Billy Cross Talks Playing 100 Shows with (and Getting His Hair Pulled By) Bob Dylan

1978-06-26, Westfalenhalle, Dortmund, West Germany

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan shows of yesteryear. Subscribe here:

Update June 2023: This interview is included along with 40+ others in my new book ‘Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members.’ Buy it in hardcover, paperback, or ebook now!

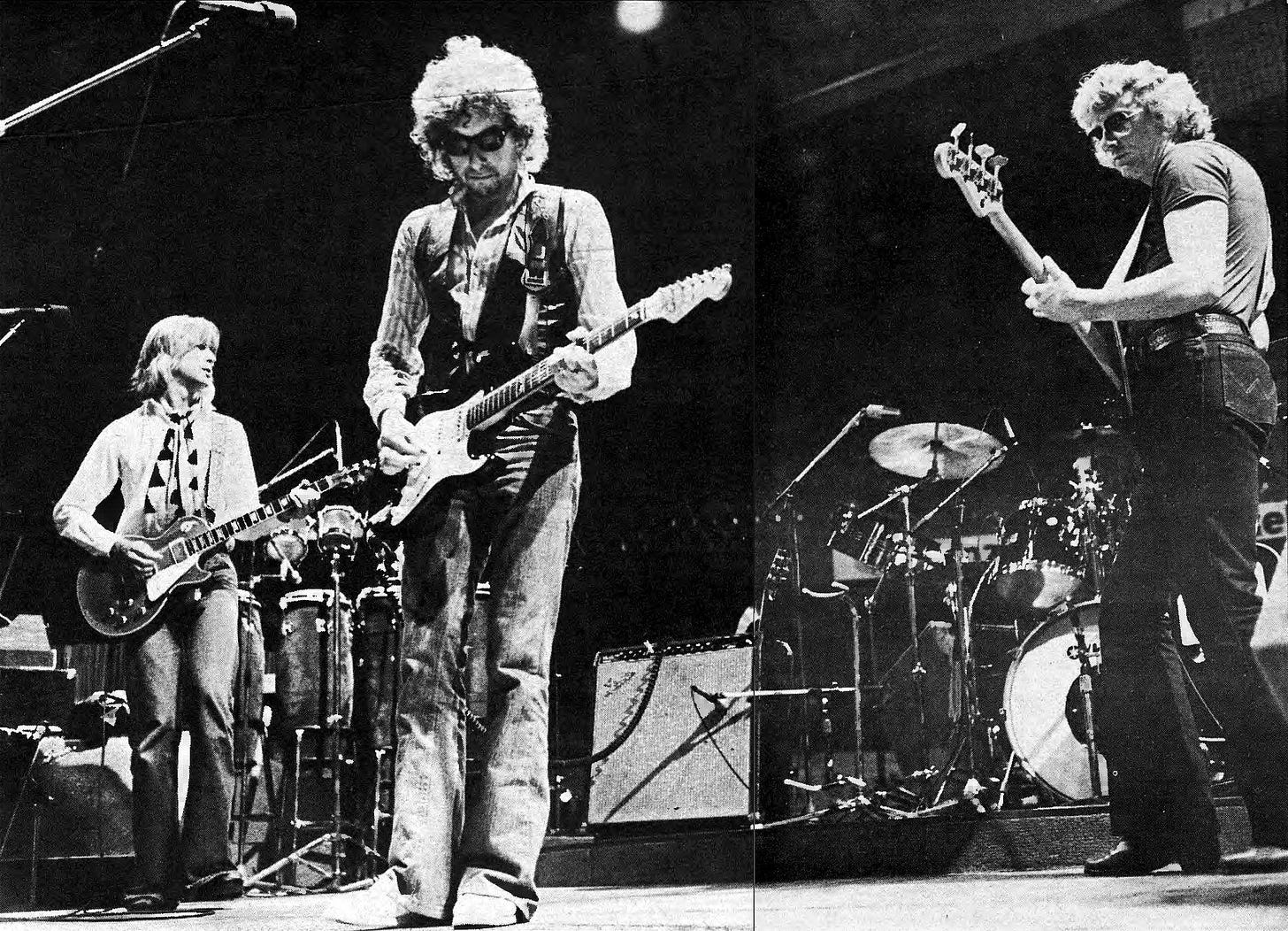

1978 was, to that point, the busiest touring year of Bob Dylan’s career. By far. At Budokan remains the tour’s best-known document, but the live album was recorded at some of the very first shows. The tour continued all year, a total of 115 concerts in 10 different countries with one of the biggest bands of Bob’s career. I talked to one band member, pianist Alan Pasqua, a few months back, and today we hear from lead guitarist Billy Cross.

