30 Years Ago Today, Bob Dylan Sang with a 64-Piece Japanese Orchestra

An interview with 'Great Music Experience' EP Tony Hollingsworth

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

“I'm used to measuring my audiences in hundreds of millions,” Tony Hollingsworth jokes. When the British entertainment super-producer puts together a show, he goes big. Really big. He’s produced nine of the world’s largest global broadcasts outside of sports. His two celebrations of Nelson Mandela at Wembley Stadium were broadcast to over 500 million people apiece. His staging with Roger Waters of The Wall at the site of the recently-fallen Berlin Wall aired on TV in 100 different countries.

And, in 1994, he booked Bob Dylan for another one of his television spectaculars.

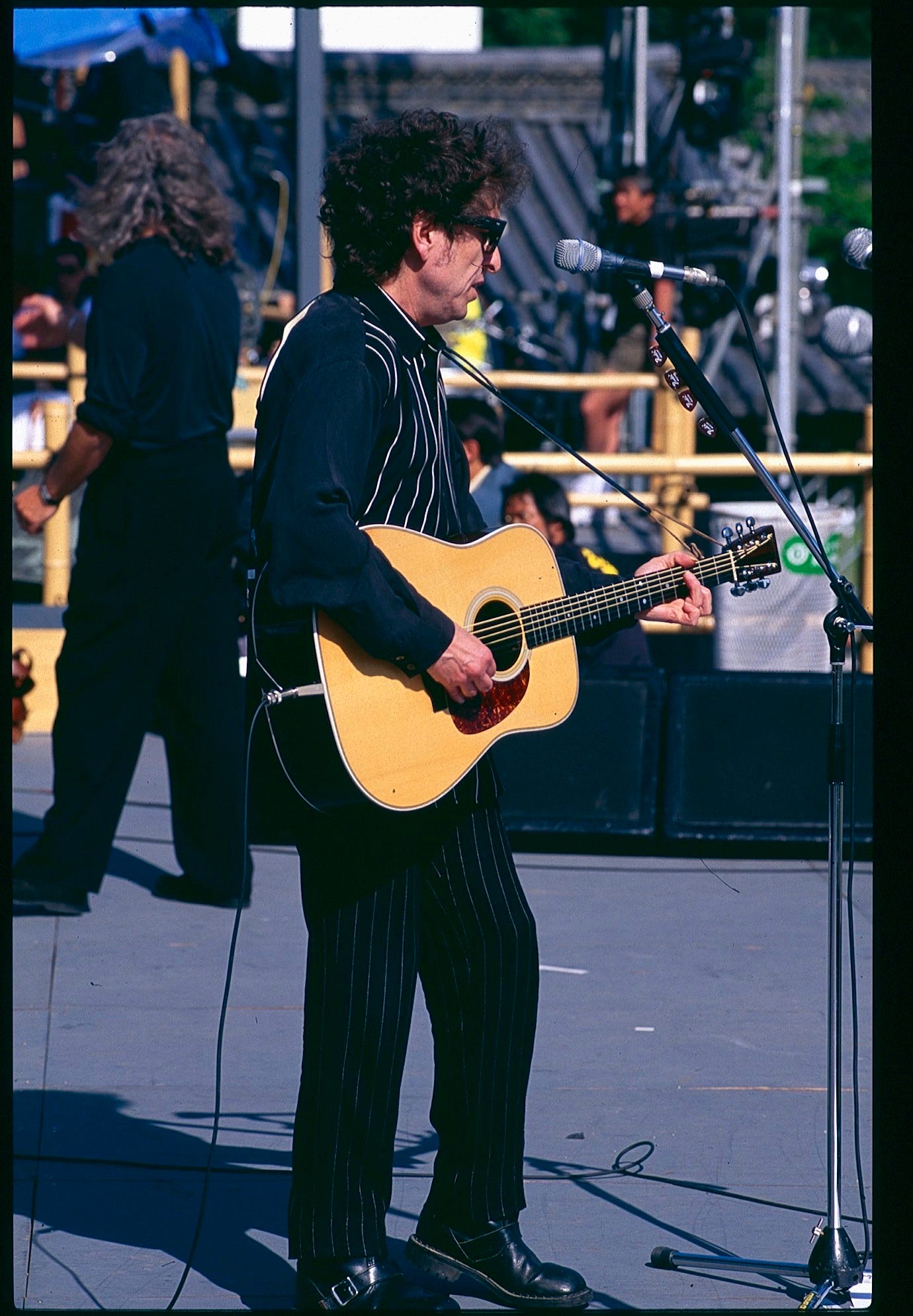

If you’re a big Dylan fan, you might have seen the YouTube clips of Bob singing with an enormous Japanese orchestra. This is, as best I can tell, the only time Dylan has ever performed with an orchestra—a 64-piece orchestra, no less, alongside musicians playing replicas of eighth-century instruments. He sang three songs: “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall,” “I Shall Be Released,” and “Ring Them Bells” (then reprised “Released” in an all-star finale).

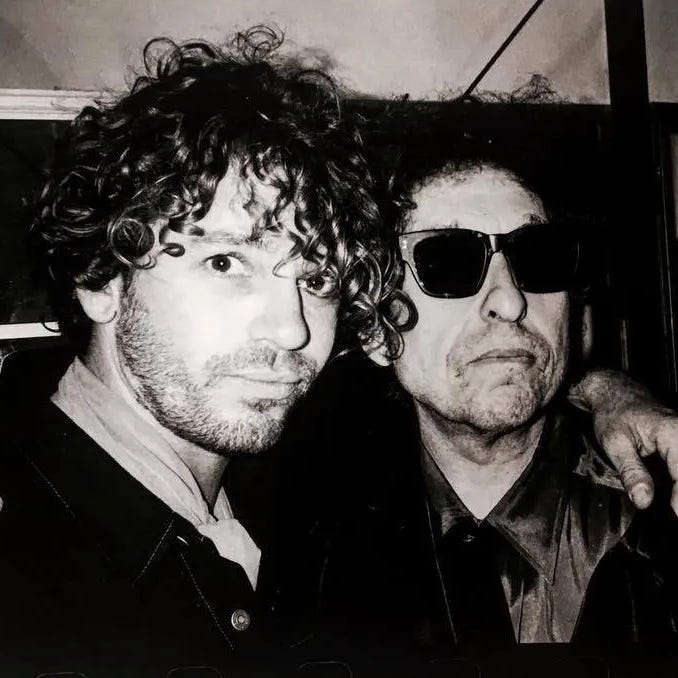

I’d seen the YouTube clips, but I didn’t really know what the context for them was. So, in anticipation of the 30th anniversary today, I called up Tony (pictured below) to talk me through it.

The event was called The Great Music Experience, a global broadcast from an ancient Buddhist temple in the city of Nara, Japan. It paired Western stars (Bon Jovi, Joni Mitchell, INXS, etc) with Japanese musicians, aiming to use the appeal of rock stars to broaden the audience for the world’s cultural heritage. There were three shows, May 20, 21, and 22, with the final night being broadcast. The Japan shows were supposed to be the first of a series of events around the world—but, due to some bad luck involving Mexican currency collapsing, it turned out to be a one-off.

