Director Michael Borofsky Talks Filming Bob Dylan in the '90s

Supper Club, "Not Dark Yet," No Direction Home, a lost "Love Sick" video and more

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

For much of the 1990s, Michael Borofsky was Bob Dylan’s go-to director. He filmed Dylan on stage: the famous Supper Club shows, a bunch of the Never Ending Tour, advising on MTV Unplugged and Woodstock ‘94. He filmed music videos: the Time Out of Mind duo of “Not Dark Yet” and a never-seen “Love Sick.” He even did a lot of the initial interview filming for No Direction Home before Martin Scorsese entered the picture.

Much of that work is footage long beloved by Dylan fans. But some has never been seen, notably most of the Supper Club shows and the “Love Sick” music video (which involved a staged fight between Bob and Tony Garnier). Borofsky recently took time to walk me through all his work for Dylan, both the videos we can see for ourselves and the ones that remain locked in the vaults. Since it’s a longer interview, I’ve split our conversation up roughly by project, but the organization is fairly loose.

SUPPER CLUB

How did you first get involved working with Dylan?

I got brought into the Dylan world after the 30th Anniversary concert at Madison Square Garden. That had been shot already. VH1 or somebody wanted to do something, and [Dylan manager Jeff] Rosen came to me and said, “I need a package.” We spent a lot of time together doing that, because that was a very complicated show with all the people that contributed to it.

You mean, take this hours-long show and condense it into something shorter?

Yes. At the time, I was known as the video profile guy. Me and Rosen, we sat in a small edit room and spent days together trying to put a 22-and-a-half-minute show. 22:30 is what the cable networks needed for a 30-minute show. That's where it started. I was head of production at Sony as vice president of video and film. It really wasn't my job to do that, but we had fun sitting there and editing.

You have to remember, at that time, the 30th Anniversary show was a sort of a resurrection of Bob. Bob wasn't exactly burning the fire. A lot of music critics and longtime fans were saying he was mumbling lyrics in his concerts.

Supper Club is end of '93. How does that swim into the picture?

The Supper Club came out of that thing that I did on the 30th Anniversary show. What happened is [co-manager Jeff] Kramer and Rosen and Bob came up with this idea that it was time to relaunch Bob. Go back to his roots. Intimacy was the idea. We couldn't find a good venue on Bleeker because of sightlines for the cameras, so they came up with this scheme at the Supper Club, which was, “Let's put Bob out there. Have him do his stuff, and we'll get past the ‘Mr. Mumbles’ chatter.”

The idea was to get him into some kind of back-to-the-past sort of thing. We can't put him at the Cafe Wha?, but we want to get as close as we can. Small audience, big artist.

They asked me, “How do we shoot this?” I said, “We do it with film.” I insisted on it. Video had already started, MTV was doing video, but if we're going to try to recreate the old days of Bob in the Village, let's get back to the roots. I wasn't going to shoot black and white, but you know what I mean. That was kind of the idea, and they hired me.

I thought I'd do it the same way that Marty [Scorsese] did, which was, let's just put six or seven cameras and show the show, as opposed to produce a show.

You mean sort of try a natural approach, as opposed to visual tricks?

Yeah, do it organically. You put a camera on Winston. You put a camera on Bucky. Tony, John Jackson. A couple of cameras on Bob. Just let the cameras roll.

My pitch to them, why it would be better for them to have me rather than some better-known filmmaker, was that I wanted to let the cameramen tell the story that they saw. Normally if you were going to do a shoot, you pick your Director of Photography, then that DP will hire his camera operators. Instead of me hiring one DP with his crew, I hired all DPs. I wanted each of them to tell a story with their camera. I’d sit down with each DP, tell them what their coverage was: Bob, Winston, JJ, Tony, etc. “You’re gonna tell the story about that person’s performance. You’re not gonna worry about what anyone else is doing.” Every camera was a story camera, as opposed to a coverage camera.

They went with that. We did two nights, four shows. Shot them all.

You probably know, but those shows have become legendary shows among fans. Dylan brought back all these songs he hadn't performed in years. It goes to show, I think, that he was taking the project seriously. It wasn’t a standard show that you could have filmed any other night that year.

There were two records in a row which were covers of traditional music, and that's what I was expecting. Basically a promotional vehicle for Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong.

What really blew my mind was when we were doing rehearsals for that show. I was expecting songs like “Blood in My Eyes.” But I think the first song they rehearsed was “Lay Lady Lay,” and then I got blown away by him playing “Queen Jane Approximately.”

