Concert Producer Talks Putting On Dylan's 'Hard Rain' Concert

An interview with the show's Director of Production Rick Wurpel

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

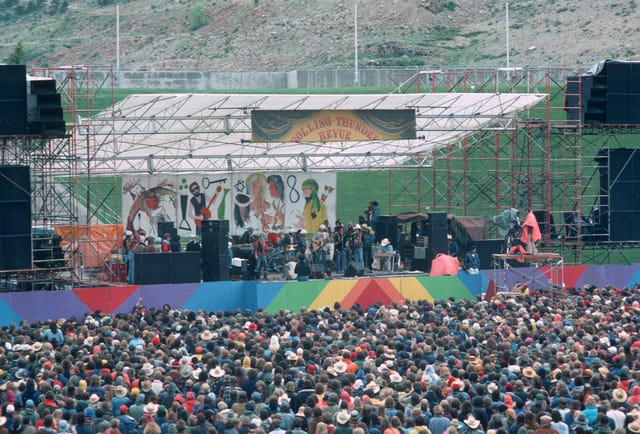

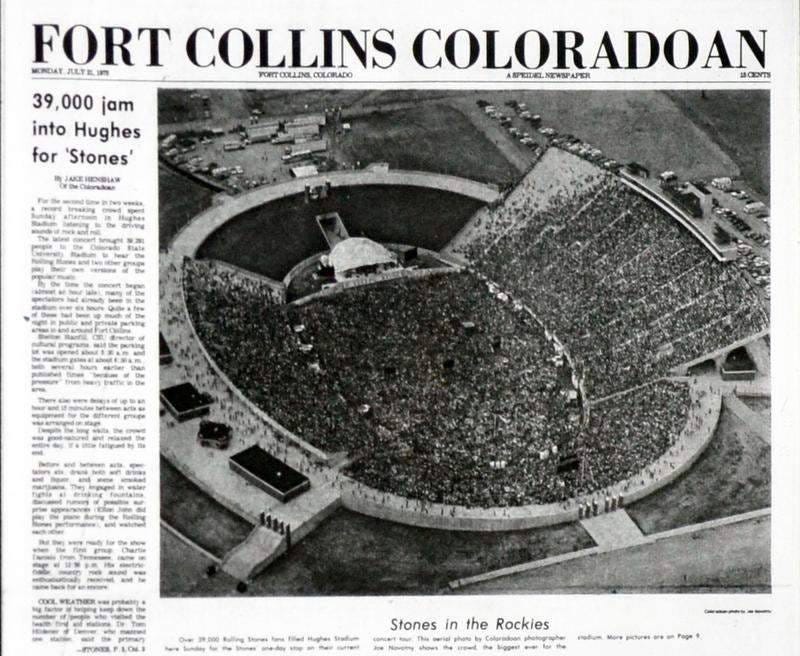

On today’s date in 1976, Bob Dylan held the second-to-last Rolling Thunder Revue concert, which would get immortalized in the Hard Rain film and on the live album of the same name (the latter also included a few tracks from Fort Worth). The show took place outdoors in Fort Collins, Colorado, and the titular rain was no metaphor; it poured all day.

Today I’m sharing an interview I did a while back with Colorado concert producer Rick Wurpel. He was their man on the ground in Fort Collins, the Director of Production in charge of everything from the local side of it. When Dylan’s giant touring crew rolled in, he was their point person who’d already scouted out the venue, figured out how the show will work in that particular space, and thought through answers to any question they might have. He oversaw many of the literal nuts and bolts of putting on the show, including renting equipment, setting up the stage, dealing with the local authorities, handling the film crew’s needs, putting out various fires during the show itself, paying the bills, and sorting through the aftermath.

When he started working to plan the show, it wasn’t supposed to be anything special (at least, not more special than any other Rolling Thunder concert). It was only shortly before that he learned there would be a whole film crew coming. Below, Wurpel tells his part of the Hard Rain story.

How did you get involved in it in the first place?

I'm originally a theater guy and was working at Juilliard. I was what was called the master carpenter, which is the guy overseeing the building of the scenery and props and all of that stuff. Juilliard was closed for the summer. I was supposed to be doing a series of musicals at a small college in Denver. The idiot producer that was putting it on, didn't understand his Equity rules. He had an Equity cast with student support and student construction. The union threw the picket line up on opening night.