I’ll let Tony Hollingsworth explain more—but, first, here’s a version of one of the songs Tony sent that’s better quality than the VHS rips on YouTube:

Before we get into anything Dylan specific - for people like me who don't have much real context for where these Dylan-with-orchestra videos come from, can you explain the idea behind the event?

I've always been interested in musical combinations of different cultures. I started exploring the idea of doing something with the backing of UNESCO—the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. The idea was to pair internationally-known musicians, which tended to be Western, with different cultures. The first one was to happen in Japan. Then we were meant to be going on to do one in Mexico, but unfortunately the peso crashed and took the bottom out of that one. So we didn't get to our second.

I'd been to Japan a number of times and decided it would really be good to use Tōdai-ji, which is in Nara and is the largest wooden building in the world, containing one of the largest statues of Buddha. Although it's been rebuilt a number of times, it was first built in the eighth century. UNESCO's main role was to help us secure a really wonderful cultural heritage site, so I asked if they would help us secure that with the monks running it.

The notion was to put together a variety of internationally known musicians, which turned out to be Bob Dylan, Ry Cooder, Joni Mitchell, The Chieftains, INXS, Jon Bon Jovi, Wayne Shorter, and put them in combination with musicians from the place that we were in: Japan. So Ry Cooder performed with an Okinawan garage-folk band. Joni Mitchell appeared with rock-and-roll guitarist Hotei, who's still a big rock star out there, and with Ryu Hongjun, who had his sixth-century-style ensemble of classical instruments. In fact, all the instruments being performed in that ensemble are replicas of instruments found unearthed from the sixth century in the back of the temple.