You were expecting it to be entirely the old folk songs to promote the new records?

Yes. I was expecting it to be a vehicle for promotion. It was like touring behind the record, right? At that time, I was doing Mariah Carey and Michael Jackson and many big-selling pop artists, and basically, what you were doing was you were just promoting the record. There was no art to it. When he started to do things like “Queen Jane” and “Lay Lady Lay” and “Disease of Conceit” and “Ring Them Bells” and “Forever Young” and “My Back Pages” in the soundcheck, I was like, “What the fuck's going on here?”

Word got out pretty quick that Bob was going to do this. Once it did, there were people trying to do the same thing. I think Art Garfunkel called me. Eddie Fisher called me. I'm thinking, I can't wait to get home and call my mother and father and say I just spent 40 minutes with Eddie Fisher doing a walk-through at the Supper Club because he wants me to do the same thing I'm about to do with Bob. It was surreal, man.

I never made this connection before but a few months after the Supper Club, Johnny Cash started doing the Rick Rubin stuff. Then every other older artist who'd been forgotten was like, “Oh, I need to do a stripped-down back-to-basics thing.”

Me and Jeff Rosen created this thing called “Club Date.” I did the Pixies at the Paradise Club in Boston. I did Elvis Costello at the Hi-Tone in Memphis. That was the same concept.

These are all tiny places. That's sort of the idea, famous band in a small room?

Oh yeah. 250 people. I think the whole pitch was “the concert you always wish you could see” or something. I only did a couple of them, then I got bored with it. The Dylan thing was the template.

The obvious Supper Club question is: What happened? Why’d they shelve it?

Here's what happened. I did my cut, me and my crew, then Bob came in and watched it. He hated it. Which I didn't blame him for, because I cut it sort of in the spirit of that time, the ‘90s. I made a mistake, which was that I had shot it to not be a live show, and then I cut it like it was a live show.

What does that mean? What specifically would that look like?

It was MTV era. In those days, we thought that people's attention span was short. I think the mistake I made was I cut it more like it was a rock and roll show, as opposed to it being sort of an auteur thing, which is the way I shot it. I didn’t shoot it like a live show, but I cut it like a live show. I didn’t stay true to that concept

We did a screening in a small edit room at Sony Studios New York on 54th and 10th, and Bob hated it. He just didn't understand why you cut away from a solo. He had a different aesthetic perspective from a filmmaker; he had an aesthetic as a musician. I knew he hated it about seven, eight songs in.

How did you know? Is he expressing it in the room?

No, I just knew. I could feel it.

At this point, how long is it? Is this an hour for TV?

I think two hours, maybe. I was looking for a two-hour show. Each one of those sets was, I think, around an hour. They weren't long, because we had to turn the theater over.

I don't know if you ever been in the Supper Club, I'm not even sure if it's still open [it closed in 2007], but these were white-tablecloth round tables in a supper club where four people can sit at a table. They had candles on each table. It was ridiculous. It was so flashback.

Winston Watson told me it felt like a place for mob guys.

The thing is, I was wrong. Bob was right.

What happened was, when Bob said, “I don't like it,” we cleared the room. Bob and I sat down on this small settee in the edit room. Him and I sat right next to each other. Our knees were touching. I remember looking at him and saying, “What's wrong?” and he told me. We decided that we were going to re-cut the thing together.

When you say he told you, was it specific? “You're cutting away too much, the shots change too fast?”

In a way. Bob's a guy who's always in the groove. If Tony was playing a riff, but it wasn’t the lead riff, I would have a camera on closeups of his fingers. Bob didn’t understand why I was cutting away from him. But the audience didn’t want to see that. There was Bob’s vision, and then there was production value. You can’t bore an audience with something only a musician is going to appreciate.

For a director to be told, “You fucked up,” it's really hard to take. But in this case, I think he was right. It was one of those things where I shot it one way and then I cut it a different way. If you've ever been in that situation, you know how easy that is to do. A lot of directors make narrative movies where they follow the script [when filming], and then they don't follow the script when they cut. I didn't follow my own script, which was, “Let the cameras tell the story.” I turned it into an MTV Aerosmith music video. And this wasn't “Living on the Edge.” It was “Lay Lady Lay.”

But you've got all this great raw footage. Why couldn't you just recut it more to his liking?