The thing closed, so I jumped into the world of music, producing shows. This promoter Barry Fey called me up one morning and said, "Please come in and see us," because I had a pretty extensive resume, especially for the music world at that time. I did a contract with Barry, who was at that time partners with another promoter, Bill Graham.

Long story short, I got told about 20 or 30 days before that we're going to do this Rolling Thunder Revue show up in Fort Collins with Bob Dylan. Barry Imhoff was the tour promoter. Between Bill Graham and Barry Imhoff and Barry Fey, they were a bunch of loud screamers who were difficult to work with, especially for a guy who came from the world of “this is all about the audience and that is why we're here.”

Anyway, I was brought in to handle the local production of it. It wasn't like today where Taylor Swift arrives with 140 semis full of everything in the world, including the stage, the sound, the lights, the runways, the barriers, the security, the dressing room furniture, on and on. Although Rolling Thunder Revue did bring a horrible roof stage cover.

Had you staged shows in that spot before?

I was going in front of city councils and university regent boards and athletic departments trying to get them to do shows at those facilities. That was still the era where there was a lot of fear about doing these horrible rock and roll shows. “Are we going to get the money?” Some of the promoters were a little unscrupulous.

That facility [Hughes Stadium at Colorado State University] I had been into the year before with both the Stones and a Chicago/Beach Boys show. The university was okay with it. I had them, for lack of better terms, well-groomed. Shelton Stanfill, who was head of the cultural events division of the university, was a guy who produced everything from Broadway shows to very eclectic film festivals. His list of things the university should do included popular music.

Before the musicians and everyone else arrives, what is your job?

My job is to interface with the facility and with the university. I am the person in charge, from their point of view. Because I had an independent production company, I had a contract relationship with the university and was looking out for their interest and making sure that this thing could happen in their facility and not destroy it.

Unfortunately, that was not the case in this instance. We had horrible weather. The field was totally destroyed.

I heard the stage go soaked too.

Portable stage covers didn't really exist. There were all kinds of people trying all kinds of different things. One of the covers I used for the Chicago/Beach Boys was literally a vulcanized canvas cover that was stretched between brick masonry towers. My concern about anything going over the heads of artists, as well as workers, was that it be structurally sound.

The roof came with the tour. I knew the rigger, Arthur Russo, called “Torch.” He had assured me that this roof stage cover was well designed. Unfortunately, when he showed up with it, in this layman's opinion, it was not structurally sound at all. There were welds that were breaking. It leaked like a sieve.

I was also very surprised to learn that there was going to be some company coming to film this. Again, this is back in the day when the technology of capturing images, especially music shows and especially in an outdoor situation, just didn't really exist. It was all trial and error.

The night before the show, I went to get some sleep at about three o'clock in the morning. Got a call about five or six. My assistant was freaked out because a film company had come and muscled their way into the rampway that led to the back of the stage and parked a 40-foot trailer there. It's film, so I have no idea why they needed a 40-foot trailer, but anyway, they had parked it in front of the garage that housed the forklift and assorted show equipment we needed.

The film people were from LA, and they had the LA attitude of, "If we don't get everything we need, we're not going to be able to film this. If we're not going to be able to film this, Bob's going to be upset.” All this crap. Totally obnoxious. They had no fucking idea what they were doing on-site. They're used to shooting in a studio or a soundstage. Once they get off into the wilderness, they can get a little tweaky.

I was freaked out because of the way they had parked the trailer, because the tunnel was very narrow. They had sent their truck driver away. There’s this other character who is now one of the top tour managers in the world by the name of George Travis. He was a truck driver on that tour. George walked over to me and said, “Fear not, Rick, I can do this.” He got his tractor down, hooked the trailer, and was able to yank the thing out of there. We could get to the forklift and the equipment we needed for the show.

So what happens on show day?

The audience came in, and, of course, it was raining like crazy. Everybody was soaking wet, and everybody was grumpy.

All of a sudden, one of my people comes running up to me. “Rick, you got to go get out front!” I go out front and there's one of the TV people trying to move some of the crowd away from the front of the stage, because they decided they wanted to have scaffolding put up in front of one of the speaker towers. So they wanted to displace 100 people that had been sitting there for at least an hour, if not two, in the freaking rain. The people were up in arms. I was pissed off. Somebody else came out and said, “Wurpel, please, let's just take it easy.” I'm like, “But you don't do this to people. This is just not right.” We wound up doing it anyway.

