Bob Dylan's First Manager Terri Thal Talks Greenwich Village and 'A Complete Unknown'

"I needed something to play for club owners, so I cut a tape at the Gaslight. Everybody said, 'Go away.'"

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

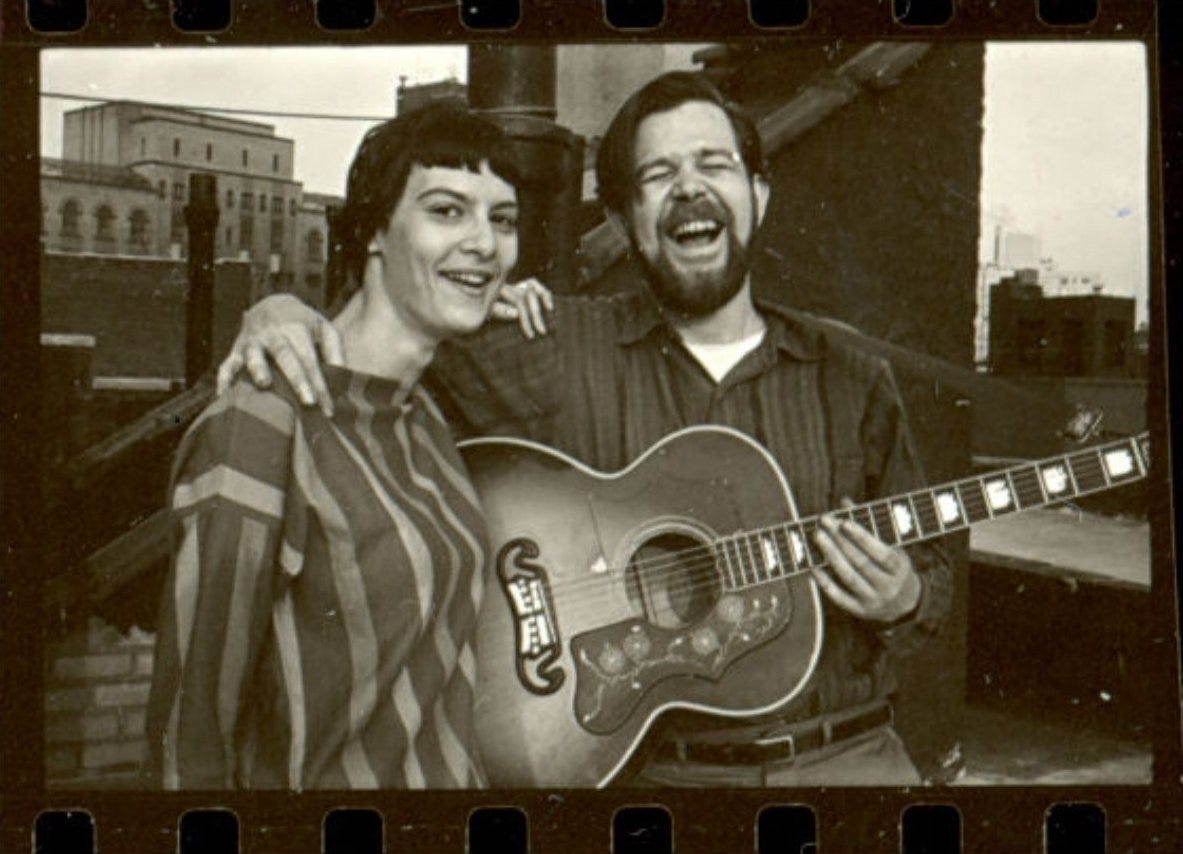

Before Albert Grossman, Terri Thal was Bob Dylan’s first manager. Though, as she would be the first to admit, she was no Albert Grossman. Closer to a friend helping a newcomer get gigs, just as she was doing for her then-husband Dave Van Ronk. Dylan writes about her in Chronicles:

Van Ronk’s wife, Terri, definitely not a minor character, took care of Dave’s bookings, especially out of town, and she began trying to help me out. She was just as outspoken and opinionated as Dave was, especially about politics — not so much the political issues but rather the highfalutin’ theological ideas behind political systems. Nietzschean politics. Politics with a hanging heaviness. Intellectually it would be hard to keep up. If you tried, you’d find yourself in alien territory. Both were anti-imperialistic, antimaterialist. “What a ridiculous thing, an electric can opener,” Terri once said as we walked past the shop window of a hardware store on 8th Street. “Who’d be stupid enough to buy that?”