We did. We decided at that moment that it would be better if the two of us sat together and did it ourselves.

You guys just sat there and worked on it?

Yes. For the next two weeks, every single day.

You and Bob?

Me and Bob, an editor named Rick Broat, my assistant Jennifer, Jeff Rosen, and that was about it. We went in every day.

I remember I got really sick at one point. Bob stopped off at a Hungarian restaurant and brought me this soup that was like drinking acid. I'm not talking about LSD; I'm talking about battery acid. That was going to cure me so I could keep working.

Did it work?

It was horrible. But the thought of it, I liked.

He would get driven every single day to the studio by Debbie Sweeney, who worked at the [office]. It's incredible that the Dylan operation was very small. Five or six people. People probably think that the Dylan world is like this massive two-or-three-hundred-million-dollar-a-year publishing empire. It may have been, but it wasn't run that way.

So me and Bob sat there and did that for at least 10 days. There was a Michael cut and there was a Bob-and-Michael cut. The Bob-and-Michael cut was the cut that we all agreed on would be the cut. When we disagreed about the pace or tempo, we would talk it through, and after a few days of doing that we had vibe going. He never took a stubborn “I'm always right” attitude.

At the end of the day, the reason why we've never seen it is because Bob never thought that the shows themselves were, to quote him, “in the pocket.” It wasn't my fault. Bob told me this: “It's not your fault.” The band just wasn't in the pocket. I'm not a musician, so I always understood that to mean that, no matter how great those songs would've been to the fans, they just did not hold up. But they actually do hold up.

That sounds a little frustrating. At that point, you're doing all this extra work recutting it, but if he doesn't think the performance is there, it doesn't matter how you cut it.

I never thought it wasn't there. I don't think anybody else did, but that was Bob's decision. He has a right to do that. He didn't owe Columbia/Sony a record or a video contractually, so he could shelve it if he wanted.

We mostly just have the audio, but I don't think any fan would think the performance was bad.

He's the artist. It does happen. I did the 25th anniversary of Steve Miller at Fillmore. He ended up not liking the outfit he wore and bought it back from my production company.

Bob knows what Bob knows. If he didn't think it was right, he didn't think it was right. If you listen to some of those songs, man. When he did “Queen Jane,” when he did “One Too Many Mornings” and “Ring Them Bells,” he was outstanding. But it was his decision. He's the artist. I've never resented him for that. I didn't care that the thing got pulled.

Well, I did care, I was pretty disappointed from a creative perspective, and because it was a lost payday to boot. But I had other things to do with him.

You don't get paid if it doesn't actually air?

I got paid, but there was a backend.

How did it end up that a few songs got released on that CD-ROM?

That was Rosen's deal. Jeff got Bob to let us pick three or four songs. I consulted on it, but the film is the film, and the CD-ROM has a different look. The original lighting design is very amber, very mellow. I actually had to get the fire marshal to allow me to let people smoke. I just wanted the vibe.

Like a '60s coffee house. Those Greenwich Village pictures, the entire audience is smoking.

Exactly. That's what I was looking for. The CD-ROM technology at the time didn't really translate the true look.

This is how the CD-ROM presented the amazing never-seen Supper Club footage:

Do you think it'll ever be seen, or has that ship sailed at this point?

I don't know. The crazy thing is that I have this stuff in storage. If you brought a DigiBeta player to my house tomorrow, I could play you the whole damn thing. I've been offered huge money for my masters, but I don't sell them. What am I supposed to do with them? The film is mine, but I don't own Bob's likeness or his publishing, so selling them would make it an unauthorized bootleg. I haven’t done that.

I interviewed one of the Tulsa archivists, and he said basically the Supper Club is one of the few things that, even if you go there for research, they won't show.

They don't show my shows at House of Blues during the Atlanta Olympics [in 1996] either. I shot two nights there and those were great shows. Except for the second being interrupted by the bomb scare at the Olympic Park. When the Secret Service were whisking us off, I was the last person out. I was like, "I'm not leaving until I get these masters."

The van was full. Tony was in the van. Uma Thurman was in the van. Ethan Hawke was in the van. A few other people. I was diving in kind of like that scene from Reds, where Warren Beatty is trying to catch up to the cart, and I'm carrying these freaking masters in my hands. We drove away with a police escort.

‘90s CONCERTS, MTV UNPLUGGED, WOODSTOCK ‘94

I did read you filmed some regular shows in the '90s. Was it just those two in Atlanta, or were there other shows you shot?