Billy had a busy career before Dylan called, playing with Sha Na Na and Jobriath as well as a variety of Broadway musicals, including Hair (I wonder if his long golden locks helped him land that gig) before moving to Denmark in the ‘70s. He’d also played with Link Wray and Robert Gordon alongside Dylan’s Rolling Thunder bassist Rob Stoner, which would lead him to Bob. But I’ll let Billy tell that tale…

Let’s start at the beginning. How did you get involved in the tour and in Bob Dylan's musical world?

I went to Columbia University with Robbie Stoner and we played music together. We had this band called Topaz which was an embarrassment, but nonetheless it existed. When I was back in Copenhagen, Robbie had been playing with Bob on the Rolling Thunder tour, and he had played on the Desire record. Then, when Topaz broke up, Bob had contacted Rob again and said, "Come out to LA, I'm putting a new band together, I'm going to do another tour." They had auditioned about 34 guitar players as far as I know, and Bob simply wasn't satisfied. I don't know why.

Finally, Robbie said, "Well, I got this friend who lives in Copenhagen. It's far away but he's a good player." They called me up, Bob and Rob, and they said, "I'm going to give you an airplane ticket and you're going to come over and you're going to audition.” and I did.

Arthur Rosato was the main person in the road crew, in charge of putting everything together. I came into the rehearsal place down in Santa Monica and he took me aside and he said, "Look, all the guitar players who have auditioned have been intimidated. What you've got to do is you've got to play loud." I just turned up and played loud.

After the audition Bob walked over to me and said, "What are you doing the next year?" I said, "Well, I hope I'm going to be playing with you." He said, "Yes," and that was that.

Were you surprised at the size and scale of the band? At the time, he wasn't thought of as having these giant bands with backing singers and stuff.

When you're presented with a reality like that, you just accept it for what it is, like kids who accept their parents even if they're weird.

Was it a challenge to make your mark in that environment musically when there's so much else happening?

Well, I wasn't really interested in making my mark. I was interested in doing whatever I could to make the music sound right. I didn't feel that I needed to manifest myself stylistically or personally. I was just so happy to be there.

What's the next thing that happens?

We rehearsed like crazy, just day after day after day after day, in an old gun factory on Ocean Avenue. We would eat really good lunches, great soups. and hung out in this place in Santa Monica.

What would a typical day of rehearsal look like?

We all show up I guess in the first part of the day, and then we get tuned, make some noise, smoke some cigarettes. Then Bob would show up and we just start playing. And then we'd quit!

We still had to audition some people. We had to get a drummer. The keyboards, and drummers, and some of the girls had not been sorted out yet. We went through a bunch of different drummers to play with.

One thing I'm always curious about, and especially with this tour, are where the arrangements come from. You got a reggae “Don't Think Twice,” that cool “Maggie’s Farm.” Is Bob or someone dictating the arrangements, or you were just jamming until something comes out?

They basically all came from Bob. Bob had a distinct idea of every single song on what he wanted to do. Each song had a direction, each song had a genre identity, each song had a presentation that was his.

[I came up with] some small details, like the intro of “Mr. Tambourine Man.” He said to me, "Come up with a guitar intro." I thought, "Oh, Jesus Christ. What am I going to do?" I came up with that. That's about the only thing that I remember that I did specifically that was recognizably significant.

Let's go to Japan. That's probably the most famous part of the tour, because they made a live album out of it. What do you remember from that run?

Musically, we were pretty green. I think we all would've preferred to have recorded shows later in the tour. We were professionals, but bands tend to get better as they play, and we definitely got better.

The shows at the Budokan were interesting because they had guards who stood in the aisles and prevented people from standing up in their seats or getting overly excited. It was a strange feeling. I played in the Soviet Union and there was a similar feeling there. The authorities didn't want the people to emotionally react too strongly, and have that emotion carried into physical behavior. There was a feeling of repression, but it wasn't bad. In America, people will drink as much as they can, and smoke as much as they can, let it all hang out. That was very much not what was happening in Japan.

Is that difficult as a musician, you want a back and forth with the audience, and not really getting it?

Audience communication with the band, it's fun to a certain degree, [but] when I'm on stage playing, I'm really thinking about the music. What's happening, how can I make it sound better, am I doing a good job, is the groove right, is Bob happy, not throwing me any weird looks or anything? Maybe I'll be thinking about a couple of girls in the first row. [Mostly], I'll be thinking about the music.

Are you getting feedback from Bob? “This song needs work,” etc.