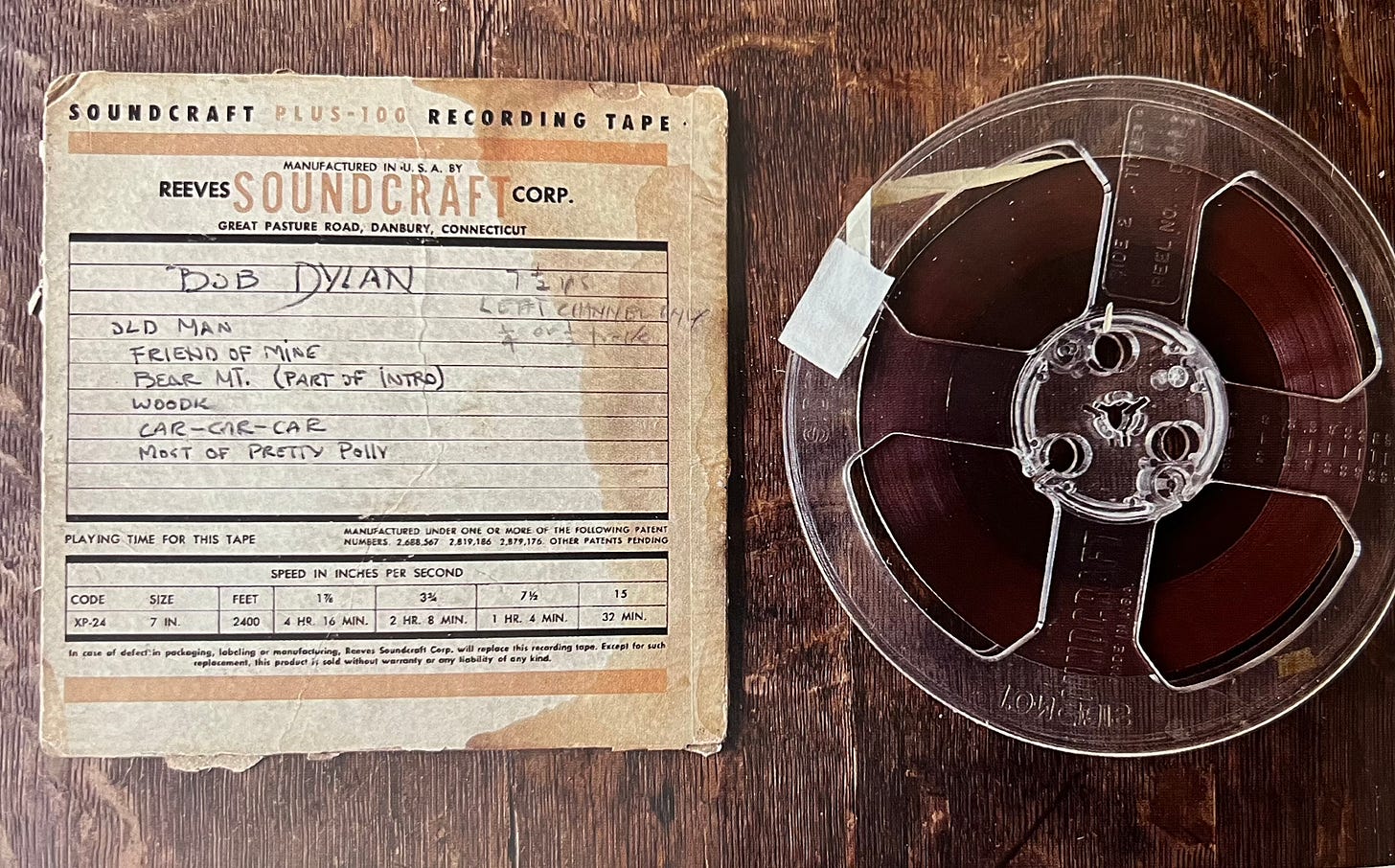

During her six months as his manager, she made one huge contribution to Dylan’s recorded history. Looking for something to bring to club owners outside of NYC to convince them to book him, in September 1961 she recorded what would be become known as The First Gaslight Tape, one of his first concert recordings (the very first of a “regular” concert, since both Indian Neck and Riverside were special events). A recording Dylan fans have treasured for decades—even if the bookers at the time didn’t care.

Even after the manager bit ended, she remained friends with Dylan for a few years, and with Suze Rotolo for decades longer. She also remained close to Van Ronk even after they separated, after, as one chapter in her memoir My Greenwich Village: Dave, Bob and Me titles it, “Eleven Years and One Month.”

I spoke to Thal about those early-’60s Village days and what managing a 20-year-old Bob Dylan entailed. Plus I wanted to get her take on A Complete Unknown as someone who was actually there. “I’m not looking dispassionately at history,” she explains. “I’m looking at portrayals of friends.”

I have a lot of very specific questions but I’m going to start with a super broad one: What did you think of the movie?

I thought the movie was pretty good, which surprised me, because I am a very literal person. When I look at movies, I really want to look at biography, and this is not biography. It’s biopic, where the producers create an arc and move to whatever conclusion they want.

Did the early scenes, especially the Greenwich Village scenes, feel true to your experience?

The feeling, the tone, yes. I think they captured a lot of it quite well. Coffeehouse scenes, Village streets. That’s not exactly what it looked like, but it doesn’t matter.

I was curious about the coffeehouses specifically. Did they actually look like Gaslight and Gerde’s?

It was close enough. It was the feel rather than, did the Gaslight have those kinds of light fixtures, or were the tables in that scene arranged in three rows front to back the way the Gaslight tables were arranged? I don’t even remember what the Gaslight tables looked like. It had the look of the inside of a club.

But, depending on what scenes you’re talking about, I have problems with a lot of it, because I’m not looking dispassionately at history and saying, “Oh, somebody changed the history.” I am looking at portrayals of friends—and, in a way, portrayals of me, even though I’m not in it. It almost isn’t even a question of accuracies or inaccuracies, but of changes or distortions of people.

Dave is in the movie briefly a couple times. Did you know going in that there would be a Dave Van Ronk character?

I did. I saw the movie twice. The first time I didn’t even realize that that guy was David. It just went right by me. I think he was there once later in a party. I saw somebody with hair hanging down like David, so I guess that was Dave.

He’s in there very early on, telling Bob where Woody Guthrie’s hospital is. Plus that one line later at a party.