In a weird way, karma got both of them. The TV people grabbed our local carpenter. I'd known him since he was 12 years old. They started berating this guy about, they needed some table [built]. He didn't have any lumber available to build them a little table. They’d seen some scrap lumber around and said he should go get it. They pointed to what they thought was scrap plywood. He cut it all up and built them a little table.

Somebody right before showtime, “Wurpel! Wurpel!” “What?”

“Who the fuck cut up Bob Dylan's paintings of Christ?”

Oh no…

He had painted these pictures of Christ on four-by-eight sheets of scrap plywood. My carpenter, under the pressure of the TV people, grabbed that scrap plywood and cut it up and made a table of it.

Do you ever get blowback from Bob or his people? “What happened to my paintings?"

Yes, everybody was really upset. “Who's the idiot…?” Again, this carpenter was one of my closest friends; he later became my brother-in-law. I wasn't about to throw him under the bus. I was like, “I don't know what happened.” In my mind, I'm going, “It serves you LA filming guys right for throwing this crap on top of us at the last minute.”

Did all the rain delay the show? Were people just waiting for hours?

That was a smaller stadium. It was 30,000 people. Because of the size of the show, you let them in early. The facility concessionaires love it, because they want to make some money. That's part of what the university is in it for, their till that they're making. They were in probably three hours, four hours before the show. They were putting up with a lot of wetness. It wasn't summer yet. It wasn't freezing cold, but it was cold.

Is this what destroyed the football field, hours of people walking on the ground?

Absolutely. The field wasn't grassed properly; it didn't have the right drainage.

This is hallowed ground. It’s all about football here. There are still stadiums across the country where football is so strong that there are no stadium concerts allowed.

I took the athletic department and the head coach and they saw the field. Not only is it thigh-deep mud, but there's boots, there's shoes, there's garbage. I hate to use the term right now, but it looks like a war zone. The athletic director and the coach, they were both in tears. I was trying to get them settled, saying, “The insurance will cover it. It's May. You don't have football ‘til August or September.” They were devastated. They were like, “There will never be another concert in this building.” I'm not sure there ever has been another one there.

Then the other craziness that was going on: this was Passover. Barry Imhoff comes running up to me. “Look, motherfucker, we need a blender. We need it right now."

Of course, when you're in the middle of producing a fairly substantial show and it's crazy anyway and there are lots of nuts running around, when somebody says they need a blender, it's not the top priority on your list. Barry Imhoff just went absolutely crazy because I wasn't being responsive to this request. I finally said, “What is it for?” He goes, “It's for the seder.”

I said to Barry, "Barry, I've been through a few seders in my life. I remember bones, and I remember horseradish. I don't remember a blender."

That really pissed him off. I said, “I'll find a blender, but what's it really for?" I think it was for daiquiris. The daiquiris at the seder.

Ah yes, the seder tradition handed down for generations: the daiquiris.

It was a circus, but it probably wasn't the worst show circus I've ever seen. One of my clients for years was Willie Nelson. Willie had moved from being a club act to 1,000-seaters to all of a sudden he was able to do 9,000 and 10,000-seaters. His backstage, there’d be 500 or 600 people, a half dozen kegs of beer. The world of cocaine was just appearing. It was moving from the stockbrokers to the rock and rollers and got very heavy. The crew would show up drunk or high at six, and he'd show up for soundcheck at eight. Then he'd get on stage at nine or ten and they'd want to play till two or three in the morning. That's not good for the audience; that's ridiculous. He wasn't making money; the promoters were making money. I got him straightened around.

We've been talking mostly about the setup. What are you doing during the show itself?

Putting out little fires more than anything. It could be everything from the school didn't get as many passes as they needed or the electric went out in the dressing room or there’s a buzz in the sound system. A myriad of little problems like that, as well as trying to get all of the bills together. That was my responsibility: to reconcile all the bills. The roof, the stage, the sound, the lights, the security, the ticket takers, the facility, the advertising, the lender, on and on and on.

You're doing that during the show itself?

I am. This is pre-computer days; this is all manual labor. This was also before there were a myriad of tour accountants. It was part of the production stage manager's job to do this shit. Getting involved in things like, “That roof didn't really work, why should we be paying full price?” “Bob wants to play an hour more, which means the labor cost is going to go up.”

Was that something that happened, he wanted to play longer, or is that just a hypothetical?

