Bob Dylan Drummers Summit: Jim Keltner, Stan Lynch, Winston Watson

with guest host Jon Wurster!

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

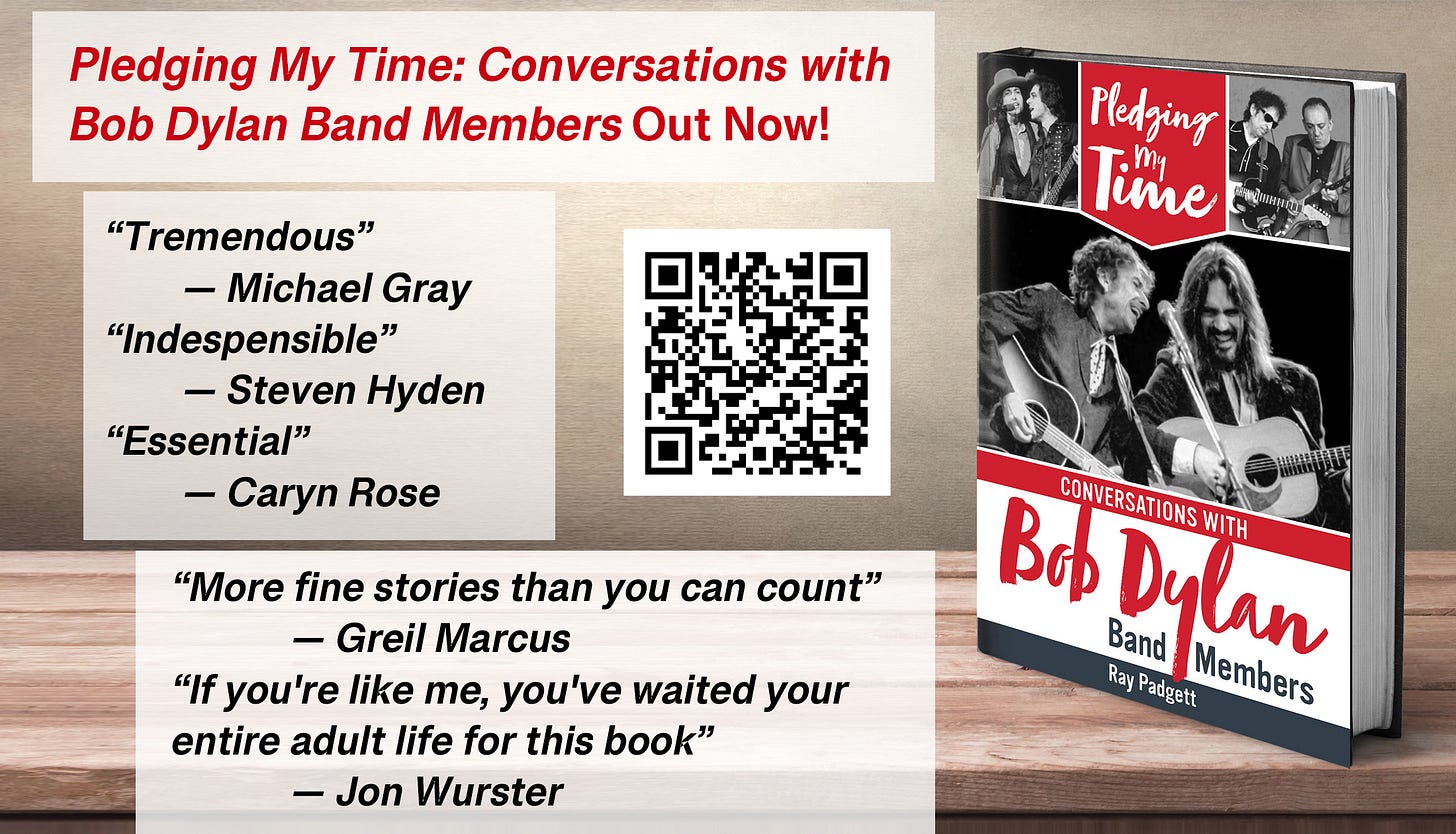

Last month, to celebrate the publication of my book Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members (available everywhere now!), I convened what I dubbed a “Dylan Drummers Summit.” In a private Zoom for the most generous supporters of the book’s initial crowdfunding campaign, I brought together three of the greatest drummers to ever play with Dylan (and three of the book’s best interviewees):