For a person who is as [musically] articulate as he has proven to be over his career, which is on a level with Shakespeare, his communication verbally with people wasn't of the same character as his abilities as a songwriter. He's a very instinctively reactive person. There wasn't a lot of talk about stuff. We kind of did it, and if he felt something wasn't going the right way, we would do something else. He wasn't verbally expressive in terms of negotiating the music.

It's not a thing where you would get notes after - "hey, the guitar solo sounded wrong" or something?

“On bar 54 of Just Like a Woman, you played an E flat, that's an E natural” - no. It's not like rehearsing for a Broadway show. He was very friendly and very warm. He was lovely, absolutely lovely, considering what he's been subjected through his life at that point. Everywhere he goes, somebody thinks he's got the answer that's blowin' in the wind. I thought it was unbelievable that he could be as normal and personal and pleasant as he was.

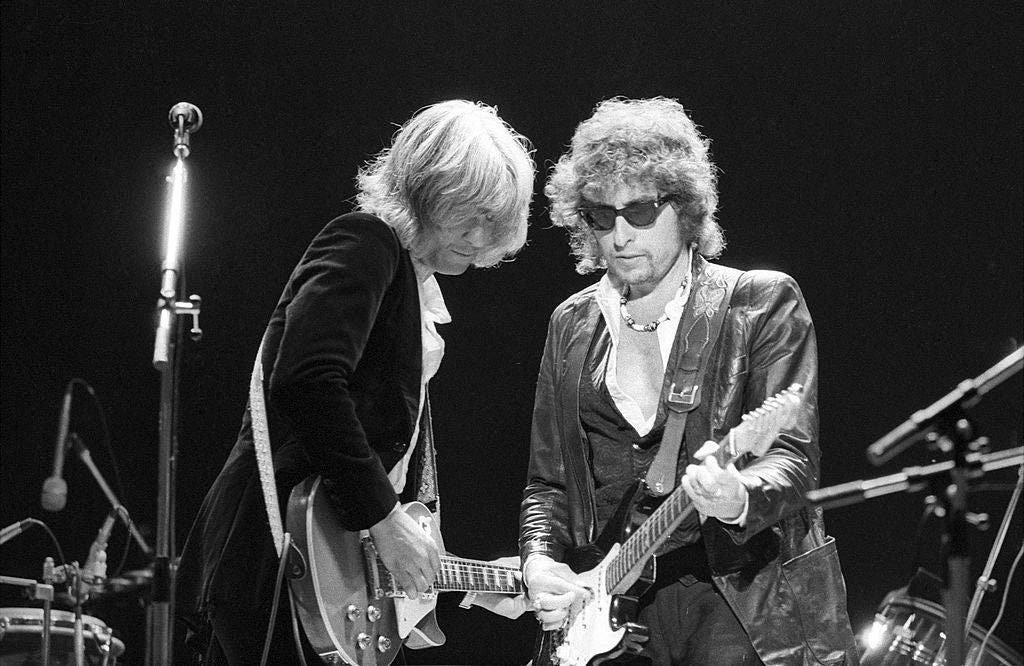

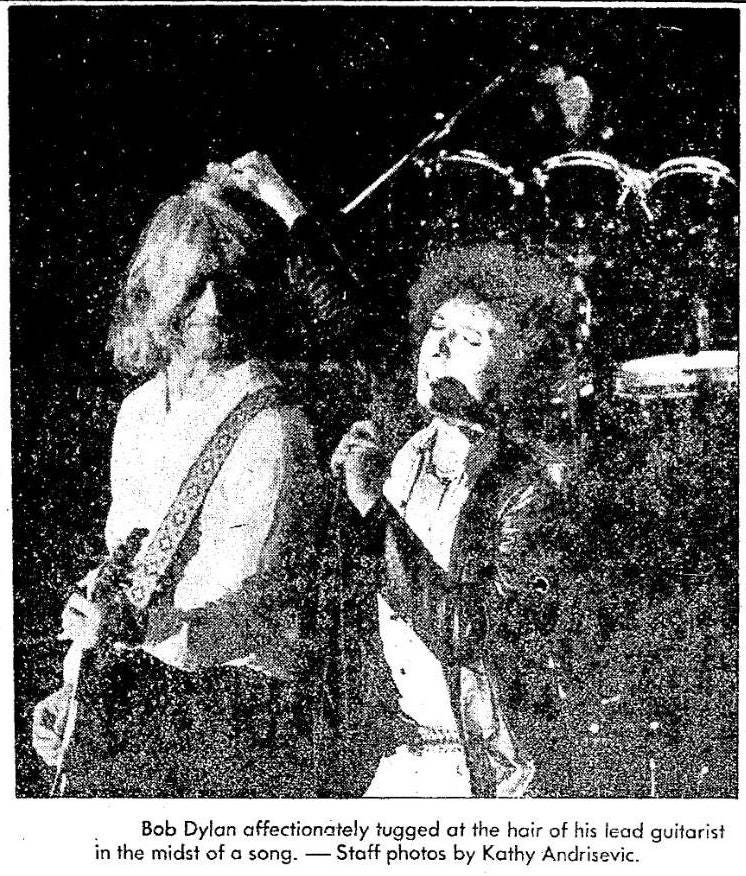

I was looking up some photos of you two and I found a few where he seems to be pulling your hair on stage. He’s not someone who’s known for goofing around like that. Was that typical?

No, I don't think he's done it before or after. I must've inspired some sort of ironic distance. Over the years, people have sent me photos of me and Dylan dueling guitars on stage, or him messing up my hair, or pulling up my leather pants, which he did one night. As I said, I found him in relationship to me to be very warm, very loving, very friendly, very understanding, very generous.

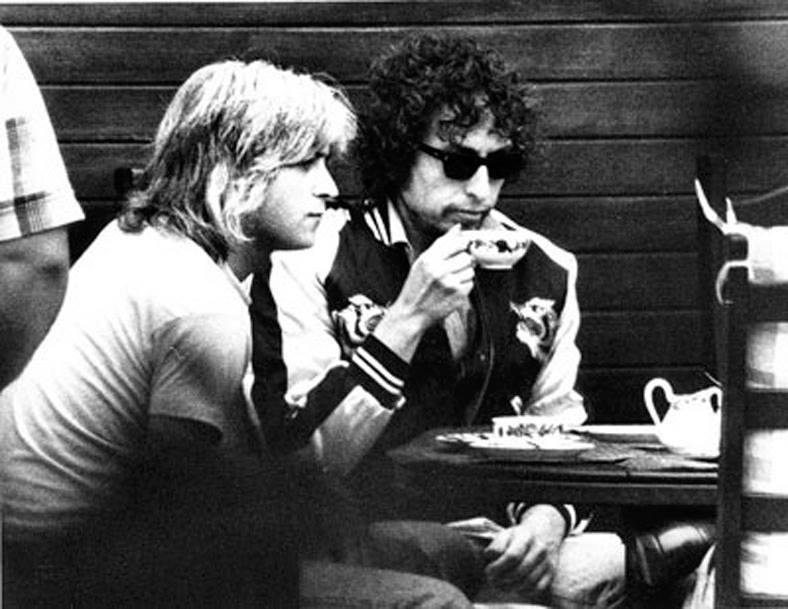

