where he’s talking to the audience. He’s saying things like, “I went and played at this place and I tried to tell them about Jesus. It was weird, they’re making this sound, they’re going boo.” Like he’d never heard anything like that before. “I don’t know what that meant, man. Very weird.” That was hysterical.

Speaking of “Jesus loves your old songs,” halfway through he does bring back in older stuff. Did you enjoy doing some of the classics?

Oh yeah. I just had shivers that went up down my spine when we started playing “Like A Rolling Stone.” When people heard him starting that, the place went nuts. It was this epiphany that happened with the audience and the bands and everybody. I had chills.

Is there a whole other batch of rehearsals? You’ve got the gospel stuff down and now all of a sudden he’s adding 15 or 20 songs.

We went to rehearsal one day and started playing old songs. [He] didn’t have an explanation for it, saying, “Okay, we’re going to start doing this now.” We just started playing old songs again.

We went to San Francisco again a year later and did another residency thing there. Roger McGuinn came down and played, Rick Danko, Maria Muldaur, all kinds of people. I can picture Bloomfield sitting backstage watching television.

Jerry Garcia sat in also at that second run at the Warfield.

That was a funny night. Bob called him out on the second song that we played. Jerry told us later that he was high, man. He was noodling up in the upper register of the guitar, like all the time. When Bob was singing, he’s playing doodle-doodle-ooo, noodling around and doing all kinds of stuff. Bob’s looking over at me like, “What the fuck is going on?”

We got off the set and got in the van. Bob’s going, “That’s it, I’m not having people sit in with us anymore.” I said, “Bob, you gotta bring ‘em on the encore. You can’t bring someone on out the second song, because they’re going to stay there all night.”

I think this predates that a little bit, but you guys had that big performance with the Grammys where everyone’s dressed to the nines. What do you remember about that?

That was a fun time, man. I had a bowtie. Bob said, “Your bowtie’s too big.” I had to put on a smaller one. He had one of those clip-on kind of things. I had a more flamboyant and bigger one.

The Doobie Brothers were there. That was the night that they won all kinds of awards. They were friends of ours, so we were hanging with them. Tom Dowd was there in the audience. Rickie Lee Jones — I think she won a Grammy [Best New Artist]. A lot of people that I had worked for, and a lot of albums I played on were being represented. And Bob won!

That always helps. Did you have any favorite songs to play during your time?

Some of the ballads were my favorites. The one that Sinéad O’Connor did, “I Believe in You.” That’s a gorgeous song. Oh God, he had a couple of them that were just beautiful, beautiful, beautiful. I think “Man Gave Names to All the Animals” was probably my least favorite one, but I liked it fine.