Jim Keltner, who has drummed for Bob across decades, starting with the Greatest Hits Vol II and “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” sessions in the early ‘70s through the gospel tours and any number of appearances since.

Stan Lynch, founding drummer of Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers, who backed Dylan throughout 1986 and 1987.

Winston Watson, drummer for four years in the ‘90s Never Ending Tour, including iconic appearances on MTV Unplugged, Woodstock ‘94, and more.

Now the video is available for everyone, above. The conversation was charming, funny, engaging, and at times quite moving as the three of them reflected on their time with Dylan and enjoyed each other’s (virtual) company.

Since I’d already talked at length to all three of these gentlemen for the book, I invited a guest host to join us: Jon Wurster, drummer for Bob Mould and The Mountain Goats and comedian on The Best Show. In the first part of the conversation, Jon asked his three fellow drummers some incisive questions, and then in the second half, I opened it up to the fans in the Zoom to jump in with questions of their own.

I’ve included a lightly edited and condensed transcript below as well, but — and as a writer, I can’t believe I’m saying this — I’d honestly recommend just watching the video. These are three extremely engaging storytellers, and half the fun is watching/hearing them share their memories in their own voices. But, if you’re not somewhere you can easily watch a video, a readable version is below.

Huge thanks to Jim, Stan, Winston, and Jon, as well as everyone who supported the book back when it was just a wild idea I had! And if you haven’t picked it up yet, maybe one of these quotes will convince you (longer versions of them all plus more on the Amazon page):

Dylan Drummers Summit

Jon: Jim, you've had a 50-plus year working relationship and friendship with Bob, and I wanted to go back to your first session, 1971, “Watching the River Flow.” What were your first and impressions of him as a human, but also as a musician?

Jim: Leon [Russell] called. I said, "Bob Dylan? Yeah, okay.” The next thing I knew, my favorite rhythm section at that time, Carl Dean Radle on bass, Jesse Ed Davis on guitar, and, Leon— you couldn't do anything wrong when you're playing with him.

Bob never said a word to me, but he talked to Leon. I figured, okay, he's Bob Dylan, he's not going to be like a guy with a lot of small talk and stuff. So I kind of expected that. Then we started playing. I saw him standing against the wall and he was writing lyrics while we were playing.

Like I said, you couldn't do anything wrong with Leon, and then with one of Bob's songs and his singing… His voice was different in those days, but it was incredible. I fell in love with the whole situation right away. Then I said something stupid to Bob.

Stan: [laughs]

Jon: What was it?

Jim: Stan appreciates this. Fortunately I don't do this anymore, because I had to learn a few hard lessons, but I felt, if things are quiet for a minute, don't let things be quiet. Say something. I looked at Bob and I said "Hey, I hear you have seven children."

Stan: Oh, great…

Jim: I didn't even get a look, [much less an] answer. So I thought, "Okay, I shouldn't have said that. Why didn't I say anything else?"

Anyway it was an amazing experience. You can only imagine. You guys have played with Bob, so you know what it's like. There's the highs and then the lows, and even the lows— they're low to you because of your expectation for yourself, but generally with Bob, he's one of those kind of artists, you can't go wrong. It's hard to screw it up. If he's there and you're here, all you gotta do is try to be in the middle of it somehow. I know you guys know what I'm talking about.

Jon: That leads me to a question for Stan. I think the tour that Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers did with Bob in ‘86 was the first tour he'd done with a self-contained band since the tour with The Band in ‘74. I was wondering what the dynamic was, with this legendary dude coming into this band that's its own biosphere and has a lot of hit records and success. Who’s adapting to who?