My feeling about that is, and this is a little difficult to explain, but Bob is on his way into New York to meet his hero. His hero is somebody who is part of a world that he’s going to leave. He’s coming into the folk music world, which he is going to leave for a different musical world. Dave is there to greet him before he even gets there. Dave is never seen again. The way David was set up, to me, it was like saying, “This guy is part of the world that Dylan is going to leave, which is a failing world.” I thought that the way it was done was insulting to Dave.

The only really political scene is the Cuban Missile Crisis, which is portrayed I think quite well. They show the fear. People were really, really scared that night. They were terrified that they weren’t going to be alive the next morning. That the whole thing was going to just be gone. The movie shows Bob working in the Gaslight that night with a very small group of people riveted, listening to him. Then Joan Baez running to be with him because Suze is away.

Aside from the Joan piece, Dave was working in the Gaslight the night of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The audience was small; Dave usually packed the Gaslight. People didn’t go out that night. They didn’t go to hear musicians. It was a small crowd, but the small crowd were people who were riveted listening to David, as they are shown riveted listening to Bob in the movie.

I think that it was insulting for them to replace David. It was like Dave didn’t exist.

You’re saying that was Dave’s story, playing the Gaslight during the Cuban Missile Crisis, not Bob’s?

I was there. It was my story too. A piece of my life is erased in some way. I wasn’t a performer, but it was an important night in my life. It was an important night in the life of anybody else who happened to be in that room. They didn’t have to do that.

You mentioned there wasn’t too much politics in the movie. One scene I got more out of having read your book right beforehand is when the Suze character [named “Sylvie” in the film] encourages him to be more political, to get more into activism. There’s some line like, “You don’t need to be singing songs about the Dust Bowl. There’s issues happening right now you can write about.”

He did to a certain extent, in his own way. As a songwriter, Bob evolved brilliantly. He started by writing rapportage, whether it was about past events or present events. He moved into writing metaphor, which no one else was doing, or not doing well.

The movie, however, totally ignores the whole Civil Rights movement. It just ain’t there. That’s what I went back to see. I went back to see the movie because I said, “Am I really correct? Did this movie simply skip that whole thing?” This was years of really important political conflicts that were going on. It did show him singing at the March on Washington, which was an important event.

You were there right?

I was at the March. Dave was supposed to sing. He got sick, but he urged me to go. I was up on the platform, not because of who I was, but because of Dave.

Bob was not a political person in my terms. I was a committed, active Marxist. Our friends in the folk music world weren’t, for the most part. That was another really important part of my life and Dave’s life. But Bob was not uninvolved with what was going on. He did go South at one point. All of this was just totally ignored. It’s like it didn’t happen. In the movie, he comes to New York, he lives at a distance from this changing, growing Civil Rights movement. He goes to where a lot of people regard as its pinnacle, the ’63 March on Washington, and that’s it.

One line from your book I thought was interesting was that he would come to your apartment and you and Dave would tell him all this political theory, what you were passionate about. You felt the theory part he was uninterested in. It was more specific events that resonated for him. The story of Hattie Carroll, say, rather than concepts about Marxism, socialism, capitalism.

I didn’t know anybody from the folk music world who was really interested in the Marxist stuff that Dave and I spouted. That really wasn’t part of it. There were people who had been part of left-wing movement years ago; even they weren’t that interested in it anymore.

In Chronicles, when Dylan writes about you, he says a version of the same thing. He writes, “She was just as outspoken and opinionated as Dave was, especially about politics. Not so much the political issues but rather the theological ideas behind political systems. Nietzschean politics.” It goes on for a little while.

Did he say Nietzschean or Marxist?

“Nietzschean politics.”

No. No way. I couldn’t tell you anything about Nietzsche.

The anecdote he shares after is about you two walking by a store. He’s saying how you’re anti-materialist and you say, “What a ridiculous thing, an electric can opener. Who’d be stupid enough to buy that?”

I read that. Did I say that? I have no idea. I could have.

Let’s rewind a little bit. In terms of your own story, talk about how you entered the Village folk scene and how you met Dave, before Bob even comes into the picture.

I backed into it through left-wing politics. I went to Brooklyn College, and when I was in college I actively sought out organizations that were left-liberal. I went to socialist meetings every Friday night, and all of the left-wing organizations met in the Village. I had been going to the Village with a high school friend even before that. I had heard some of the folk music in the Square on Sundays so I had a little bit of that background. I was very young.

Are we talking late ’50s now?

We’re talking mid-’50s. I graduated from high school in June ’55. I’m going to these socialist meetings in the Village in ’56, early ’57. I am accosted and interviewed and grilled by the FBI. I tell them to go away.

Just for going to the meetings, the FBI is on you?

All I was doing was going to meetings. I knew a lot less about the organizations they were asking me about than they did. This was the tail end, during the McCarthy period. I remember these guys walked up to me on the street. They said, “Terri,” and they showed me their FBI cards. Without even blinking an eye, I looked at them and I said, “I won’t name names.”

During the McCarthy period, people were summoned to Washington and asked to name people they knew who were involved in the Communist Party. I only knew people in socialist organizations, not the Communist Party.

Anyway, I was going to these meetings, and the world was very small back then. There were only a few hundred people in it. The socialists knew the folk singers, knew the science fiction people, knew the visual artists. Everybody hung out in the Village. That’s how I backed into folk music.

I met David at a science fiction party. We talked for a while. I didn’t see him again for several months, and then I ran into him in the Figaro, which was a coffeehouse that everybody I knew hung out in. We were together for another 11 years.

What precipitated you becoming his manager?

David hated business. David wouldn’t set foot in the bank. When we started to live together, I had to talk him into being on the checking account. He hated that. He just didn’t want to have anything to do with it.