I can tell you one specific example, even before he knew me well. I had been away from my wife for quite a while. She's Danish and she had gone back to Copenhagen to start up the beginning of her master's degree. I've been on the road with Topaz with Rob and I hadn't seen her in quite a while. When I got the [Dylan] gig, I flew her out to be with me in LA while we were rehearsing. I asked management if I could be allowed to bring her on the road on this tour, because it really was amounting to an awful long time away. We had been together for four years at that point and those things are tricky with relationships. I was frightened that all the experiences I would have as opposed to the experiences she didn't have would bring us further away from one another than was healthy. Management said, "No way, you can't do that."

I had to think, "Do I want to sacrifice my marriage for this gig?" I was very much in doubt. I was tormented by it. I went to Bob and I said, "Bob I really have a situation here I need to ask you. Lise and I have not been together in about five months and this would mean another three months that we would be separated. Do you think I could bring her?" He looked at me and he said, "Of course you can bring her. I'll make sure that when you pay for a ticket, we take it out of your bulk salary not after your salary after taxes. We'll get her on the insurance program for the tour. Everything will be set up. Don't worry."

In my book, that's big stuff. It was an understanding and a warmth and a generosity of spirit that I don't think I've encountered from other people in the business,

Another thing was we both had back difficulties. He had the injuries that he got from the motorcycle accident. I had a gymnastics accident when I was 17 that gave me a disc that would come out every now and then. We used to go swimming together when we were on the road. [Tour manager] Gary would find somebody who had a swimming pool or some public pool and we would be driven over there so we could swim laps to train our backs up. So we spent a good deal more time together than he would have spent with a lot of the other people because of that.

In terms of the concerts themselves, did you have any particular favorite songs to play live?