Stan: Boy, I think it was a glorious free for all. If anybody here has been in a band, you know that dynamic is an ebb and flow, always. It's always coming and going. You're always sort of breaking up and you're always in love. When Bob came into the picture, we were invited I think by [shared manager] Elliot Roberts. "Would you guys like to maybe play a show with Bob?”

We all showed up at rehearsal. I don't know if our band was really even getting along as a band. We were probably in some strange place. I got to bring up Benmont [Tench] because I just love him, and he was my north star always in that whole experience. He was very reverent about Bob. I was young and dumb. I knew “All Along the Watchtower”—by Jimi Hendrix. That's how dumb I was. Ben cribbed me, and he said, "These are probably the songs you're going to want to really take stock of.” So when we showed up, the dynamic was really just five guys feeling up an elephant. Like, what do you got? “I got a tail, I got a head, I got an ear…”

To me, it was just wonderful chaos. He can do it without you and he'll be fine, so your job, or my job, was to find a way in with my guys, with my posse, to support him and also let him know how much love there was. I was still at that point in my life where every four bars, I had to do something stupid. That was my way of showing "Hey, I'm really in this."

Bob, at one point in the first rehearsal, he was getting into it. Like he was striking shapes and being a rock star. He turned around and he raced up the riser and came right into my face. I thought, “Oh, this is it. This is where I get fired.” I remember the blue shirt he was wearing; I remember the sunglasses. He leaned into me very close and intimately, and his first words to me were really beautiful. He said, "I love what you're doing. I love what you're doing." At that point, you're kind of going, well, this could either be his way of saying [makes screw-you gesture], but I really believed he enjoyed that I was so animated. I was so excited to be there that I was reacting to everything. I was in heaven.

It was all 13-bar blues, you know? It all happened when Bob decides to step to the microphone. There's no math. You can't count this. You just got to be in it, man. Those four or five minutes when we were playing, you levitate if you get it right. It was the coolest. It was really the high point for me as a drummer. It kind of went off a cliff after that. It was the last of the real playing, flying by the seat of your pants.

Jon: Winston, you have what I think is the greatest entrance story into the major leagues of rock and roll of anyone. You're at home out west. It's the fall of '91. You get a call from Charlie Quintana, who was playing drums with Ian Wallace in the Bob Dylan band. He wants you to fly out to Kansas City the next day and you think it might be a roadie job.

It must have just been the most surreal thing to fly out there thinking that you're going to be on the crew or something, and you end up playing that night to 30,000 people.

Winston: 80,000! [laughs]

Jon: In my fantasy memory of this you're wearing shorts and a Bart Simpson shirt. Is that correct?

Winston: No, people were growing their hair out and wearing flannel and stuff. I had a Henley shirt on and some long drawers and some kind of cargo shorts or whatever. It was the thing.

I had been aware of Bob Dylan. Like I told Ray, I sang the hits in my mind and made fun of him just like anybody else. I'd never really appreciated him until I'd had this girlfriend that was really into him. Desire was the record that got me into him, with Howie [Epstein, on drums]. He just seemed so shambolic. You could color outside the lines and no one cared.

The day before had been the worst thunderstorm in Midwest history. It flattened a bunch of towns, and I was flying through the end of it. The plane is going up and down, and there were five people on it. I finally get to Kansas City; there's no one there. I'm still thinking I'm going to move gear. I didn’t bring any clothes! I thought I was going to hang out with Charlie for a couple of weeks until the tour was over, so he wouldn’t lose his mind or whatever. Between the moment I landed and the first phone call, [he said], “No, you're going to go play with the guy.” I said, "What the fuck are you going to do?" He says, “I’m gonna leave and go play with Izzy Stradlin.” That was news to me.