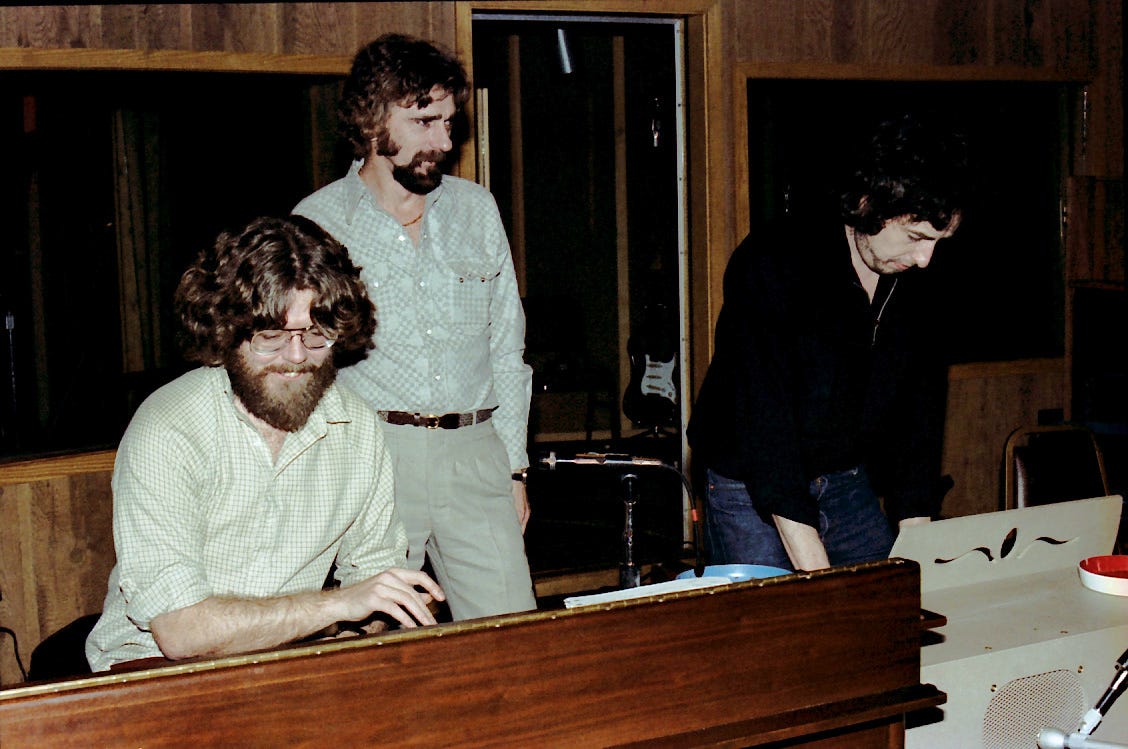

What do you remember about going down to Muscle Shoals to record Saved?

[Producer Jerry] Wexler said it was like the old Ray Charles band, because we were just on the road. We drove the bus into Muscle Shoals, checked into our Holiday Inn, went down to the studio, recorded for about five days, then got back on the bus and went to the next gig. Bob said, “Mix it and send it to me.” It was old-school.

Were you able to do it so quick because you’d been playing them live?

Yeah. When we were rehearsing for about three weeks before I got the gig, we were rehearsing all the songs off that were going to be on Saved. Bob taught us all the new songs.

How does he teach you a song?

He’d just play it on the guitar, start singing and we’d follow along. They’re not really complicated musically. You could hear what he was doing. There was never any charts or anything.

Later on, he had a cool way of rehearsing. I would go in early, and he’d say, “Teach the band a song.” He would give me a tape that was not one of his songs. We did Bob Seger’s “Night Moves.” We did The Muppets’ “Rainbow Connection.”

No kidding.

Yeah. Bob sang the shit out of that. My theory was, he didn’t want us to play his songs over and over. I think he didn’t want us to get parts, because if you play something four, five, six times, pretty soon you’ve got yourself this little part and you’re going to start to play it all the time. He was trying to keep a little more spontaneity in the band by not having us just beat his songs to death. He’d have us play “Rainbow Connection,” or that Neil Diamond song, “Sweet Caroline.”

That one they released on the Springtime in New York Bootleg Series in 2021. It is wild. I don’t think that’s something that had ever been bootlegged.

Jim Keltner and I later did a session with Neil Diamond and Burt Bacharach and Carole Bayer Sager, the songwriters. We’re standing around sharing a jay. Neil says, “The other day I got this tape from Bob Dylan. He sent me a copy of him singing ‘Sweet Caroline’. It’s great, but I was really surprised to get it in the mail.” Keltner and I both said, “We played on it, man.”

We did a good version of “Willin’” [by Little Feat] too. He said, “You got to sing harmony with me.” He was a good friend of Lowell’s. If you ever saw the back of Lowell’s solo album, he’s standing there with a rod and a reel and a bunch of seaweed on the end of the hook. Holding it up like it’s a specimen fish. That was shot at Bob’s house out in Malibu. Bob wanted him to play in the band, but he didn’t live that long.

So that’s Saved, and then you record Shot of Love. A lot of the same cast of characters, but a different location.

We did all those sessions at different studios in Los Angeles. One of my best memories is, Bob had a song called “Caribbean Wind.” Jimmy Iovine was producing. He called up and said, “Come down early. I want to get a track of this song before Bob shows up to play it to him.”

We were all down in the studio. Shelly Yakus was the engineer, Jimmy Iovine’s producing, and I’m in a back room with David Mansfield. I’m playing mandolin, and he’s playing fiddle. Jim Keltner was baffled off in a corner somewhere. We came in and listened. It was like the A-team studio sound, like all the other sessions that I would’ve done. A perfect pop-record sound.