You mean the musicians playing with Joni specifically are using the sixth-century replicas?

And the bells part of it, which you can see in “Ring Them Bells” in Bob Dylan's set. Plus there are other bits in performances. The Chieftains did quite a lot of combinations with that orchestra. INXS did a wonderful combination on one of their songs, where it starts very rock and roll and slowly transfers and ends up with the same tune being played on sixth century Japanese instruments.

Then there was also the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra as well.

That's the one that Dylan performed with?

Yeah.

But at the beginning of all of this, I was putting together the team before I put the musicians together. I wanted the audio to be looked after very, very carefully, so I went and recruited a young man called Sir George Martin to be my audio man and to be the godfather over the rehearsals and the arrangements.

In those days, because you didn't have programmable desks, there were 149 channels of sound coming off the stage. You had to have three engineers to adjust the levels for each track. One of which was Sir George and the other one was his young son at the time, Giles Martin.

Who now oversees all those Beatles remasters.

Giles cut his teeth there at the Great Music Experience. In the evenings when I was still working away, he was able to go out drinking with the bands and got on with the INXS guys. They asked him to come and mix their greatest hits. That was his first album project.

I also wanted to put this orchestral element into the project, so I wanted to bring in an arranger, an orchestrator, to help. Because I knew Michael Kamen from the Wall event in Berlin, I went to see Michael. He said, “Sounds really interesting. What's it called again?”

At this point in time, it was called The Great Music Experiment. But it became The Great Music Experience. The reason for that was, as I was trying to pull together the different elements that make these things happen in Japan, we weren't getting anywhere with the investors and sponsors.

We then had a very long session with my co-producer out in Japan, Yoshimeki-san, to try and work out what was wrong. We realized that it was the word “experiment.” For Western culture, the idea of doing something new, unique and different, and displaying it to the world, is wonderful. But the idea in Japan that you might “experiment” and broadcast your experiment to the world is such a stupid thing to do. It's just profoundly daft.

No one wanted to put money towards an “experiment.”

So we changed “experiment” to “experience,” and then we could sell it.

Anyway, he said, “I’d love to be involved, but it's called ‘great music,’ Tony. We should have some great music in it.” I said, “Michael, that's what I'm asking you to produce: some great music.” He said, “Yeah, but great music. I mean [music by] Bob Dylan or somebody of that stature.”

A few months later, I was able to go back to Michael Kamen and say, “Michael, you've got to do the overture. You've got to do this. You've got to do that. You've also got to do three songs, which are Bob Dylan songs.”

And he said, “Great. Who am I doing them with?” I said, “Bob Dylan.” “Really?”

It was the first time [Bob] had ever worked with an orchestra. He was interested to see what it was like.

So how do you convince Bob Dylan? What's the pitch? As I'm sure you know, he doesn't do this sort of thing very often.

Well, I already knew them because Bob had already performed at Guitar Legends [1991 festival in Spain with a bunch of superstar guitarists], which I put together.

I didn't realize you were behind that. I interviewed Richard Thompson and we talked about the two of them doing their sort of impromptu duets.

And really, that didn't go so well.

In what way?

Well, they performed together, but it was a busk. The main bit of my productions is that they're really, really well rehearsed and arranged. And Richard Thompson and Bob Dylan were just making it up. Bob hadn't come in early enough to do the arrangements and the rehearsal. Richard had.

With these musicians, they've had it really easy. Quite recently, I watched a little bit of footage of Paul McCartney and Neil Young on stage somewhere. I can't remember whose show it was, but one of them invited the other one on, and they try and work it out on stage. And it's a really special moment for the audience, but it's usually terrible musicianship. They're just busking.

Anyway, that's what had happened there really. Bob had turned up too late for the music director of the set to be able to bring something together that was special.

So I already know Bob and [manager] Jeff Kramer, and I put it to them. The idea that by then Joni Mitchell and Ry Cooder had also said yes, it was making him feel, “Well, I like them. I'm in good hands here.” And then I was pitching the idea of, could we orchestrate some songs?