So I got to the hotel. I had a really nice, deep bath. I sat there in that water until it went ice cold three or four times trying to figure out what I was going to do. Then I went down to the lobby. I saw Tommy Masters, the bus driver, and [tour manager] Victor Maymudes, who thought I was one of the Dylan nerds and chased me off. Tommy goes, "No, no, no. That's the kid that's coming out from Los Angeles, he's playing with him tonight."

We got to the venue, and then I went on the wrong bus. It was the crew. I nearly got eaten alive by all this big dudes. Jon Paul, the lighting director said, "No, that's the guy from LA.” He won $20 on a bet to see if I would make it through the first night. That night turned into almost five years.

We had dinner together in Louisiana at the last night of the first tour and that was really fun. We got to be human beings. I didn't just stare at the back of his head every night.

Speaking of staring, Bob didn't know what Charlie's friend looked like. I was like a cross between Huey Newton and Angela Davis. As I said in the book, he just would turn around like an owl and look. When he would play guitar, he would just come up to the riser. Those eyes, you've seen him thousand times from the album covers. I was just like, wow. Is it going to be like this the whole time?

It got to be really exciting and interesting and fun. People who played with him told me it’s no fun or whatever. I said, if you're a good sport, hell yeah it's fun. I could think of worse things to get paid to do and worse people to hang out with.

What's great about this book, if you look about who got asked to do all this stuff, there isn't a lot of similarities. It’s a really great portrait, cornucopia, a mélange. It’s American for sure, but it's unique and there’s this otherworldliness to it. The thing you had to be the most was yourself that day and give it until your hands bled. Mine actually did at one point.

Jon: There's a great quote in your interview. You're talking to [bassist and bandleader] Tony Garnier very early on, and he says, "Watch me and watch him, and it'll reveal itself." I wanted to talk to all of you about how crucial your eyes are when playing with Bob Dylan. The body language must just be the key to everything. Jim, let's go to you about that.

Jim: With Bob, it's not like he's up there grooving with his body. He's not that kind of singer, or at least he wasn't when I was playing with him. You would learn to read other little things, like what Stan said earlier about when Bob came over to him and said, "I like what you're doing." He was playing busy at the time, probably having a lot of fun. Bob sensed that, I'm sure. I got the impression later that Bob liked hearing the drummer having fun.

I think that artists like Bob Dylan, and others of his genius level, I think they can sense fear in a way that maybe we don't as musicians. Although I've gotten like that, in a way. When I'm on sessions, I can tell when somebody's afraid. Your instinct is to try to calm them down, help them not to be afraid. Those who are fearless are the ones that are fun to play with, because then you have to rise. That was the thing with Bob. I always wanted to rise to a level in my playing where I'm really contributing to the music and having fun and everybody could sense that, but yet I didn't want it to be about me. You got to be careful about that… That's usually the guitar players. [laughs]

Bob's body language was very subtle. Don't forget, I was playing with him live during the Slow Train era. There were times when he would look— and I don't want to be controversial or say things that make people uncomfortable, but if I'm going to tell you the truth here on this little Zoom session here, I'm going to tell you that there were times when I would be behind him playing, and his hair had that beautiful halo. The light would be hitting him just right. I'd be almost feeling I'm playing behind Jesus.

Now that's crazy. You say, "Oh Jim, come on." I'm just telling you the truth. That's the way it felt to me sometimes.

After that period was over, or toward the end, he had a picture sent to me by the office that’s just incredible. It's in my music room. The light is just right, and his shirt was hanging in a certain way. Like I said, that hair of his, it's from the back, and I'm hunched over. My left shoulder is up like this; I'm really digging in. I treasure that.

Jon: Stan, you have a quote that is something like, "Who’s ever at the mic, if they're not happy, your life is shit." I wanted to talk a little bit about those moments where maybe he wasn't in a good mood. How do you handle that?

Stan: My situation was probably a little unique because I did have a gang. I got to give full proper respect to those guys. I was one finger on a fist. When Bob joined, in my egotistical trippy brain, I was, "He's joined our band." That was the power of being in a group. Nobody's allowed to have a bad night in a band. You can't do that. There's no such thing. You can't have a flat tire on the car. You're out of there. You do that for more than a song, and you'll probably be politely told, “We can do this without you if you're bringing the wrong ‘tude.”