He would just be keeping all his money hidden somewhere?

He didn’t have any money! There was nothing to keep. Starting a checking account was wishful thinking.

He had this gig in a new club somewhere not too far from Philadelphia. [The club] was bombing; it wasn’t attracting an audience. It was pretty obvious that he wasn’t going to get paid, because they weren’t making any money. We called his manager. His manager said, “Work out the gig.” It was a perfectly reasonable thing to tell him. Work out the gig, and then we’ll…what? We’ll sue? I don’t know if you’ve ever heard the adage “you sue a beggar and you get lice.”

But he did it. He worked out the gig. He didn’t get paid. He fired his manager because he was pissed with him. Why did he hire me? I don’t know. I was there.

How do you learn the ropes? You’re not a manager, until suddenly you are.

You wing it. It was not such a big deal then. There weren’t an awful lot of commercial managers around. You had Albert Grossman, who was an up-and-coming commercial manager. You had Harold Leventhal, who was a very experienced, incredibly honest manager in New York. You had Manny Greenhill in Boston. Basically, in the beginning, I was a booking agent. I just called clubs and got gigs. It really was trial and error.

I was not the kind of manager who tried to change his music or the way my clients looked or acted or teach them stagecraft. I just took them as they were. Some people sent their clients to learn how to dress better or speak better. I didn’t do any of that.

When I managed, a good deal of what I did was PR. My clients had a ton, given the time, of publicity. I did an enormous amount of public relations for them. I had interviews, I had press coverage, everywhere they went.

What does public relations look like in the early '60s? You’re writing press releases? You’re inviting reporters to shows?

At that point, it was both. I looked up who and what newspaper or what magazine would be interested in folk music. There were damn few people, of course. I had lists of names. I had phone numbers. I called them. If I went to another city, I met them. I did all that shit that a good PR person I thought was supposed to do, which was personal. I didn’t just send press releases. As a matter of fact, I barely even knew what a press release was.

I remember, I think it was 1964, there was a thing called the New York Folk Festival. David did the blues concert. He brought in Chuck Berry, who had gotten out of jail a while before and had not been around for very long. There was a guy who did PR. I saw the press releases and I said, “Oh, that’s what they do.” I had just always done letters and phone calls and personal shit.

Were journalists generally interested in a new folk artist?

No, they weren’t. By ’64, ’65, there was some interest. Before that, outside of New York, it was rough. It really was. I put a lot of time and work into that, and I was good. When I stopped managing, I did public relations for not-for-profit organizations for years.

Where you pitching Robert Shelton, or was he plugged in enough on his own?

He was around. He was very aware of what was going on in the folk music world. It wasn’t a question of nagging him very much. He knew who was there.

Was Bob your second client after Dave?

Yes, he was. That was ’61. I had just started to work with Dave.

There’s a scene in your book where Dave has seen this kid out in one of the clubs, and he comes back to the apartment and calls him a “fucking genius. Then you go out and see him and you agree. What about that early phase of Bob Dylan made you and Dave think he was a “fucking genius”?

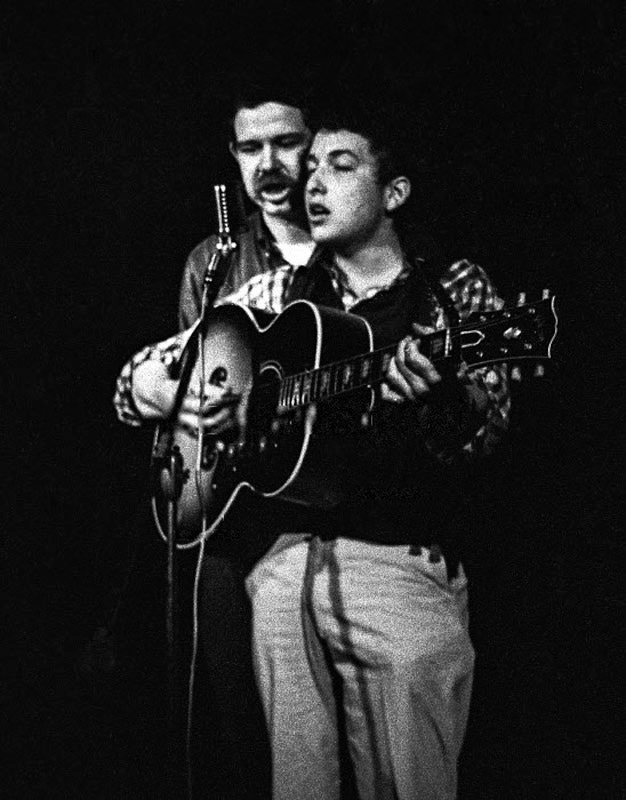

People ask, and my answer is always, “I don’t know.” He stumbled a little bit and he looked cute and he doffed his cap and he walked and acted a bit like Charlie Chaplin. He was not a great guitarist. He was not a great singer, but something-- I can’t put my finger on it, what there was about him.

It wasn’t only Dave and me who thought that. Within weeks, that guy started to become the most photographed folk singer in Greenwich Village. Other folk singers were more enthusiastic about him than they were about anybody else.

This is even before he’s writing his own songs too.

Yes, those first months. This wasn’t in the rest of the country or the rest of the East Coast, where he wasn’t yet known. This was in the Village.

How do you go from being a fan to being his manager?

He says to me one day, “Would you get me gigs?” We talk about it. I say, “Do you want me to manage you?” He says, “Yes.” We work out a verbal arrangement. Never occurred to me to ask him to sign a contract. I wasn’t that professional yet.