He was comfortable with the idea that George Martin was around looking after the audio and there to help with the orchestration. It was a very comfortable sort of setup really. And [longtime collaborator] Jim Keltner on drums. Because it wasn't just an orchestra, as you've seen, it was an orchestra and a little backing band, and he could see that the backing band was fantastic too.

The idea that you call these things “backing bands” is really terrible. There must be another word for it. To call them a “session band” is horrible. To call them a “house band” is horrible. On one of my shows, Songs & Visions, I decided to give them a name. They were all really expensive session musicians, a band that you couldn't afford to take on the road, so I called them The Unaffordables.

Anyway, once we'd done the booking and everything else, we come to the detailed arrangements of when he's going to fly in, how many days he'll be in Japan, and getting him into the rehearsal studios. We were rehearsing in Osaka. It takes about 45 minutes to drive there because the traffic’s so bad. I said to Jeff Kramer, “I'm going to have him start his first rehearsal session at nine o'clock in the morning in the studio.” And Kramer said, “You must be out of your mind. Bob Dylan has never, ever gone to anything at nine o'clock in the morning.”

I said, “He will.” He said, “What the––? No, he won’t!” I said, “He will. He'll be so jet lagged, he’ll have been up so bloody long, he’ll think it's three o'clock in the afternoon.”

Did it work?

He was there dead on time. Walked into the rehearsal studio, and I happened to be there at the time, so I greeted him and said, “Tea or coffee?” “Tea.” So he had tea.

By the time Bob Dylan arrives at the rehearsal studio, is there a full orchestral arrangement? Are they basically ready for him to just stand there and sing?

Michael by then had created a full arrangement. So it was a matter of playing these with Bob and seeing what he thought, seeing if there needed to be adjustments at all.

Were there any adjustments?

I wasn't sitting in those sessions holding their hands. I was basically putting people together and getting onto the next bit—you know, dealing with broadcasters or whatever. I think there were adjustments because Michael told me that, but whether it was Michael suggesting them or Bob, I don't know.

The big difference was that they weren't following him.

We did the show over three nights. Three times. At the end of the third night, when he came off, he said to me that was the best he'd sung for 15 years. I don't know whether that's true, but that's what he said to me. He had no reason to say it, you know? I didn't say, “Was that the best you'd sung for 15 years?” He just happened to say it to me.

The next day, before he left, I asked him, “Why was it?” And he said, “Because all my life, people have been following me. In this case, Michael was conducting. I had to fall in line.” He said it was completely liberating. “I was playing along with them, because they were going.” You know, an orchestra doesn't wait for you.

They're not going to turn on a dime if he adds an extra measure or beat or something, like his band might.

Exactly. If you drop a verse, the whole thing's fucked. Unlike with the bands and other session musicians who followed him.

That also explained then why at another point, he’s checking the lyrics that are written on the card that’s stuck on the front of the stage, which was his request. He said, “I want the lyrics written down.” Because I think he sometimes misses out a verse. He wanted the words written down on the front of the stage just in case.

There's a music theory book about Dylan coming out at some point, and the writer Steven Rings argues that the performance of “Hard Rain” there changed how Dylan performed the song ever after. Basically, it reconnected him with the melody. He took the lessons of singing with an orchestra back to his small combos.

Yeah, exactly. What Michael Kamen was looking for all the time is melody, and versions of melody to build on.

Do you remember who picked the three songs he did?

I think that was Bob's team. That was all discussed beforehand, because Michael had to get into making the arrangement.

How about the all-star finale, “I Shall Be Released”?

I asked Michael Kamen and George Martin to suggest a song for the finale and to work on an arrangement. Michael suggest that they did a Beatles song, “Hey Jude”. George thought it inappropriate, but that “as Bob is here, we should do one of his songs.” They then discussed and came up with “I Shall Be Released” and worked on an arrangement and the sequence of stars, Japanese and Western, to sing the phrases.

What else do you remember from the show? Or shows plural, I guess. I think of it as one show because of the one video, but I know there were three.

We stage things nowadays three times. I arrange and rehearse things in studios for weeks beforehand, then put them on three times. Because if you're going to get all these guys together and you're going to go for a global broadcast, please get it right. Stop that Guitar Legends problem.