There were probably some soundchecks that were a little strange. We'd play one chord for an hour and 20 minutes in a semi-reggae groove. I wasn't sure if that was “Lay Lady Lay” or a Ramones song. I think one night we did “I Will Survive” by Gloria Gaynor. Fine! I'm willing to commit. It was really jocular. And he had the Queens of Rhythm. There was a lot of boogaloo going on up there.

Bob, if he wasn't digging it or was waiting to get the feeling, all he had to do was just put his head down and mow. Yeah, he ain't Tom Jones or Elvis but there's an arm when he's sawing wood, man. He was very physical at that time. Remember this is a long time ago, we were all young men, and there was a very physical element to playing rock and roll. It's a working-class job when you're in your 20s and 30s, even into your early 40s. It's not ‘til later you need to go, "Oh, I better try to figure out a new way in here."

We were physical and we were loud. Everybody showed their love in a gracious and aggressive way, and I loved it. I just loved it. It was right at the right time. I was still feeling machismo, and Bob was right there. You could push him. And if he didn't want you in— you know, drummers try to, "Hey, this is where we all come in." I remember there's a place in the movie [Hard to Handle] where he's playing harmonica beautifully. I think it's “Heaven's Door.” I decided in my infinite wisdom, this is where we're going to kick in.

He literally doesn't even turn around. Doesn't even bother. He puts his hand to the drummer. That was like, "Not now, Kato." I was like, "Uh-oh, I just put a fill into nothing and went off the cliff." Fine. Everybody in the band is like, "Ah, you fouled out.” You put your hand up and claim it. Like I said, having a group, that was a nice foil. I really believe he enjoyed it. He would come off the stage wet and sweaty. You'd even get some physicality out of him. You'd get a grab on the shoulders. It was sweet.

Jon: While we're talking about groups, Jim, I wanted to talk to you about what it was like playing with Bob in the context of the Wilburys. It seemed like he would have loved not being in charge.

Jim: I think he did like that, not being in charge, not being the major guy. They all loved that. George Harrison worshiped Bob Dylan, literally. This is no exaggeration when I say that George knew lyrics to some of Bob's songs that Bob had forgotten. That was fun to see Bob find that out.

I told this one story so many times, I don't know if I should say it again—

Stan: Please do!

Winston: Yeah!

Jim: I was beginning to clean up my act around that time. I was trying to stop smoking. I was tired of having pneumonia. Yet Bob, George [Harrison], Tom, and Jeff [Lynne] were all just real smokers. Just smoking all the time. When they're all sitting together on the bus and I'm the only one not smoking, I couldn't take it.

I got off the bus and I saw the other bus up the way, so I went there. I looked in and Roy [Orbison] was sitting there by himself in the driver's seat. I knocked on the door and he let me in. He says, "Hey, Jim. This is fun, isn't it?" I said, "You know, those guys only got together because of you. They just love hearing you sing, man."

He said, "Well, yeah, I'm the only real singer in the band. The other boys, they're all stylists." I laughed so hard because of the way he said it, just so matter of fact. I started thinking, it's true. Bob, George, Jeff, Tom, all of them, they're all great singers but they're basically stylists compared to Roy as a real singer. I went back and I told them that. They loved that so much. They thought that was so funny.

Basically the truth of the whole matter is that they were there because of Roy Orbison. They were in his band. When he split, it was horrendous. It was truly like your big brother gone, and quickly. Terrible. That changed the whole dynamic. They tried to not let it change too much. We did the other record after that. We did the one where we did it all live in the same room, just the opposite of the way the first one was done. It was great to be with those guys.