Oh, there were a lot of shows I shot. Not necessarily with multi-camera, but I used to tour all the time with Bob. I had a Canon Scoopic 16mm camera. Didn't have sound; I'd have to sync up with the board. I did a lot of that.

After Supper Club, I think the next thing was Woodstock '94.

When you say Woodstock, are you shooting the entire festival? Like what was airing on VH1 or whatever?

No. Woodstock ‘94 was a worldwide Pay Per View. See, there was a period of time where Bob would do these things and let TV cover him, but I was sort of the director's director. Even David Letterman's show, I took the chair.

What does that mean?

What that means is there were certain things that Bob didn't like the way he was covered. So [Dylan’s people] basically would say, “Yes, we'll do this, but Michael's got to oversee.” I don't want to put too much on Bob's vanity, because he's not really that vain, but there were just certain things that he really didn't like. He didn't like the up-the-nose shot and he hated fast cutting.

What would happen is that there'd be this prick that would come into the room and he would say, “I'm Bob's director, and this is the way we're going to do this.” As audacious as that sounds, that was my role.

You were the prick.

I was the prick. I'm going to tell Dave Wilson, after he's directed 250 David Letterman shows, how he's going to do Bob. Or I was the guy who would walk in at Woodstock '94 and tell the director, “I need to be in the control room, and I'm going to tell you when this shot doesn't work and when to take this shot.” I'm looking at 15 monitors and I'm saying, “All right, during ‘Masters of War,’ I'd rather you have the camera on the bonfire than on the stage.” They would have to say, “Okay.”

I can't say I directed Bob at Woodstock. I can't say I directed Bob at Letterman. But I was Bob's guy in the control room.

What was your involvement with MTV Unplugged?

I was credited as creative consultant. What that meant is I was doing the same thing I did with Dave Wilson on Letterman. I was essentially the overseer.

Overseeing MTV's people?

Yes. But it was much more collaborative; I was welcomed. I knew and worked with all those people. I didn't have to oversee anything. I didn't have to be the prick. They knew what they were doing. I think I had one conversation with Alex Coletti and Milt Lage, both very talented producers and directors, and I sat in the control room and let them do their thing. They were shooting at the studio that I ran, Sony Music Studios. The big sound stage there is where we shot Unplugged. We shot a lot of shows there. That's where we cut the Supper Club shows. That was my world.

I had this double life: I was head of the studio as VP of Film and Video production at Sony, but I was also Bob's guy at that time. It was weird. I just sat around and made sure that they didn't fuck up the way Bob needed to be shot. Unplugged was a well-oiled machine and Bob was comfortable there.

Was it the same idea as the Supper Club: remind people who he is?

Yeah. The idea was, get back to fundamentals.

I do remember that we were doing a show across the street from Letterman, Roseland Ballroom, and that was a big deal.

Was that the one where Neil Young and Springsteen came up?

Yeah.

Do you actually have footage of that?

Oh yeah. I got seven, eight hundred feet of footage. Black and white, or I may have shot color, I don't remember. I was just a guy with a handheld camera. I literally was Pennebaker, 30 years later. I was just shooting film.

What were you shooting these concerts for?

We knew we were going to do the documentary, No Direction Home. That was already in the planning. It was just for that.

No Direction Home is so focused on the '60s though.

No Direction Home, which eventually was going to become the Marty documentary, was actually my documentary. At that time, it was essentially just, “Let's take all the archival stuff and go back to the people that were involved.” So that was all going on, too.

I do want to ask you about that, but before we get there, how many concerts would you say you filmed?

It's hard to remember. I know Roseland was one. I used to do amphitheaters; we did a shed tour in 1995 or something up in Vermont, New Hampshire.

What would happen is I would go by myself, maybe with an assistant sometimes, maybe not. I'd rent a car, just travel around with them, go from Burlington to Franconia Notch or wherever. And I'd shoot. A lot of times, I just turned the film over. I would do the film-to-tape transfer, which is what you did back in those days. You took your film into a telecine room and you'd have a guy who was great at color correction like Gary Scarpulla take your fucked-up film and turn it into pretty good video.

Were you on stage shooting these shows? Were you just in the audience?

On stage, on the side. Stage right, stage left, audience pit, whatever. I had all access.

Did any of this stuff ever get used for anything?