So what do I remember about Great Music Experience? This is perhaps a little longer an anecdote, but to get the monks to agree to us using their temple took a long, long time. I was going to Japan every month. With my co-producer [Kunihiko] Yoshimeki, we wrote [to the monks]. “We have the backing of UNESCO, but we're wishing to come and talk to you about it, see if we can use the temple.”

So a meeting was set up. Yoshimeki and myself were on one side of the room, sitting cross-legged on the floor. And on the other side of the space, a traditional Japanese space in which women in traditional Japanese dresses served tea, were five monks in traditional Japanese costume. Big long sleeves, white socked feet with the thumb space in it, bald or very closely shaved heads, etc.

The five of them were to ask questions of us, and we were to talk about it. But my co-producer Yoshimeki had said to me, “Tony, remember that in ancient Japanese culture, when you're talking, it's because there is a difference between the two of you, and you're trying to settle this difference. When there's silence, it's the sign of harmony. So if there are gaps, leave the gaps.”

I didn't find that hard because I was hopelessly jet lagged. The idea of being silent for a bit was sort of easy.

Anyway, we went to the first meeting. The first guy of the five asked questions about the physical plans, where we were going to position things: the stage, the trucks, all this sort of stuff. The second one asked about the commercialization of it, then the next one—et cetera, et cetera. They went through all these different stages.

This meeting went on for about two hours. Some of those gaps were two or three minutes long between questions. Gee, that's quite hard. It's a long time, two or three minutes when you're sitting across from people.

The fifth man on the opposite side was very old and was clearly the most senior monk. Two or three minutes after the fourth guy had asked his questions, the old guy, who I thought had been asleep during the whole of the meeting, woke up and clicked his fingers at Yoshimeki next to me. He said, in Japanese, “On how many countries’ TV will our temple be seen?”

I said, “Well, I can't promise anyone at the moment, but I expect we'll get up to about 60 broadcasters around the world.” And that was the end of the meeting. Everybody stood up, walked backwards out of the room, bowing.

A month later, we went back to have another round to progress it. Exactly the same people were in the meeting, in exactly the same positions, and they asked exactly the same questions.

Really?

The same questions, the same gaps, and at the end, the old guy woke up out of his slumber, clicked his fingers and said, in Japanese, “Yoshimeki, on how many broadcasters will our temple be seen?” At this point in time, I’d sold it to about 10 countries, so I said, “Well, at the moment, 10, but I expect to get to 60.”

End of meeting. Up we all get, walking backwards out of the room, bowing as we go.

Next one. Now I'm wanting an answer. But I'm not getting one. So I prompt Yoshimeki to talk to them and say, “Look, he's coming back, but we need an answer on whether we can do this.”

So we have another meeting and, again, exactly the same thing happens. The same people, the same clicking of fingers, but I could now say “20 [countries].”

Meeting’s finished. No conclusion to it still.

I come away and I say to Yoshimeki, “We’ve just got to get them to sign a piece of paper. I need it for the insurance…and I can't get the investment without the insurance…” All that sort of producer stuff.

He talks to them when I'm back in England. He says, “They want to have one more meeting. And if that meeting goes well, they'll give you the permission before you leave the temple.”

So we go back and do exactly the same meeting again. Exactly the same questions. I'm giving exactly the same answers, except to the question about the broadcasters. At the end, the old guy—80-odd years old, bald head, long sleeves, etc.—wakes up, clicks his fingers and says, “On how many countries will our temple be see?” And I say whatever we were up to at the time. 25, say.

Now this time, instead of everyone getting up, the old man goes back into this sort of meditative state. We sit there for a few minutes whilst he's in his meditative state, which looks a bit like sleep. [laughs] Then he perks up again, and clicks his fingers again. He says, “Now on how many countries…” Three minutes later, and he asks the question!

As a joke, in English, to Yoshimeki, I [look at my watch, as if the three minutes made a difference] and go, “Oh, by now?” The old guy laughs.

Wait a minute, he's not just got the joke, but does he understand English?

Remember he's cross-legged, so he then starts reaching down into his long, long sleeve, fumbling about to get something out of his long sleeve. He pulls out a packet of Marlboro Lights, lights up, and says, “You got it.”

I went away from that going, what was going on for the last four months? Yoshimeki explained, “You answered every question in exactly the same way, except for one, which was about the broadcasters. They just wanted to know that you were consistent. That you were in harmony. You weren't changing the story to speed it up; you weren't trying to be more impressive. It was exactly the same story each time.”