Winnie and Stan, we're three drummers that played with Dylan. I keep thinking of all the other guys, man, all the other cats that played with Bob who are really good friends of mine. Like I said to Ray, the author, Winnie and Stan's interviews in this great little book, Pledging My Time, they're my favorite interviews. Now, having said that, I haven't read many of the others yet. [everyone laughs]

Stan Lynch should be a writer because he's got that kind of mind. He'll make you laugh, and yet he'll get deep with the stuff. Winston, you wouldn't think a young kid like him— I realized when I first met him, he's a deep son of a gun. That’s why he played so good. He wasn't just a kid coming on the scene and everything. I feel like we're talking for all the cats. There's only three of us here, so we have to represent all our fellow drummers that did time with Bob.

Fan questions

Henry: I have a simple question for Mr. Watson. To what extent did you guys, Bob, the band, refer to your tour as the “Never Ending Tour”? Or is that just a fan thing?

Winston: I don't know. According to historians, that started in '88 and then maybe ended before me. I'm not really sure, but it's cool to be included in that, if that's the case. We did go a lot of places; you could look at it that way. If you were someone that likes sleeping in their own bed, that's not necessarily the job for you. You leave with one set of clothes and you come back with a different one. Your kid's driving; you were changing their diapers [when you left]. But I have no idea. The names changed for a lot of the legs of the tour like “Why Do You Look At Me So Strangely” kinds of things. You'd have to ask the people who were working with him before I came up in the scene.

Adam: Do you ever have the actor's nightmare about being on stage with Bob and no idea what to do? I don't even play, and I've had that nightmare.

Winston: Yeah, there are a couple of minutes where it's sort of knife’s edge like that. But in my mind anyway, I don't think failure in the field is acceptable, or it never has been to me. Like I said, I was invited to do this thing that I had no idea would have all these implications, and the actual history involved. To me, it was just playing music with a bunch of cats I didn't know. Then it just keeps going and going.

Jim's right, I think Bob can sense when the deer's in the headlights there. So you have to act accordingly. Because you are all adults. It's not like with your group of guys who you've been teasing since you were a kid. These are grown men who you don't call nicknames unless you know them. Your job was to get out there and do however many hours or how many songs or gears or chords. What you have in that day is really important. The more I stopped thinking about the history, it just enabled me to be not so struck by all of it and just be human and play the drums like I was in my mom's den when I was a kid.

There are times when his voice would crack when he started really, really singing in the middle and later years when I was with him. Like Jimmy said, you’d have to go someplace quiet afterwards. I'm not necessarily a religious guy, but there was a thing there, there was a definite intangible there that ran into my heart. I can't explain it, because I don't know the man like I know my best friend. And he is just a man, like all of us, but he makes you pay attention in a way that you don't expect.

I did show off a lot, but I think if it was that bad, I would've gone home the second night or whatever. I know he wanted me to be who I was, and at the time I was like that, but I didn't have to be like that. I had watched The Last Waltz on VHS in the bus, and I wept uncontrolled after watching Levon sing and play. It was after that where I got rid of all the garbage and just went down to a four-piece kit, just to make space and hear him sing those words.

Noel: I feel like I'm on a call with the Avengers of drumming. Stan, you mentioned that there was a certain physicality to Bob that I was a little surprised by, he got into the moment and he might give you the slap on the shoulder or whatever. I've always understood him to be a reluctant physical engager like, don't hug me, don't get in my space. Can you talk a little bit more about that? Do you feel is he the type where when you get off stage, he might high-five you, or you could give him a hug if it were a good show? Or did you feel like there was some reluctance to the physicality part?

Stan: I was so naive. I have to open almost every conversation about Bob with that. I really thought he was a guy in our band, and I treated him that way. Like, "Hey, Bob, how ya doing? Nice shirt." My relationship with him started literally on one of the first rehearsals, and it's in the book, where I had to leave rehearsals early to go see Sammy Davis and Frank [Sinatra]. He said, "Oh, I love Sammy and Frank." I said, "Well, I got an extra ticket." So before I really even knew him, only played an hour with him, he's in my car and we're driving to the Greek to go see a gig.