I think my favorite song is one I didn't play on [laughs]. It was the way they did “Tangled Up in Blue,” I thought that was unbelievable. I had goosebumps every time he did it. It was just Bob and Steve [Douglas] and Alan [Pasqua] and it was remarkable. He always sounds best when there's the least amount of music behind him. He's such an unbelievably great singer that I don't need a lot to listen to Bob. Hearing him by himself sometimes is even more powerful than hearing him with a band.

I'm a big ‘78 fan, but one of the criticisms you see is what you're saying: That there's so many people on stage, that Bob is getting overwhelmed. Did you ever feel, in terms of what you're saying about him being great when it's stripped-down, that sometimes there was almost too much?

Well, I wouldn't say that it was too much, because it managed to function. When you've got that many people on stage, that's not easy on any level. It's not easy in terms of the sound mixing and it's not easy in terms of arranging the instruments. Everybody wants to be a part. Everybody would have a natural inclination to play. I'm a record producer, and the trick is almost always, how can you create the fabric with a few colors as possible and still get the impact?

Every now and then, if I had my druthers, I might have thought that there could have been fewer people involved. The first time I saw Bob play was in 1965 and that was when he did the first show acoustic and then he had the [backing band]. It was just enough to cover it, and it was a remarkable concert.

There wasn't one person on [our] stage who wasn't a killer on his instrument. Sometimes I would just lay out and listen to what was going on and then come in occasionally with a musical comment. Bob could have taken just about anybody out of that band except for the bass player and drummer and everything would have been fine, if you know what I mean.

Bob is an exceptionally good guitar player. He's got an unbelievable power in his playing. His rhythm is so strong and his phrasings are so intelligent. His cultural awareness of the musical tradition in which he moves is so complete and so deep, that if you really listen to what he does, it's like going to school.

How does that affect what you're doing as the other guitar player on stage?

It made me shut up a lot. I was much younger then, so I was more of an asshole. I probably played too much.

This is a tour that was relatively consistent night to night. Would a song change much between one show and another, in terms of what Bob was doing on guitar, vocally, or was it laid out the same night to night?

When you got that many people in the band, you can't start taking a left turn where you usually do the right one. They were pretty well worked out. Tempos could change somewhat, but the intensity and the basic feel was more or less the same. Later on, during the American tour things started to happen, where he would just start a song without saying which song it was.

How else did the tour change over the course of the year? This was his longest tour ever.

First of all, we lost Robbie Stoner after the first tour, and he was replaced by Jerry Scheff. That made a difference in the dynamic of the situation.

How so?

Robbie takes up a lot of space personally and musically, and Jerry was more laid back. Whereas Robbie's bass playing maybe was more in your face, Jerry's was more in the supportive area. They're both great players, it wasn't that one was better than the other, but Robbie's playing is much more upfront, he steps up there. If you look at the Rolling Thunder tour you can really hear that, him and Howie. Howie was the drummer at Topaz. They were an unbelievable unit, Howie and Robbie. They were a killer.

Ian wasn't that crazy about playing with Robbie, but he really loved playing with Jerry, so that changed it a bit. Robbie's fire was gone from the band after that, so it was replaced with a more relaxed feel. Robbie was closer to the Sex Pistols and then Jerry was closer to Elvis.

When you start touring into the degree that we toured, there's a certain mental fatigue that occurs. People change a little bit on the road, things happen, they miss their families, they get tired of hotel rooms. But there were never any conflicts, there was never any time when things were unpleasant. By the time we ended it all, everybody loved each other even more than when we started.

The European shows were amazing. I think that was the best for me. They were the shows where we played the most musically and the strongest. The American shows, as always in America, gain an intensity because Americans are more intense. The reaction from the people engendered in us a slightly more aggressive attitude. The Japanese shows were the most proper, the European shows were the most musically satisfying, the American shows were the most intense.

In between tours, you recorded Street Legal. What do you remember about those sessions?

We set up in our rehearsal room and that was cozy. Don DeVito was a feel-good producer. He makes everybody happy and makes sure that things go as they should and the people make the music they make. He's not like a T-Bone Burnett, who goes in and does stuff, or a Roy Thomas Baker, who records everything 14 times, or a Phil Spector, who knows exactly how he wants things. Don was the right producer for Bob in some ways. The sessions were fun and they were very quick and they were very instinctive, the way Bob was.

I wasn't crazy about the sounds that the engineers got. It was Wally Heider's people who did the setup. It could have sounded better. I remember at one point, I was on his case, saying, "Bob, it could sound better man." He said, "Billy, my records are my music played by me and the people with whom I'm playing in that room on that day. That's what my music is." I thought that was a pretty cool way to look at it.