I don't know. I'm in Tulsa. It's probably down the street from me [at the Dylan archives]. These guys are nine miles away from me. I've never been there. They've never even reached out to me. They probably have so much shit of mine.

Where did the Atlanta Olympics shows air? There’s video of both on YouTube.

I've done a lot of drugs in my life, but I have no record or memory of this ever airing. This was a union shoot, and there would be a record. I have a suspicion this was released by someone at the edit facility I was using for this. It’s my work, but those clips are clearly some kind of bootleg. Those rolling “creases” indicate a non broadcast format. Probably a 3/4" U-matic format or even a VHS, not a broadcast format. The tape quality is clearly a few generations down from the original masters.

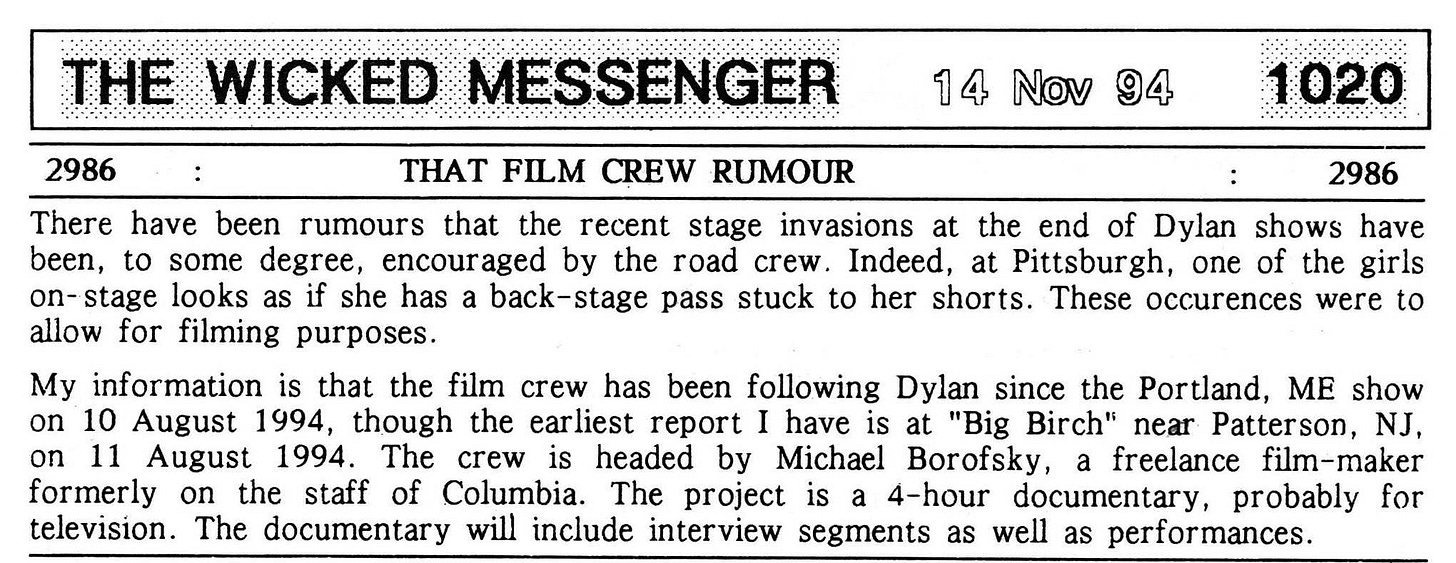

In the '90s, they were a number of shows with people stage-crashing, dancing with Bob, etc. Some reports at the time suggested that this was all staged for this project that you were filming.

No, not at all. I do remember that stage-jumping shit, but I never filmed it. I don't think it was anything [official]. Usually, we'd just toss them off. Bob was never really upset over these people. They weren't like attackers. They were just jazzed.

But that wasn’t for the documentary. Because the documentary was never about live performances. It was about what happened. Allen Ginsberg and Liam Clancy and Joanie Baez.

NO DIRECTION HOME

You filmed all those interviews?

I filmed all of them. I think Marty did one or two more. And he and Rosen did the Bob interview; that's what was different from my version of the doc. Marty made it more Bob-centric, and mine was more “witness”-centric.

Do you have a favorite interview?

Joanie and her mother, I can't tell you how cool they were. Even some of Bob's friends from when he was a kid. I had a couple of these interviews at my home. Pete Seeger at his house up in the Adirondacks, him and his wife making us one of those crazy hot stews. There were a lot of them, man. I was pinching myself that I was with these people.