I'm kind of going, well, he's just a dude. He's a cool dude; he's got a Harley. Like I said, I'm so naïve. Refer back to statement A. My relationship with him for the first year and a half was based purely on, let's talk about girls, let's talk about motorcycles. Literally I was that tawdry. As Benmont is explaining to Bob, “There's two versions of your song, one's in D and one's in C,” I'm going like, "Hey, whatever!"

It was one night in Italy that it hit me. I had that moment that you guys have both described so perfectly where I was on a stage, he was in my monitor, well placed so I could hear him. Then there was a part of the show when we were ejected, and Bob did four or five songs himself. I just sat there in the dark watching Bob with the halo and the beautiful hair. As he's singing “Blowin’ in the Wind,” I realized, "This son of a bitch actually wrote this stuff."

That was a year and a half into working with him that the Bubba in me caught a glimpse of what was really happening here. I wept through all four of those songs, and I never recovered. At the end of the show, I remember racing up to him and saying, "You were amazing tonight. You really were amazing. You touched me. You hurt me. I felt every word." He looked at me with a straight face, pulled down the shades, he goes, "Stan, are you all right?"

And I wasn't. I was so touched. That was where the fever broke finally. It was that moment where I went, "Right, one of these things is not like the other. This is a very unique, beautiful human being."

Will: I have a question for Winston. One of my favorite bootlegs that I listen to all the time is what's been deemed the Jerry Garcia tribute show. That was about just a few weeks after he died, I think a radio station gave out a couple hundred tickets to. It was like a lot of covers, but he played “Willin’” and “Confidential” and some Dead covers obviously. Do you remember that at all?

Winston: That was pretty raucous. It was a bar, I think the logistics of it were sort of not ideal, but I remember everything being just so feverish. I do remember it being a rock show. If you have that recording, then you can hear it. There was something on his mind that night, and some of it translated into some pretty savage stuff.

He definitely embraced something while I was with him, and I got to watch some of that happen. I think [the band was] very visible then, maybe to a shameful degree, but to get included in that period— well, it didn't really matter to me at the time I was doing it, but coming across books like this and hearing it from a listener's perspective of someone who enjoys him and our music, I'm always interested. Like as I said, I was pretty fortunate to be involved in all of it. It’s a little more difficult to remember the actual show itself unless you're listening to it; then you're going to go, why did I [play that] or what was I wearing or whatever. That minefield has already been crossed. When you're trying to cross the snow and there are no footprints and you can get blown up any second, you're just trying to be true to yourself and not take the man's money for nothing.

As it evolved, there was a sound that we worked on. Man that was hammered out like an old Turkish cymbal. We rehearsed for hours and hours and hours. Jimmy said like, "We be on A for like two and a half hours," and then you figure out, "Oh gosh, it’s ‘Idiot Wind’ or something like that." He’ll just start singing over something that he can get in the middle of. You do that extra tag on that on the five or whatever, then you come back to the top of it. He was famous for doing stuff like that. There is definite body language, but it is so subtle and so unique, you really have to pay attention. Somehow, you couldn't be afraid. You could be terrified, but you can make some pretty cool racket if you're terrified in the right circumstances.

My favorite part of, the whole thing was when he would do “Little Moses” or “Boots of Spanish Leather” or “Hattie Carroll.” Oh my God, he reduced me to a bubble one time. I was listening to “Hattie Carroll” one night. I could hear only him, guitar, and the air conditioning in that hall. I was moved so much that I could not climb on my kit afterwards and make that racket. It was so hard. But it was part of the set where we would want to come back with “God Knows” or something really rocking.

I even said to him, “It could be just like you out there.” Because I had watched Dont Look Back and stuff. When I watched that early stuff, I would look at him during our daily things, I would see those same eyes. You didn't have to be religious or any of that to feel it.

He said to me once that he liked how consistent we started becoming. It wasn't a gang like Stan came with, but we became a little gang. Something you'd see in a Patrick Swayze movie like Road House. Like yeah, we could kick your ass with some 12-bar.