We’re over at Studio 55, which was Richard Perry’s studio. It was an old studio that had been renovated. Richard Perry had made it the top notch. It’s where he did the Nilsson Schmilsson album and all that kind of stuff. So Bob comes into the studio, and they know that Bob really likes old vintage studios. He’s always looking for old mics and the old stuff.

They start telling him that Bing Crosby recorded “White Christmas” here in the studio. Bob’s like, “Yeah?” Then they play the track of us doing “Caribbean Wind.” Bob turns to one of his gofer guys and says, “Go get me the music for ‘White Christmas,’ because I can’t record any of my music here.”

Then he goes, “Fred, where are you?” I said, “I’m in the back room here with the mandolin.” He goes, “Get your electric guitar and come out here in the room.” They got rid of all the baffles around Keltner, and we just all started playing live. We’re going through “Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar” and different songs like that.

I look up in the studio, and there’s nobody there. Jimmy Iovine and Shelly Yakus just left. The only guy there was the second engineer who was running the tape machine, which was all we really needed, I guess.

Couple specific shows I wanted to ask you about that might be memorable. There’s this famous run at Earls Court in London in 1981.

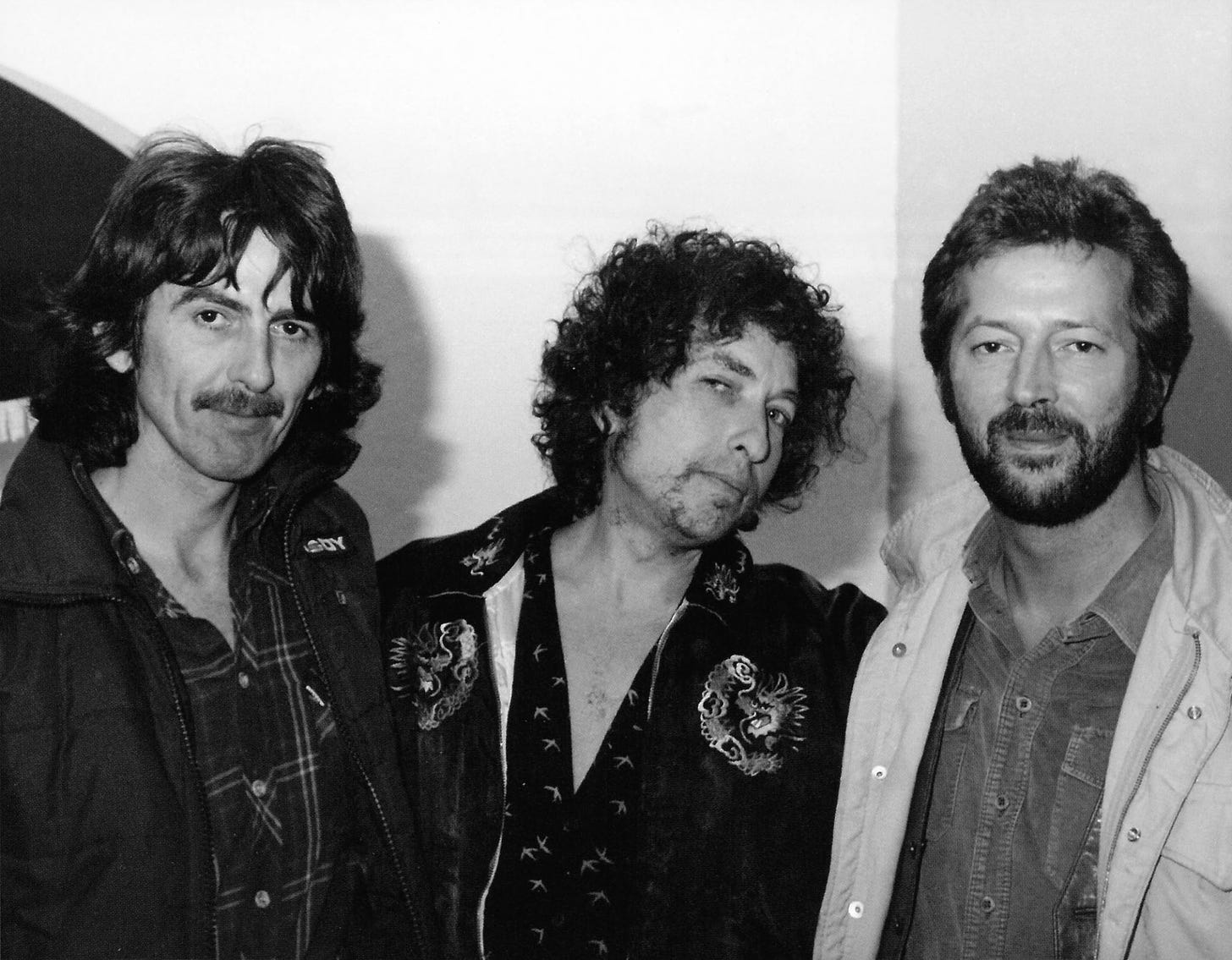

We stayed there several days. Stevie Wonder came to the shows. Eric Clapton was hanging out with us. I had this black beautiful electric 12-string that I would play on “Like a Rolling Stone” and different songs. Clapton came back and said, “Man, George Harrison and I are both out trying to figure out, what’s that guitar you’ve got there, man?” They were all lusting after it.

We went over to [percussionist] Ray Cooper’s] house. It was right after John Lennon had been assassinated. Julian [Lennon] was hanging out. All the guys were keeping close to Julian during that period.

Then a few weeks later, there’s a show in France where there’s a blackout and a tragedy.

At stadium shows in France, people would climb up the telephone poles outside. One guy would climb up and then people would start climbing up behind him, trying to see over the edge of the stadium. So people from the bottom were pushing the people on the top up. Finally, some guy hit the live wire on the top. That blew the whole stadium out, and the guy died. They caught one guy trying to cut the power underneath the stadium with a bolt cutter on a different occasion.

Here’s a real weird one. Dylan’s childhood friend Larry Kegan came out for a few shows to sing. Mostly notable because Dylan played saxophone, which I think is the only time ever. I’m pretty sure he doesn’t know how to play the saxophone.