Initially, all I’m going to do is try and get him some work because he has to earn a living. I needed something to play for potential employers and club owners, so I cut a tape at the Gaslight. I took it to Philadelphia and I took it to Boston and I took it to Saratoga Springs. Everybody said, “Go away.”

When you say “took it,” are you making copies and mailing it out? Are you physically showing up to people’s offices?

I went to Boston. Richard Farina and Carolyn Hester were married at that time, and they were playing Springfield, Massachusetts, and then Boston. I went with them and I brought this little cassette and I played it for people. Philadelphia, I may have sent the cassette, or I may have gone down there when David was playing Philadelphia.

Everybody said, “Go away,” and so I went away. He did not come across well yet on tape. I was able to get him gigs in a couple of bars in New Jersey. I haven’t a clue how I did that.

Was it a proper show you recorded the Gaslight tape at?

It was a show; there was an audience. I think it was an evening that we set up as a booking, but I honestly wouldn’t swear to it.

There are six songs on the tape. Was that his typical repertoire around the time?

Yes, it was. Dave came on and did the chorus of “Car, Car.”

It’s funny that everyone’s passing on this tape because all these years later it’s so beloved and famous among Dylan fans.

Back then, no one was interested

It’s got “Song to Woody” on it, which I think a lot of people consider his first major composition. The movie treats it that way.

I think the tape is very good for what it is and the sounds on it. I have the original tape which will go up for auction one of these days. The sound is stunning. Because it’s such an old tape, I thought the sound would’ve dissolved, but it’s incredible. It’s just gorgeous.

It’s amazing that it’s held up so long.

I was shocked.

Does it sound better than the circulating version that leaked?

Yes. Absolutely. The sound is just incredible on this, and the sound on the bootlegged ones is dreadful. It’s not clear at all.

I didn’t even know it was bootlegged. I wasn’t going to walk around with a huge reel-to-reel tape, so I took it to a studio to have a small cassette made. I said to them, the same thing I always said to everybody, “Don’t make a copy.” But I’m talking in the wind and they did whatever they did. This is my assumption that that’s where the bootleg came from. I don’t know.

You said that with Dave, being a manager started as really booking agent. Was that what your job primarily was with Dylan also? Basically just getting him live gigs outside of New York?

Yes. It was very, very difficult. I got him very few. The major one is in the Caffe Lena in Saratoga. The story behind that was David was one of the first people to work in Saratoga, which is a wonderful coffeehouse. When it opened, it was one of the first out-of-town places to book folk music.

It’s still there I think. I was in Saratoga last year.

It’s still there. It’s a not-for-profit organization. A wonderful, wonderful place.

At that time it was new, and occasionally the owner [Lena Spencer] would not have a performer for the weekend. She would call me. I would hustle around and find her somebody at the last minute. When I asked her to book Bob, she listened to the tape, and she said, “He doesn’t sound good. Nobody will know who he is, and he will bomb.” I said, “I’ve done you a lot of favors, and now I want one. This is the one that I want.”

She hired him, and he bombed. The audience just did not listen at all. They talked through his set. At the end of the engagement, Lena called me and said, “You got your favor. Don’t ever ask me for another one.”

Less than a year later, of course, she brought Bob back. Now the club boasts that it was Bob’s first out-of-town engagement, which it was. That’s the way life goes.

In Chronicles, Dylan mentions that you got him a number of other gigs, and I wanted to know if you remembered any of these. He lists four places: Elizabeth, New Jersey; Hartford; Pittsburgh; Montreal.

That’s nice. I don’t remember. I really don’t. I probably did.

Were you able to leverage Dave as the more famous performer to get Bob in the door?

No. Dave was not famous enough to do that. [laughs] It wasn’t like Albert Grossman saying, “Oh, you want Peter, Paul, and Mary? Hire Bob Dylan.”

Since you mentioned them, it was almost Peter, Dave, and Mary. When Grossman put together the trio, he asked Dave to be the third.

Or it could have been Peter, Logan, and Mary. Logan English was asked. Who else? There was a third person Albert asked.

Honestly, I don’t know how serious he was about Dave. David was not right for that group. Not at all. Dave would’ve died in that group, and the group would’ve died. It wouldn’t have worked.

When you were managing Dylan, did it basically stay at the booking agent level?

It was only for about six months. It never got beyond that really.

After six months is when Albert Grossman swoops in?

Yes. Which, professionally, was a great move. My reaction was, “Oh, Albert can do so much more for you than I can,” which was true. My problem was that Bob told me after the fact.

If he had said, “Albert wants to sign me,” I would’ve said, “Great, how wonderful.” To tell me, “Albert wants to sign me,” and I say, “How wonderful,” and then he says, “I [already] signed with him”—it was a little rude. I thought it was bad manners professionally.

Is this happening after the famous Robert Shelton review and after John Hammond is interested?

It was after the Shelton review. I think it was before the John Hammond thing. He did not yet have a recording contract.

One other person I want to talk more about was Suze Rotolo. I know you two were close for years, long after the '60s even.

What they did to Suze [in the movie] is disgusting.

How so?

First of all, they collapsed the Bob, Suze, Joan Baez relationships so that they overlapped in a way that didn’t happen.

You mean in terms of, Suze goes away, he immediately cheats on her with Joan?

That didn’t happen. That did not happen. I don’t know exactly when Bob and Joan got together, but it was a good deal later, and it had nothing to do with Bob and Suze’s breaking up. Joan Baez did not come running down to New York to pop into bed with Bob every time Suze left town. It’s bullshit.