Ray: Before we wrap, I wanted to ask all of you, what are you up to these days? Is there anything we should know about, something you're working on?

Jim: I've been working with these young girls. This one girl the other day was so good, it was blowing my mind. I asked the producer, "How old is she?" He said, "23." I'm thinking, how do you get those kind of skills and still have the soul of an old person? I really love that. I love seeing that the new generation of artists are really killer. A lot of them. People are smarter now. I think maybe every generation has said that, but now because of the internet and everything. My wife comes in the room, she says, "Watch this." And she shows me some little three-year-old doing the most incredible stuff, whether it be music or dancing or talking, anything. Or you see a little kid interviewed on the street, a little baby kid, and they're smart. They already know stuff. That's the way the world is right now. I find that fascinating.

Stan: I live in a very remote area in Florida, and I have my own little studio. I work remotely because that seems the way the world has gone; I've learned to fileshare. I play pretty much every day, either the drums or the piano or the guitar. I love making music. Fortunately, I get to make music with most of my friends. Just the other night I got to make a little noise with Benmont.

Jim: I heard about that.

Stan: That was splendid. That was a soul-scratcher all the way. We both got up after playing a minute or two. I couldn't take my hands off him. I couldn't not touch him.

Music to me has just gotten richer, thicker. The stew has just gotten so distillate. When I go to play, I can finally listen. I hated Pro Tools for the first seven years, but now I've made friends with the clock. He's my buddy. He's more of a suggestion. I can dance with him now, and I'm not intimidated.

As Jim would always tell me when I was a little kid—I met him when I was 19 years old, making the first [Petty] record—"Stan, it's about the groove. Put one hand behind your back, man. If you don't know what to do…you'll know. Find it." My first meeting Jim as a little boy, he doesn't remember it but boy, I'll never forget it.

Jim: I do remember!

Stan: He said, "Shuffles are going to be tough. Put one hand behind your back.” About an hour later, I was playing “Breakdown,” thanks to Jim.

Like, just the fact that I've been here this long, I get to do this, I get to see you guys again, I'm very grateful and I feel really fortunate. Music, what a church it's been, man. What a church.

Winston: I live in West Hollywood, then I have a little place here in Tucson, Dust & Stone Studios, where my band XIXA do this cumbia infused rock stuff that we've been taking around the world for the last 10 years or so. They're all young, handsome men in their 30s, so it's a pretty physical gig.

I've been playing the last two years now with Wayne Kramer, and there's a MC5 record in the works. I was six months old when Bob's first records came out; I think I was eight or nine when first MC5 record came out. I remember looking at the cover of that record, at Wayne and Rob [Tyner] and everyone, going, "Wow! Those guys are so savage.” Then 50 years later, I'm at this place in Detroit with Wayne, and we've become really good friends. It's loud and it's fun and it's physical, and it gets me in shape. I'm going progressively deaf, but having a really great time.

I'm still making music pretty much on a daily basis. I’ve fallen in love with stringed instruments, guitars and bass especially. There's a drummer joke in there somewhere, but I'm not going to say it.

If you want to hear more Bob Dylan stories from Jim Keltner, Stan Lynch, and Winston Watson — not to mention 40+ other musicians who’ve played with Dylan — click the button below:

I loved this Zoom event, Ray, and am glad that it can now reach a wider audience. As someone who also writes about Dylan, I especially appreciate the extra effort you took to provide a transcript. There are so many good Dylan podcasts out there, but if you want to quote them in a written work you first have to go through the tedious play-pause-type-rewind-play-pause-correct-continue process of making your own transcription of the parts you want to quote. I'm willing to do that, gladly, since some of the leading voices in Dylan these days are putting their views out there in that format. But it sure is a welcome gift when the work is done for you by the podcaster--thanks, Ray!

Thanks ray - I enjoyed the zoom interview with these special musicians thoroughly. You’re the best!