I bet he thought he looked cool. He would walk around backstage with the strap of the sax hanging down. It looked cool, like you’re a bebopper. He was just kind of sporting it a little bit, and then he brought it on stage and played a couple notes on it.

You opened almost all the gospel shows with “Gotta Serve Somebody.” That’s probably still the best-known song of that whole set.

That’s a great tune, man. My musical brother Sam Clayton just has discovered that, and he plays it every day. It’s just so funky, man. Tim Drummond just has the simplest bass part, it’s just boom, boom, boom. It’s perfect. Great blues.

How about one of the best vocal performances, “When He Returns”?

“When He Returns,” that is just a beautiful song, man. Beautiful. He just sang the heck out of it.

What was really amazing about it was he used to play this harmonica thing at the end [I suspect here Tackett means “What Can I Do for You,” as his description matches that song more—RP]. This extended version. It was just him and Spooner, and Spooner would feed him these chords and Bob would just keep playing the harmonica. Spooner kept putting what we call substitution chords underneath it. The chords Spooner was playing just made Bob’s— even though he was playing the same notes over and over, every time he would play it, it would be sound completely different, because Spooner would put this other chord change underneath him. It was just gorgeous.

When they did the box set of Trouble in Mind, I asked the guy, I said, “Man, did you get that cadenza thing that Spooner and Bob would do?” They found the absolute best one man and put it on that box set. That was just absolutely transcendent.

Another song I always liked that never made an album or anything is “Ain’t Gonna Go to Hell for Anybody.”

That was one of my favorites too. It was funny. “I can manipulate people just like anybody, wine ‘em and dine ‘em…”

How about “Slow Train,” the almost title track of Slow Train Coming?

That’s just a classic tune. They’re all fun to play. He gave lots of room for improvisation. Sometimes I’d play two or three solos in a song. Then Spooner would play, and the piano player [Terry Young]; everybody had lots of room to jam doing all those tunes.

I guess my last question is, how does it end? You do this last US tour in ‘81, then is there talk of more?

I had an absolute feeling that this was the end of this particular bunch. He has kept, I guess, this latest band he’s had for years and years and years. Back in those days, his bands, you didn’t expect them to be lasting that long. The next record would come along and he would hire whoever to work with him.