I think the sessions were good. They were fun; they were not uptight or unrelaxed. [But] Bob is without a doubt an intense human being. It's not like you're recording with-- who’s that guy who does “Tequilaland” or whatever?

“Margaritaville”?

Yes, “Margaritaville.” Jimmy Buffett. It's not that. This is a man with an intensity into his articulation as a musician, as a writer, and as singer. This is not for kids. This is very, very elusively powerful stuff.

How were you learning the songs? One or two you had played live but most you hadn’t. Is he sitting you down? Is he just playing and you have to figure it out as he goes?

Essentially Bob would have a song and start playing it, and then the rhythm section would get a pattern together. People will try to figure out where to put their sounds and their colors in. It’s folk music.

Music today is much more like opera. You have a pattern, and you put things together around it and you can take them in and out technically in the studio. The technique of recording is different. It's much more akin to classical music with a huge arrangement like a Beethoven symphony might have. This stuff was much more so down to earth, worked out like folk music. "Does it sound good? Okay, that's all right then."

I was looking at some of the session logs and I saw there's a bunch of outtakes that I don't think have ever been released. More than I was expecting, song titles like “Walk Out in the Rain”--

Oh yes, I think he wrote that with Helena. I don't really remember the ones we didn't use. David Mansfield did an article in Rolling Stone and they sent it to me. There's this recording from our last gig in Florida, a song that showed up on the first religious record [“Do Right to Me Baby”]. This is the first playing of the song that ever existed, we did it with our band.

“Slow Train,” I have the original recording of that from the soundcheck before it was even finished being written. He didn't have all the words. I know “Slow Train” because I got it on a cassette, but this song we were played live, I had no recollection of it whatsoever. Totally, completely blank.

I want to ask you about one outtake from this era that I bet you do remember, “Legionnaire's Disease.” How did that end up with your Delta Cross Band? I've had that for years and I didn't make the connection that that was you until preparing for this.

We were getting ready to do our third album and we were running out of material, essentially, but I had all these great tapes from our soundchecks with Bob. Bob would play “Stones In My Passway” and all these old blues things that almost nobody ever heard of. And Delta Cross Band was essentially a blues band.

I'm going through the tapes and all of a sudden, I hear the song and I'm thinking, "Hey, that sounds pretty good." I wrote Bob and I said, "Hey, Bob, is it okay if I record this song?" His wonderful lawyer, Jeff Rosen, wrote back and he said, "Yes, Bob says, it's great and here are the proper lyrics." We recorded it and it was a big hit over here.

Bob's never released any version. You're the original version of that, at least, publicly speaking.

I think it's the only version. I don't know of anybody else ever having to record it.

It's a strange song. It's a very strange song. Musically, it's pretty close to “Like a Rolling Stone,” but it's a strange lyric because it's hard to tell what the attitude is. It's very narrative, it doesn't take an attitude, it just tells it. You can't tell what the narrator is thinking, which in itself is a strange thing for a song to have as a quality. That's what struck me.

I'll have to go back and look at the lyrics with that in mind. I really like that song, and the fact that he never released it even as an outtake, I think a lot of people don't know it. Or the ones who know yours maybe don't even realize it was by Bob.

Who else could it be? [laughs] Maybe Springsteen. But there are no cars in there, so it couldn't be Bruce.

You mentioned your blues background. One thing I enjoyed diving into these shows is you all played blues cover sometimes to open. You did “Love Her With a Feeling,” “Steady Rolling Man,” a bunch. Was that something that evolved out of these soundchecks you're talking about?

If I remember correctly, he would just start them. He wouldn't say anything; he just starts those songs. It'd be 22,000 people out there and we'd be all set up and you'll hear [him play] dun-dun-dun-dun-dun and you think, “Okay, here we go.” I love that. I absolutely adore that. We have a word in Danish, it's so perfect for it, it's befriende, and it means that it frees you up, it allows your air under your wings. When somebody in front of 22,000 people has the confidence and the will to just start a song and the trust in his band to do it.

You probably knew all those songs already, right?

No! Most of them I knew, but I'll tell you something, Bob would pull these things out, "Hey, have you ever heard of--" He'd give some name I've never heard of in my life and I’d go home to the hotel. There was no internet back then, so I'd call up some people I knew and say, "Hey man, have you ever heard of Blind Melon Chipman?” or whatever it was.

He was unbelievable. Look, if I knew half of what he's forgotten, I would be one of the most well-educated musicians on the planet. He is really a person who did his homework. His knowledge of American folk history, and that's what the blues is, is unreal. He and Keith Richards, those two people have a passion, a love for that music that is so deep and so totally devoid of commercialism. It's simply affection for the music and tremendous knowledge.