So we got it. We got the eighth century temple in Japan.

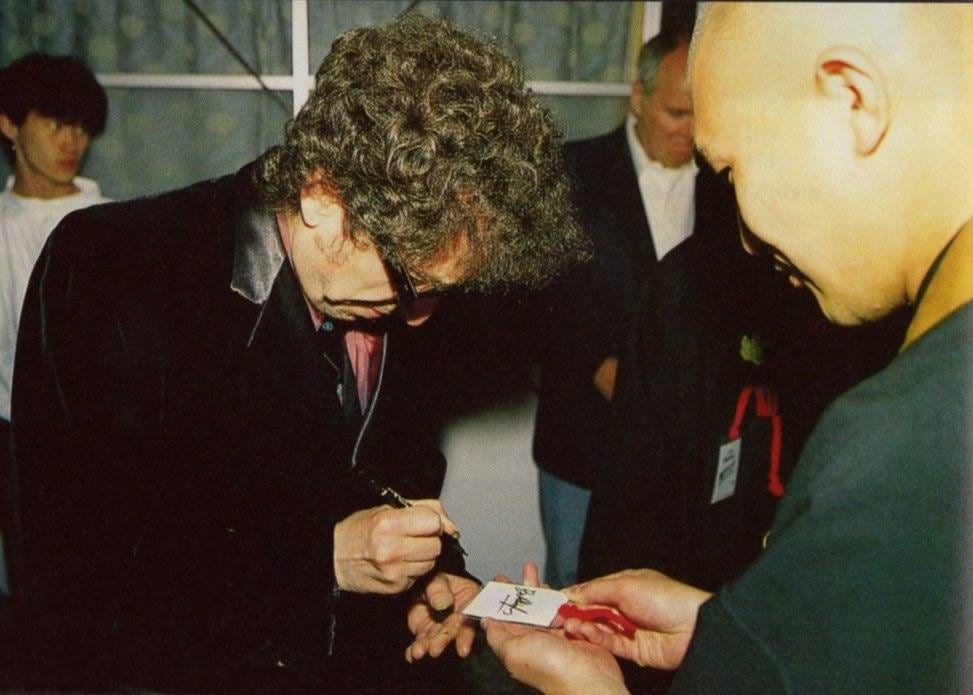

Speaking of the monks of, I saw photos of Dylan signing stuff for some of the younger monks afterwards, which I found fairly charming.

Yeah. We had two choirs of Buddhist monks helping us. One belonged to the temple itself. They were going to open with a chant. But it was a real problem because they wanted to chant facing the Buddha, which meant they would have had their backs to the audience. It was about a month’s worth of lobbying by me to get them to agree that they'd actually face the cameras.

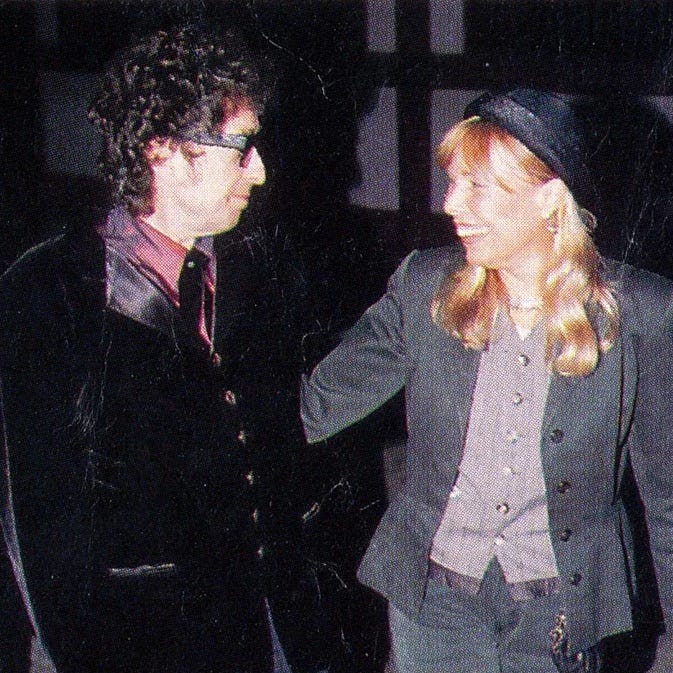

Any particular Joni Mitchell stories or memories? Just watched her video with the Japanese flute player.