I own the transcripts of all those interviews I did for No Direction Home—which is not what I called the movie.

What do you call it?

What Happened.

What Happened?

That was the working title. Because it really was just ‘61, ‘62 up to the motorcycle wreck. It was like the Hard Day’s Night of Bob Dylan world, but not done verité. There was obviously a lot of production value. Allen Ginsberg's interview, it was in Allen Ginsberg's apartment before he moved in. This was like two years before he died, God bless him and the whole loft is empty. I put him in a chair in the middle of the loft with these great old window behind him. It was an empty space of about 1000 sq feet, and sitting Allen down in an old wooden chair, he somehow filled the room.

You asked me what my favorite interview was. That's probably it. Not only because it was Allen Ginsberg, but because he was just so raw in it. He was naked, sitting in a chair in an empty apartment, and it was just so moving to me.

There is a great interview with Dave Van Ronk at the Bitter End, Liam Clancy at the White Horse Tavern. All those interviews were done with the subject in mind when I picked a location. Marty didn't use a lot of stuff I shot. There's so much, man. He had to leave some on the proverbial cutting room floor.

I also liked Tony Glover on the train. They used some of that footage for a cool little doc at the Dylan Center.

On the train and then we ended up at my house. That's my porch that you’re seeing. While Rosen and my daughter are sitting on the back of my Honda Civic in the driveway, and I have to quiet them down. I'm going, “We're picking up your voice on the boom mic.”

We picked up Tony in Albany or something, and we took that Amtrak all the way down to where I was living in Irvington. We drove the car to my house, and we put Tony on my porch, finished up with that sunset interview, which I'm not even sure is in the documentary.

You know how crazy it is to shoot on a train? The whole idea that I wanted to do was the whole on-the-road kind of thing. A guy by the name of Oliver Bokelberg was the DP on that shoot. The way he framed that, he was able to capture Tony and the window and the shit going by in the background. A whole hour and a half of the train ride and then another hour and a half on my porch.

Is Rosen conducting all of the actual interviews? Is he the guy asking questions?

We would work on the questions together before the shoot date. Rosen did most of the interviews. Then he'd go, “Michael, do you have anything to add?” and I would do my thing. The questions I asked weren't Bob-centric. They were more broad. More like, “I'm a child of the '60s” kind of questions. Let's talk about something no one had heard before. Enough water is under bridge now; tell us what really happened. That was my approach. Jeff was very good about the minutia; he had stuff in his head I didn't. He also had the ability to talk about who we were about to interview with Bob.

I have the transcripts of all of these. Every single one of them was transcribed. I don't know what happened to the actual raw footage, because every one of those interviews were like an hour long, and Marty may have used twelve seconds. I mean, they are fascinating. I always thought there would be a good book in just putting these transcripts together. I have reams.

So many of those people aren't around anymore.

People died before they even released the documentary. I was doing this over about four or five years.

Was Scorsese attached from day one?

No. Before Marty was brought on, I was the director. The reality of the movie industry is that you got to have somebody [famous] attached. That's kind of what happened.

Even if you've got Bob Dylan? Isn't he enough of a name?

I guess not. I think in the bigger picture, there was a decision that had to be made, which was, who's making this movie? “Michael Borofsky” was not exactly a bankable name. They were looking for financing and worldwide distributors, and so Marty joined the project.

How far had you gotten? Was there a first cut?

Mm-hmm. There were plenty of cuts. I have those, too. It's crazy.

You have to realize, this was Rosen's and Bob’s idea and I guess Kramer too. There was this idea that there was all this material that had never been put together: shows, appearances, captured video, film. Those clips were going to be something that would help this resurgence in the early ‘90s, to remind people that Bob was Bob. It evolved from that to, “Wait, let's go interview people.”

I never felt slighted by being bumped. I always got the whole movie-industry part. Let me put it this way: If someone's going to write a history of rock and roll, are they going to ask for you, or are they going to ask for Bill Flanagan?

I hear you.

I never took it personally. I knew I'd been fucked, but it was just business. It was like, “Okay, the BBC's ready to pay four million, but they ain't going to deal with Michael Borofsky's name attached. Let's get somebody else.” There was nobody else more logical than Marty. Marty actually watched dailies with me after the Supper Club. I've done two or three projects with Marty. I did The Blues with him, the whole history of the blues project.

Why was he there for the Supper Club work? Just as a fan?