They used the name Sylvie in the movie. That is supposed to be Suze. When he meets her, they have him meeting a young woman who looks like an intelligent, active, involved person. She says, “This is my schedule. I do X, Y, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah on Monday, Tuesday.”

“I’m doing CORE on Thursdays, and I’m painting—”

What is CORE? They at least have the brains to have her define CORE. [It’s the Congress of Racial Equality]. CORE is never mentioned again.

After that, just about almost every time Suze is shown, she is shown sobbing, looking unhappy, mournful, looking at Bob longingly. That wasn’t real. They had fun, they hung out together, she taught him stuff.

I am not saying that he learned everything he knew from her, but she came from an intellectually astute family. Her mother was a Communist. Her older sister worked for mostly not-for-profit theatrical producers. Suze introduced Bob to certain poetry. She introduced him to Bertolt Brecht. She took him to art museums, which he had no background in. He wasn’t stupid, but there were things that he just didn’t have any background in, and she did. She turned him onto them.

She was involved with the Civil Rights Movement. She was an artist. She later did a lot of book art. She did not spend her time looking at Bob longingly saying, “Who are you?” It’s portraying a soppy woman. Suze was an intelligent, young, active woman. She had a life other than her life with Bob. The movie is just totally, completely inaccurate and misleading about the kind of person she is. It portrays her dreadfully. She was not at Newport in ’64 or ’65. They had broken up a long time before that.

This isn’t the history of somebody that I’ve read about. This was a good friend. We remained good friends until she died. I object to what they did because they misrepresent people’s personalities, actions. They turn them into different kinds of people from the kinds of people that they really are.

All of the stuff about Bob being a shapeshifter—which he was—within six months, we knew who he was. They have Suze saying to him, “I don’t know who you are. I don’t know your history. You know mine.” By then, she knew his history. We all knew his history. We knew it fairly early.

You mean the truth, not “I was in a carnival in Gallup New Mexico.”

Yes. Who he was, where he grew up. This whole thing about, “I don’t know who your parents are”—she knew who his parents were. Everybody did. We knew he had a background in rock music. We knew that he adored Little Richard. We thought he had very good taste in adoring Little Richard. Peter Stampfel knew that when he first met Bob. He heard him and he said, “This guy comes from a rock background.”

Last movie question. We’ve talked about a number of other performances, but not the big one. In terms of especially that early era, did you feel like Timothée Chalamet gave a good portrayal of Bob? Did you recognize the guy on screen as the person you knew?

I think he did a wonderful job. I really do. I think he caught the essence of the guy he was playing.

I will give you another quibble of mine. Pete Seeger I think is portrayed so self-righteously. I think that’s really overdone. I think it’s a brilliant portrayal [by Ed Norton], but his relationship with Bob is somewhat overdone. It was not that strong.

My impression was they combined a lot of the folk figures that preceded Bob into Pete Seeger. As opposed to having 10 or 20 folk-elder type characters, they just made it all one, who, while important in Bob’s story, is maybe not as important in the way they portray it.

It’s grossly, grossly exaggerated. I think they turned Pete into a folk music self-righteous person, much more so than he really was, and gave him much more of a relationship with Dylan than he really had.

There is a scene in which he has a PBS TV show. Bob is supposed to be on it, but for some reason, they think he’s not going to make it. Pete has on it, as a replacement, a Black blues singer who is sitting with a pint in a paper bag swigging on camera at the table and mumbling and boasting. That was disgusting. That was pandering to I-don’t-know-whose image of a blues singer who was discovered down south. That was a time when people like Dick Waterman and others were going down south and finding people like John Hurt and Skip James and bringing them back north. I will not use the word racist, but it was somebody’s image of what those musicians might have been like, and it was disgusting. It really was.

Why did they do that? What were they trying to show? The blues singers who came up from down south, or who had been in New York, like Brownie McGhee or Sonny Terry or Gary Davis, who was a gospel singer, when they went on a television show, they did not come on swigging booze. They came on like professional musicians, and they played and sang their music like anybody else.

You said that you felt that Timothée Chalamet caught the essence of Bob Dylan back then. Was there a particular scene or moment in the film where you felt that?

I don’t know why, but when he meets Bobby Neuwirth, I felt it. What Neuwirth is doing fits in so neatly with what he’s looking for. They wound up working together and became very good friends.