That's Ryu Hongjun, the leader of the sixth century Japanese ensemble. Ryu Hongjun also has an uncredited role in The Last Emperor. It's a beautiful film and a wonderful score by Ryuichi Sakamoto and David Byrne. Ryuichi Sakamoto was the lead name, but Ryu Hongjun had given him a whole load of chord sequences, riffs, sections of it all. She performed also with Hotei as well. Hotei is a Japanese rock guitarist. It's a lovely piece as well.

Joni’s very interested in Buddhism, or at least was then, so she was interested to come and be around the monks. And with these artists, we didn't just ask them to come and rehearse and go. We set up little cultural trips as well. So they went up into the mountains, to other temples, to the theater.

Do you remember if Dylan did any of those?

I don't think so.

I was watching some of X Japan’s set, and the people in the crowd are going crazy for these younger local rock stars. Did they know who Bob Dylan was, or Joni Mitchell?

It was an interesting mixture really. Some in the audience obviously knew exactly who they were, and others had come for Hotei and X Japan and INXS and Jon Bon Jovi. Some would just have bought tickets for the whole nuttiness of it—the idea, the experience.

Another silly sort of cultural difference. In designing the ticketing of this event, I wanted people to stand. The local promoters came up and said, “We’ll divide the grass area up into squares. We’ll put on the ground a chalk marking of where the end of the square is and, in the middle of the square, a pole that says, in Japanese, the equivalent of A or B or C or D. If you've got a ticket with A on it, in Japanese, you go and stand in the square with A.”

I said, “What? No fences, no barriers? If you've got on your ticket [in the back section] H, you go and stand at the back, even though you're first in? Don't be stupid. They'll just go up to the front of the stage.” And they said, “No, no, no.”

I said, “I don't believe this is true.” They insisted it was.

Anyway, halfway through the first show, my production manager came and got me and said, “Let's go and look at the fire lanes.” And you've literally got chalk squares on the grass, and people are standing in the squares. If they're dancing and they step over the square, they go back.

This is incredibly different. It's just such a socially responsible way of behaving. The whole of Europe, the whole of America, almost every part of the world, you have to pen them in. You have to have security guards. Very different.

Were there big differences between the three nights?

I can't remember particularly Dylan's, but generally people just got better and better and better. You do it in a rehearsal studio, that's one thing, but to do it on a stage in front of an orchestra, with lights and sound and cameras, everybody's game is improved greatly—and then they improve on that. So the third night was the best of the nights.

Thanks Tony! Here’s video of the entire three-hour television broadcast. Dylan starts at 1:19:42, but it’s fun to click around and sample different bits to get a sense of the entire program.

1994-05-20-22, Great Music Experience, Nara, Japan

Coming up later this week: An interview with someone behind a DIFFERENT famous Dylan performance, two decades earlier. Subscribe to get it sent straight to your inbox.

Recent Posts ICYMI:

A Blood on the Tracks Three-Pack

This subscriber-requested show (shoutout Matt S) from Sioux City in 1994 features something I’ve never seen before: The first three songs off Blood on the Tracks played back-to-back-to-back. If Bob ever stooped to do one of those “play the full album on its anniversary” tours, he was off to a good start here. Well, almost; at this Sioux City show he pla…

Three Musicians Who Auditioned to Play with Bob Dylan (and Didn't Make the Cut)

With all the Dylan band members I’ve interviewed, one thing that comes up a lot is the strange audition process to join Bob’s band. For one, it’s rarely called an “audition.” As gospel-era guitarist Fred Tackett put it to me, “It’s just like, ‘Want to come down and jam?’”

Time Out of Mind on the Horizon

In April of 1997, the time of this subscriber-requested shout (shoutout John C), Bob Dylan was in the middle of a thrilling period of renewed inspiration. But no one knew it yet. Over the previous six months, he’d recorded all of Time Out of Mind. He wouldn’t announce its release until July though, so audiences at this Portland, Maine show were entirely…

thank you

This is amazing and I love the synergy of INXS playing their Subterranean Homesick Blues tribute on the same show Bob was at. Probably the only time that ever happened.