Earlier you mentioned “Slow Train” and “Do Right,” where Bob was first dipping his toe into the Christian gospel thing. Did you have any sense that that's what was happening? There's that story of a cross getting thrown on stage while you were with him and that led him down this path, etc etc. Was there any awareness among you or the band?

No, I saw nothing coming. I was very surprised, very surprised.

There was a thing in America being-- What was it called? Born again. Born again Christians. There were certain people in the organization, David Mansfield's girlfriend, for example, and then one of Bob's girlfriends, Alice, she was also into it. Steve Soles was into it and David was into it too for that matter, if I remember correctly. They were all coming out with this Christian shit, and that's not exactly my cup of tea, I'm not religious by any means. I live in Denmark, this is the most irreligious country on the face of the earth, thank god. When those kinds of things came up, and they came up almost never, I would just back off.

T-Bone got born again late in the '70s after Rolling Thunder, because of The Alpha Band. That was David and Steven and T-Bone. T-Bone was a very charismatic and powerful individual, and I believe he just took everybody along on that. I think he's still pretty religious. I read some stuff he wrote that was unbelievably intelligent, but his imagery was Christian imagery. He's managed to internalize it in a way that works, I think, even though I'm not a great fan of religion on any level. He seems to have the respect for other points of view and he also sees it as much culturally as he does in terms of actual religious dogma.

You said occasionally it came up backstage or something, what did that look like?

Steven. Steven Soles would say something about religious stuff. He was the only one that ever did really. David never did, Bob never did, Alice, of course, had nothing to do with the tour, and David's girlfriend didn't do it - but she was the one that took Bob to the church, which started the ball rolling. There's no way for me to even in any way speculate on where it came from, why it came when it did, or what was the cause.

There was no awareness among the band, for instance, when you're trying out “Slow Train,” "Oh, what are these lyrics about?"

There were no religious words in “Slow Train” when he wrote it at the start. I sat next to him when he wrote the song on the bus.

Oh, really?

Yeah. He had this notebook he carried around with him and he was writing that song on the bus and we were sitting next to each other. I remember that very distinctly. Obviously, he was writing in other places and other times. He never wasn't writing. But, no, the original “Slow Train Coming" the only words that were actually recognizable was the chorus. Everything was just sounds and words, you know, he would make up stuff.

I didn't have any inkling whatsoever. But at that point, we were at the end of three solid months on the road in America, and people were-- I wouldn't say we were dragging, but you could tell that we've been on the road for three months. That's a long time.

Do you have any other memories like the one of “Slow Train,” of him writing, of being around when he was writing something or working on something new?

He was always writing. It's just like some people breathe, some people drink beer, some people smoke cigarettes. He wrote. You know who Truman Capote is, I'm sure?

Sure.

He was delivering a lecture to some university and he was well into the final phase of his life, when he was irregular, to say the least, and drinking and taking pills and everything else. Somebody in the audience raised his hands. "Mr. Capote, how can I become a writer?" Truman was drunk and he got off on his high horse and said, "You can't. How could you ask that? You don't become a writer; you are a writer. You write because you have to write, you write because every day when you wake up, you have to write. It's the first thing you think about in the morning and the last thing you think about before you go to sleep at night. You don't become, you are."

I'm not certain that's what the kid meant. I think he meant how do you technically get there. It's a well-known anecdote and, in some ways, it reflects what I perceived as Bob's reality. He writes. That's what he does. He doesn't buy fancy clothing, he doesn't buy snazzy cars, he doesn't need to impress people, he just writes. That's it, he's a writer.

Sometimes, after concerts, we would get together and play. He always had a piano in his room. That was part of a thing that he had on the road. If humanly possible, there will be a piano in his hotel room.

What were those hotel room jams like? Can you set the scene?

Nothing big. Sometimes, you might end up in Bob's room because he was social and nice and fun to be around. There'd be a piano and sometimes he'd pull out some guitars and play, and sometimes he wouldn't. It was not a big thing. You got to remember that those shows were three and a half hours long. People were bushed.

I bet. I'm surprised it ever happened.

When you're working with somebody who's as dynamically inspirational as Bob was, it's not hard. You never feel tired and he never let us down, even when he was sick. He gave 130% every night, I've never seen anything like that. He never, not one night in the entire time I played with him did he ever not deliver over 100%.

What do you mean when he was sick?

I think it was a week or so, he had a real bad cold. He's spitting up phlegm all over the place on the stage.