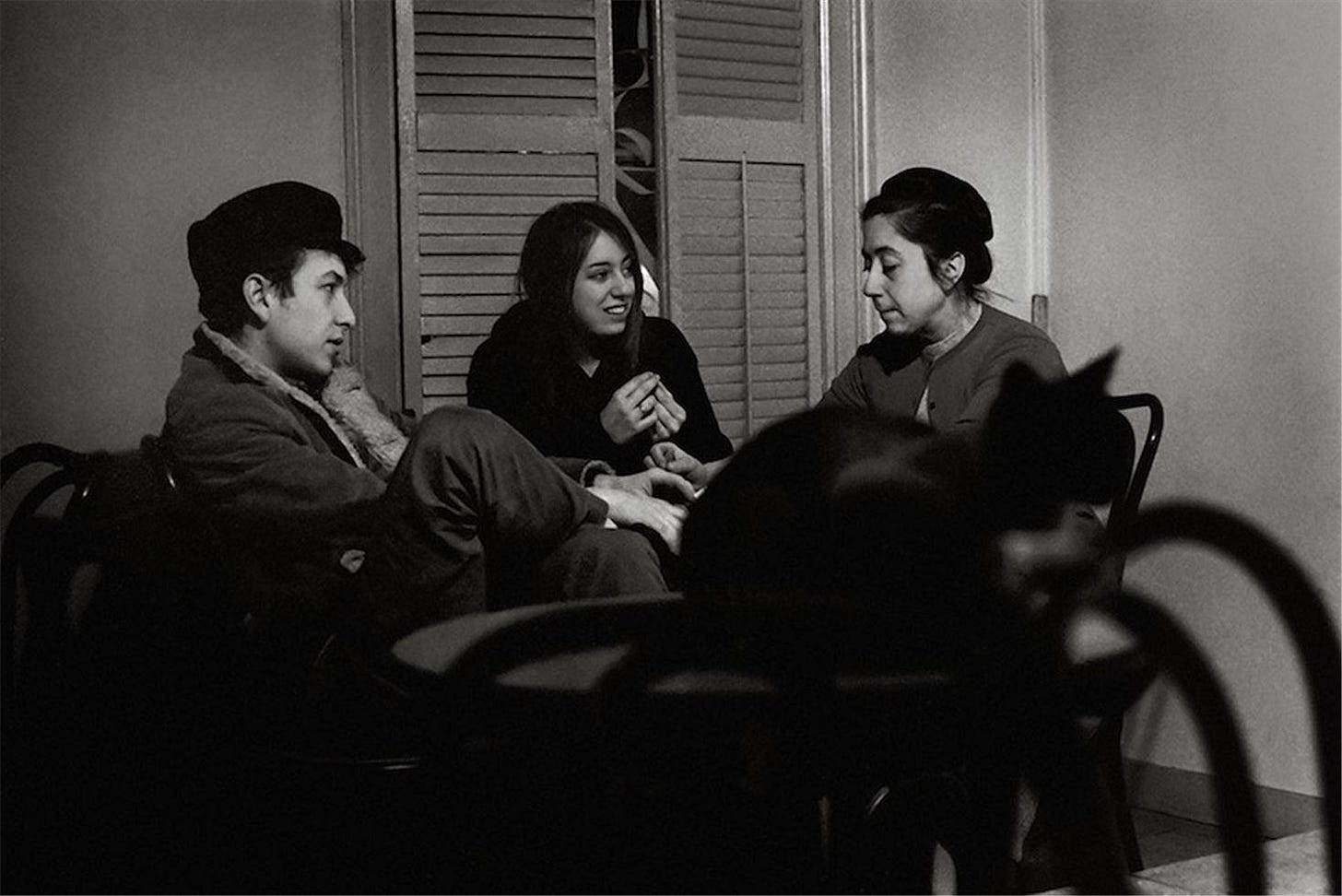

What else can you say about Dave and Bob’s relationship in those early years? Bob was crashing at your apartment all the time.

For a while, Bob was around. We were all very good friends. Dave and he were closer. They were both musicians; they were both guys. He seemed for a very short time to have a slight hero-worship thing of Dave, which wouldn’t be surprising. It’s hard to think, “Well, Dave was older.” In 1961, Dave was 23 years old. An old man. [laughs]

Dave seemed more grown up, I think. Dave really knew a lot. Dave was incredibly smart and incredibly well-read. I don’t know where the hell he got it, incidentally, because he was thrown out of high school when he was 16. He never went to college, but he had an incredible literary background. He read anthropology just because he was interested in it. He knew history. He knew jazz.

A genre you say Dylan seemed less interested in, when you two would play jazz records in the apartment.

Yes. At that time, Bob was less interested.

One of the things that Bob had, and I didn’t realize this until a couple years ago, Bob had and still has, I presume, a kind of odd ability to take in information. He can retain the parts of it that he wants, discard the parts of it that he doesn’t want, and tuck away parts of it for future use. Which most people, I think, can’t do. They lose it. They don’t remember it. If they want it, they can’t pull it out. He can.

Are you thinking that jazz might have been in the tuck-away-for-future-use category?

Yes, I am.

He was doing Sinatra covers records, and even his own compositions in the last 20 years, many of them have been quite jazzy. This is decades after he was in your and Dave’s apartment.

He’s had a lot of time. He’s worked with a lot of musicians. You got to realize all those backup studio people, a lot of them have been jazz guys. They work with everybody.

Jim Keltner, who he’s worked with musically for longer than anyone, started as a jazz guy.

Even in the folk world, people like Bill Lee, who did backup for some of the groups back in the '60s. Nobody really thought anything of it back then.

Since we’re talking about backup musicians, do you feel the hostility that is generally portrayed from the folk world that “Dylan went electric”—not just in the movie, but really is always part of the story—do you feel that was accurate, or is that overstated?

It’s overstated. It’s really exaggerated. There was a touch of, “Oh, my God, look at what this guy has done.” There was a fair amount of that. Dave and I were there and we said, “Oh, okay. Interesting.” I mean, shocked? We weren’t shocked. We weren’t purists. Neuwirth had had electric groups. Obviously, the movie had to exaggerate the reaction because that’s partly what the movie was all about. He came from here, he went here, he left here. There was an element of upset in the folk community, but not like that.