He just wanted to come and see what I had done. He just showed up and we watched the dailies together. I'm not even sure if it was dailies; it may have been the film-to-tape transfer. He was like, “This looks great.” That's where my relationship with Marty started: Supper Club. Then we did the blues project together. He's always been supportive of me.

I did those two videos in Memphis, at the New Daisy in Memphis on Beale Street. They never released “Love Sick.”

“NOT DARK YET” / “LOVE SICK” MUSIC VIDEOS

What were you trying to accomplish with those?

“Not Dark Yet,” the idea was I wanted to show Bob doing Bob, because I love that song so much. I used this weird format where I use these giant Mylar things. I actually was shooting reflections and mixed it up in the edit.

Is that why it's all sort of warped or stretched?

Yeah. Bent. I was shooting into these 10-foot by 5-foot Mylar things that we'd set up. I guess the idea was, let's do this in a way in which you're not really there, but you are there.

“Love Sick” was a completely different thing. We had a two-hour break, and we broke the set down and built a whole new set. That set was an apartment building. It was a voyeur concept of looking at an apartment building from the street view, or another building's view across the street.

Like a Rear Window sort of thing?

Yeah…I guess. There are no original ideas, are there? [laughs]

It was a funny thing. We’d found a model [Rachel DiPaolo]. It was like Tony Garnier has got this girlfriend, Bob's the other guy, and it was just silly.

I went way out on this one, and this is why it never got released. There was this movie called Freaks. Actually, [Bob’s son] Jesse Dylan indirectly gave me this idea. He used to collect old photo cards of freaks, people from fairs, those people.

So what I did was, I took the movie Freaks, which I think at that time was in the public domain, and I combined the freaks and geeks in that movie [with my footage]. Somehow, I guess in my weird mind I thought “Love Sick” worked. I think it took Rosen about five minutes to go, “This ain't never going to go.”

So it was like intercut, half footage from the movie of the “freaks,” and then half this plot of Tony and his girlfriend and Bob?

Yeah. It was weird. I have a cut of it if you want to look at it. But it got killed.

Not only that, but I think Victoria's Secret had licensed the rights to use that song at the exact same time that I was about to show my finished product to Bob world and Columbia. They were just like, “Why do we need this?” That made sense to me too. If Victoria's Secret is going to pay you $2 million to use “Love Sick,” why do you need a music video? You're gonna get enough play on TV. People are going to be hearing “Love Sick” every day in little thirty-second increments. So why do you need my video?

Unfortunately, it never saw the light of day. Or fortunately. I don't know.

I'm going to say unfortunately, the way you're describing it.

The Bob and band footage looks great, but I think my concept of the lonely and exploited freaks—they were also called geeks starting in the ‘20s and ‘30s—was just too much in your face. But I thought the freaks were “love sick” in that film. They all wanted love, not because of how they looked, but because they had emotions and feelings just like so-called normal people.

It was pretty weird.

You say that like it's a bad thing.

No, I just think that I'm not on the same page. Bob as an artist is Bob as an artist. Me as a filmmaker is me as a filmmaker. They're two different things, man. I don't care…

…I did care, actually. I thought it was pretty cool. It would be more likely that it would show up not on MTV but on some weird channel, you know what I mean? It was just an obtuse version of, how do you take Bob Dylan singing about something that's really intensely personal-- If you listen to the lyrics of “Love Sick,” it's one of the most painful songs I've ever heard him write. I thought juxtaposing that with some pretty disturbing images made sense. That doesn't mean I wasn't wrong. It was just my vision of it.

Did “Love Sick” also have shots of the band performing, like “Not Dark Yet”?

Yeah. What I did with that one is, I got old lead glass windows from a prop house in Memphis. They just created this weird prism. I shot through this fucking glass with dolly shots.

The whole idea on both videos were that you never really saw [Bob directly]. “Not Dark Yet,” Bob was more present. I had that crane shot. “Love Sick” was more obscured. Alfred Hitchcock, I guess you would say. It was like, “What am I looking at here? Why am I looking at Bob now, and now I'm looking at some geek crawling across the floor from an old movie? What does it mean?”

Apparently, it didn't mean anything except to me.

What was going on with the model who was playing Tony's girlfriend?

There was a fight between Tony and Bob. It was like a dream. There were 16 windows. You'd see Tony in one window, and you’d see Bob with the model. She was just normal; that was the idea. There was no idea to exploit it. No silhouettes of women putting on hosiery. It wasn't like a Gil Elvgren picture.