I'm from Chicago and that's like a Michael Jordan-type story where he's got like a fever, he feels like death, goes out and delivers a great basketball game, and then goes back and passes out.

I don't think it's because people feel that they have to. I just think it’s because there's no real alternative. I would never try to second guess why Bob did anything or thought anything, but my impression was it wasn't as if he got there and he goes, "Okay, I may be sick but now I'm going to do it." No, I think he just walked down on that stage and that's what he did.

Once I asked him, I think it was in Florida just before the end of the tour, "All this, how can you do it?" He said, "Billy, that's what I do." It was beautiful that way, it was so unpretentious and totally unguarded. "That's what I do." Those were his words. "That's what I do."

We started talking about the beginning of the tour and I wanted to ask you just about the end of it, anything you remember in particular about the last show or shows or just how it ended after this long year on the road?

There has been a very tragic occurrence, I think in Louisiana, and that was Jimmy Hungerford, who was one of our riggers, went up to take down the sound system and he did not have a safety belt on and he fell to his death.

Oh god. Did that cast a pall or a black cloud over the end of the tour? It looks like that was right near the end of the run.

Yes. It was shocking. It wasn't what I would have hoped for at the end of the tour. We knew this kid. He was a nice kid. He fell for like 90 feet. He died in [crew member] Roger Danchick's arms. It was just terrible.

By the way, another example of Bob's generosity was, Jimmy was from Tennessee or someplace around there. He was a Southern kid and his parents were having a funeral straight off. A lot of us, I think Ian and me and David and Steven, we all went to the funeral. Bob gave us the jet. That must have cost him $15,000, $20,000 to do that if not more. He just said, "You guys go to that funeral and you take the jet."

We weren't that close with the crew, but the thing is, Bob was in it with everybody. It wasn't like he went first class, and we went with coach. Everywhere, it was just a band. That's the way it was set up. He did not remove himself from the other people on the tour. Out for dinner, he would sit next to the bus drivers, as well as sit next to management. That's just the way he was. He was not a snob, he was not fond of himself, he was not in any way acting better than anybody. He was just being a regular guy.

Was that unfortunately how it ended, and then you all went your separate ways, after that last show?

Yes, Miami was the last show, if I remember correctly. I flew back to New York and visited my mom and dad, and everybody went home.

I know the “Legionnaire's Disease” story is one interaction. Did you have any other interactions with Dylan after that, or was that closing a chapter?

He came to Copenhagen to play in the '80s, I think it was. I met up with him, and we talked a little bit, then went our separate ways.

He invited me to a show in Odense with my son. Got us tickets and backstage and everything, but the people who were doing the security were really very unpleasant. They whisked him out of there before I could even get a chance to say hello. I got a message from Jeff that Bob had sent love. He said Bob would really like to see you, but I never got a chance to see him that time. I think that after John Lennon was shot, things changed in terms of getting close to anybody, even if they know you.

Thanks so much to Billy Cross for taking the time to chat! Here’s a show from the European run, Billy’s favorite part of the year, with some different songs than ‘At Budokan’:

1978-06-26, Westfalenhalle, Dortmund, West Germany

Update June 2023:

Buy my book Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members, containing this interview and dozens more, now!

ICYMI

One Random Song: "The Sound of Silence," Anaheim 1999 [subscribers only]

1999-06-20, Arrowhead Pond of Anaheim, Anaheim, CA, USAFranz Nicolay on Dylan and "the dignified absurdity of show business" [free]

The Hold Steady pianist and author discusses the Dylan shows he's seenThe Dylan Concert Album That Coulda, Shoulda Been [subscribers only]

1964-05-17, Royal Festival Hall, London, EnglandNever-Seen Rolling Thunder '76 Photos [subscribers only]

1976-05-19, Henry Levitt Arena, Wichita, KSAn Oral History of Dylan's 'Hard Rain' Concert [free]

1976-05-23, Hughes Stadium, Fort Collins, COThe Real Royal Albert Hall [subscribers only]

1966-05-27, Royal Albert Hall, London, England

incredible interview; such an articulate, well-spoken, cool guy… among the best, most interesting interviews i’ve read here👍 really enjoy your work and passion for detail and the fascinating subject at hand.

Thank you for this. I don't read many Dylan articles which offer anything new and this was fresh. I saw him in Mobile, Alabama in the latter part of the tour and the show was phenomenal. When Budokan came out I was delighted, but then somewhat disappointed after I'd listened. The arrangements had shifted and evolved and were much better by the end of the tour. I still enjoy the album, but have always wished for a follow-up of a later show.