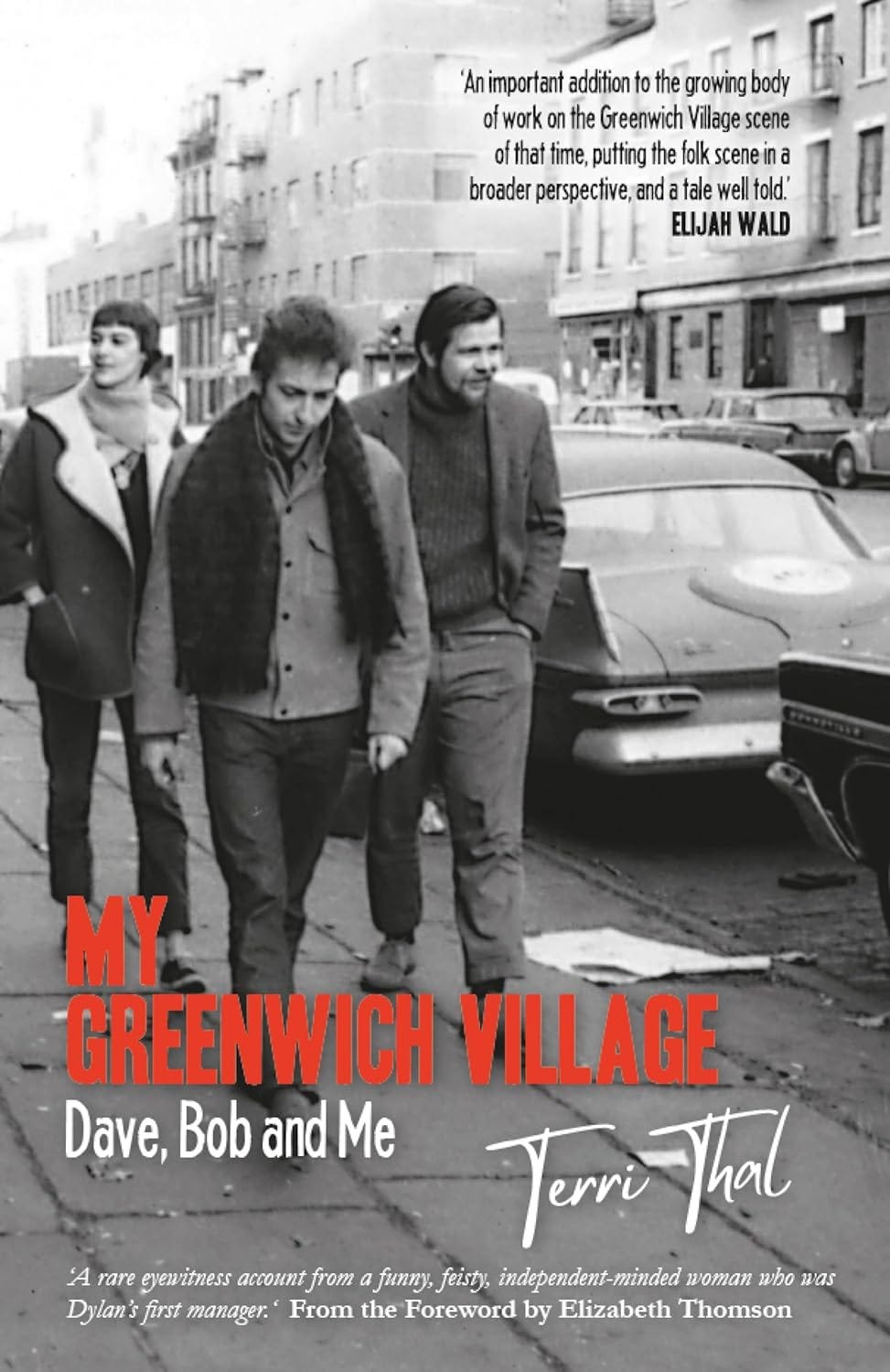

I wanted to ask about the photo on the cover of the book: you, Dave, Bob, and Suze walking down the street. The famous photo, although it’s actually photos, plural. There’s a few of them.

It’s a whole contact sheet. There must be 30 or 40 pictures in that shoot, which I hadn’t realized for years.

What was it for, do you remember? A newspaper article?

I don’t know. Jim Marshall, who became a very famous rock photographer, was new to rock photography at that time. We all went out to breakfast, and that’s what happened. He took pictures.

Including the woman on the left who some people think is Karen Dalton.

It was not Karen Dalton. I have no idea who she was.

The one thing that bothers me is that Suze was cropped out of the picture. I objected to that.

You mean on the cover of your book?

Yes. The designer said that another person simply made the photo too wide. Eventually I acceded.

A few years after the motorcycle crash, after you’ve lost touch, after you and Dave have separated, Bob visits you in your apartment. You felt he was reconnecting to his roots.

By that point, I’d stopped managing. It was not my world anymore. The world had just changed. I guess I had changed. The Village was full of hippies and beatniks and dope. It wasn’t the folk music thing that I knew.

Are we talking late '60s?

We’re talking late '60s into the early '70s. I’d walk down the street and there were kids with vapid eyes. The folk singers were traveling by then; the Village was not a hangout for the folk singers the way it had been. People were working out of town. It wasn’t home anymore as it once had been. What had happened to the folk world was becoming very commercial, and I didn’t want that.

Bob had disappeared into another world years before. At some point, he came to visit. I think he was visiting a lot of people from his past. I was one of them.

What happened at that visit when he swung by?

Nothing terribly much. We just talked a little about the old days.

Thanks to Terri Thal for taking the time to talk! Pick up ‘My Greenwich Village: Dave, Bob and Me’ at Amazon or wherever books are sold.

great interview Ray

Thanks Ray, you just filled in another piece of Bob’s life.