It’s funny you're saying that and then the song literally gets used in a Victoria's Secret commercial.

That did not escape me. The whole idea of my puritanical, voyeuristic instincts was replaced by a Victoria's Secret commercial. It's about the dollars, man.

It was incredible, that whole period of time in Memphis. Like five, six days, prep, set building, rehearsal, blocking, all that shit. I think that was the first thing I ever shot of Bob where Larry [Campbell] was part of the band. I got to know Larry’s mom, Maggie, and she became really important to me. She was like the godmother of rock and roll stars. Bob’s world always had these great characters, and sometimes they weren't the main characters, they're the ancillary characters. Larry's mom was one of those people. One of those people that held things together in a weird way.

That’s the stuff about Bob world that is really amazing to me. These people were crazy interesting. You would come up with these people, like Phil Lesh and John Levinthal and Don Imus.

How was Phil Lesh connected to Dylan world for you?

He came to the Supper Club show. Him and the Allman Brother that was married to Cher.

Gregg.

I put ‘em in seats right behind me. Gregg fell asleep. But there was no spaghetti.

There are always those kind of people. They just show up. You'd be like, “Oh, my God, it’s Levon Helm!” You have to understand, man, I'm a fan. I was the director, but I was also pinching myself.

I was working with other people, too, with Leonard [Cohen], with Wynton [Marsalis], Tony Bennett. The Bob world was different. I was never starstruck, but I felt privileged that I got a chance for 10, 12 years to be in that world. And when they tell you you're not in the world anymore, they tell you.

That was an official decree of some variety?

I think it was true with everybody. You should know; you wrote the book on the band members.

Sure, but a band member kinda needs to know they're not in the band anymore. I would figure a director, they could just stop hiring you. They wouldn't need to announce it.

They don't really announce it. They just tell you, “We can't use you anymore.” They put it that blatantly.

I've always respected the Bob world. I got nothing bad to say about them. These are really good people. Jeff Rosen to me, he's just like a superhero, and that's on the record. He's an amazing brain, figured all this shit out, and has shepherded the last 30 years. This is a man who knows what he's doing. He's also a mensch. Just a good guy.

My children have great memories of Bob. They were like eight and ten years old. Living with Bob, going on tour with Bob, being on the bus with Bob, being with Bob's dogs, those goddamn Great Danes.

Did your kids get along with Bob? I remember Winston telling me he had a young daughter who just adored Bob, and they would always be talking backstage.

My kids loved Bob. There were times when I wouldn't even see my daughter for a couple of hours, and she'd be in Bob's tour bus hanging out. I remember one time, during the ‘96 World Series game where Charlie Hayes catches that foul ball against Atlanta, we’d actually delayed the show to listen. My daughter and Bob walk out of his bus at the end of the game. He goes, “That Charlie Hayes—that guy's a tank.” And my daughter just was laughing so hard.

He had these dogs, these Great Danes. My daughter's favorite was Felix. I think there was another one named Buddha or Bubba or something. My son, who was younger, he'd hold onto that dog's neck and literally ride it backstage.

Those are great memories. I'll tell you what, I got no bad feelings about the decisions they made when they made them. They didn't release the Supper Club. Okay, got it. I've watched it. It's good. It's really good, actually. It's a shame that no one's seen it. Not because I didn’t get the director credit, but it's just a shame because it's so cool. It's one of those moments where people go, “Is he over or is he back?” I got to capture that. I got to prove he's back.

Thanks to Michael for sharing his stories! Hopefully one day we’ll get to see the lost “Love Sick” video and more of the Supper Club shows.

For more on Dylan on film, check out my conversation with director Gillian Armstrong about filming Dylan and Petty for ‘Hard to Handle.’

PS. As I mentioned a few days ago, I’m newly on self-imposed paternity leave, but the newsletters won’t stop. These are already scheduled and ready to go, so subscribe now to get ‘em sent straight to your inbox (the first two and fourth will only go to paid subscribers).

Great interview, Ray. Fascinating behind-the-scenes stories I've never heard before. I would love to get my hands on those transcripts from interviews for No Direction Home (aka What Happened).

I think Borofsky was referring to Hal Gurnee when referencing the Letterman show. He was the director at the time. Dave Wilson was the director of SNL. Dylan was on SNL but in ‘79 only.