Towards the end of the tour, down in Florida, I just had feelings. Every time I’d play a guitar lick or Jim Keltner would play a drum fill, Bob would do this whiplash and look around at you like, “What did you just play?”

You mean he was getting grumpy about it?

Yeah, he was like, “What did you just play?” Like he was shocked. Jim Keltner would play a drum fill, and he’d turn around and look like, “What was that? That came out of nowhere.” Just a normal drum fill. I started noticing that everybody was standing back as far away as they could get. I thought, “Well, this is pretty much I think the end of this.”

In fact, I told him after our last show of that tour in Florida, I said, “Man, it’s been a great honor playing with you, man.” ‘Cause I didn’t think we were going to be doing that anymore. And we weren’t.

Did the offstage vibe sour a little bit too?

No, no. Just musical. I just think that he was ready to do something else, ready to hear somebody else. It’s perfectly normal. Because it isn’t a band; it’s Bob Dylan. Little Feat is a band. You don’t think about changing the instrumentation that much. But with an individual solo artist, you expect the band to be a fluid operation. There’s no guarantee that this guy’s going to hire you for the rest of your life. You just expect things to come to a natural musical ending, which is what basically happened. We had done it for a long time. Time to go do something else.

Thanks Fred! Little Feat is back on tour this summer supporting their new album ‘Sam’s Place’. Check out dates at littlefeat.net.

If you haven’t bought the book yet, maybe one of these people will convince you. And, if you’ve already got a copy for yourself, it makes a great present for anyone who wants to know way too much about the time Dylan met The Pope or why playing with him is like jazz.

“Ray Padgett is the ideal interviewer—he really knows his stuff, so he can draw the best out of every musician he talks to. This is a tremendous collection of acute, revealing, often funny stories from those who’ve played on stage with Bob Dylan.”

— Michael Gray, author of Song and Dance Man: The Art of Bob Dylan“There already is an endless supply of books about Bob Dylan in the world. What could possibly be written now that seems fresh, much less indispensable? Enter Ray Padgett, one of the great modern Dylanologists, who has done the Lord’s work of tracking down Bob’s many collaborators over the years and getting the inside story. The result is insightful, fascinating, hilarious, illuminating, and, yes, indispensable.”

— Steven Hyden, author of six books including Long Road and Twilight Of The Gods, and the co-host of the Bob Dylan podcast Never Ending Stories“These talks open up like running streams. There seems to be no guile, no self-promotion, no agendas: maybe because Ray Padgett doesn’t either. There’s less I Was There than ‘and then I wasn’t’—and more fine stories than you can count. I love Louis Kemp on negotiating with Walter Yetnikoff—even if he does have a 13-year-old Bob Dylan singing Jerry Lee Lewis and Chubby Checker in 1954.”

— Greil Marcus, author of Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs“Padgett brings plenty of substance to make Dylan comprehensible. An active, close listener, he knows many things that his interview subjects have forgotten, so he can prod recollections.”

— Wayne Robins, veteran music journalist and writer of the Critical Conditions Substack“Ray Padgett's Dylan scholarship combines obvious enthusiasm, deep knowledge, broad understanding, and an abiding need to get things right. This is essential work both now and for the future.”

— Caryn Rose, author of Why Patti Smith Matters“This book is special. After countless books devoted to Dylan's lyrics, this one aims to unlock the magic of his performances by going straight to the source and talking to the musicians that helped create those moments onstage. Ray asks all the right questions, and the answers are interesting, entertaining, and often illuminating. An indispensable read!”

— Laura Tenschert, host of the Definitely Dylan podcast“If you're like me, you've waited your entire adult life for this book. Padgett digs deep and shines a spotlight on the people standing (and sitting) behind the man behind the shades.”

— Jon Wurster, writer/performer/drummer (Mountain Goats, Bob Mould, Superchunk)

Thanks for posting. I love reading these…I should really get the book. Thanks so much!

Congratulations on the anniversary, Ray. Your skillful questions elicited valuable answers. The wide range of characters filled in important gaps in history, and deepened understanding of what might have been known. It’s a most valuable resource for those of us who occasionally write about Planet Dylan.