He did play a little longer, because of the crowd being in the rain and having been there forever. My understanding was that he wanted to play a lot longer. It was a torn thing, because the band was also cold and wet because the roof leaked. And this was not the days of wireless everything. This was the days where you were wired. So there’s also, in the back of your mind, the knowledge that electricity and water does not mix.

If you got puddles on the stage and wires dragging through them, that's trouble.

You got it. But you’re talking about a mean age of probably 28. We think we're invincible. It's not like everybody's frightened, “Oh my God, we’re gonna electrocute Bob!” But it’s definitely in the back of your mind.

If I had been in charge, I would do what I used to do up at Red Rocks. I did five seasons up there without any stage cover. I would go acoustic. I held umbrellas over people’s heads while they played acoustic, whispering, “Don't touch the microphone.”

Are you having much interaction with Dylan himself? It sounds like that's maybe not a huge part of your role.

No. Again, in my world, that was sort of a no-no. If you didn't have any need to be working directly with the artist, you didn't. Now that I'm 71, I look back like, well shit, you should have been a good host and got to know all these people.

Bob plays his last note, the band leaves the stage. What happens next? What's your job in terms of taking down the stage and wrapping everything up?

He plays his last note, leaves the stage, and then we've got that hole. I'm always the one going, “If he's going to do an encore, we need to get him back on stage.” I wasn't a big fan of, get off the stage and go in the dressing room and fuck around for five or ten minutes and then go back. I was a proponent of, the artist walks behind the amps, stands around for a while, if the audience is enthusiastic enough and he had performed a decent enough show, then turn around and go back out there and do the encore.

He did do an encore, I forget what the song was. [It was, appropriately, “A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall,” one of the only times it was performed on the ‘76 tour!]

Then the university personnel would come to me and say, “How soon can we start taking stuff down?” Of course, they have Physical Plant people doing stuff with water lines and electrical and trash and garbage and cleanup and all that stuff. “When can we start? Has the tunnel cleared? Have all of the artists cleared out?” All of those arrangements are now being made, pretty much off the cuff right after it’s over. We’d need to wait and make sure that all the punters and the artists and the guests are out of there. It’s like, “Folks, playtime is over. Go away and let us do our work.” Because we're tired. It's been a hard, rough day. We're not going back to the hotel for cocktails. We're not leaving until anywhere from 18 to 48 hours from now.

Usually, the sound equipment loads out first and if there's any lighting equipment—there wasn't much on that show, if any—that goes, then you probably would bring down whatever’s left to the roof. Then it's my job to meet with the athletic director and coach and walk them around the field.

A year before we had done Chicago/Beach Boys, and I had created a volunteer medical response team. 100 doctors, nurses, everything. I had them go out into the crowd and hand out trash bags. Throughout the day in the break between the acts, I was always making announcements about, “Please, go pick up your trash, put it in the bags.” After the Chicago/Beach Boys show when I stood on the stage and looked at on the field there was not a drop of trash. Probably 1,000 trash bags filled up.

Now, a year later, standing there with a distraught and crying athletic department director and coach— You could see if somebody had been smart enough to come in knee-high boots, there'd be one sticking there where it’d gotten stuck in the mud. This wasn't a Grateful Dead crowd, but it was a Bob Dylan crowd: “I don't need my shoes, I can walk out barefoot.” I wish I had a good artist friend that could paint a picture, because it was quite spectacular. There was not a blade of grass left. There was nothing but mud.

Thanks Rick! If you’ve never seen the full ‘Hard Rain’ video, check it out here:

Plus an outtake:

1976-05-23, Hughes Stadium, Fort Collins, CO - complete concert

For more ‘Hard Rain’ stories, check out the oral history I put together a couple years back:

An Oral History of Dylan's 'Hard Rain' Concert

On September 14, 1976, NBC broadcast Hard Rain, a concert film recorded at the second-to-last date of Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue. Taped in Fort Collins, Colorado, the film earned its name for taking place outdoors after a days-long downpour. It’s never been released on DVD or streaming, but the footage circulates widely.

Can't get over destroying a Dylan painting of Christ to make a table. Nice to see that one painting survived: the rock 'n' roll Jesus playing behind Dylan in the backdrop. You could try a hundred times and not get a more perfectly symmetrical alignment of the two guitarists. What a visual! Who needs a silver crucifix from the audience when you've got the big guy himself hovering above you on stage. Another revealing interview, Ray. Here's a seder daiquiri to you--L'Chaim!

My wife and I just had lunch at the Stanley Hotel last week, where the RTR stayed during this time.